As 2016 unfolded, it became ever more clear that electric vehicles are coming, and that their arrival spells the end of oil as undisputed king of automotive energy sources. But internal combustion will live on even as EVs proliferate. This will be creeping change, not a cataclysmic conflict.

“You need to be able to think two thoughts at the same time,” says Ståle Frydenlund, communications advisor to the Norwegian EV Association. This relatively small outfit played an active role in making Norway a leader in EV adoption. Its influence is now spreading beyond this small Nordic nation’s borders.

What Frydenlund means is obvious when you look at what his homeland is doing. Plug-ins have around a 20 percent share and rising of the new-vehicle market in Norway thanks to the government’s pro-EV policies, even though the Norwegian economy is heavily reliant on North Sea oil and gas production.

“The oil and gas industry will keep going in Norway for many years,” Frydenlund predicts. “Norwegian politicians say it’s not an alternative to let other countries do the oil producing. But, even so, CO² emissions have to come down, and that’s what we’re trying to influence.”

The car industry is beginning to see it the same way. “Everybody knows that we have to go towards emissions-free driving,” Daimler chief Dieter Zetsche told Australian journalists in April. The problem, he noted, is that current customer demand is stronger for AMGs than EVs.

By late September, at the Paris motor show, Zetsche was announcing that Mercedes-Benz plans to produce an entire family of EVs, beginning with an SUV in 2019. There eventually will be “at least seven” EVs wearing the three-pointed star, another senior exec revealed. Also at Paris, Mercedes-AMG boss Tobias Moers confirmed the company would produce an F1-based, petrol-burning hybrid hypercar for the road. The world’s oldest carmaker obviously has room in its headquarters for two thoughts at the same time.

Volkswagen also chose the Paris show to reveal that it, too, intends to make EVs part of its mainstream line-up. Earlier in 2016, the company’s chief executive, Herbert Diess, had led his board on an EV fact-finding mission to Norway.

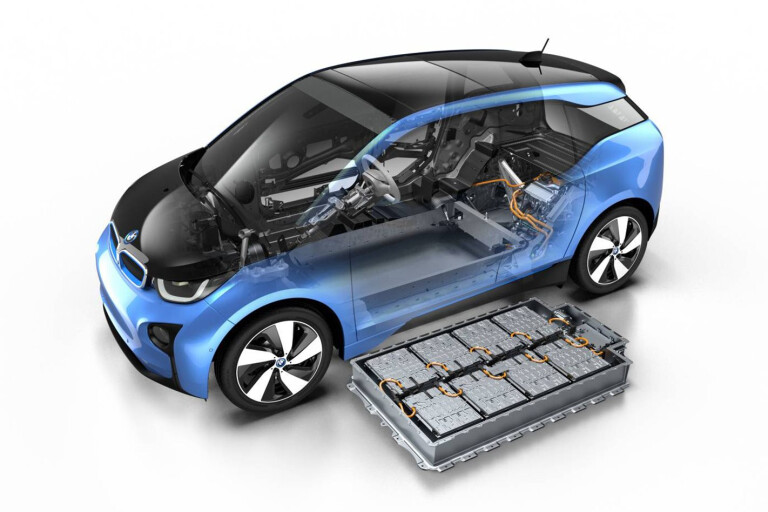

The Paris announcements by Mercedes and VW capped a year full of EV action. GM launched a relatively affordable small hatchback with a driving range to challenge a costly Tesla Model S. To prove the point, Opel drove an Ampera-e, the European version of North America’s Chevrolet Bolt, from London to Paris for the motor show. Tesla began production of its second mainstream model, the Model X SUV, and revealed its first truly mass-market car, the Model 3. Hyundai began production of its Ioniq EV. Renault and Nissan launched updated versions of the Zoe and Leaf EVs with extra range from improved batteries. BMW did likewise with the BMW i3.

Australia lags most of the rest of the advanced world when it comes to EVs. Even so, it’s probably time to start clearing some mental space for the day when this begins to change.

THE HARD CELL

Improved batteries are the key to EVs gaining widespread acceptance, and they’re coming. According to analysis by the International Energy Agency, battery prices have fallen significantly since 2008, at the same time as energy density has risen. What this means is cheaper batteries that can drive an EV further. And Samsung, one of the biggest suppliers of EV batteries, is already promising another big step up in energy density with a new cell it will soon begin producing.

COMMENTS