How hard could it be to use only the dirt between the borders of Mexico and Canada? That dirt being the USA!

A light haze is drifting like a translucent blanket above the western horizon. The afternoon sun, like a retina-burning laser, sears a hole though the fiery orange soup.

Adjusting my visor to the down position, the rays underscore my blind. Squinting, I sit up straight to ease my eyes. The mid-June air is warm, but not unseasonable. After all, we’re crossing a fissured and desiccated dry lake in the middle of the southern California desert. I make out a shape in the distance that begins to take form as we approach.

I lean over to my driving buddy, Del Albright, and say, “Does that look like two guys sitting under a tarp?” Del laughs, smiles and looks on. We’ve hardly seen anyone for days, since we left the Mexican border; Del probably thinks I’m seeing a mirage, or suffering from heatstroke. With a second glance, his expression turns serious; he flicks off the radio and is all business. “Soldiers.”

Startled by our stealth approach, one of them appears to reach for an M16 as he leaps from his chair. We slow down as he approaches Del’s open window. About nineteen years of age, he is wiry, fit, and energetic. Del’s smile returns. “Where did you guys come from?” PFC Zach declares in a Texas drawl, “They got live bombing exercises going on, we’re supposed to be keeping people outta there.”

FIVE DAYS FLASHBACK

I’d been day-dreaming of doing a major overland trip for some time. And, unlike past adventures like crossing the Kalahari or trekking through Morocco, this needed to be an adventure that anyone could do. The other criteria was that it needed to be in a region where AK-47s are not standard issue for teenagers, and inoculations not required.

I’d received an assignment in British Columbia, Canada, which sparked the idea. But where to start and what would make this an epic adventure? Logic determined that I should start at the beginning, or, in this case, the bottom. Mexico! The next obstacle was to carve twenty-plus days out of my schedule.

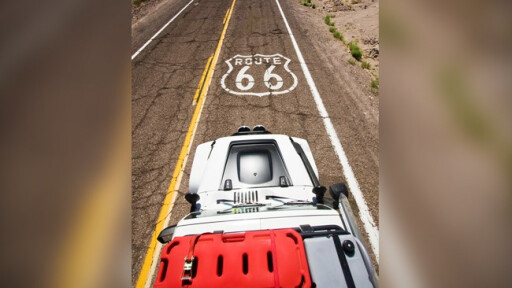

My flight home from BC hit the tarmac at 0030. I slept for four hours, Del arrived at 0600, and we headed for Los Angeles. I’d talked Jeep’s brand manager, Scott Brown, into loaning me a four-door JK for three weeks. It wasn’t your average JK; it was the Overland, one of Mopar’s Underground Engineering concept vehicles – a real head turner.

I was introduced to the Overland while shooting Mopar’s Trail Calendar in Moab, Utah. Sporting an ARB roof rack and Series III tent, AEV bumpers, a Warn winch with Viking winch rope, it oozed adventure from every angle. The 35-inch BFG KM2s didn’t hurt the ‘we’re cool’ profile either. At 1500 hours, and 700km later, Scott handed us the keys and we headed for the Mexican border.

As the crow flies, Google Earth pegged my route to be 1816km. Yahoo Maps came up with 2448km (about 27 hours if you don’t stop for fuel, food or potty breaks). Well, we’re not birds and Yahoo gives the direct route – on tar roads, which is boring. So, how far would it be on the road less travelled – the dirt track – and how long would it take?

NEW MATES AND FIGHTER JETS

The Mexican border cuts across the Algodones Sand Dunes, stretching east for 3000km to the Gulf of Mexico. In places, this high-security demarcation is no more than a bold red line on a government map. In California, though, zona de internacional is a three-metre barrier resembling thousands of cattle grids standing on end. It also sports a 30-metre restricted area on the US side.

How do we know this? We parked ten feet from the ferrous fiend and within five minutes a half-dozen US border agents converged on us like Radar (my dog) on an unguarded bag of beef jerky. As we parted, I mentally queried what I would encounter when I nosed the JK’s bumper against the 49th parallel (Canada).

My research revealed that there would be too much snow in Montana and Idaho, so we’d stick to the Wild West: California, Nevada, Oregon and Washington. I slipped in a Jimmy Buffet CD, reset the trip meter, switched on Spot (our satellite transponder) and turned the wheels north.

251km: Slab City is one the most God-fearing and bizarre enclaves one will behold. Passing through was like a 20-minute acid trip through a sectarian Tom Petty video. We parked at the base of God Mountain; a fifty-foot man-made precipice rising from the desert floor, and poked around the various forms of Godly art. The population is only a few hundred and we didn’t see a soul, but we sensed we were not alone.

With all forms of modern navigation technology at hand, one would think we’d know where we were going. Not so! A few hours later we were being escorted out of a bombing range by a civilian-looking guy in a hired cargo truck. We didn’t believe him until a couple of jets did a low pass on our position and disappeared over the next range. Plan B: We diverted to the Bradshaw Trail through the Orocopia Mountains, cut north and headed for Joshua Tree National Park.

My Jeeping mate, Del, is a perpetual joker. He’d also done several tours in the military and knows how to roll with the punches; a good guy to travel with. He’d ride with me for ten days, to Reno, Nevada, where I’d kick him to the curb in lieu of my lovely (and much better looking) wife.

KILLER BEES, MARINES AND M16S

Our intended route into the park had a gate across it, and a road closed sign. It was clear at this point that the all-dirt aspect of our trek to Canada would need to be modified slightly to find fuel, access the national parks and skirt around numerous military bases.

In the north-east corner of Joshua Tree NP is the Old Dale Mining District, which had its heyday in the 1880s. After a close encounter with a rattlesnake, we hunkered down for the night near a decaying ore rig. As our fire illuminated the canyon walls, we cracked open a few coldies, gazed at the drifting constellations and surveyed our maps.

336km: Skirting the Twenty-nine Palms Marine Base (more bitumen) put us on the east side of Johnson Valley, home of the King of the Hammers. It was late afternoon when we met our new Marine buddies, Zach and Nick and their M16s. The soldiers had been dropped off with a case of MREs (meals ready to eat), radios and a few jugs of water. And the M16s? Only our vivid imaginations. However, with heightened US military activity, we’d need to keep a closer eye on our maps.

520km: The 1800s US policy of Manifest Destiny was the impetus for the expansion of the iron horse across the west. And in the days before the automobile, railroads became an expedient lifeline to the east. The map indicated our track continued past the Topeka-Santa Fe railroad – and it did, but there was no crossing. Del raised an eyebrow, laughed and turned up the radio. I slipped the JK into low-range, jumped the tracks and headed towards the Mojave Desert.

Encompassing much of Old Mexico (Southern California, Nevada and Arizona), the Mojave ranges from barren salt flats to palm-lined oasis – a must-do.

Death Valley summers can chase the mercury well past the 45 degree C mark, and it was 27 degrees C when we awoke in our camp near Warm Springs. Del already had the coffee hot, and the harmony of Jimmy Buffet’s Four Lonely Days drifted through camp. It became a mascot song of sorts, and numerous karaoke auditions would occupy the cab in upcoming days on the road.

The route of our previous day, Henry Wade Road, holds a secure footing in the region’s annals. Though written accounts vary as to the number of desiccated souls left behind by the first wagon train to stray into Death Valley, no one disputes how the area received its moniker. A survivor of the ill-fated 1849 expedition, Henry Wade returned the following year en route to California with his family.

Again faced with dwindling supplies, Wade acted on a hunch that an old Indian trail would lead his group from this hellish wasteland. Decades later, in the 1880s, 20-mule teams of the Harmony Borax mines used this route to haul ore to the new Mojave Rail Station.

The route from Warm Springs to Goler Wash is not to be missed. Striated canyon walls stretch high from the valley floor, peppered with decaying mines and cabins. Goler Wash is a narrow and hidden cleft in the western slope of the Panamint Range. Though commonly known for its access to Barker Ranch, the 1969 hideaway of Charles Manson, the canyon was actually named after John Goler, a member of that first wagon train in 1849. We kicked around the charred remains of the ranch before heading to the ghost town of Ballarat (population: three) to visit George ‘Big Hands’ Novak.

Settled into an old blue office chair like a comfortable cat, George, now in his late 80s, is no stranger to the desert. Arriving in 1947 to do some prospecting, he took a liking to solitary desert life. Six decades later, his mining days are of a bygone era. His new gig is managing the Ballarat store, museum and post office with his son Rocky. We shared cold Cokes, while George spun yarns of desert days past, and Del banged out a few tunes on the piano.

800km: Saline Valley spreads out from the base of Grapevine Canyon. Beyond are the Saline Valley Hot Springs. Once a refuge for hippy fallouts from the 1960s, the palm-lined paradise is surrounded by desert. As we set up camp, afternoon shadows stretched across the valley while two stray coyotes eyed us from a distance. Long overdue for a bath, we grabbed our towels, a bottle of Patron Tequila (tequila: it’s a Yankee thing), and slipped into the hot springs for a fiesta under the stars.

1230km: Bodie, CA, latitude N38 12’ 46”. A chilly wind blew through the paneless wood-framed windows of a 19th century church, kicking up a swirl of dust as it exited a pair of open double doors. Down the street was one of Bodie’s sixty-five saloons: dusty beer pitchers on the bar, pool cues leaning against the wall – yet void of life. It appeared as if the entire town just up and moved one day. This was Bodie.

With a reputation for gunslingers, gamblers and ladies of pleasure, the people of Bodie have never minced words when it comes to hard rock mining, drinking or pay dirt. In its heyday – around 1880 – preachers and ladies of society had moved to Bodie in an attempt to save the township from Satan. They were a hardy lot, and, as winter snows encapsulated the town (which sits at 2530 metres), most folks stayed the course.

The steam engines continued to whistle, town folk shovelled snow tunnels, and proper church services were still held on Sunday. The famous quote, “Goodbye God, I’m going to Bodie,” was penned by a young girl whose family moved to Godforsaken Bodie from the refinement of San Francisco.

TOMBSTONES, BUCKET OF BLOOD SALOON, AND THE BIGGEST LITTLE CITY

We’d crossed into the state of Nevada, the sky was clear and cold, and the compass beckoned north. Antelope darted across the track as we traversed a narrow canyon to Fletcher Junction and the remnants of the Pine Grove mining district.

One of the truly special things about Nevada is that the Wild West and wide-open spaces remain. And you can get just about everywhere on a dirt track, if you choose. We slipped down to Smith Valley for fuel before traversing the lee slope of Mount Como, through the Como Mining District and on to Virginia City. As the days on the road became weeks, the JK cab was taking on the aroma of a dirty sock bag, and we figured a hot shower, some good grub and a few coldies were in order. Just past 10pm, we wandered into the Bucket of Blood saloon. The origins of the name were a mystery to us, but we speculated that somewhere in the mix of drunken miners and handy revolvers, tempers flared and blood was spilled.

1646km: The skyline of the World’s Biggest Little City came to view as we descended Rattlesnake Mountain into Reno, where I’d be joined by my lovely wife Suzanne.

JOHN FREMONT, THE SMOKE CREEK DESERT AND BRUNO’S

Colonel John Fremont, a civil war veteran and explorer, was the first white man to glimpse the deserts of northern Nevada. His charge, from 1841 to 1846, was a government-funded survey of the Oregon Territory and Sierra Nevada Mountains. After meeting Kit Carson on a Missouri riverboat, and working together on several westerly expeditions, the two left St Louis with 55 men for a five-month survey of the west.

On January 5, 1843, ground-fog obscured visibility to 30 metres, many of their livestock and horses had died or been stolen by Indians, and Fremont’s crew needed greener pastures. A scouting trek revealed the waters of Pyramid Lake to the south and the Smoke Creek Desert (named for the rising smoke from Indian campfires through the fog). We speculated that Fremont’s vantage point may have been the peak to our east as we veered north on Winnemucca Ranch Road.

1830km: We lit our campfire in the lee of Eagle Head Peak at around dusk. Looking out over the Smoke Creek Desert, we couldn’t help but envision the heavy fog that Fremont and his men witnessed. Smoke rising from scattered Indian camps was a constant reminder that they were not alone. Unlike Fremont, however, we were only graced with the howl of a lone coyote that night.

In the town of Gerlach, Nevada, there is a sign that reads: ‘Gerlach, where the pavement ends and the West begins’. My departure from the Mexican border seemed like a distant memory. The trip meter clicked 1890km, just a bit more than Google Earth’s estimated as-the-crow-files distance from Mexico to Canada, and we hadn’t even made it to Oregon yet. We still hadn’t unspooled our winch, but the snow and felled trees to the north would undoubtedly change that. Topping up our fuel and water, we nosed the JK onto the Black Rock Playa, a 50km-long alkali flat. Beyond lay the High Rock Canyon, the Trail of Death and Oregon Territory.

COMMENTS