The promise of autonomous cars has no doubt been an exciting and intoxicating one for technophiles everywhere, not to mention those who see driving as a chore that must be endured, rather than enjoyed.

There’s no shortage of autonomy evangelists – Tesla CEO Elon Musk is a famous example, Ford reckons it will have its first truly self-driving car ready by 2021 and BMW and Mercedes have similar timelines – while ridesharing companies and Silicon Valley tech giants like Uber and Google are also bullish on fully-autonomous vehicles.

And why wouldn’t they be? Without a driver taking a cut of fares, profit margins for those businesses would explode, while also giving the public cheaper rides and potentially freeing them from the financial burden of owning a car.

But according to one of the world’s biggest manufacturers of the advanced sensors that make autonomous cars possible, the utopian vision of completely hands-off, point-to-point driving is highly unlikely for the foreseeable.

Speaking at the 2019 Continental TechShow in Hanover this month company CEO Dr. Elmar Degenhart said advanced self-driving cars that can pilot themselves with zero intervention from the driver will only make up a miniscule fraction of the global vehicle fleet by 2030. And even then, they’ll likely mostly be bought up by the aforementioned ridesharing companies.

And it all comes down to cost.

“A new car buyer is willing to spend more for safety and greater convenience,” Dr. Degenhart said.

“At present, as much as €3,000 (AU$4860) more. Those were the findings of our own studies. Systems for highly automated and autonomous driving are substantially more expensive. If they cost much more than €3,000, then the interest of the buyer wanes.”

According to Continental, the cost of equipping a car with a ‘level 2’ or L2 autonomous driving capability, which covers features like active cruise control and lane keep assist and still requires the driver to pay attention and keep at least one hand on the wheel, is just over AU$4000 per vehicle.

Stepping up to a genuine L3 autonomous capability, which allows the driver to go hands-off and safely take their eyes off the road, requires a far bigger spend of around $16,000 per vehicle.

Why? The sensors required to enable a higher level of self-driving are simply more expensive and more numerous, with an L3 car requiring some 30 individual sensor modules versus an L2 car’s 18. While that cost will likely creep down over time, the premium is still a hefty sum for the majority of car buyers.

Though most may like the idea of a car that can drive itself in limited circumstances (L3 is only expected to work well in slow traffic or highway environments), the sheer cost of that capability will likely slow its uptake.

“Our industry is currently putting a huge amount of money into driverless driving,” said Degenhart.

“In many cases, we feel that it is too early, because we are not expecting to see substantial growth in this field for another ten years. An exception is the business with robotaxis, which are driverless taxis. They will probably get started earlier.”

But even with the likes of Uber and Lyft buying fully-autonomous vehicles (either L4 or L5) for their proposed fleets of robotic taxis, Continental sees cars with that level of capability accounting for a minor percentage of overall new car sales in the future.

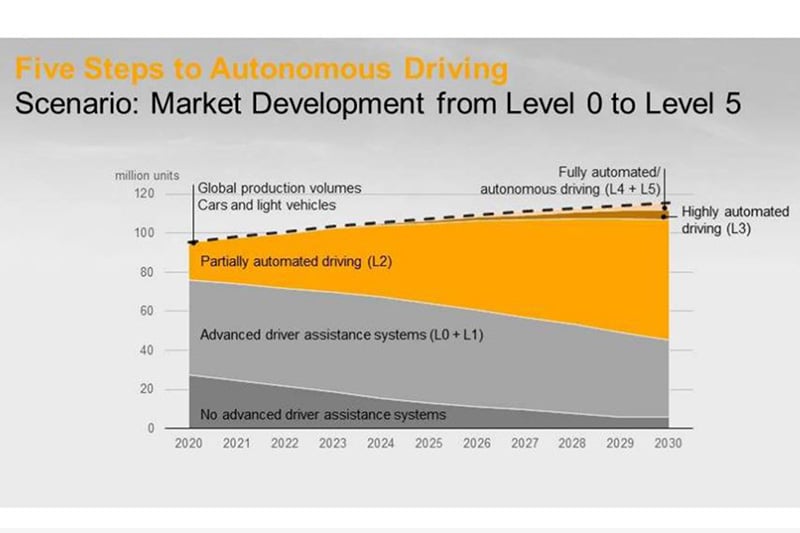

A slide shown by Degenhart at the Continental TechShow in Hanover showed the expected uptake of autonomous cars over the next 11 years, and its prognosis for self-driving tech isn’t good. By the end of 2040, the estimated amount of cars with at least an L3 autonomous capability only accounts for a thin sliver of overall global sales.

The bulk of sales are instead expected to be taken up by cars with a similar level of autonomy to what’s available today – L2. Beyond the ability to guide themselves down highways without much intervention (but constant monitoring), those L2 cars are far from the fully self-driving ideal that many people believe will become widespread by the end of next decade.

L1 cars will account for the majority of the balance, though with L1 covering systems like autonomous emergency braking and blind spot monitoring, it will only be a few short years before L1 cars become the bare minimum in developed countries like Australia.

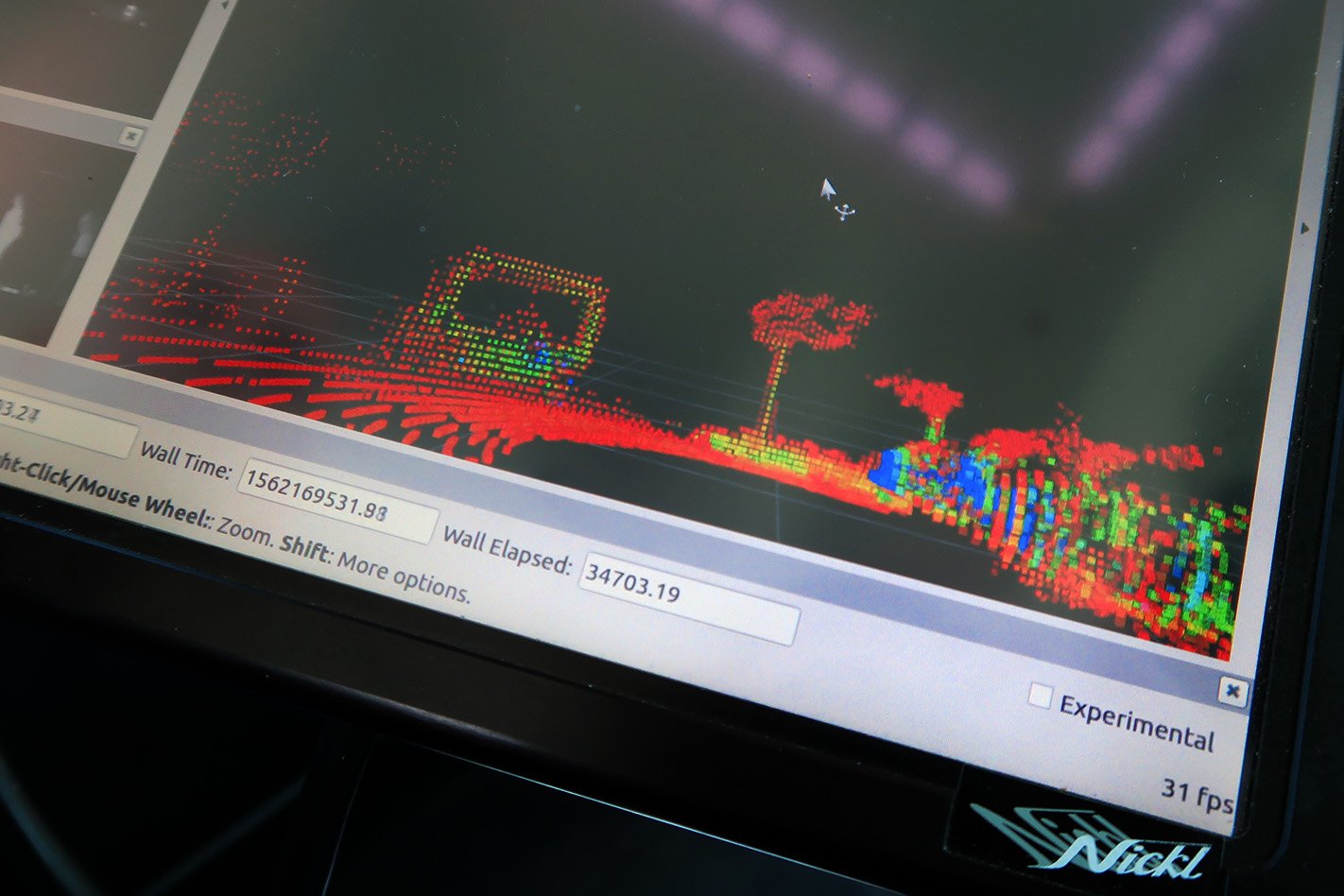

The challenges of making fully self-driving cars a reality became evident when we hitched a ride in one of Continental’s autonomous demonstration vehicles, the Continental Urban moBility Experience.

Equipped with a range of radar, lidar, ultrasonic and optical sensors, the CUbE is able to pilot itself along a regular road and react to obstacles like pedestrians and other vehicles by either stopping or moving out of the way… but it is glacially slow.

Other companies are forging ahead with integrating the tech into cars that move at a far more realistic speed, but questions remain about the ability of computers to correctly identify and react to unexpected threats at those kinds of velocities.

A pedestrian has already been killed by an experimental autonomous vehicle operated by Uber, and debate rages about how much authority should be given to a car’s self-driving software in the first place.

Even Google’s self-driving development division, Waymo, says a true L5 autonomous car will never be realised.

“We know from our own surveys that acceptance for autonomous driving today – and we’re not talking about robotaxis – is relatively low. It’s somewhere around the 30-35 percent mark, depending on the market. It’s highest in China, interestingly enough”.

“That means, it will take time.”

And while Silicon Valley giants might make it seem like a world of on-call autonomous taxis is just a few years away, Degenhart says the ‘move fast and break stuff’ culture of that corner of the tech world is incompatible with the realities of the carmaking business.

“In Silicon Valley, the adage is: Better done than perfect. In contrast, in the automotive industry it is: Better perfect than done. Because only perfect is safe.”