"Stay in your tent … the lion will visit tonight…”

This feature was originally published in 4x4 Australia’s November 2011 issue

His ivory-white eyes appeared like two searchlights on a stormy South Atlantic coast, and his skin, dark as obsidian, was absorbed by the moonless Kalahari night like the featureless miles of bush surrounding our camp. Climbing into an old LandCruiser trayback, he disappeared into the night.

As the taillights vanished, his last words of advice, “Stay in your tent…” trampled through my subconscious like a stampede of elephants, awakening every childhood nightmare of the boogieman in my closet. I’d spent weeks camping in the wilds of Namibia, South Africa, Lesotho and Zimbabwe.

As the taillights vanished, his last words of advice, “Stay in your tent…” trampled through my subconscious like a stampede of elephants, awakening every childhood nightmare of the boogieman in my closet. I’d spent weeks camping in the wilds of Namibia, South Africa, Lesotho and Zimbabwe.

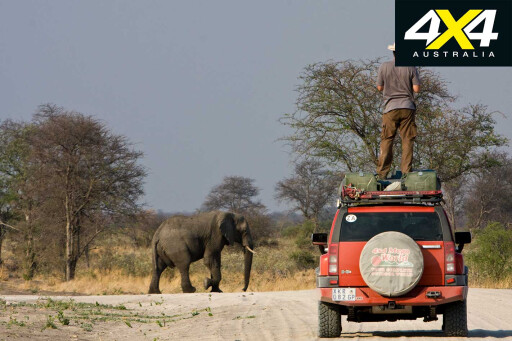

I’d had elephants walk through my camp, baboons steal my food, and caught hyenas patrolling the perimeter of my fire light. But with the park ranger’s final nine words, things instantly changed. What we’d thought would be another tranquil night in the depths of Kalahari, suddenly became one of internal mind games, strange and foreboding noises, and fear.

Four days earlier, we’d crossed into Botswana from South Africa. The other half of ‘we’ was old college buddy, Allen Andrews. We were a week into the adventure of a lifetime. General Motors had offered me a deal I couldn’t pass up – an H3 Hummer … and no time limit.

As a kid, only a few could draw my attention from my dirtbike and endless tracks of the California desert. The first was 4X4 trucks, and the second, oddly enough, was a TV show.

As a kid, only a few could draw my attention from my dirtbike and endless tracks of the California desert. The first was 4X4 trucks, and the second, oddly enough, was a TV show.

Each Sunday my dad would turn on Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom. Sporting safari garb and trekking through a distant land called Africa, Marlin Perkins, would authoritatively describe the deadly prowess of a python or lion, as his sidekick, Jim Fowler, wrestled it into submission. I dreamed of one day pitching my tent on the African savanna and falling asleep to the sound of elephants trumpeting in the bush, lions making a kill and hyenas scavenging for carrion.

As an adult, I never let go of those childhood ambitions. This was my chance to follow in Marlin’s footsteps, to live the dream.

As an adult, I never let go of those childhood ambitions. This was my chance to follow in Marlin’s footsteps, to live the dream.

DARWINISM AND THE FOOD CHAIN

I’d chiselled two months out of my schedule and planned to cross eight countries and cover approximately 10,000 kilometres. Allen would join me for three weeks. After that, I’d be on my own.

Kalahari, which means ‘waterless place’ in the Setswana language, may be one of the most diverse semi-deserts on the planet. And while services are more frequent to the north, the southern Kalahari, from Letlhakeng to Rakops – about 750km of deep Kalahari sand tracks – you are on your own.

Kalahari, which means ‘waterless place’ in the Setswana language, may be one of the most diverse semi-deserts on the planet. And while services are more frequent to the north, the southern Kalahari, from Letlhakeng to Rakops – about 750km of deep Kalahari sand tracks – you are on your own.

A trek through the Kalahari is like stepping into another dimension. One of centuries past, where common sense and preparedness are prerequisites, and Darwin’s theory of evolution rules the bush. It is the realm of the Big Five (lion, leopard, rhino, elephant and cape buffalo), survival of the fittest, and a place where, if you put yourself in the wrong situation, you may become part of the food chain.

I’d hooked up with the guys at 4x4 Megaworld, southern Africa’s largest suppliers of off-road gear, to help with kitting the vehicle. Waiting for us were a Warn 9.5ti winch, high-lift jack, two Optima batteries, IPF lights and a slew of gear from ARB (bullbars, roof rack and tent, compressor, etc.)

The Megaworld crew fitted the gear and even gave me an open-ended shopping spree through their racks of camping gear: chairs, stove, etc. – everything I needed for two months in the bush.

BORDER CROSSING, LAST GAS AND GIRAFFES

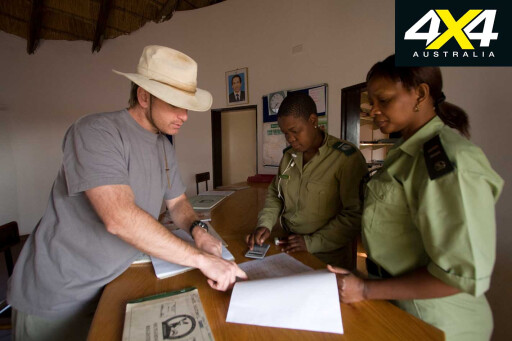

The sun burned a searing orange hole in the morning sky as we passed through the border post at Ramatlabama, Botswana.

Unlike many African border crossings, this one was seamless. Insurance, registration, passports and carnet were in order, the guard issued our visas, stamped everything in duplicate, lifted the gate and we motored through.

Unlike many African border crossings, this one was seamless. Insurance, registration, passports and carnet were in order, the guard issued our visas, stamped everything in duplicate, lifted the gate and we motored through.

Barring any major issues, we’d cover approximately 2500km before reaching the Kazengula ferry to Zambia. The last fuel before entering the Central Kalahari Game Reserves was in Letlhakeng. Ahead lay 750km of soft sandy two-tracks. Topping-up the H3’s 87-litre tank and four jerry cans, about 167 litres in total, we’d need to conserve fuel and avoid costly detours. Running low on fuel would mean a 200km detour to Namibia.

The Khutse Game Reserve, at 2600km2, is but a speck on the map compared with the Central Kalahari (52,000km2). But within its boundaries, the arid landscape stretches into oblivion and feels as though you are entering the burning gates of hell.

The Khutse Game Reserve, at 2600km2, is but a speck on the map compared with the Central Kalahari (52,000km2). But within its boundaries, the arid landscape stretches into oblivion and feels as though you are entering the burning gates of hell.

The sun was setting and we’d knocked off 150 kilometres by the time we pulled into the Molose Camp waterhole. Our first night in the Kalahari, we sat and watched in awe as the fiery orb settled into a distant acacia forest. A giraffe stepped into scene along with a few jackals and a variety of birds.

We stoked up a good fire, listened to the sounds of Africa, and witnessed the passing of a billion stars across the austral sky.

We stoked up a good fire, listened to the sounds of Africa, and witnessed the passing of a billion stars across the austral sky.

THE ROAD FROM HELL AND T’D OFF RANGERS

The thin red line on the map didn’t seem so long, but the trek from Molose to Xade Camp, at 266km, would be a brutal day. The sand of the Kalahari, which is exceptionally dry and fine-grained, made for a gruelling pace.

Fire had swept through the area a few days earlier, and smoke and the smell of charred wood hung heavy in the air. A pair of headlights poking through the haze at dusk, the first traffic of the day. Two couples in hired Toyotas who had spent the day digging out of the sand. They said there was a big military camp ahead set up to fight the fire. With 90km to go, we flipped on the headlights as darkness fell. Suddenly, the guidebook’s suggestion, “don’t travel alone” was gaining credence.

Fire had swept through the area a few days earlier, and smoke and the smell of charred wood hung heavy in the air. A pair of headlights poking through the haze at dusk, the first traffic of the day. Two couples in hired Toyotas who had spent the day digging out of the sand. They said there was a big military camp ahead set up to fight the fire. With 90km to go, we flipped on the headlights as darkness fell. Suddenly, the guidebook’s suggestion, “don’t travel alone” was gaining credence.

Park rules prohibit driving at night, but also bush camping. At the military camp, the soldiers rerouted us to the XaXa camp just a few minutes away. A few minutes turned into 25km and precious litres of fuel, something we could not afford.

It was quite late when we found the waterhole, but there were no signs for the camp and it is illegal to camp close to a water source. We were dog-beat tired and said the hell with it – camp here. About this time another ranger appeared, and an angry one at that. We got our arses royally chewed for not using the official camp.

“It is illegal to camp here, you could be arrested,” he proclaimed, and “I’ll take you there if you can not find it – it is well marked.”

“It is illegal to camp here, you could be arrested,” he proclaimed, and “I’ll take you there if you can not find it – it is well marked.”

There was the sign, and in perfect English, but it was lying on the ground to the side of the track and in the bushes. TIA (This Is Africa).

LIONS, JACKALS AND SCARES… OH MY!

As the sound of the ranger’s LandCruiser faded into the darkness, our first thoughts were, ‘we need to get a fire started.’ Allen volunteered to manage spotlight duties, while I scrounged the edge of the bush for dry grass.

My heart raced, eyes trained intensely into the darkness, the words “stay in your tent” swept through my mind. Allen panned the brush with the torch and shadows seemed to grow, dart to one side, and disappear with each pass…it was the boogieman, I knew it! And as tough as you think you might be, when you are tossed into the food chain, and you’re no longer at the top, you become a lily-livered weak-kneed chicken.

My heart raced, eyes trained intensely into the darkness, the words “stay in your tent” swept through my mind. Allen panned the brush with the torch and shadows seemed to grow, dart to one side, and disappear with each pass…it was the boogieman, I knew it! And as tough as you think you might be, when you are tossed into the food chain, and you’re no longer at the top, you become a lily-livered weak-kneed chicken.

I collected a few handfuls of grass and quickly scrambled back to the safety of the camp. Lions have a distinct roar, and they did come to visit. Through the camel thorn acacia and scrub brush, we could hear the unmistakable call of a pride of lion on their nightly hunt. Even with a campfire blazing, the ARB camp light on and strobe in hand, we didn’t stray far.

The fuel light came on as we reached Xade military Camp. The fire had grown to 20,000km2 and was moving fast across the Kalahari. “It could be dangerous, be very careful,” we were told.

Though we had 80 litres of fuel on our ARB roof rack, the extra 50km to Xaxa Camp had pushed our previous range estimates over the limit. The decision was made to head to Ghanzi for fuel (250km return). Two nights later we’d set foot on the edge of Deception Pan.

Though we had 80 litres of fuel on our ARB roof rack, the extra 50km to Xaxa Camp had pushed our previous range estimates over the limit. The decision was made to head to Ghanzi for fuel (250km return). Two nights later we’d set foot on the edge of Deception Pan.

DECEPTION PAN, WILDFIRES AND T4A

Deception Pan was launched into the global limelight in the ’80s by a pair of young zoologists, Mark and Delia Owens. Living in tents on the edge of the pan for seven years, they studied the wild dog, hyena and lion, and published a book, Cry of the Kalahari. Allen had a copy of the book and had been reading me excerpts.

Driving around the pan, we identified the Tree Island on which they lived and envisioned life in this truly remote and wild place. Smoke rolled in like a fog bank as we headed back to camp – by dusk we could see the faint orange glow to the southeast. Fire! Strong hot winds blew from the south and the faint glow was growing and moving.

By 2300hrs, we were getting concerned. We packed everything for a possible quick departure and set our alarm for three hours. We were awakened by the smell of smoke. Peering out window of our ARB tent, the entire horizon was fiery red, flames whipping into the air like a crimson geyser. “We need to get the hell out of here.”

By 2300hrs, we were getting concerned. We packed everything for a possible quick departure and set our alarm for three hours. We were awakened by the smell of smoke. Peering out window of our ARB tent, the entire horizon was fiery red, flames whipping into the air like a crimson geyser. “We need to get the hell out of here.”

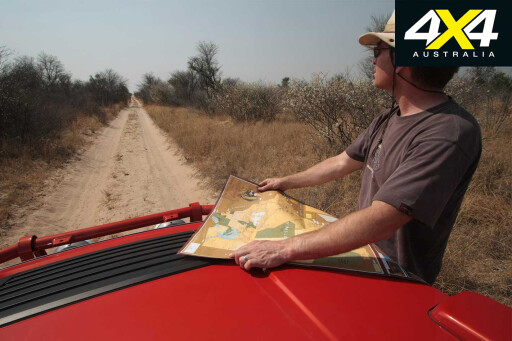

On my first trip to Africa, my only navigation aids were a set of maps and compass. But, with today’s technology and software, I had sourced a Garmin GPS and Tracks-4-Africa (T4A) software. T4A is by far the coolest thing since the invention of four-wheel drive. It details almost every highway, dirt road and two-track on the African continent, and was literally a lifesaver at this point.

Our planned escape route was north, around Deception and to the Mangana park gate, and that put us on a collision course with the rapidly moving fire. If we couldn’t get in front of it, we’d have to retreat to the west.

By the time we reached Deception Pan, the fire had encircled its southern end and was running north up both sides. Smoke and ash swirled through the cab and across our headlights as the road zigzagged east towards the fire, then north, then east again. We were certain that the fire had already crossed the road behind us, so turning back was not an option.

By the time we reached Deception Pan, the fire had encircled its southern end and was running north up both sides. Smoke and ash swirled through the cab and across our headlights as the road zigzagged east towards the fire, then north, then east again. We were certain that the fire had already crossed the road behind us, so turning back was not an option.

Option two was to park in the middle of the pan, let the fire burn around us, and wait it out. We didn’t like that one either.

With maps and a compass we would have been toast… Well, maybe barbecued. But the T4A map detailed the track precisely, and the decision was, “Drive … fast!” The flames ran like the wind and were within a few hundred metres of us by the time we got in front of them.

When we reached the park gate at 0400, a ranger and a few Brits greeted us and said, “We didn’t know if you mates were going to make it. All we could see were the flames, and two headlights coming out of the red fire.”

When we reached the park gate at 0400, a ranger and a few Brits greeted us and said, “We didn’t know if you mates were going to make it. All we could see were the flames, and two headlights coming out of the red fire.”

The trip meter clicked 3339km as we rolled through the Mangana gate and headed for Rakops for fuel. We’d covered 1097km through the Kalahari’s deepest sand tracks, been visited by lions and hyenas, walked in the footsteps of a childhood hero, and survived the biggest fire in recent history. By 0600 the winds had shifted and all seemed calm.

As the sun prepared for the daily arrival, it cast a golden pallet of orange, crimson and ginger over the scorched landscape.

MAKGADIKGADI, BAOBABS AND THE OKAVANGO

The searing austral winter heat was pressing against the windshield, whipping through my open window like a glassblower’s furnace. My legs, now a crimson tone, are reeling from the previous seven days of exposure to the intense sun and forty-plus-degree temperatures.

I could have reached down, hit the aircon and slid the power windows to the up position. But no, I was following the tracks of one of my childhood heroes and the explorers of centuries past, Marlin Perkins, Henry Stanley and Dr Livingstone, and had vowed not to cave in to modern conveniences; save the Hummer H3.

I could have reached down, hit the aircon and slid the power windows to the up position. But no, I was following the tracks of one of my childhood heroes and the explorers of centuries past, Marlin Perkins, Henry Stanley and Dr Livingstone, and had vowed not to cave in to modern conveniences; save the Hummer H3.

We’re heading towards the Boteti River, the Makgadikgadi and Nxai Pans, and the aqueous reaches of the Okavango Delta. Rakops is no more than a few dozen rondavels and a dirt main street. But it possesses all the necessities for an African road trip – two garage-sized markets and a fuel pump. With full tanks and a few sundries into our fridge, we went in search of the decade-dry Boteti River.

Rumours were drifting through the bush that floodwaters from the Angolan highlands were pushing south, and that the historically dry web of channels, including the Boteti, may have water.

Locating a faint track from the tar road, we headed east to its terminus at an abandoned camp. A game trail led us a few hundred metres through thick bush to the steep banks of the Boteti. Void of water, we shoehorned the H3 down through a maze of acacia, and were greeted by a very surprised herdsman and a few dozen cattle. It appeared that he’d been living with his cattle for months, maybe years, pumping (and drinking) water from a hand-dug well and sleeping under a tree.

The language barrier was broken with a smile, a bottle of clean water and a small piece of quickly melting chocolate. Bewildered, he attempted to put it in his pocket for later. We assured him he should eat the chocolate immediately.

The language barrier was broken with a smile, a bottle of clean water and a small piece of quickly melting chocolate. Bewildered, he attempted to put it in his pocket for later. We assured him he should eat the chocolate immediately.

From treetop perches, black-breasted snake eagles kept a curious eye on us as we followed the riverbed upstream in search of the oncoming flow. Reaching the boundary of the Makgadikgadi Game Reserve, and unsuccessful in our quest in the Boteti, we climbed the east embankment into Makgadikgadi and would continue our search in a few days.

Herds of zebra and wildebeest greeted us within 200 metres of the park gate. We’d transitioned from agricultural Botswana to the realm of the wild. Outside the gate, people hunt for subsistence and commerce, and the remaining wildlife competes with cattle for limited resources. But within the reserve’s four-metre-high game fence, the bush appears in a constant state of motion.

Springbok and gemsbok peer from camouflaged veils of mopani, and vervet monkeys play their mischief while keeping a vigilant eye out for predators. The Makgadikgadi lies on the footprint of ancient Lake Ngami.

Most of our maps showed the region as a large blue form and, based on its endorheic disposition, this most assuredly meant a lake surrounded by savanna. Wrong! The blue only indicated where a lake would be if Noah were preparing his ark for departure. And rather than one massive dry lakebed, or pan, Makgadikgadi is a compilation of dozens of small pans, broken by islands of yellow prickly salt grass, acacia and scrub.

Most of our maps showed the region as a large blue form and, based on its endorheic disposition, this most assuredly meant a lake surrounded by savanna. Wrong! The blue only indicated where a lake would be if Noah were preparing his ark for departure. And rather than one massive dry lakebed, or pan, Makgadikgadi is a compilation of dozens of small pans, broken by islands of yellow prickly salt grass, acacia and scrub.

It was just before sunset when we arrived at Nxai Pan. Matusi, a young park ranger, pointed us to our camp on the map, laid down the park rules, and urged us to get out to the South Waterhole to view the wildlife.

As the sun dissolved into a fiery orb in the western sky, we blasted across the ancient lake bottom towards the Baines baobabs. Perched on an island, this mini forest of baobabs gained notoriety via the late 18th-century painter Thomas Baines, who set their macabre forms to canvas.

Pulling the H3 to the edge of the saltpan, we deployed the ARB tent, quickly scrounged some grass to start our nightly fire and, after picking out the bones, dined on gourmet cuisine of canned chicken curry. A cool breeze softened the relentless heat of the day, and we’d share camp this night with a few black-backed jackals beneath the ghostly moon shadow of these prehistoric giants.

Pulling the H3 to the edge of the saltpan, we deployed the ARB tent, quickly scrounged some grass to start our nightly fire and, after picking out the bones, dined on gourmet cuisine of canned chicken curry. A cool breeze softened the relentless heat of the day, and we’d share camp this night with a few black-backed jackals beneath the ghostly moon shadow of these prehistoric giants.

Unlike me, Allen is not the kind of guy who can wear the same pair of underwear for a week (the trick is to go commando, or turn them inside-out on day four, then wash or burn them on day seven).

It was time for another shower, and rather than surrendering to the tar road to Planet Baobab – a funky retreat to the east – we attempted to locate a thin dotted line on our map, the traditional Maun-to-Gweta route.

Although we eventually found the long-abandoned track, it had been closed by the government and the better part of the day was lost in the effort. But cold beers, a hot meal of game stew and a double bunk rondavels awaited. So we swallowed our pride, endured a few dozen kilometres of pavement, and an hour later were tossing back coldies.

MOREMI, CHOBE AND THE JEWEL OF AFRICA

We’d been in-country for thirteen days, set up our transient camp each night, and spun almost two thousand kilometres on the odometer.

The following morning would find us in Maun (Ma-oon), gateway to the Okavango Delta—The Jewel of Africa. One of the world’s largest inland water systems, the Okavango receives an annual 18 billion cubic metres of floodwater from the Angola Highlands. It is a world of rivulets, palm-lined channels and forested islands, and home to thousands of species of African flora and fauna.

The following morning would find us in Maun (Ma-oon), gateway to the Okavango Delta—The Jewel of Africa. One of the world’s largest inland water systems, the Okavango receives an annual 18 billion cubic metres of floodwater from the Angola Highlands. It is a world of rivulets, palm-lined channels and forested islands, and home to thousands of species of African flora and fauna.

Due to perennial flooding in much of the delta, there isn’t a direct route from Maun to Chobe and Moremi, and the tar road is a 280km detour.

There are two Botswanas – that which lies outside the game fence, and that which is inside. The outside is void of indigenous species, and all you see are cattle and agriculture.

Inside, however, elephants and giraffe walk across your path, leopards nap lazily from limbs of sausage trees waiting for an unsuspecting baboon, and if you stray to into the bush on foot, you might find your place somewhere in the food chain.

The next four days in Moremi and Chobe Game Reserves would be just that: Elephants, giraffe, kudu, eland, vervet monkeys and baboons. It was like driving through Wild Country Safari, but with no fences, caution signs or traffic.

The next four days in Moremi and Chobe Game Reserves would be just that: Elephants, giraffe, kudu, eland, vervet monkeys and baboons. It was like driving through Wild Country Safari, but with no fences, caution signs or traffic.

North of Maun, the track came to an abrupt end at the edge of the Khwai River. It continued on the other side, and the local villagers said the government was working on a bridge, but hadn’t done anything in several years.

New plan: head up-river to a spot shallow enough to cross (and not congested with elephants, hippos or crocs), and enter the Moremi at the north gate. After navigating a web of tracks we found a crossing, located a suitable winch anchor in case we got stuck, scanned the banks for crocs, and forged across.

Camps in Moremi are named after the log bridges they are near, and our destination was Third Bridge Camp on the remote finger of the delta. The area is a massive floodplain, and in the dry, water is usually low enough to pass safely. Ninety kilometres and a dozen water crossings later, we wandered into camp at dusk.

Camps in Moremi are named after the log bridges they are near, and our destination was Third Bridge Camp on the remote finger of the delta. The area is a massive floodplain, and in the dry, water is usually low enough to pass safely. Ninety kilometres and a dozen water crossings later, we wandered into camp at dusk.

We made a quick bush-forage for firewood. And, upon returning, the ranger informed us “A leopard made a kill where you just were last night; stay near camp.” Knowing that Zambian fuel was three-fold the cost in Botswana (US$12 vs US$4), we topped the tank and jerry cans and headed for the Kazengula Ferry.

It had been 18 days since we entered the Kalahari. I’d be dropping Allen at the airport the next day, and be on my own for the next month. I slipped a well-worn Botswana map in the glove box, pulled out Zambia, and unfolded the next chapter of my childhood dreams of following the footsteps of Marlin Perkins and exploring the Dark Continent.

COMMENTS