Rapid manufacturing technology is slowly transforming the way cars are built

Even though it’s been around since the early 1980s, 3D printing technology still has a sci-fi aura surrounding it. The idea that complex three-dimensional objects could be produced by a single machine is still a fairly revolutionary concept, and it’s only recently that such machines have shrunk in size and price to be attainable by private consumers, rather than large companies.

Uptake by the auto industry has also been slow. 3D printing has been useful for making one-off prototype parts for concept cars and test mules for a while now, but the technology is now starting to find applications in production cars as part quality, printing speeds and per-unit cost comes down. Conventional methods of mass-production such as injection-moulding plastic and casting metal will nearly always be more cost effective when dealing with large production volumes, but 3D printing still has plenty of real-world applications in the automotive world. Here are just a few.

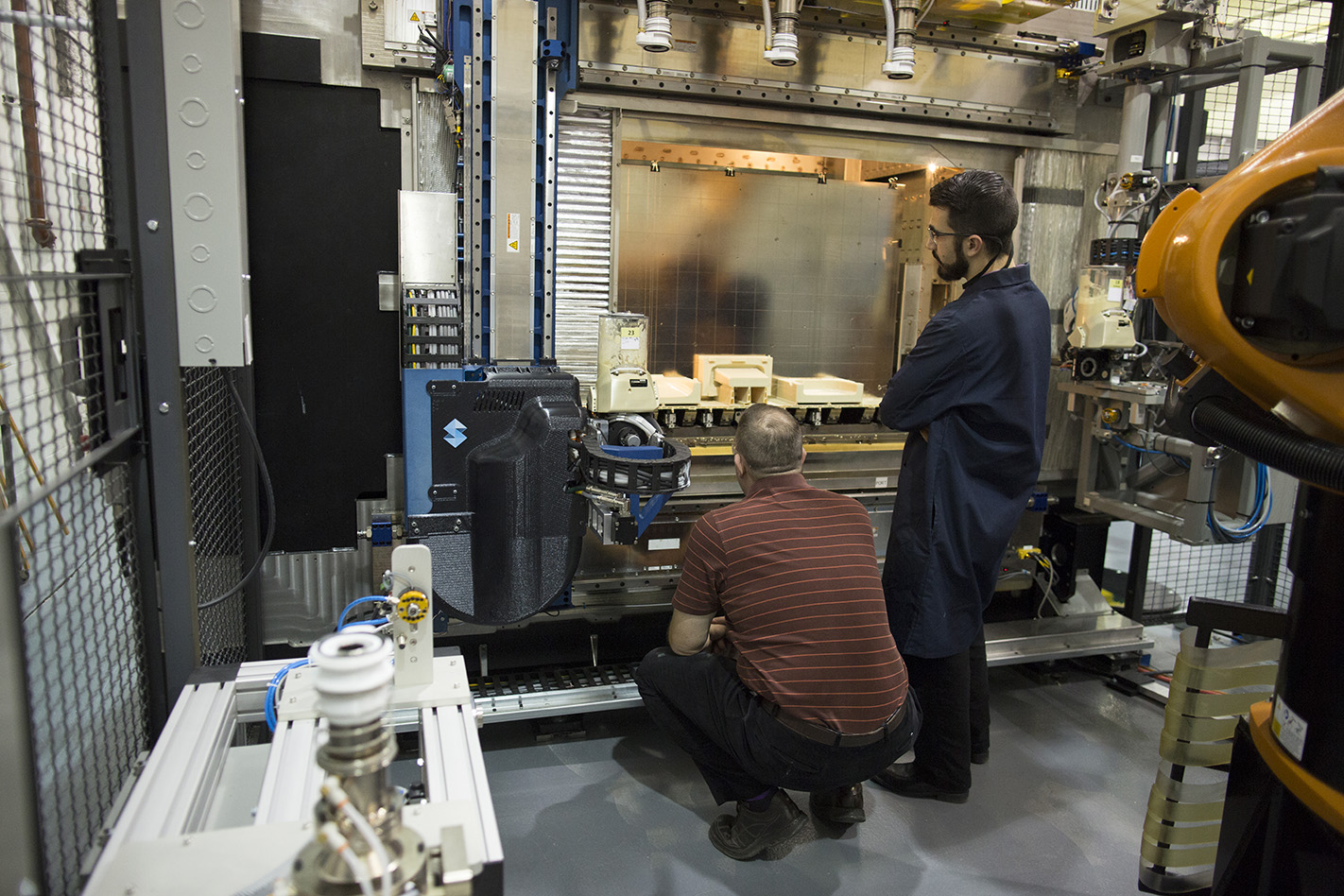

The most useful current application for 3D printing in car manufacturing isn’t the most obvious one, and it doesn’t actually involve 3D printed parts being incorporated into the cars that you buy.

Instead, it’s far more prosaic than that. Manufacturers – among them Ford and BMW – are using 3D-printed jigs and tools to help their line workers assemble vehicles faster, more efficiently and with less risk of injury.

The technology is especially useful for low-run special-edition models that may need unique tools to help install bespoke parts, and with 3D printing being ideally suited to making one-off parts at significantly lower cost than traditional methods including injection moulding or milling, it helps carmakers keep spending in check.

HSV has been using 3D printing since 2010 in order to produce prototype parts. It first tried 3D printing for test bodykits to check fitment and has continued to expand its use to the present day as it converts Camaro and Silverado to right-hand drive.

With much of the behind-the-dash furniture being entirely unique to the locally-converted Chevrolets, the little ducts and brackets that reside in this part of the car are prime candidates for additive manufacturing.

Tooling up for injection moulding each of those parts would be cost prohibitive, but thanks to 3D printing they can all be made by the same machine. It’s a slower process, but if the volume isn’t high then that’s not a big deal.

Speaking of spending, one of the biggest costs involved in being a carmaker is maintaining an inventory of spare parts. Every variant of every model must have enough spare parts available to last at least ten years – the reasonable lifespan of a modern car – and warehousing these things generates significant bills for car companies around the globe.

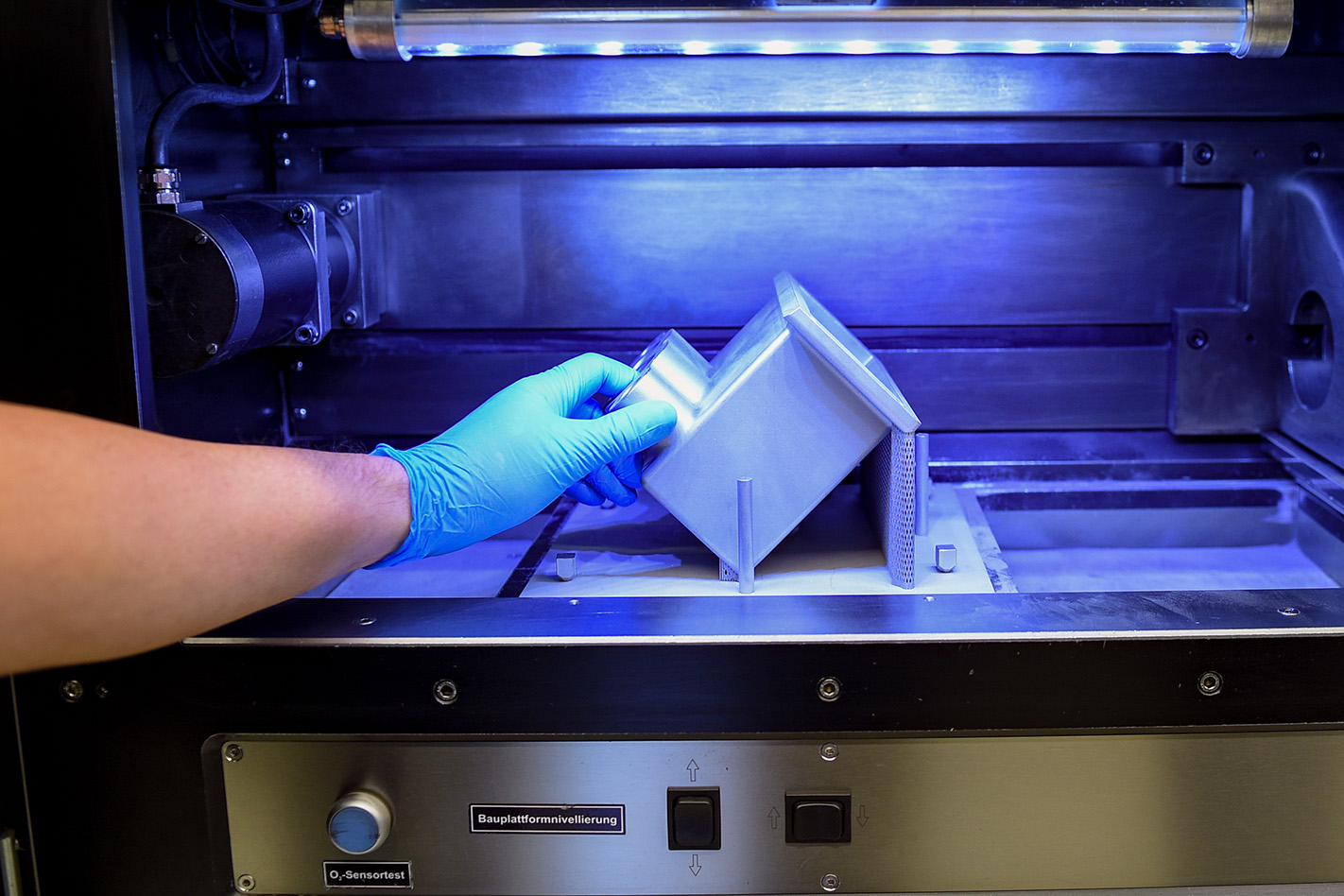

One solution is to replace vast parts warehouses with a room full of 3D printers and a database of 3D models of parts. Parts could then be printed on demand and supplied the same day (or next day) rather than having to be shipped from overseas if local stocks are depleted. Rather than holding inventory of individual parts, the automaker would only need to stock the base materials needed to create them.

For the consumer, that potentially means their car spends less time at the dealership when repairs are needed. For the manufacturer, it means massive cost savings in logistics and real estate.

Manufacturers are experimenting with printing smaller, simpler parts such as door handles or mirror casings, but as metal 3D printing becomes more sophisticated and cost-effective, we could one day see replacement mechanical parts be manufactured on-demand too. However, large parts such as bodywork will likely still need to be made by traditional means.

The likes of BMW, Daimler-Benz and Ford – among others – are all trialling 3D printing technology for their spare parts operations.

Customisation

Mini has made no secret of its plans to enable a higher level of vehicle personalisation through technologies like 3D printing, with high-resolution plastic prints featuring the owner’s name or a custom motif replacing trim pieces throughout the interior and exterior.

The aftermarket wheel industry is also looking into new options, with HRE revealing a hugely intricate wheel design that can only be manufactured using laser-sintered titanium 3D prints. The cost would be eye-watering, but the head-turning effect couldn’t be had any other way.

Parts for classic cars

Cars that have stood the test of time long enough to attain classic status have a slightly different spare part problem – there simply aren’t any.

Beyond what little spares may be lurking in the darker corners of parts warehouses around the world, owners of classics and vintage cars either have to remanufacture or repair their existing parts, or scavenge from other surviving examples. Until now.

3D printing means parts can be scanned, digitised and then replicated in a variety of materials, and given the tiny demand for these parts it’s often more cost effective than commissioning a supplier to do a low-volume run of replica parts.

Porsche Classic recently adopted that method to print nine different parts from a variety of materials, with 20 more parts being evaluated for its on-demand production system. If you’re chasing a brand new clutch release lever for a Porsche 959, you may wind up with a 3D printed item.

Bugatti titanium caliper

Given the high cost of 3D printing compared to traditional methods of mass production, the technology in its present state makes the most sense for cars that are built in low volumes, sell for significant sums and have unique requirements.

And they don’t get much more expensive, complex and unique than a Bugatti.

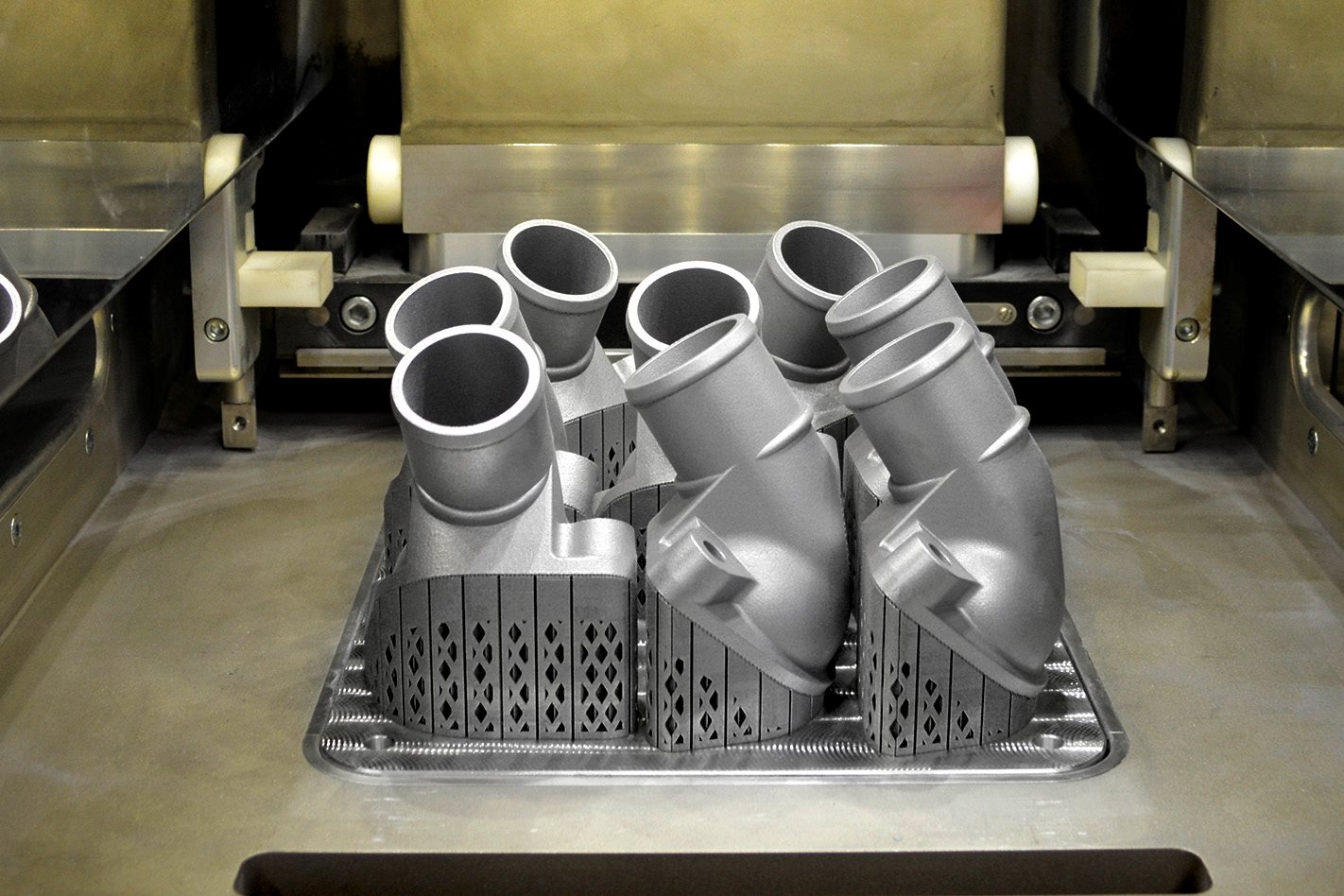

Bugatti, makers of the mind-bendingly rapid Chiron hypercar, designed a brake caliper so intricate and lightweight that it could only be manufactured by 3D printing. Its shape, with many small voids, passages and pockets that would be difficult to machine out of solid metal or cast from molten metal, was instead constructed out of sintered titanium powder by a 3D printer. The result is a monstrous brake caliper that measures 41cm long, 21cm wide and 13.6cm high, yet only weighs 2.9kg.

Each caliper takes 45 hours to print and then requires 11 hours of additional machining to make it a functional part, but the revolutionary aspect of Bugatti’s high-tech brakes is that it’s a part that’s very central to a car’s performance and safety – rather than just a plastic housing for a door mirror.

Koenigsegg One:1 3D-printed turbocharger housing

Bugatti’s 3D-printed brake caliper is almost a work of art, but it’s far from being the first road-going application of a mechanical 3D print. Swedish supercar specialist Koenigsegg employed a printed turbocharger turbine housing in its ballistic One:1 hypercar, exploiting the technology’s ability to create shapes that would be otherwise difficult, impossible, or uneconomical via machining or casting.

Why not just go with an off-the-shelf cast metal item? Because Koenigsegg’s patented variable-geometry turbine required a custom part, but low production volumes meant only 14 housings were required. Just like Bugatti’s brakes, it was the perfect application for metal 3D printing.