That whole routine of pushing the youngster out of the nest and into the big wide world to make their own mark must take on an extra dimension when you’re in the same domain.

Imagine then a Japanese father raised during the war and brought up with discipline and austerity, a son the product of the 1960s and a free-thinking artist. That they had disagreements is not such a surprise, but they have something quite wonderful in common – they are both influential car designers, and the son is on the verge of continuing the legacy of an often disapproving father.

Matasaburo Maeda is the long-retired designer of the original Mazda RX-7, the now classic rotary-engined sports car that holds mythical status in the world of Mazda. His son is Ikuo Maeda, who has risen to be the company’s head of design and who has long harboured a dream to revive the RX-7. Not because of his father, but because he is a car enthusiast.

It says much as the father-son relationship that Ikuo went off to design college and bought as his first car an RX-7 – without even realising his father had created it while the young man was still living at home. He bought it simply because he liked the shape and it was fast. It’s no coincidence that Ikuo’s nickname is Speedy.

Similarly, when Ikuo was chosen to design the so-called ‘successor’ to the RX-7, his father only found out three months before the four-door RX-8 went on sale in 2003.

I had the pleasure of sharing dinner with Ikuo during the launch of his Mazda 2 in 2007 and he revealed that he and his famous father had opposite views on car styling and often argued. “We decided early on not to talk about styling, otherwise there would be arguments,” he explained sadly. “We still don’t talk about it.”

Ikuo describes his father’s design philosophy as “quiet and sleek” while his is “dynamic and full of movement; he pursues forms that are stable, whereas mine are all about instability and fluidity”. The young man – I can’t believe he’s now 56 – is a bit of a rebel still, a racer at heart, though now a senior executive of a highly respected car company.

Although Ikuo professed eight years ago to be unconcerned about the lack of parental approval, in a more reflective moment he revealed a desire to design a new-generation RX-7, with two seats and a rotary engine. He said he hoped his father would like it. If he didn’t have a tear in his eye, I certainly did.

I didn’t see Ikuo again until a few years ago in a quiet corner of the Paris motor show, where he charmingly pretended to remember me. I reminded him of our conversation and he said of the RX-7: “It is still my dream. When we make the money, I will be able to spend the money.”

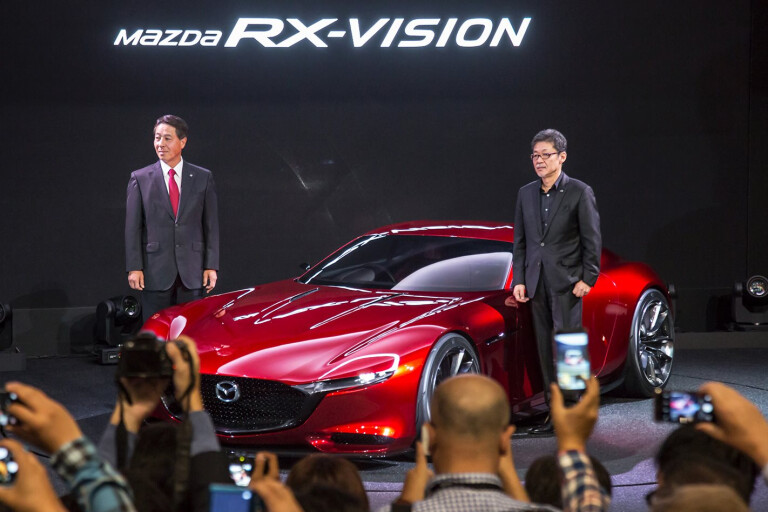

So it was with considerable delight that I saw the RX-Vision revealed at the Tokyo motor show in November. Ikuo stood alongside it on the stand, looking deservedly pleased with what will surely be the realisation of his long-held dream.

I hope his father is proud.

WORLDS APART

MATASABURO Maeda looks like any other retired Japanese businessman headed for the golf course, but in the world of Mazda the former design chief is revered.

Now 82, Matasaburo recalls that his work was arduous, and that he never took it home with him. That would explain how little his son knew of his work, even though he recalls people named Giugiaro and Bertone visiting the house. But as a youngster Ikuo had little interest in cars; he was more interested in architecture.

Ikuo has made Mazda a style-driven brand. His design philosophy is opposed to his father’s, which is rooted in engineering, but he’s impressed his dad became a car designer when this job description didn’t exist in Japan. “He was ahead of his time,” Ikuo concedes.

David Hassall is a veteran motoring writer and is sub-editor of Wheels.

This article was originally published in Wheels March 2016.

COMMENTS