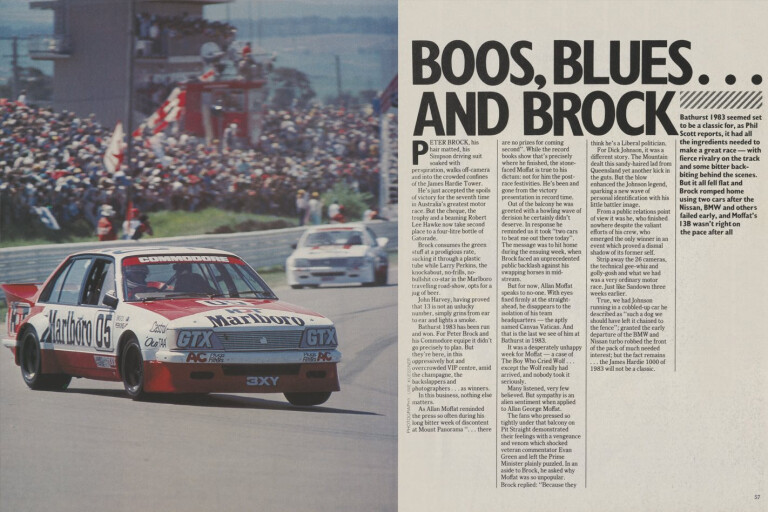

PETER BROCK, his hair matted, his Simpson driving suit soaked with perspiration, walks off-camera and into the crowded confines of the James Hardie Tower.

He's just accepted the spoils of victory for the seventh time in Australia's greatest motor race. But the cheque, the trophy and a beaming Robert Lee Hawke now take second place to a four-litre bottle of Gatorade.

Brock consumes the green stuff at a prodigious rate, sucking it through a plastic tube while Larry Perkins, the knockabout, no-frills, no-bullshit co-star in the Marlboro travelling road-show, opts for a jug of beer.

John Harvey, having proved that 13 is not an unlucky number, simply grins from ear to ear and lights a smoke.

Bathurst 1983 has been run and won. For Peter Brock and his Commodore equipe it didn't go precisely to plan. But they're here, in this oppressively hot and overcrowded VIP entre, amid the champagne, the backslappers and photographers … as winners.

In this business, nothing else matters. As Allan Moffat reminded the press so often during his long bitter week of discontent at Mount Panorama " . .. there are no prizes for coming second". While the record books show that's precisely where he finished, the stone-faced Moffat is true to his dictum: not for him the postrace festivities. He's been and gone from the victory presentation in record time.

Out of the balcony he was greeted with a howling wave of derision he certainly didn't deserve. In response he reminded us it took "two cars to beat me out there today". The message was to hit home during the ensuing week, when Brock faced an unprecedented public backlash against his swapping horses in midstream.

But for now, Allan Moffat speaks to no-one. With eyes fixed firmly at the straight-ahead, he disappears to the isolation of his team headquarters - the aptly named Canvas Vatican. And that is the last we see of him at Bathurst in 1983.

It was a desperately unhappy week for Moffat - a case of The Boy Who Cried Wolf … except the Wolf really had arrived, and nobody took it seriously.

Many listened, very few believed. But sympathy is an alien sentiment when applied to Allan George Moffat.

The fans who pressed so tightly under that balcony on Pit Straight demonstrated their feelings with a vengeance and venom which shocked veteran commentator Evan Green and left the Prime Minister plainly puzzled. In an aside to Brock, he asked why Moffat was so unpopular. Brock replied: "Because they think he's a Liberal politician.”

For Dick Johnson, it was a different story. The Mountain dealt this sandy-haired lad from Queensland yet another kick in the guts. But the blow enhanced the Johnson legend, sparking a new wave of personal identification with his little battler image. From a public relations point of view it was he, who finished nowhere despite the valiant efforts of his crew, who emerged the only winner in an event which proved a dismal shadow of its former self: Strip away the 26 cameras, the technical gee-whiz and golly-gosh and what we had ·was a very ordinary motor race. Just like Sandown three weeks earlier.

True, we had Johnson running in a cobbled-up car he described as "such a dog we should have left it chained to the fence"; granted the early departure of the BMW and Nissan turbo robbed the front of the pack of much needed interest; but the fact remains ... the James Hardie 1000 of 1983 will not be a classic.

The rule makers cocked it up. And while it is easy to be critical with the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, the men who control motorsport – our motorsport - have some soul searching to do: the Bathurst mystique may not survive too many repeats of 1983.

This then is the story of a controversial week at the foot of Mount Panorama. It started out as the story of Peter Brock's Bathurst - and in a sense it still is - but to ignore the politics, the innuendo, the tension and the personal misfortune of the other leading characters would be to shut out the essence of the week that was. It began on Tuesday. On a note which set the scene for things to come.

Kevin Bartlett, one of the most senior drivers in the sport, walked into Canvas Vatican for an unscheduled audience with Pope Allan, the pistol toting guards having not yet taken up their posts.

As a rather nonplussed Bartlett later described it, he was told to wait outside where Mr Moffat would "make himself available in a few moments". This from a colleague of 20 years standing. So much for sport and the camaraderie of the Mountain ...

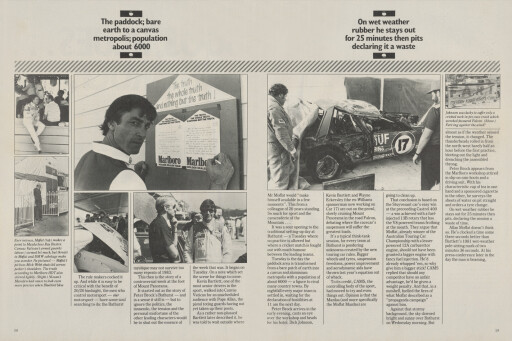

It was a sour opening to the traditional setting-up day at Bathurst - a Tuesday where no practice is allowed but where a cricket match is fought out with much humour between the leading teams. Tuesday is the day the paddock area is transformed from a bare patch of earth into a canvas and aluminium metropolis with a population of about 6000 - a figure to rival many country towns. By nightfall every major team is settled in, waiting for the declaration of hostilities at 11 am the next day.

Peter Brock arrives in the early evening, casts an eye over the workshop and heads for his hotel. Dick Johnson, Kevin Bartlett and Wayne Eckersley (the ex-Williams spannerman now working on Car 17) are out on the prowl, slowly cruising Mount Panorama in the road Falcon, debating where the race car's suspension will suffer the greatest loads.

It's a typical think-tank session, for every team at Bathurst is pondering unknowns created by the new touring car rules. Bigger wheels and tyres, suspension freedoms, power improvement and aerodynamic aids have thrown last year's equation out of whack.

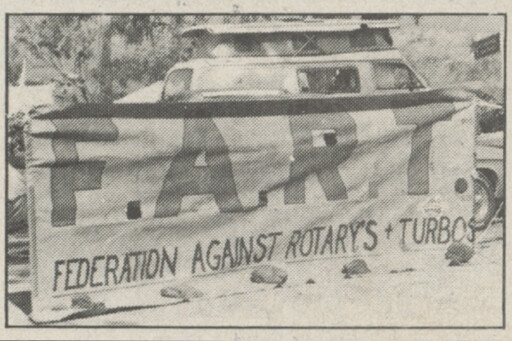

To its credit, CAMS, the controlling body of the sport, had moved to try and even things out. Opinion is that the Mazdas (and more specifically the Moffat Mazdas) are going to clean up. That conclusion is based on the Stuyvesant car's easy win at the preceding Castrol400 - a win achieved with a fuel-injected 13B rotary that has the V8 powered teams frothing at the mouth. They argue that Moffat, already winner of the Australian Touring Car Championship with a lesser powered 12A carburettor engine, should not have been granted a bigger engine with fancy fuel injection. He’d already whupped 'em, so why give him a bigger stick? CAMS replied that should any competitor have an unfair advantage, he'd be given a weight penalty. And that, in a nutshell, fuelled the fires of what Moffat described as a "propaganda campaign" against him.

Against that stormy background, the sky dawned bright and sunny over Bathurst on Wednesday morning. But almost as if the weather sensed the tension, it changed. The thunderheads rolled in from the north-west barely half an hour before the first practice, blotting out the light and drenching the assembled throng.

Peter Brock appears from the Marlboro workshop attired in slip-on rain-boots and a driving suit. With his characteristic cup of tea in one hand and a sponsored cigarette in the other, he surveys the sheets of water on pit straight and orders a tyre change.

On wet weather rubber he stays out for 25 minutes then pits, declaring the session a waste of time.

Allan Moffat doesn't think so. He's clocked a time some three seconds better than Bartlett's 1981 wet-weather pole-sitting mark of two minutes 36 seconds. At his press conference later in the day the man is beaming, obviously well pleased. And why not?

If you listen to Commodore punter Allan Grice, the Stuyvesant car has the 1983 James Hardie shot to bits: "We went into the Cutting side-by-side and as soon as we straightened up, he just out-accelerated me. By the time we got to the top of the hill I was out of his slip. He was gone!

"You could have reached in and dead set knocked me out, because that's one spot on the track where you'd reckon V8 grunt would count…”

So the battle lines are drawn. The animosity grows stronger, a despondent Grice refers to Moffat as "that Canadian member of the New York Yacht Club".

Peter Brock meanwhile has other problems - embarrassing problems. You see his pit counter has been painted with the very famous slogan of a rival cigarette company - and it will be in full view of the television cameras come Sunday.

Taking matters into his own hands, Brock plasters a dozen Marlboro stickers over the offending logo, pausing to chat over developments during practice. He's a polished performer, this man they call Peter Perfect, totally relaxed and easy-going - a stark contrast to the brooding presence of Moffat.

As the sun breaks through we talk: "I was worried about Moffat before I left Melbourne - I didn't have to get to Bathurst to know his car went ... I saw it at Sandown.

"Up here he's virtually got a one-minute advantage with fuel injection, because fuel injection is all about saving a pit stop. You wait until Sunday."

Brock' s analysis is totally plausible - or so it seems. And his thoughts on the current state of play are equally worthy of note. Of Dick Johnson he says: "He's more likely, because of the stress on the machinery, to have a problem. Keep in mind his car has never completed 163 laps at Bathurst."

On the relativity between himself and Moffat: "I still think we can win, if we get our act together totally and don't have any hitches, we can j-u-s-t win.

"But we must remember we waltzed away with the race last year and CAMS are doing everything in their power to make sure it doesn't happen again; my concern is that they've gone too far."

Despite the rain - and the fog which closes the circuit for 20 minutes during the afternoon - the Brock team is in good spirits as the drivers sit down for post practice de-brief. They're a diverse lot. Brock, with the articulate nice guy image which almost makes you forget the tales of his hellraising youth; John Harvey, a more reserved, quietly spoken character; Larry Perkins, the mother hen of the team, given to calling a spade a spade in no uncertain terms. As well as co-driving, he's responsible for the mechanical preparation of the cars and organising the crew of mechanics, tyre and fuel men. Then there's Phil Brock alias “Split-pin” - younger brother of Peter - tackling the Mountain for the first time in five years.

They gather in the canvas privacy of their compound with tea and cigarettes. Perkins is assertive, firing questions at the others. It appears the wheel balance is bad on Brock's car and he wants the gearshift angled closer to him.

The 05 car is locking a front brake at the top of the Mountain which prompts a discussion on braking distances at the end of Conrod. Harvey's seatbelts are coming undone and Perkins reckons his seat is angled too far forward. He reckons you need "a peg up your arse to locate it properly."

Then a lengthy discussion on, believe it or not, the inside diameters of drink tubes. It's mundane stuff, no scoops here. But the practice sessions today really haven't told the team very much. All they've done is bed in engines, drivelines and brakes in preparation for Sunday.

And tomorrow? "We've got to get down to some serious chassis tuning" says Brock.

WEATHER FINE, track good is the news on Thursday morning and the crews have some catching up to do. Brock is out early but obviously doesn't like the way the Commodore is handling.

He orders the front springs changed because "around here you've got to compromise between setting it up for the straights and the bumps while still retaining some sort of roadholding through corners ... That's what I'm trying to do - trying to make the car feel nice."

He's chasing balance too, for with big bags on the back the Commodore's front-end grip is found wanting. So far the team is using race compound Avon tyres on Momo rims, but with some extra chassis tweaks in the afternoon, Brock switches to soft compound Dunlops. The difference is immediate and apparent.

His best morning time of 17.7 drops to a sizzling 15.8 - nearly two seconds inside the 1982 pole-time. Brock is happy and quips to Perkins: "I nearly tipped her on its roof up there, LP. There was just so much grip, my inside wheel must've been three feet off the deck!"

But in motor racing there is point … and counterpoint.

At his daily press conference - dubbed the Claytons Conference - Allan Moffat tells us: "Brock shouldn't be hard to beat at all – providing you've got an F111 parked on top of Conrod. There's no race at the moment. The best I might squeeze out of the little Mazda is an 18.5!"

Gone is the beaming countenance and the punchy repartee of yesterday. In its place Moffat carries a sombre mantle. "Brock has done a 15.8 today," he lectures. "I've done a 20.9 - that's five seconds I have to find overnight. If you have any suggestions I'll be waiting for you outside."

And still the woe-is-me outpouring continues: "I've done a year's work since I last sat in this room and I'm basically bitching about the same thing I did a year ago. We were a long way from our opposition then, and we're still that far away."

Then the bombshell: " I've been so far out-homologated it's unbelievable."

But why such a turnaround in just 24 hours? "My hour in the sun was shortlived yesterday, wasn't it? I couldn't let the euphoria go, it comes so infrequently I had to grab it while I could".

Many listened, very few believed. Moffat was foxing they said: take it all with a grain of salt. What we didn't know was that the fuel injection system he lobbied so hard to get was causing high drama inside the Vatican City. But that is another story, for another day.

For now, we return to the MHDT compound where Peter Brock imparts the wisdom of 15 jousts with the Mountain to a rookie - Adelaide motoring writer Bob Jennings. "The entrance to McPhillamy, Castrol ... that area down to Forest Elbow, that's where all the time is mate. On the rest of it, you're not going to lose much. If you have a real go through there, compared to doing it nice and neat but still brisk, there's bloody two seconds."

Brock is sitting in the back of the team caravan, driving suit rolled down to the waist, the ever present cup of tea in his hand.

It's the first time we've had a chance to talk about anything other than immediate news. Brock responds with practised panache to every question.

How does he approach the week of Bathurst, the culmination of six months’ work? "I try and have a very normal, relaxed week - a bit of sitting around, a bit of chat and a bit of teev, read and a novel, that sort of thing. I don't like roaring around and seeing too many jokers, dropping in here and there for a social chat.

"As far as I'm concerned I try and make it like a normal week at home - relaxed, with just the team around. That's good, because if you think of something you can go and find someone and say 'hey, I just thought of something, why don't we try this and this'. At Bathurst you can't afford to lose impetus, even when you're relaxing. You've got to eat, sleep and drink the race ... for the whole week."

And what about the press, the constant stream of microphones, cameras and the same tired old questions?

"Sometimes it bothers me, sure. But it gets down to a personality thing really; there are some blokes you can cop and others you can't."

Does he notice any build up in tension - what the drivers call putting on a race face – as Sunday gets closer?

"I try and not change too much," is all he says.

It's time to go. Larry Perkins has finished directing traffic in the workshop. He calls a driver's de-brief but there are no problems. The MHDT is operating with the precision of a Swiss watch. And tomorrow is the day the cards must be laid face up on the table. For Friday is qualifying day at the Mountain.

THE BIG question at Mount Panorama on the last day of September, 1983 is the strategy of Team Tense - the Peter Stuyvesant Mazda outfit.

Expert opinion says Allan Moffat will run dead (on race rubber and full tanks) to just squeeze himself into the top 10. To run hard and post a good time would be bad for his image and could attract the handicappers for 1984. Or so the experts said.

But the qualifying skirmish begins with Brock and Harvey first out of the flying lap and running in very close company. A tow for two perhaps?

Brock opens with a 17.7, closes with a 15.5, then puts 05 away. He's a bit tighter this morning is Peter Perfect. He talks, but not in the same flowing, easy way. He sits in a director's chair at the back of the garage, with Porsche sunglasses shading his eyes.

"Quite frankly, you're risking your car out there. These people are on line and off line and all you can do is hope to God they stay where they are. I just put in one quick one to qualify us for the race."

Brock's reference to "these people" includes some of the 23 rookies and, one suspects, quite a few of experienced, but still once-a-year pedallers out there. His prophecy is fulfilled minutes later. Grice slams the fence at The Cutting after an altercation with a Falcon.

With an ice pack clasped to his head, Grice vents his spleen at what he sees as some very poor wheelcraft on the part of the Ford driver: "I got such an overlap on him that I could look across and see his hands - it was my corner. Then I saw him turn down and I thought, oh shit, and he came straight across into me. The car went into the fence and put the right front wheel into the firewall".

There are other casualties too - reinforcing Leo Geoghegan's theory that there are 30 drivers in this country who are totally capable, another 30 reasonably capable, and the rest ... have never gone so fast in their lives.

However the Grice incident, the spectacular demise of Jim Keogh and half a dozen other biffs and bingles, are overshadowed by the non-performance of Allan Moffat.

He can do no better than a 20.3 - well adrift of the leaders. In fact well adrift of his 1982 qualifying time of 18.89 set in a 12A car.

The latter only serves to reinforce the foxing strategy. After all, you don't spend 12 months on chassis and brakes development, fit a bigger engine and fuel injection ... then go slower.

Moffat himself, after securing a lowly 14th grid position - two behind junior partner Gregg Hansford in a 12A car - makes his feelings on the matter quite clear:

Q: Is anything left in your car?

A: Probably another 12 months with the CAMS homologation committee.

Q: Why are you slower than last year? Is there a mechanical gremlin involved?

A: Not one we can put our finger on. What you're looking at is a propaganda campaign against the Mazda organised by the Holden/Ford/BMW group to cover up their own mechanical subterfuge.

And then some quite definitive statements on the state of play at Vatican City: "Every time we go out we put our best foot forward. I never go out not trying to win. If Brock lapped me on lap 39 last year, he'll lap me on lap 29 this year. It would take a miracle for us to win".

Now in my experience Allan Moffat is not given to telling outright fibs. He'll colour an argument, exaggerate a point, omit to tell you certain things, but he pulls up short of calling black, white. He had problems, that much was obvious. Many listened, very few believed. Those who believed sought to find out why, to try and skirt the glib Moffat phraseology and the veil of secrecy which surrounds everything he does.

The real story goes something like this: the Stuyvesant team received 13B injected engines fresh off the dyno and ready to run.

So on Wednesday Allan Moffat practised with his winning Sandown 13B and it performed well, remembering it was wet, and therefore slower than normal.

But when the crunch came on Thursday - and again on Friday when a supposedly screamer engine went in for qualifying - the injection system refused to co-operate.

It was running too lean at the top of the Mountain and too rich down the bottom. And it wouldn't rev out, a crucial factor with the rotary motor.

According to a reliably informed source, the Japs had dynoed the engines and set the injection mixture for prevailing conditions - in Japan. Sandown is a flat circuit, not far above sea level. The 13B won in a canter. Bathurst is 670m above sea level and the circuit itself rises and falls 190 m in a lap. Moffat was in heaps of strife. Chief mechanic Mick Webb confided to one highly qualified source that the Japs were using the Stuyvesant team as unknowing guinea pigs, that the factory had used injection only during qualifying sessions in the past, that to his knowledge it had never actually been raced.

The no-race theory still doesn't quite gel, but Mr Moffat is not pleased, and the foxing theory gathers strength.

Peter Brock lends weight to it: "Moffat must know he can run 20s all day with a full tank, because that's what he was doing out there today.

"I'll be watching for him around lap 130 when he'll move up and win by the least possible distance. Remember, he's still got a year's racing ahead of him and he doesn't want to be handicapped out of existence. Mate, he's simply the best politician there is".

Howard Marsden, who's been around a long time is equally emphatic: "Oh, he'll win allright, he won't let them get away, Moffat will be there all day, just out of sight, running a race that will look as though he j-u-s-t makes it. But he won't do it by taking fewer fuel stops, he tried that last year and overcooked it. He won't do it again".

On that question Moffat is at his bristling best: ''Asking me what I want to do with my fuel economy is like asking a gorgeous lady how old she is. Basically, it's none of your business.''

And so Allan Moffat, as he has done so very often in the past, has stamped his personality very firmly on proceedings. What other driver has qualified 14th and monopolised media attention with such intrigue? Like him or lump him, Moffat is good for the business of motor racing.

With Friday despatched, there is an opportunity to sit down with Brock and Perkins and talk. Brock looks to be at unbackable odds to snare pole position, although he says he is worried about Dick Johnson and anyway, qualifying and Hardies Heroes are a sideshow - of secondary importance to winning the race: "Personally I couldn't care less about having pole because of the position on the track or that it's going to help me win," he says. "But 10 grand's 10 grand and there's a helluva lot of media coverage, which helps your sponsors."

The MHDT is bang on schedule, working to a plan devised by Perkins many months ago. They're still chasing a slight chassis imbalance and Car 25 isn't yet a carbon copy of Brock' s 05, but by tomorrow night both problems will be solved.

For now, there remains some public relations duties downtown. There's a function to attend, words to be said and some waltzing with the festival queen. Brock wrinkles his nose, mutters something about it not quite matching the racing driver's macho image and organises "something decent" for Larry Perkins to wear. It will be an early night however, for tomorrow brings with it Hardies Heroes.

WITH MOFFAT out of the top 10 and the remarkable Bob Morris in, interest centres on four cars - the Brock Commodore, the Nissan Turbo of Fury, the BMW 625Csi of Jim Richards and Dick Johnson's Falcon.

Allan Grice must be considered behind the eightball, for he's been chasing a handling problem all week and yesterday's accident must take its toll. It's all fairly predictable stuff until Dick Johnson has his run. The pit row crowd follows it on television. Those whose attention wanders are snapped back by Mike Raymond's urgent commentary: "He's hit the fence ... and he's off!"

The monitors go black and Jill Johnson collapses over her timing equipment, in tears of grief and desperation. It is a moment she has secretly dreaded. Two months earlier she told me: "The danger doesn't really enter your mind - which probably sounds silly. When you think about it you know it can happen – to anybody - but you just concentrate on other things".

What she experiences during those frightful seconds until Evan Green brings the good news - news she at first can't comprehend – brings this whole business back into sharp focus. These guys are putting their lives on the line out there - something too often overshadowed by politics, razzamatazz and pree-zen-tayshun.

Nobody standing near the Johnson pit can avoid sharing that feeling of shock – and loss. But the plucky Johnson emerges remarkably unscathed from an accident that could quite easily have claimed his life.

An hour after it happened, I am ushered into the privacy of his caravan to hear the first account from the man himself. He is sitting quietly, smoking a cigarette and dressed in the team uniform. Apart from a nick in the centre of his forehead, he shows no other signs of the encounter - outwardly at least.

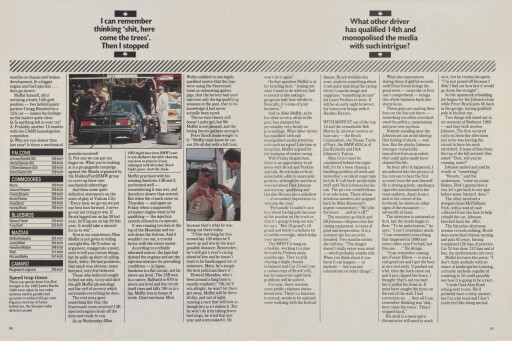

The interview is awkward at first, but the words begin to flow: "To be quite honest," he says, "I can't remember much.

"I can remember everything that happened in 1980 and every other race I've had, but this one ... " He shrugs.

"I can remember coming into Forest Elbow- it was a real good run and I got the boot in nice and early. It pushed out a bit, then the back came out and it just clipped the fence. I thought 'that's not too bad', but it pulled the front in. It must have caught the tyres on the end of the wall. I had correction on ... then all I can remember thinking was 'shit, here come the trees'. Then I stopped hard."

His neck is a mess and a chiropractor will need to work on it, but he retains his spirit: "I'm just pissed off because I didn't find out how fast it would go down the straight".

So the mammoth rebuilding job begins for the Johnson team while Peter Brock puts 05 back in the garage, having grabbed pole in his first run.

Two things will stand out in my memory of Bathurst 1983 - and they both involve Johnson. The first occurred early on Saturday afternoon just as he was leaving the circuit to have his neck stretched. A team of fans from the top of the hill arrived. One asked "Dick, will you be running, mate?" Johnson smiled and said he would, in "something". "Beauty," said the spokesman, "come on youse blokes, Dick's gunna have a run, let's get back to our spot before some bastard does.''

The other involved a delegate from McPhillamy Park, with a wad of cash collected from the fans to help rebuild the car. Johnson knocked back the offer.

The Saturday afternoon session reveals nothing. Brock does some final chassis turning and puts 05 away, having completed 120 laps of practice. Car 25 has done 132 laps and at last, the preliminaries are over.

Moffat lectures the press: "I don't think anybody with an ounce of kindergarten training, certainly anybody capable of counting to 10 could possibly see how it is going to be a race.

"I wish I had Alan Bond sitting next to me. He'd probably have a witty answer, but I'm a bit tired and I don't really feel like doing mental repartee with you."

And so the main event. Johnson makes it after a rebuild on the Andrew Harris Falcon, which had the fans six and seven deep outside his workshop all night. The atmosphere was hushed, almost religious, as they peered intently through windows, angled for a glimpse through the doors.

Brock, as expected, gets away with a flourish and opens up an early lead. In the space of two laps, most of his opposition evaporates. Fury is gone with a blown gearbox, Richards pits with metal filings clogging the injectors - sabotage, says Frank Gardner - and Moffat pulls up to ninth.

By lap 10 anyone with an ounce of kindergarten training can see there is no race. Brock will simply devastate the field.

But then the engine in 05 detonates like a hand grenade and the black-eyed Marlboro man is back in the pits with a contingency plan.

The papers are already signed for he and Perkins to take over car 25. It's perfectly legal, but something the "viewers at home" can't quite comprehend.

Brock says: "We'll get the second car up there and cracking, but it's difficult to see how the race will pan out. I think Moffat is capable of staying with us. I'll just have to try and re-establish a gap".

So, on lap 20 Harvey gets the IN signal and 32 seconds after he pits, Brock roars back out in Car 25. As he later said, it felt "wonky".

"It wasn't horrendous, but after a couple of laps I thought to myself, this car's not going to finish. It was vibrating when I left the pits, pulling to the right and the brake balance was a bit dodgy."

But Peter Perfect drove a percentage race and his pit crew backed him magnificently. His next three stops, two of which involved driver changes, were done in 31 seconds, 32 seconds and finally, 37 seconds.

Moffat led briefly, but was let down by tardy pit stops. The final margin was 163 seconds, or a second per lap. Harvey contended the Marlboro team made up 60 seconds alone with slicker pit work. But we shall never know what the margin might have been as Brock eased off, content to keep Moffat in sight. And Moffat also conserved his car.

Brock rattled off a couple of quick ones towards the finish, but the race had been won between laps 21 and 57. The rest was a formality. Just as it has been at Bathurst for too many years now.

How long is it since we've had a close finish? Brock won it by a lap in '78, six laps in '79, a lap in 1980 - we had the 740 km race in 1981 - and a further on lap margin in 1982.

But Bathurst is Bathurst and the fans will continue the annual pilgrimage. Perhaps.

As Allan Grice put it so succinctly: "I think this event will always have it. It's like the Melbourne Cup. It doesn't matter if a horse gets out and wins by 20 lengths, it's still the Melbourne Cup."

Dick Johnson's bitter luck continued after the race had run its course. Fifty kilometres out of Bathurst, a towball sheared on a borrowed truck driven by a team member. The rig, with the remains of Car 17 on the trailer, rolled and was destroyed.

COMMENTS