Ed Ordynski’s just spent all morning telling me how tough his life is, what with flinging a factory Mitsubishi RalliArt Lancer EVO VII between the trees and sliding around like a loon for his monthly stipend.

This feature was originally published in MOTOR’s May 2003 issue

It was easier in the EVO VI, he explained, because of a viscous coupling centre diff that squished “goop” through friction plates to spread the drive to the other diffs at either end of the car.

Still, the daintily-spoken South Australian almost won last year’s championship in one of these EVO VIIs until two uncharacteristic destructoes – both of which stemmed from weird drivetrain behaviour. The problem was eventually traced to a damaged wiring harness, but his confidence in the system is not yet fully restored.

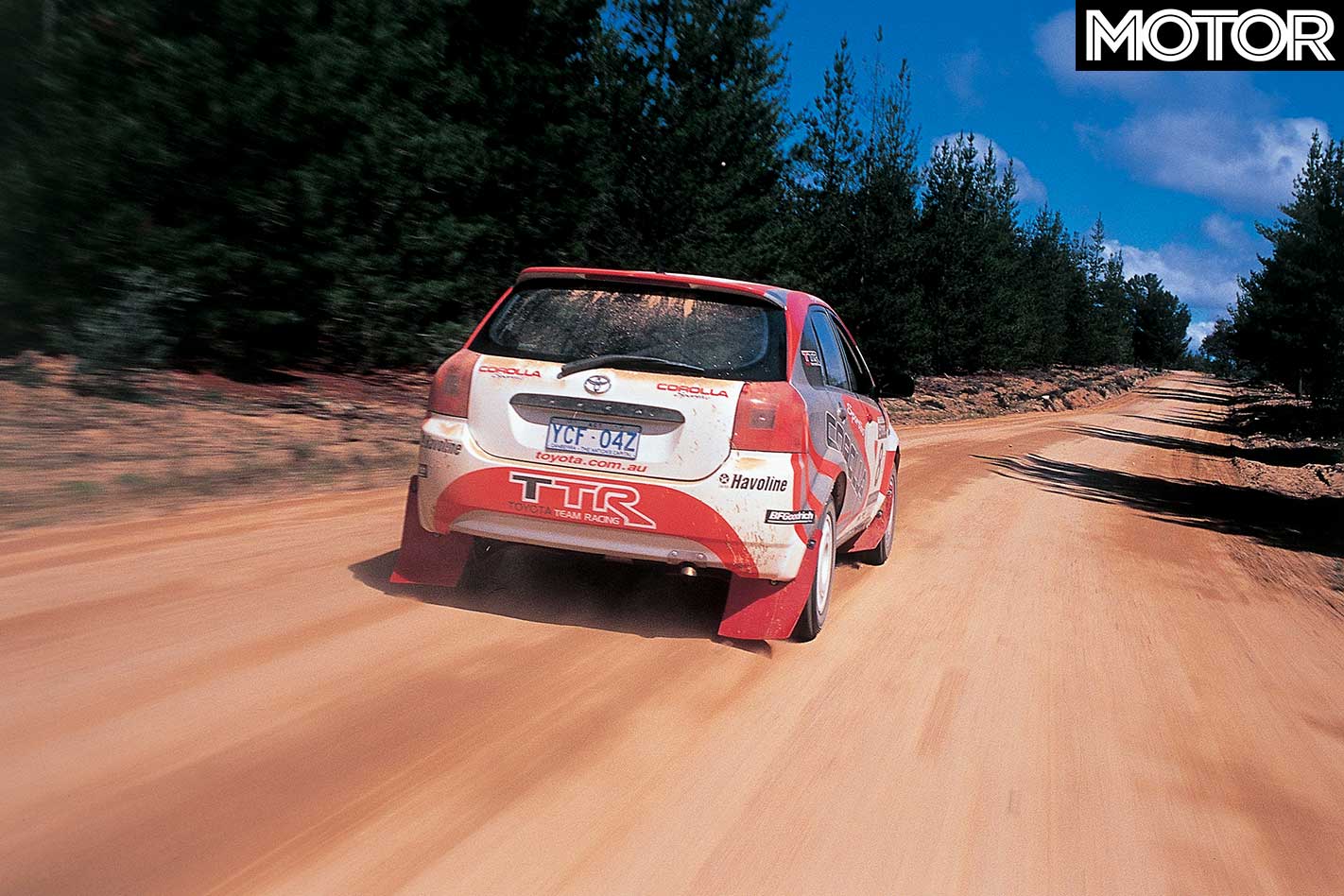

Not so Neal Bates. He wasn’t there last year. Purpose-built WRC cars (like his old Corolla) were banned after ’01, so he rested on the Bates date. He tried being uninterested in rallying, but that irked him.

Then he went to a couple of events and that irked him, too. After that he stayed home watched on telly, which irked his wife. Then the rally bods announced the Group N (P) class, to let manufacturers bung all-paw turbo running gear into more humble machinery. Bates jumped at the chance, and his crew worked furiously to mate Celica GT-FOUR drivetrain and suspension technology to the new Corolla body.

And so this is how we’re in the middle of a forest on a glorious Canberra morning with two genuine championship contenders to play with. It gets no better than this. For starters, no magazine anywhere has ever tested two leading national championship rivals back-to-back before the championship has even started. So what you’re getting is feedback these teams would normally kill for.

There are nerves, but not just from the MOTOR side of the fence. The first round is less than two weeks away, and the second Corolla (with the older car headed to Neal’s twin, sometime V8 Supercar driver, Rick) isn’t finished. Nor is the stress confined to Toyota. The RalliArt team had its two cars raring to go, until second driver Spencer Lowndes went tits up in testing five days before our drive.

Group N rally cars run quite a bit more boost than roadies. The EVO runs 1.4 bar – or 50 per cent more than standard. To offset the boost, they get choked back with 32 mm air inlet restrictors. The rules allow some freedom in gearboxes, which are universally five-speed with dog engagements that should last a full season without spannering.

We hit the Lancer first and, with the Ordynski tapeworms hard at it over the off-season, the boys need grease and shoehorns to make his thimble-sized seat fit a grown-up’s arse.

Other than that, his driving position’s spot on and the briefing is short and simple. Or, it could have been if I’d heard it. The Lancer turbocharger’s anti-lag system is incredibly brutal and raucous and it won’t idle worth a damn. It bangs and pops and I know I saw team boss Bob Reilly’s lips move, but…

First engages with the loud clunk of metal ingots banged together, but the clutch feels little different to a road EVO. Reverse is in the normal position, but I’m buggered if I can find it, so I surprise everybody by driving forward out of the bay.

Then it won’t play the game on part throttle. It’s just awful and I’m starting to wonder if I can drive it at all, particularly with Reilly’s warnings running around in my head.

Example: “It won’t turn if you’ve got brake on, because that just makes it act like a locked centre diff, because the boffins figure that’s the best way to stop. Come off the brake and it acts like a fully open version, because that’s best for turn in. There’s variations in between.”

Part of what I couldn’t hear covered the launch control. No matter, because the 5200 revs I’d figured on wasn’t far off the mark. Rip it off the line and, for anybody used to fast road cars, it’s not that special, really. It just spins all four wheels for about a second before whapping off into the distance with gravel cracking and clanging under the body.

Then you stop and think about it. It feels about as fast as a road EVO, but it’s on gravel, where it’s supposed to be really slippery. Except where the road car bogs down for lack of wheelspin, the rally car has you pulling second gear almost before you’ve got the clutch pedal all the way out the first time, with that flattish, muffled engine note much smoother now that it’s happy with the work. Then third takes a little longer, fourth longer still and you’re in fifth in an amazingly short space of time.

Even more amazing is that it’s doing it easily. Only later, in the Corolla, do I realize how tough it should have been, with the high crowns in the forest, different grip levels every few metres, constant changes in undulation and crown angle.

The EVO just punches up the road feeling like there’s nothing there. The Corolla demands constant attention, feeling far pointier, more rear drive and always wanting to slide the rear down the camber.

Neal’s thing also seems harder to get off the line. It’s much nicer to get it to the line to start with, though. His belts, for example, need no alteration and the thing’s quiet and idles nonchalantly. But whether it’s the way the diffs are set or the spring rates they’ve plumped for front-to-rear, I don’t know, it’s just harder to pull the trigger.

Launch it at the same revs as the EVO and it bogs down with either too much traction or not enough torque. Hard to say. It needs to be on or near the rev limiter to get its best, and then it still needs a touch of clutch slip.

In a straight sprint, the Corolla charges hard. Harder than the Lancer. It’s not until it gets to about 3000 revs that the Corolla gets spooled up, and until about 5000 it’s clearly the punchier of the two (though let’s not kid ourselves, you wouldn’t know who was playing games with the engine management computers for this sort of thing, would you?).

After 5000, it tails off fairly dramatically, where the Lancer keeps pulling to 6000 if you need it. Both cars have their torque peaks set quite low, so they’re usually quicker if they’re short-shifted.

Part of the difference may be gearing. Neal uses a Modena ’box and Ed’s is a Melbourne-built Holinger, but the Toyota uses the ratios homologated by Subaru’s Group N program.

Neither car really needs the clutch once in motion and, though both drivers use it on the way up anyway, only Ed uses it coming back. That explains why his is the only pedal box that allows for heel-toe downshifts.

Neal’s left foot is on exclusive braking duties, which leaves him free to pick up the throttle at whatever instant he likes. He needs to, as well, because the Corolla feels soggier than the Lancer once the MoTec tacho dips below about 2800 revs.

Then you get to the first corner, in either car, and you just can’t believe it. These things stop faster than English cricket hopes. The brakes are just phenomenal. They hurl you against the belts hard enough to bruise your collarbones and detach your retinas.

It’s an awesome, stunning display that totally defies the slipperiness of the surface under them. You couldn’t brake this late in a V8 Supercar, let alone a road car, and yet here you are on a surface grippier only than ice and mud.

While Ed’s uses simple twin-piston sliding front and single piston sliding rear arrangements (with the standard rotor size), Neal’s has the GT-FOUR’s two-piston rears and awesome four-piston front picks. He’s also had to machine the front rotors down to 300 mm all round, because the standard jobbies wouldn’t fit inside the wheels.

Like we found in other areas, while the cars are similar, they have some fairly clear differences in the detail. Neal’s brake pedal, for example, is easier to modulate while Ed’s is like a rock. But the real tricks are in the tyre technology. Ed’s Pirellis and Neal’s BF Goodrichs have been developed to bite into the road and tear it to shreds in an effort to turn kinetic energy into anything else.

You bring each car in straight under brakes (the most effective way on these tyres, so the boys say), but that’s only half the battle. You also have to have them pointed with just the right slip angle by the time you reach the turn-in point.

While the tyre boffins have conquered stopping on gravel, the laws of physics are yet to be overturned in the lateral grip department, so you have to use momentum and changes in angle to make them turn, rather than just slowing down and aiming for the apex.

Do this in Ed’s car and you can select your slip angle very early, aim the thing where you want it to start turning and stand on the brakes. The car will stop like you’ve hit something solid, but it’ll miraculously maintain exactly the slip-angle you’ve selected, all the way up to when you get off the picks.

Neal’s car is a different beast, adhering to more conventional thinking. Brake hard with the tail already out a bit and you can expect the tail to come out quite a bit more by the time you’ve finished. Little slides become quite big slides, but it’s very predictable. It’s most likely a set-up thing and it’s probably just something Neal’s just used to.

And then you come to the biggest differences in feel between these two cars. Between getting off the brakes, getting turned into a corner, getting the power down and getting it all straight again. Just the really important bits…

Where the Lancer’s anti-lag means it just leaps any time you get on it, the Corolla lags more. It’s got a bigger turbo (Neal would like to use a smaller one, but the GT-FOUR was homologated with this one, so it’s gotta stay) than either the Impreza or the Lancer and, off boost, it feels ordinary.

Out of slow corners it never quite feels like it’s got it going on properly, which is why you can hear Neal constantly, impatiently, tap-tap-tapping the throttle before he gets the Corolla to an apex.

Not the EVO. Wicked throttle response is its forte. It punches with genuine strength from as little as 1500 revs. It’s instant, too. Brush the throttle with a toe and it leaps instantly. Beautiful.

Turn in bite is defined differently in rally cars. The steering feel and weight isn’t dissimilar on either car and if anything, they’re both curiously slower in their racks than, say, an XR6T.

On tighter corners (second gear) you can use the Lancer’s throttle response to great effect from the nanosecond you’ve got the front to bite, then you can feel the centre diff’s brain working overtime to hurl you up the road as effectively as it can. And that’s very effectively indeed.

It has a lot of front diff emphasis in the way it delivers its drive out of corners. It will run wide, but it’ll generally run wide in languid four wheel drifts, everything scrabbling together to overcome the limitations of the surface.

To be fair, thousands of drivers across the world have been stumbling on demon EVO tweaks for years. It was, in VI form at least, developed to within an inch of its life. The Corolla is clearly less developed, worked on as it is by Neal’s hugely respected team and nobody else.

While Ed’s car is punching its way up the gravel, Neal’s feels more difficult for the driver to get set for the first half of a corner, walking on a knife’s edge of getting it right or wrong. The Lancer, by comparison, will happily perform if you get the approach within 10 per cent of spot on.

While that’s a driver accuracy issue and Neal and Rick are brilliant enough to not suffer, it’s on the way out of slower corners that the Corolla may struggle until its development is further advanced. It feels very rear-drive and wild opposite lock slides are part and parcel of the equation.

It’s fun and it looks good, but it doesn’t feel anything like as fast. They drift the car wide, wasting the engine’s work on greater slip angles than the Mitsubishi generally carries.

And the Lancer ride is hard compared to the Corollas, especially from the rear. Both of them carry suspensions so amazing you don’t feel any great impact from anything hard hitting underneath, and they’re both softer and more supple the harder you hit things (to a point, obviously), but the Corolla just soaks hits up like a sponge by comparison.

The Lancer also feels a bit more altogether, while the Corolla is clearly a one-off special. There are more things like pump whines and electric motor drives constantly on the go, and there’s a lot more by way of vibrations and harshness.

From the front, from the back, from the centre diff. It whines, it clunks, but it’s more driveable at light throttle openings. It’s the first of what Bates hopes will be many, and it’s clear they’ll just get better and better.

The Lancer’s more like a wound up road car and its chassis, remarkably, doesn’t feel as quite as rigid as the Corolla. It’s almost there, but not quite.

Of course, that’s at this speed. Push harder and it can all change, probably does. Rick reckoned the Corolla felt like it ran wide until he had a real go. Ed reckons the EVO is oversteery until you get quicker in it, then it’s an inherent understeerer. And that suits him just fine.

Right now, at this stage of its development, the Corolla doesn’t feel quite a match for the EVO. It’d go pretty close on uphill stages (if these engine outputs are indicative) and on faster stuff, but on the tighter stages, or places with looser surfaces, the Lancer feels like it just has its measure.

But later in the season, Ed, Spencer, Cody, Dean and Possum better watch out. If the Corolla’s this quick out of the box, it’s only going to get faster.

Then Mr Ordynski might realize his life was never really that tough after all.

No Subaru?

So by now you’ve picked the obvious: there’s no Subaru in here. We tried, but the old Possum’s got a bit on his plate this year, what with a tilt at the Gp N World crown on top of defending his ARC title – and fending off teammates Dean Herridge and five-time Gp N champ Cody Croker. The short and sweet of it is that he didn’t want to risk one of the blue cars. Can’t really blame him for that.

5 Winningest ARC facts

Champs

1 – Possum Bourne (7), Subaru ’96 – ’02 2 – Ross Dunkerton (5), Datsun ’75 – ’77, ’79, ’83 3 – Neal Bates (3), Toyota ’93 – ’95 4 – Greg Carr (3), Ford ’78, Alfa Romeo ’87, Lancia ’89 5 – Colin Bond (3), Holden ’71 – ’72, ’74

Manufacturers

1 – Daihatsu, win some bets here, boys! (6), ’91 – ’96 2 – Subaru, lose some bets here, (4), ’97 – ’98, ’00 – ’01 3 – Holden, is there nothing it can’t do? (4), ’71 – ’74 4 – Nissan, not the immortal privateer Dattos, (3), ’75 – ’77 5 – Mitsubishi, plus six Group N crowns, (2), ’90, ’99

Porsche Boxster

D-I-Y rally car Don’t want to rally a Lancer or WRX? Build your own

So this whole rally caper looks like a bit of fun. Except, if your name rhymes with “Mates” and you live in Canberra, you’re probably not allowed to drive an EVO Lancer or one of those bloody quick blue things. So you build your own, don’t you?

Neal Bates and Possum Bourne used to have the only World Rally Cars in the ARC, but when the championship switched to production cars, it killed ’em off at a stroke.

In Group N, you’re allowed to take a production car and make some rally-style tweaks. For example, the gearbox internals are free, provided you stick to homologated ratios. Brakes are standard, but you can use any pads. Engine hardware is standard, but management is free. Shocks and springs are free. You’re allowed flexibility with the diffs, provided the housings are the same.

Of course, all this is contingent upon your favoured carmaker actually having an all-paw, turbo in the first place. Subaru did, so Possum kept driving. Toyota didn’t.

The new Group N (P) rules let Toyota back into its favoured game. The rules, designed to open the sport up to manufacturers without WRX or EVO-style road cars, is parity driven and gives three options. Neal’s Team Toyota Racing took the hardest of the three Gp N (P) options, which is to scour the Toyota parts bin to find a 2.0-litre engine, turbocharger and all-wheel drive system, and shove it all in one car.

The 3S-GTE engine and the running gear from the Celica GT-FOUR is still sold in the Caldina in Japan, so it was easier than it might have been. Still, it took about 1400 hours to build.

Option two is to take a family 2.0-litre four pot, turbo it, then mate it to EVO or WRX running gear. That could be a bit difficult at the interface.

The third option, and a beauty for the likes of Proton or Daewoo, is to simply take WRX or EVO running gear and bung it in your own car.

Fast Facts

| u00a0 | 2003u00a0Toyota Corolla Sportivo (rally spec) | 2003u00a0Mitsubishi Lancer EVO VIIu00a0(rally spec) |

| BODY | five-door hatch | four-door sedan |

| DRIVE | all-wheel drive | all-wheel drive |

| ENGINE | 2.0-litre, 16-valve DOHC turbo four, 32 mm air inlet restrictor | 2.0-litre, 16-valve DOHC turbo four, 32 mm air inlet restrictor |

| BORE/STROKE | 86.0mm x 86.0mm | 85.0mm x 88.0mm |

| COMPRESSION | 8.6:1 | 8.8:1 |

| POWER | 186kW @ 5000rpm | 205kW @ 5500rpm (approx.) |

| TORQUE | 430Nm @ 4000rpm | 431Nm @ 3200-3500rpm |

| WEIGHT | 1385kg | 1392kg |

| POWER/WEIGHT | 137kW/tonne | 147kW/tonne |

| TRANSMISSION | Modena five-speed manual | Holinger five-speed manual |

| SUSPENSION (f) | MacPherson struts, coils, dampers, anti-roll bar | MacPherson struts, coil springs, anti-roll bar |

| SUSPENSION (r) | MacPherson struts, coils dampers, anti-roll bar | semi-trailing arms, coil springs, anti-roll bar |

| L/W/H | 4175/1695/1470mm | 4455/1770/1450mm |

| WHEELBASE | 2600mm | 2625mm |

| TRACKS | 1520mm (f); 1510mm (r) | 1520mm (f); 1507mm (r) |

| BRAKES (f) | 300mm grooved, ventilated discs, four-piston calipers | 297mm ventilated discs, two-piston sliding calipers |

| BRAKES (r) | 300mm ventilated discs, twin-piston calipers | 297mm ventilated discs, single-piston sliding calipers |

| FUEL | 60 litre Kevlar bladder, PULP | 80 litre Kevlar bladder, PULP |

| WHEELS | 15 x 7.0-inch (f & r), alloy | 15 x 6.5-inch (f & r), alloy |

| TYRE SIZES | 205/65 15 (f & r) | 205/65 15 (f & r) |

| TYRE | BF Goodrich | Pirelli |

| PRICE | $150,000 | $180,000 |