History is littered with the skeletons and emaciated frames of companies that failed to diversify, staggered to the brink of extinction and, in many cases, died.

Kodak, Blackberry, Blockbuster Video and, perhaps the most obvious and recent example in the automotive world; Holden. None could weather the storm of shifting consumer demand.

But the same fickle and indiscriminate set of circumstances that can undo an organisation applies to almost any company and in any industry if the writing on the wall is ignored for too long – even the petrochemical sphere and the oil giants that occupy it.

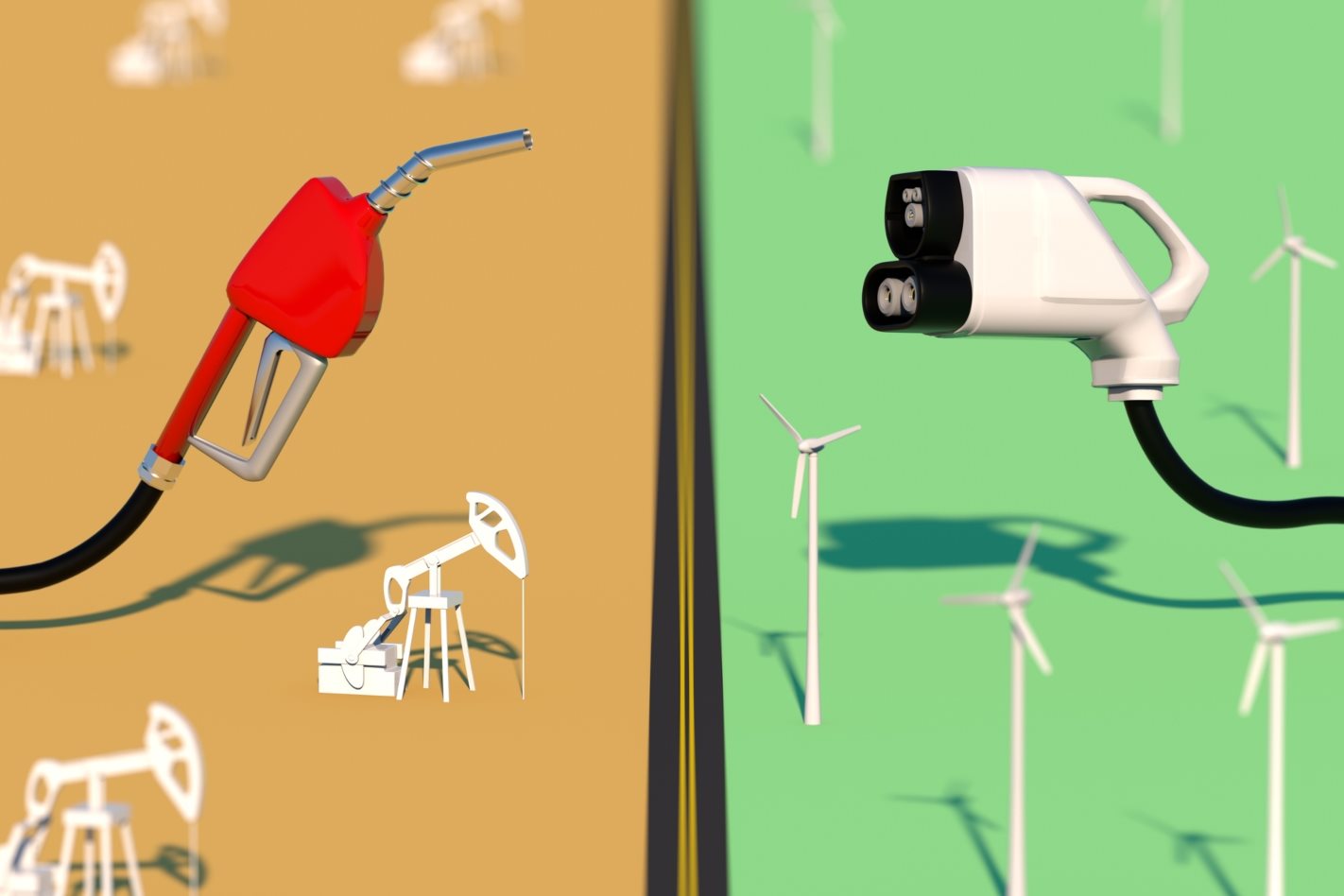

It might seem ironic or paradoxical, but in a bid to survive the unstoppable transition away from fossil-fuelled transport and into renewables, oil companies are investing in electrification and EVs.

There once was a time when the various oil giants were actively trying to crush the electric vehicle industry and succeeding – indeed there are some theories that suggest they still are.

Either way, whether it be a PR stunt, simple self-preservation, or a balance of both, oil companies are looking for the so-called ‘new fuels’ and green gold.

What are oil companies doing about electric vehicles?

If you can’t dig electricity out of the ground and the business of generation is tightly in the hands of the power companies*, how can the incumbent oil giants muscle onto the EV scene? The answer is utilities and a charging network.

From a historical and legacy perspective, fuel companies are the obvious champions of public charging infrastructure.

With an existing network of refilling stations, installing or repurposing for electric outlets is a smaller step than creating a network from scratch, and their respective branding and identity is already associated with somewhere to go when the ‘tank’ is getting low.

But unlike petrol and diesel cars, EVs can be topped up at home and probably will be a majority of the time so there won’t be a one-for-one filling station swap when an owner retires their combustion car for an EV.

That’s why the oil companies need to do more than simply switch pumps for power points to get a comparable slice of the EV action.

*Many of the big oil companies have interests in power generation including renewable energy.

Royal Dutch Shell

The iconic scallop shell is the most active oil company in renewable energy with more than US$1bn (A$1.4bn) already committed to clean power including ‘new fuels’.

A chunk of the cash was used to acquire Greenlots – a Californian startup with global projects developing charge networks and services as well as collaborations with BMW.

It also bought German battery company Sonnen, one of Europe’s largest EV charging enterprises New Motion, while its acquisition of First Utility has enabled the company to now act as an energy retailer in the UK.

And while battery electric vehicles are garnering the lion’s share of the alternative energy attention, Shell is investing in the emerging potential of hydrogen FCEVs with a growing network of hydrogen refilling stations in Germany.

The British-Dutch giant is also a major sponsor of the Nissan Formula E racing team and says it has a vision to improve the EV driving experience.

“Shell has the unique ability to use its technology and marketing expertise to develop more and cleaner mobility solutions that will serve the growing number of EV customers both on and beyond the forecourt,” it says.

It’s worth noting that Shell has extensive resources in energy generation around the world including wind and solar farms.

Total

France’s big oil hitter has some significant EV investments in its home continent. Partnering with PSA, the company is building an EV battery factory, has 20,000 chargers planned for Amsterdam, and has solar and e-mobility projects ongoing in China.

Since 2002 Total has had a hydrogen presence in Germany, where it commissioned its first refuelling station and the partnership with H2 has continued with more hydrogen infrastructure padding out the alternative energy picture.

Total also closed two significant deals in 2018 to add EV assets to its name. The acquisition of G2mobiliuty snared the company a major charging solutions outfit, while the purchase of Direct Energie turned Total into an electricity retailer in Europe.

In September 2020 it further expanded its charging reach by acquiring Source London, the English capital’s largest charging network, which has more than 1600 on-street charge points across the city.

Finding ways to sell electricity is an oil giant trend you can expect to see continuing.

Sinopec

Who? While Saudi Arabian and American oil companies get a lot of the press (both good and bad) in mainstream media, a Chinese company is the biggest global player in terms of revenue.

Otherwise known as China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation, Sinopec is the world’s largest oil company but is yet to match the EV efforts of some smaller organisations.

The group has invested in battery swap technology and infrastructure in its native China, but the company’s main focus is hydrogen and intends to become the nation’s hydrogen leader.

The relative environmental apathy is understandable given China’s green targets that lag many other parts of the world – where power and fuel companies have more of a presence in EV and renewable industries.

Chevron

The North American players have not been as swift to pounce on the EV cause but there are a handful of incentives paving the way for more action.

Chevron Technology Ventures has made a strategic investment in Natron – a Californian tech company that’s developing new energy storage solutions using a revolutionary Prussian Blue electrode innovation.

Chevron is also an investor in Chargepoint and has helped the company build the funds to roll out a massive charger network in Europe and the US.

The venture is in direct response to other oil companies supporting or buying charge infrastructure companies. Dominating charge networks is another strategy that will continue to emerge from oil companies.

To date, the company has invested more than US$100m (A$136m) in its Future Energy fund and includes the Solarmine photovoltaic array that powers one of its Californian oil drilling fields as part of the portfolio. There’s another irony there if you want it.

ExxonMobil

Fellow North American energy giant ExxonMobil is also starting to talk about an EV-heavy future.

While it hasn’t yet been as actively involved as some of its rivals, the company has partnered with universities in EV projects and is researching electric transport through its involvement in the Formula E championship with Porsche.

BP

Last year, the British multinational announced it would be increasing its presence in China and its lucrative but challenging EV industry. Partnering with DiDi, BP is rolling out a charge hub network across the nation.

In June 2018, the company announced it had bought the UK’s biggest charging network Chargemaster. The venture resulted in more than 6500 chargers around the UK being repainted in the company’s green and yellow (and a little blue), as well as new chargers added to BP forecourts alongside the more traditional bowsers.

Through its sub-brand Castrol, BP also commissioned a report into global EV adoption and examined where the ‘tipping point’ for electrified vehicles lies.

It’s moves like this along with the use of the term ‘climate change’ by the various companies that suggest a petrochemical leopard can change its spots.

Like Shell, BP is regarded as one of the world’s ‘supermajors’ in oil and has significant interests in renewable energy including biofuels, solar, and ‘smart grid’ technology.

Essential oils

But don’t expect the rise of electric cars to silence the drills and scupper the rigs. Less than half of the oil in each barrel extracted from the earth actually ends up as petrol and diesel.

Aspirin, candles, toothpaste, paints, ice cube trays, soft contact lenses and cinematic film – they all require oil in some form.

And the same applies to the manufacturing of vehicles. The stuff in the tank and the sump isn’t the only oil a combustion-powered car has in it nor EVs for that matter, with petrochemical companies continuing to supply products to vehicle manufacturing most likely forever.

While not all end products need petrochemicals for their composition, part of the process often does. But this too is changing.

More ethical and sustainable materials are being developed all the time including those that depend on petrochemicals less.

For example, the interior of Hyundai’s Nexo contains more than 30kg of materials that are sourced from renewable sources such as bamboo and sugar cane mulch and, while a BMW manufactured in the 1990s had about 15 different plastics in its construction, today’s offerings rely on just four fundamental plastic types.

The simplest explanation

Sceptics and conspiracy theorists might claim oil companies are buying up charging infrastructure startups with the intention of eliminating them from the gene pool to slow or even halt the advance of an EV army, but perhaps the simpler and more plausible theory is the correct one.

After decades of building vast profits from fuelling the world’s transport needs with hydrocarbons, global demand for EVs is forcing the major oil entities to acknowledge electrons are the future and, as the saying goes – if you can’t beat them, join them.