It would be easy to dismiss the claim that BMW built the E30 M3 as a race car first and then worked backwards as glib marketing speak, but even a cursory glance at its racing CV lends it credibility.

After all, the E30 M3 won the 1987 WTCC, 1987 and 1989 DTM, 1988 and 1991 BTCC, 1987 ATCC, 1987-90 French Supertouring titles and the Italian Superturismo series in 1987 and 1989-91. And despite not being conceived as a rally car, the E30 also won the 1987 Tour de Corse (the last rear-drive car to win a WRC rally).

Chassis changes included a quicker steering rack (19.6:1 to the standard car’s 20.5:1), three times more castor, stronger wheel bearings, wider tracks, revised shocks with shorter, stiffer springs, a thicker (19mm) rear anti-roll bar and the front anti-roll bar being linked to the struts. Electronically-adjustable dampers with three settings became an option in 1988.

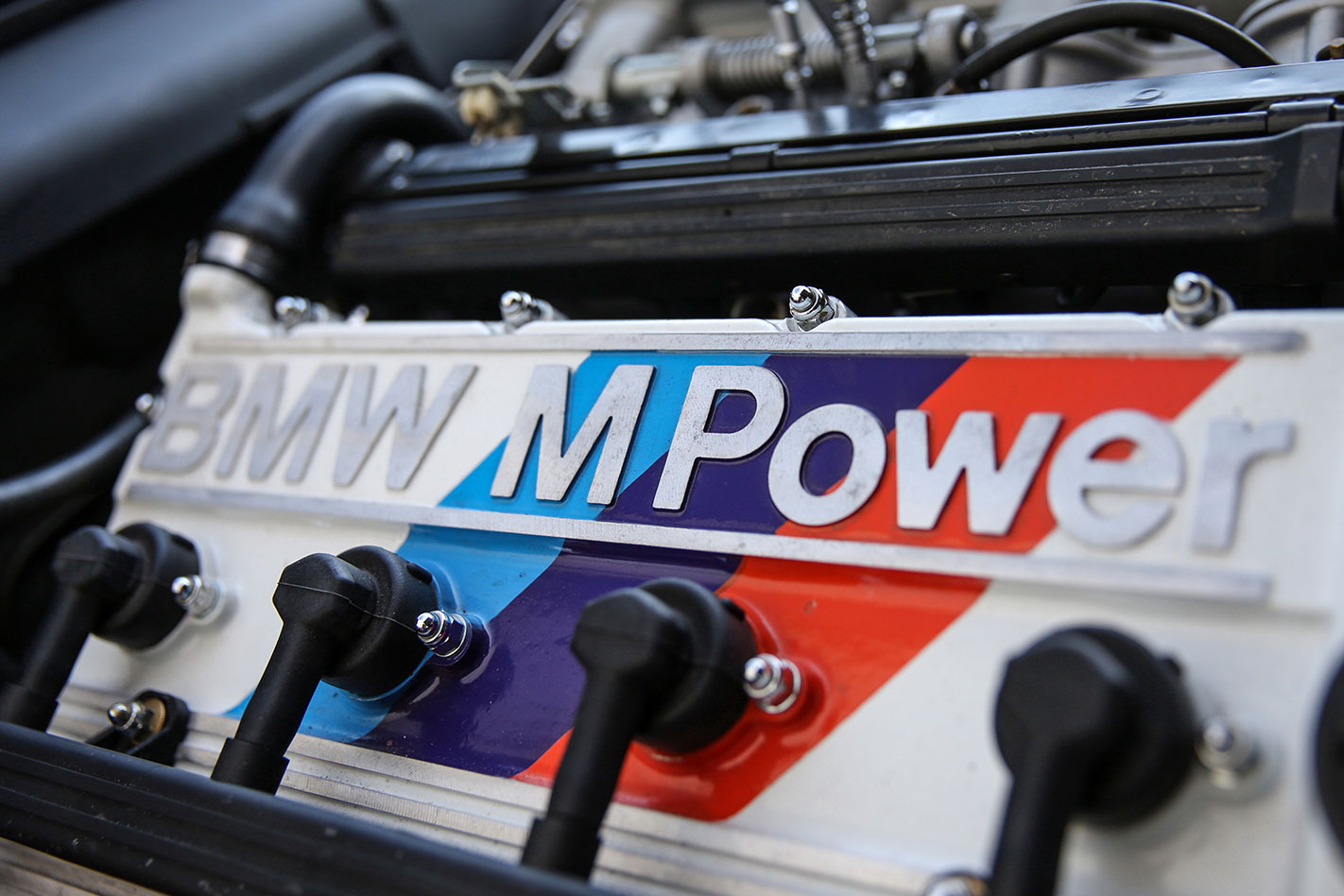

A revised engine, introduced in September 1989, altered outputs to 158kW/230Nm. All models came with a five-speed manual gearbox and limited-slip differential.

The first Evolution, introduced in February 1987, is not named as such, as it merely added a revised cylinder head and the 505 cars built are not individually numbered.

More BMW M2s allocated for Australia … again

Finally, aero tweaks included a deeper front airdam with brake ducts replacing the foglights and an additional lip spoiler at the rear. Each car is individually numbered out of 500, though according to production records 501 were built… Last but not least were 600 Sport Evolutions (see breakout).

Five ultimate BMW M3s part 5: M4 GTS

The familiar driving position makes it easier to grapple with the dog-leg gearbox, as muscle memory keeps getting in the way on downchanges. The shift itself is long but it’s quite easy to heel-toe, though the driving position is a little long-armed as the steering wheel – heavily offset to the left – isn’t adjustable for reach.

Sticky Dunlops make Rob’s car feel a little over-gripped, but the chassis balance is tremendous and the steering a highlight, quite slow in its gearing but not at all ponderous, and the way it weights up naturally under load without unduly increasing effort is delicious.