I first met Denis Bartell when I was editing an outdoor magazine and he was about to walk across the Simpson Desert. By then, the mid-1980s, he had already carved a name for himself thanks to some truly incredible exploits in the desert.

Later, when I was first editing this mag, I met him again on a number of occasions while he was walking and canoeing the desert country and its rivers, as well as developing his DB Swag, a precursor to all the modern fully enclosed swags we see today. Just recently we caught up on the phone and talked of those old days.

His first crossing of the Simpson was in July 1977, when he set out from Cape Byron to make a double crossing of the continent. He had planned for the east-west crossing of the Simpson to be entirely cross-country and to pass close to the centre of the desert. We chatted about that and I asked him how he navigated across the dunes before GPS and live mapping.

“Well, I never could use a sextant – too lazy to learn, I guess,” he said, “but I’d take a compass bearing on a tree, a bush or, more rarely, a prominent dune crest, and then for the next 15 minutes or so I’d stay on course by keeping the shadow of the antenna, or whatever, and its position across the bonnet in the same place, and that kept me on course.”

It was a quick and handy way to navigate and Denis was pretty good at it, as on subsequent trips he found many historic points that had eluded sextant-wielding searchers. He also managed to set a record or two.

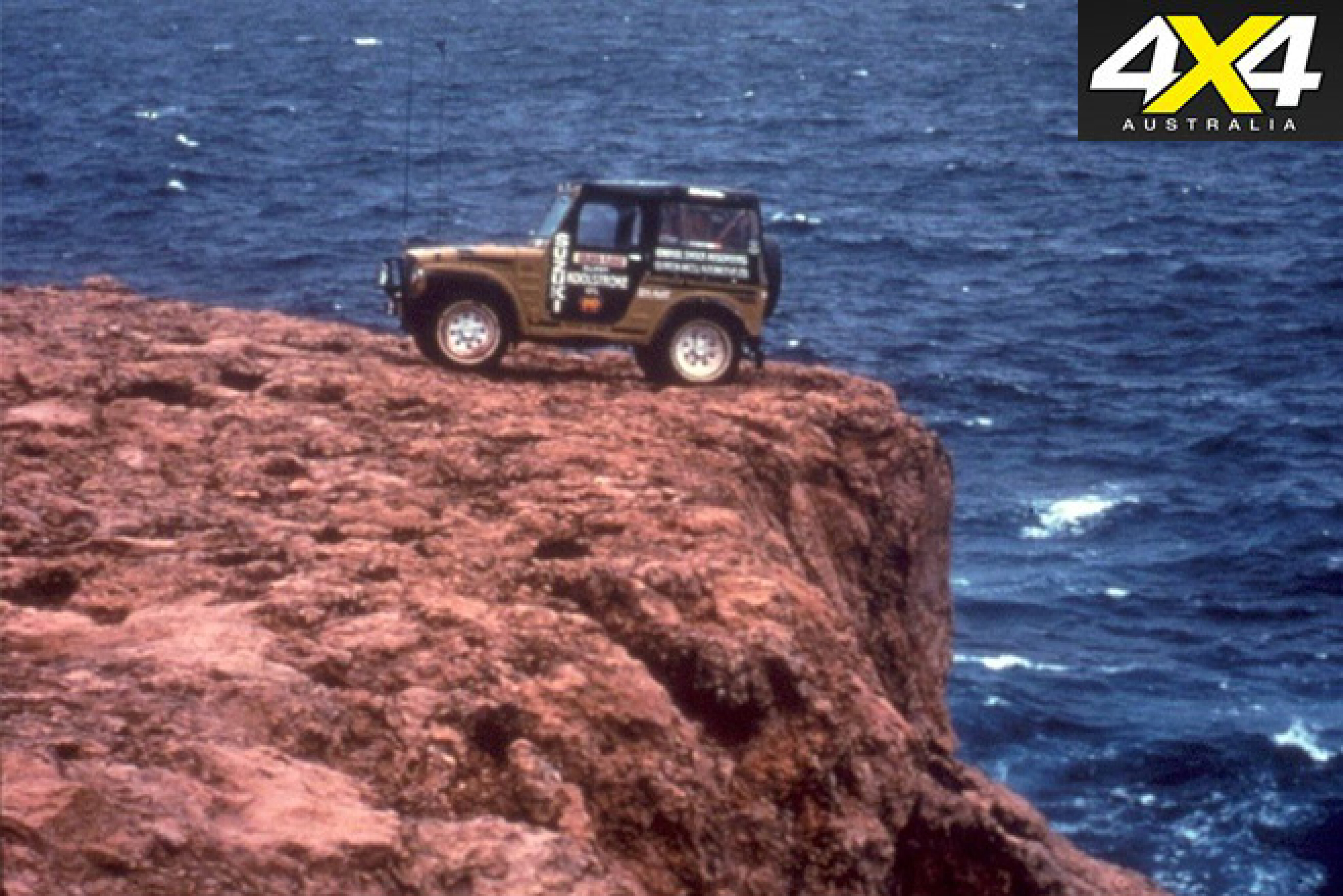

In 1966 the Leyland brothers pioneered a route from Steep Point to Byron Bay, taking more than 110 days. In the 1970s Hans Tholstrup, in a Daihatsu four-wheel drive, completed the first solo one-way crossing of the Australian landmass – in just 13 days. Denis was out to beat Tholstrup’s time, and Suzuki was sponsoring him to do it.

Denis set off in a 25kW three-cylinder, four-stroke, 540cc Suzi and faced numerous challenges: he was hung up on spinifex clumps, he teetered on a roll-over on various occasions, and he only saw a couple of other hardy souls throughout his journey, including Robyn Davidson, whose book Tracks went on to become a bestseller and later made it to film.

Despite all this, Denis successfully crossed the country from east to west. Then, on the return trip (west to east), he beat Tholstrup’s time, cutting the record to nine days, two hours and 20 minutes. Not even a busted front axle could stop him.

The following year he set out again, this time in a more powerful 800cc Suzi, for a record-breaking west-to-east crossing. Plagued by rain and flooded claypans and roads, he set a time of six days, 22 hours and seven minutes. That time still stands as the record for a crossing by a solo driver.

In 1979 he set out on another first – to follow Cecil Thomas Madigan’s 1939 route across the northern Simpson. With him was the then editor of Overlander magazine, Michael Richardson. In a couple of Suzukis – an LJ80 hardtop and an LJ81 trayback – the two men left Molly Clark’s new Andado Homestead and travelled via Old Andado to The Twins and Fletcher Hill, before plunging into the heart of the desert.

A few days later they discovered Madigan’s blazed tree on the Hay River, before pushing onto Kuddaree Waterhole and finally reaching Birdsville. Today, few intrepid desert travellers take on the challenge of this cross-country route, though it’s now made easier by GPS and the known and marked location of all of Madigan’s campsites.

The following year saw Denis back in the desert, this time in a shorty Land Cruiser, achieving what I believe was his greatest feat in a vehicle in the Simpson. With his teenage son, Richard, they headed east from Dalhousie in the footsteps of David Lindsay’s 1886 expedition. Denis went on to cross the southern Simpson, using his tried and proven navigation method to discover six of the eight Aboriginal wells found by Lindsay. He also found two of Lindsay’s blazed trees.

A government-sponsored expedition around the same time failed to find any of these wells and Denis was later asked to find the remaining two wells, which he did in 1983 when he took a group of archaeologist to all eight wells. In 1981 he discovered another well that was mentioned but never visited by Lindsay.

In 1984 he set out on another ground-breaking trip. This time it was on foot but again across his beloved Simpson Desert, from Alka Seltzer Bore to Birdsville. Using the old Aboriginal wells he had rediscovered on earlier forays, his route was not a straight line but a long sweep south, taking in the life-giving waters of the wells. That crossing – the first unaided walking crossing of the desert – took 24 days, and though he survived it, his body was a wreck by the time he finished.

Still he hadn’t had enough of desert travel, and the following year, after recovering from his previous exploit, he set out on his greatest physical challenge yet – a walk from Burketown on the Gulf of Carpentaria to Adelaide on the Gulf of St Vincent, via, of course, the Simpson Desert.

His gulf-to-gulf expedition wasn’t without its dramas or challenges, not the least of which was his pair of old knees that failed him before he entered the northern section of the desert.

While many people would have given up, Denis simply changed from doing an unsupported crossing to having an air drop, which meant he needed to carry less food, and, importantly, water. His 2500km trek across the continent took five months, and after that challenge his knees were operated on.

In late 1985 Denis was again seeking new adventures when he became the first person to drive a solar-powered car from Darwin to Adelaide. The following year, he was back leading an expedition to all the wells he had previously discovered in the Simpson for the South Australian Department of Environment. He then went prospecting for gold across the outback for a few years.

Denis was back in SA when, in mid-1989, the Cooper and its tributaries came down in flood. Here was an unmissable chance for an adventure and, with almost four metres of water running over the causeway at Innamincka, he pushed his canoe into the flow farther upstream at the Nappa Merrie crossing, and set out for Lake Eyre.

With Denis confused by the many channels through the huge lignum swamps, the trip was no walk – or paddle – in the park. Many channels were dead-ends and he spent a number of nights sleeping in his swag on top of all the gear in his canoe.

Still, there were days and nights spent in blissful isolation, with just the birds and wildlife to disturb him; some places were so pleasant he stayed two nights at them. After six weeks and with the flood not big enough to carry him through to the Birdsville Track, he hid his canoe and headed back to civilisation.

After a couple of weeks’ break he returned to his journey to the Track, though the flood had still not reached Lake Eyre. He was elated to have come so far but disappointed that he had not been able to reach the great lake.

In 1990, however, a bigger flood oozed down the rivers towards Lake Eyre. This time Denis could wait for the water to make it all the way before, in early October, he set out from the ferry point across the Cooper and entered Lake Killamperpunna. Three days of hard consistent paddling brought him on to the waters of Lake Eyre. He was then one of the very few people to have paddled the Cooper all the way to the lake.

That year he received an Order of Australia medal for his achievements, followed in 1994 by the Australian Geographic Society’s gold medal, as Adventurer of the Year.

In early 1994 Denis tracked down Ted Colson’s son, Danny, and with the legendary Noel Fullerton lending Denis a string of his favourite camels and giving him some training in their use, Denis and Danny set out from Bloods Creek in early August of that year to follow in Danny’s father’s footsteps. They headed via Mount Dare out along the Finke River flood-out country to the now capped Dakota Bore. They then went south to the well-visited Purni Bore.

From there the route went east towards the Approdinna Attora Knolls, a popular camping spot these days for Simpson travellers, then on to Poeppel Corner. From here a faint and partly overgrown track once headed almost directly east (it’s practically impossible to find it now) to Eyre Creek and on to Big Red. From there it was an easy ride into Birdsville, just 14 days after they had left Bloods Creek Bore.

He was back in the Simpson in 2006 – he still can’t believe he passed a 12-year hiatus without visiting his beloved desert – helping support his daughter and her friends on a charity walk as they followed his walking route across the desert to raise money for the Breast Cancer Foundation.

In 2009 he was back in the Simpson again, raising a toast to a departed friend. The following year, he drove the vehicle back-up for his son, who walked across the desert in his footsteps.

Talking with Denis over the phone, I had to ask him about Big Red, the great dune he had named back on his first crossing of the desert, in 1977.

His reply was touched with feeling: “I had named it during that first crossing. In 1980, while sitting on one of its fiery domes, I was so inspired by the most magnificent sunset I had ever seen that I wrote a poem called Big Red, and for Overlander magazine [August 1982] I wrote a story called Three Tracks Across The Simpson, wherein I duly noted its position on the map.

“Promoted through the media, the mystery and romance of a big, red sand hill was born and over the past 40 years and 70-plus crossings, mostly solo, a ritual formed between that dune and me.

"A sunset whenever possible from Big Red was something not to be missed, for it was then that I could easily relive, in a most vivid form, my past journeys and scenery from its ever-changing landscape – I could truly be at one with the spirit of the desert.”

A lot of people have followed his example and sat on that mighty dune as the sun rose in the east or sank in the west, when the desert and that dune are at their most magical.

I hung the phone up reluctantly but I reckon if a good offer came along, Denis would drop everything, throw his DB Swag into the Cruiser and head out to the Simpson once more. He might live in south-east Queensland, but his heart – and the incredible legacy he created – is in the Simpson.

*First published in April 2016

COMMENTS