AWAY from the bright lights of Toyota’s product presentation hall, around the corner from its impressive glass-fronted national headquarters and in a small conference room on the ground floor of the southern region office, Toyota Australia’s top brass are assembling to front motoring media and break the company’s recent silence.

Since the Japanese car maker announced it would cease manufacturing on Australian soil nearly four years ago, precious little extra information has been shared outside Toyota’s walls, and the company has remained tight-lipped until today – less than a week out from the actual day when the stop switch will be thrown at its Altona plant, October 3, 2017.

Toyota Australia’s outgoing president David Buttner leads the proceedings flanked by chairman Max Yasuda and sales and marketing executive director Tony Cramb, both of whom will also leave the Toyota fold by the end of the year.

Buttner opens with a serious tone as he explains the company’s target of preparing and retraining each employee to maximise their chances of reemployment, and remains austere as he lays out the plan to relocate the company’s Sydney headquarters into the Melbourne site.

The reason for Toyota’s code of silence in the lead up to the factory closure, says Buttner, has been out of respect for its loyal employees and to allow the company to completely focus on protecting the staff that are facing the cold realities of redundancy.

There is no doubt that Toyota has pumped huge resources into mitigating the hardship felt by its parting employees, but the lack of communication will have also avoided some tough questions.

But as the conversation moves to the future Buttner’s mood lightens.

Perhaps he is confident that Toyota will indeed continue to dominate the Australian new car market and that the future really is a bright one after local production finishes, or perhaps he is feeling a weight lifted from his shoulders after 41 years in a tumultuous automotive industry. No one really knows what the future holds for the Big T as a full-line importer.

“Our attitude is that there is always a better way and the day you stop thinking that there is a better way is the day you plateau or fall off the curve,” Buttner says.

The 2600 employees that went to work for the final time in Altona this week would no doubt agree with Buttner’s sentiment, but struggle to believe that closing the factory after 54 years of Australian manufacturing was indeed the better way.

More than 30 minutes have passed and president Yasuda has so far remained silent, hands folded, nodding occasionally in agreement with his colleagues, but when asked how he felt about snuffing the lights at Altona for good, he leans forward and engages the room.

“On the day of the announcement it was a sad day,” he said. “It was a very, very difficult decision to end manufacturing but it’s done. Right after the announcement, I thought to myself, we have four more years to run the business and make a good transition for our people.

“Myself, I don’t know how they keep their motivation so high and keep this performance going through to the end. It’s amazing.

“On the day, the 3rd of October, this is going to be quite an emotional day for all of us.”

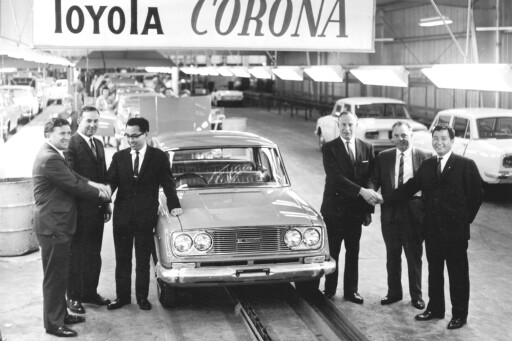

Australia will forever have a special tie to Toyota and was the first country outside of Japan to assemble Toyotas for its own market, but Yasuda explains that the local factory now had another world first.

“Once Toyota is in, there’s no word of pulling out. That’s a fundamental concept of Toyota. This was the first time we made this decision to pull out on such a big scale.”

But despite the less admirable claim to its name, lessons would be learned by the shut down and Yasuda said the company would never let it happen again.

“In that sense, this is unique and one thing that we discussed with TMC when we made the decision was ‘let’s review how it happened and why we had to make these kind of decisions and make sure this never happens again in the future’.

“We have so many factories around the world which are struggling, but learning from what happened in Australia we want to make sure it will never happen again. The basic concept of never pulling out is still there.”

Matthew Callachor completes the Toyota panel of four and remains the most resolute throughout the one hour briefing. It’s Callachor that will guide Toyota Australia through perhaps its most challenging years yet when he takes over from Buttner at the end of the year.

Like every one of the four executives, Callachor’s stack of papers remains untouched on the desk. His vision of the future is well rehearsed and needs no notes for prompt.

No doubt the factors and variables that lead to Toyota closing its facility in Melbourne’s West will be digested over many years to come. Some cite the cost of local manufacturing, others blame the profit margins in a model that struggled to compete against Australia’s demand for SUVs, and there is no doubt that just one car maker was insufficient to support the supplier network after Ford and Holden pulled out.

What happens after lights-out at Toyota’s Australian factory?

Whatever the reasons, Cramb confirmed that high-level decisions had led to the factory shut down, and the company’s culture – a critical component of pride in any Japanese company - was ultimately to blame.

“It’s deeply, deeply cultural and a sign of failure of management. That’s the way we look at it ourselves. We failed the society, we failed the community and we failed our people”.

The end of local car manufacturing and the reality that the Australian automotive industry has permanently changed will forever be embodied by an Australian car with a Japanese name, and as the dust begins to settle on the robots that once built cars with the same stoicism as their human counterparts, the realisation that we are losing something great is only just starting to dawn for many.

COMMENTS