"Lion!” No matter how soundly you’re sleeping it’s the one word guaranteed to raise you immediately from slumber in the African bush.

This feature was originally published in 4x4 Australia’s June 2012 issue

I unzipped the rooftop tent’s gauze and stuck my head out (not a good thing to do, by the way, when camping on the ground because a prowling predator might bite it off). “Where?” I hissed from the relative safety of the roof of my Defender.

My wife nuzzled under the doona beside me, two eyes blinking comically through the little slit she’d left as she peered out, also hoping to spot the cat. “Just crossed the stream. Two lionesses. Hunting.” My friend Riaan, from Johannesburg, was tracking the cats with his binoculars, which were remarkably effective under the light of the full moon. Damn. Missed them.

My wife nuzzled under the doona beside me, two eyes blinking comically through the little slit she’d left as she peered out, also hoping to spot the cat. “Just crossed the stream. Two lionesses. Hunting.” My friend Riaan, from Johannesburg, was tracking the cats with his binoculars, which were remarkably effective under the light of the full moon. Damn. Missed them.

Counting animals in Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park can be as exciting as it is frustrating. But make no mistake: despite the terrible economic, political and social problems that have devastated the country in recent years, there is still plenty of wildlife to be found there.

The annual Hwange Game Census (or game count as it’s more commonly known), organised by Wildlife and Environment Zimbabwe (WEZ), attracts volunteer counters from around the world, including regular contingents of Australians, like ourselves. The count takes place over a 24-hour period timed to coincide with the last full moon of the southern African dry season (usually in late September or early October).

The theory is that, as the ground water evaporates at the end of winter, animals will congregate around the remaining water sources. As all mammals need to drink at least once every 24 hours, the idea is that most can be recorded by watchers placed at strategic waterholes and streams.

The count is co-ordinated out of Hwange’s three main rest camps: Main Camp, Sinamatella and Robins. Our team of friends from Australia and South Africa was based out of Robins Camp, in the north-west of the park only 30km east of the Botswana border, and about 100km south of the famous Victoria Falls.

After receiving our safety brief (stay in your cars at night time) over a braai (translation: barbecue) we split ourselves into two groups in order to cover our assigned water points.

Team Land Rover – Nicola and me in our 1997 Land Rover Defender 300 Tdi and Riaan and Annelien and their two kids, Leyla (eight) and Adriaan (six) in their 1994 V8 Defender 110 – head south out of the camp the next morning to cover the Little Toms waterhole, about 10km from camp.

Heading a few kays further down the track to the Big Toms waterhole are the Toyotas – Brett and Claire Martin from Mansfield, Victoria, in a rented Toyota HiLux dual-cab, and Dewald and Bettie Botha from South Africa, in a LandCruiser TroopCarrier with an interesting connection to Australia.

Dewald, an engineer, and Bettie lived in Western Australia for a couple of years while he oversaw the construction of a nickel processing plant. While in Australia they bought the Troopie, had it converted into a camper, and explored a good chunk of Australia in their spare time. They shipped the Cruiser and themselves back to South Africa at the end of the contract.

Brett, who manages Martins Garage, a Nissan dealership, had rented his HiLux – fully kitted with rooftop tent, fridge and camping gear – from Hemingway’s Vehicle Hire, across the border in Livingstone, on the Zambian side of Victoria Falls. It was no problem to bring the vehicle into Zimbabwe, where local car-hire options were limited and expensive.

Hwange, Zimbabwe’s flagship national park, has suffered from underfunding and a lack of visitors in recent years, but despite that the roads are generally in good condition. A two-wheel drive with high ground clearance could cover most of the park in the dry season, but a 4X4 is recommended, especially in the wet (October to April).

The long winter sun had sucked the last of the moisture out of the air and long yellow grass swayed in parched vleis (floodplains) between bush dried the colour of khaki and grey. On our drive to the waterholes we passed a big herd of at least 300 Cape buffalo. Despite their seemingly cow-like passivity, these animals are known as Black Death for the danger they can pose if you disturb one on foot.

Big Toms and Little Toms are waterholes sunk when this part of Hwange was a cattle farm owned by Herbert Robins (who, incidentally, was born in Australia before moving to Rhodesia – as Zimbabwe was then known). On his death, Robins bequeathed his farm to the national park.

Poaching unfortunately occurs in every African national park, but parts of Zimbabwe have been particularly hard hit. Rhinos – whose horns are used in illegal traditional Chinese medicine – are being killed at an alarming rate.

The zebra and kudu antelope drinking at Little Toms scattered into the bush when we arrived. However, within half an hour the animals were back, eyeing us nervously and perhaps just startled by the unusual appearance of humans.

Our count began at midday and the day was Africa-hot, with temperatures hitting the high thirties. However, at Little and Big Toms we were lucky to have thatch-roofed viewing hides to count from. Our job was to record the different types of species, the sex of the animals if possible, whether they were adult or young, and make notes of anything unusual, such as injury or poor condition.

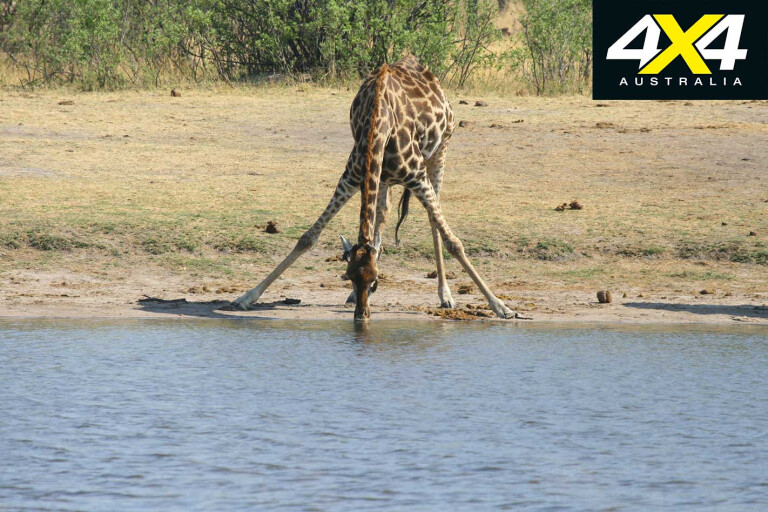

A pompous pair of warthogs and a gangly giraffe came down to the water to drink, but much of the game we noticed was drinking about 100m upstream from the main waterhole. We suspected there might be a sweet spring up there.

As the sun lost its sting we decided to leave the hide for the night and reposition ourselves in the bush overlooking the stretch of creek where most of the game had been drinking. We loaded the Land Rovers (and the only pair of kids I know in the world who could sit quietly in the back of a truck colouring in for 24 hours) and moved camp.

The game count is the only time tourists can be out in the national park overnight unsupervised. It’s also the only time guests can drive off-road, and we picked our way carefully around anthills, aardvark holes and trees whittled down to toothpicks by passing elephants.

Hwange is known as the Kingdom of the Elephants, and for good reason. Tens of thousands of these giant beasts live in the park or pass through here on their way to and from neighbouring Botswana in search of food and water. In Hwange the elephants drink at night, leaving the shade of the bush for the lure of water in the cooler hours and as soon as the sun set an endless night-time elephant parade began.

Riaan, Annelien, Nicola and I divided the night into two, tossed a coin, and they picked the first shift.

It was about 11pm when Riaan hissed into the darkness that he’d seen two lionesses cross the stream, not 30m from where we had parked the Landies. Nicola and I missed them, but when we took over at midnight there was plenty of night noise out in the bush to keep us wide awake. We sipped coffee and packet soup from flasks as hyenas whooped and some startled zebra brayed.

The last few hours before dawn dragged, as even the elephant extravaganza slowed, but the whole exercise was worth it to see the sun come up over Africa. We’d strung shade cloth between the two Defenders to make an improvised hide and as the 24 hours drew to a close we treated ourselves to bacon and eggs in the bush.

As Nicola and I led the way out of the bush and re-joined the dirt road back to Robins, a muscular, wild-eyed lioness broke from the scrub and took about half a dozen menacing strides towards us.

Heart pounding and expletives flying we skidded to a halt. There in the bush was the snarling lioness and her sister, and the remains of a zebra, whose last mortal calls we’d heard in the night, from less than 100m behind our encampment.

As the bigger lioness dragged her striped kill away from the road and under the shade of a tree, we saw why she’d acted so protectively. With the girls was a cub – new life and a ray of hope for a small pride of lions in a big, troubled country.

Count me in

First run in 1972, the Hwange game count is the longest continuous-running game census in southern Africa.

It provides the Zimbabwean national parks authorities and wildlife researchers with crucial data on wildlife diversity and numbers.

There were 38,451 animals recorded in the 2011 census, covering a total of 46 different species.

The majority of animals counted – 61.5 percent or 23,569 individuals – were elephants. While declines in the numbers of several species were noted, this was the highest number of elephants ever counted.

Cape buffalo were the next most numerous animal, with 3433 recorded.

Is Zimbabwe safe?

Zimbabwe’s wildlife, like its people, has suffered under decades of misrule and economic mismanagement. President Robert Mugabe’s disastrous policy of confiscating and redistributing white-owned farms crippled the economy and the local currency spiralled into oblivion after years of rampant inflation.

Today, however, the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) has a hard-won place in a coalition government and the country has swapped its worthless dollar for the American greenback.

All is far from perfect in Zimbabwe, but the measure of stability brought by the change in currency means that fuel and most goods can be readily bought.

While violence and intimidation of the MDC and its supporters is, sadly, a feature of local elections, this does not manifest itself in the form of animosity or danger for tourists. By African standards its crime rate is low and its people are welcoming.

Out of Africa

Tony Park is a freelance journalist and the author of eight novels set in southern Africa, and three biographies.

Tony grew up in the western suburbs of Sydney and worked as a newspaper reporter and in public relations before quitting full-time work to follow his mid-life crisis dream of writing fiction.

A short holiday to Africa in 1995 with wife, Nicola, turned his life around and gave him the material he needed to write his first novel, Far Horizon, a thriller set on an overland tour trough South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Zambia.

Having been bitten by the Africa bug, Tony and Nicola have been back to the continent every year since and now spend half their lives in Australia and the other half in the African bush where Tony researches and writes a book a year.

A 4X4 enthusiast and diehard Land Rover tragic, Tony soon worked out that it made more sense to buy and garage a vehicle in Africa, rather than blow money on renting one every year when he returned.

These days he owns a 1997 300 Tdi Defender hardtop kitted for long-range touring and stored with friends in Johannesburg between trips.

He and Nicola have travelled extensively throughout South Africa, Namibia, Zambia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Malawi and Mozambique. They have also visited Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda and Uganda on research and writing assignments.

His novels are thrillers, mostly set in contemporary Africa. They confront the problems facing the continent – crime, corruption, poverty and poaching – and also celebrate Africa’s wide-open spaces and huge array of majestic wildlife.

In order of writing, his books are: Far Horizon, Zambezi, African Sky, Safari, Silent Predator, Ivory, The Delta and African Dawn. His ninth novel, Dark Heart, set in Rwanda, is due for release in November 2012. He is also the co-author of three non- fiction biographies: Part of the Pride (with Kevin Richardson); War Dogs (with Shane Bryant); and The Grey Man (with John Curtis).

Tony is also a Major in the Australian Army Reserve and served as a public affairs officer in Afghanistan in 2002.

He lists his four great loves in life as his wife, Africa, beer and Land Rovers – order depending on the circumstances.

You live half your life in Africa. Why?

Tony: My wife, Nicola, and I visited southern Africa on a short holiday in 1995 and fell in love with the continent, especially its wildlife. We now spend six months of every year there, where I research and write my novels.

What sort of vehicle do you drive?

Tony: I own a 1997 Land Rover Defender 300 Tdi hardtop called Broomas (named after a polar bear – it’s a long story), which lives with friends in Johannesburg when I’m in Australia.

Scariest moment in Africa?

Tony: Having two hungry lionesses circle our tiny dome tent in Mana Pools National Park in Zimbabwe’s Zambezi valley. My life flashed before my eyes.

Are your novels based on real-life experiences?

Tony: My novels are thrillers, set in contemporary southern Africa, so they deal with the real-life problems of the continent, such as crime, corruption, and poaching, but I also try to show the beauty of the continent.

The latest, African Dawn, deals with the tumultuous recent history of Zimbabwe including the invasion of white-owned farms and the plight of the endangered Black Rhino. There is also a strong message of hope in the book. And plenty of 4X4s and sex.

COMMENTS