Hiroyuki Koba rearranges crockery and cutlery on the crisp white tablecloth of the Madrid restaurant. Having made room for his smartphone, the Toyota chief engineer sets it down between us. A video is already cued and he taps ‘play’.

It’s an over-the-shoulder GoPro view of Koba’s recent last lap at Suzuka, where he races in a series for little tubular-framed open-cockpit sports cars with a mid-mounted Yaris engine. The engineer had started from pole, but as the end of the race draws near he’s in second place. The sound is terrible, like a bug in a bottle, but the vision is excellent. Koba is all over the leader’s tail, but can’t quite engineer a passing move.

It’s on the final corner that he finally overdoes it. The race-leader’s car exits the frame of vision as Koba spins. There’s a glimpse of his own tyre smoke as the car goes round. As it comes to rest, rivals flash past in a colourful, distant blur. This isn’t the sort of thing that normally happens over dinner with Toyota chief engineers, and I speak from long experience.

The new Toyota C-HR, being launched to the world’s media in Spain, is his work. Koba, now 54, has spent the last three decades rising through the ranks at Toyota, working on things like the suspension designs of various generations of Toyota Corolla.

At Toyota, where chief engineers have immense power, Koba wielded it. He won’t tell me exactly how advanced the C-HR program was when he insisted on a switch to TNGA, but it was late enough to delay its launch.

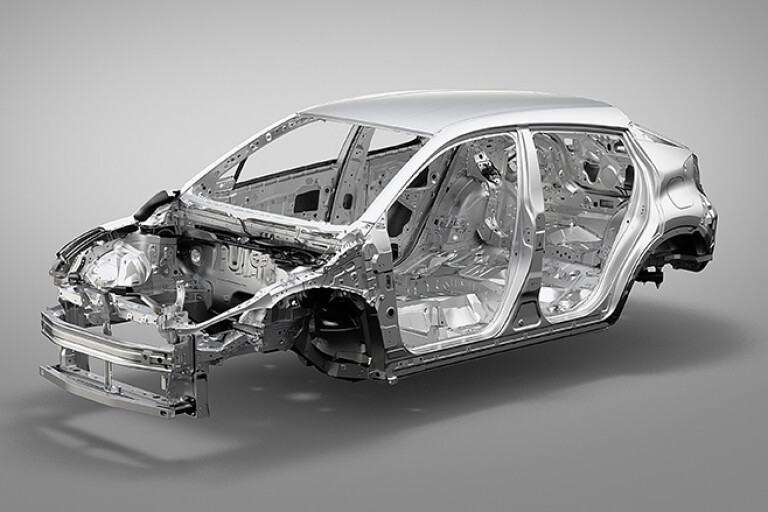

Those letters stand for Toyota New Global Architecture. Think of it as the Japanese giant’s reply to its German opposition. Like the Volkswagen Group’s MQB, TNGA is a flexible component set that incorporates advances in body construction and chassis engineering. The C-HR is only the second Toyota model, after the fourth-generation Prius, built on TNGA.

Specifically, the C-HR uses the GA-C version of TNGA. The coupe-ish crossover has a shorter wheelbase than the Toyota Prius, and a slightly modified version of its multi-link rear suspension. The latter was one of the key reasons why the dynamics-obsessed Koba wanted TNGA so badly. His objective was to create a crossover that handled as well as a good C-segment hatchback. Something like a Golf VII, in other words.

Koba then decided a great way to demonstrate the C-HR’s handling prowess would be to race it. At the Nurburgring. The engineer admits he had an ulterior motive here. “Honestly speaking, I wanted to drive the Nurburgring,” he says.

So Koba made himself a member of the four-driver team for the shorter qualifying race for the mid-year Nurburgring 24 Hour. The C-HR Racing he drove featured lowered suspension, a massive rear wing and a slightly larger version of the production car’s 1.2-litre turbo four, producing around 120kW.

The roadgoing C-HR obviously doesn’t drive exactly like the Ring racer, but it does have excellent dynamics. It has a level of handling poise and precision that’s unexpected in something wearing a Toyota badge. Rides very well, too.

If Toyota keeps promoting talent like Koba, there’s a chance the brand might eventually earn a reputation for delivering driving pleasure to go with its hard-won quality image. And that would be a combination with unbeatable appeal…

Supraman

Hiroyuki Koba really is our kind of chief engineer. As if the racing wasn’t enough, his personal car is a silver fourth-generation Toyota Supra – the final facelifted version from the mid-1990s. Koba uses it regularly. In fact, it’s the car waiting for him at the airport when he returns to Japan.

This article first appeared in Wheels magazine January 2017.

COMMENTS