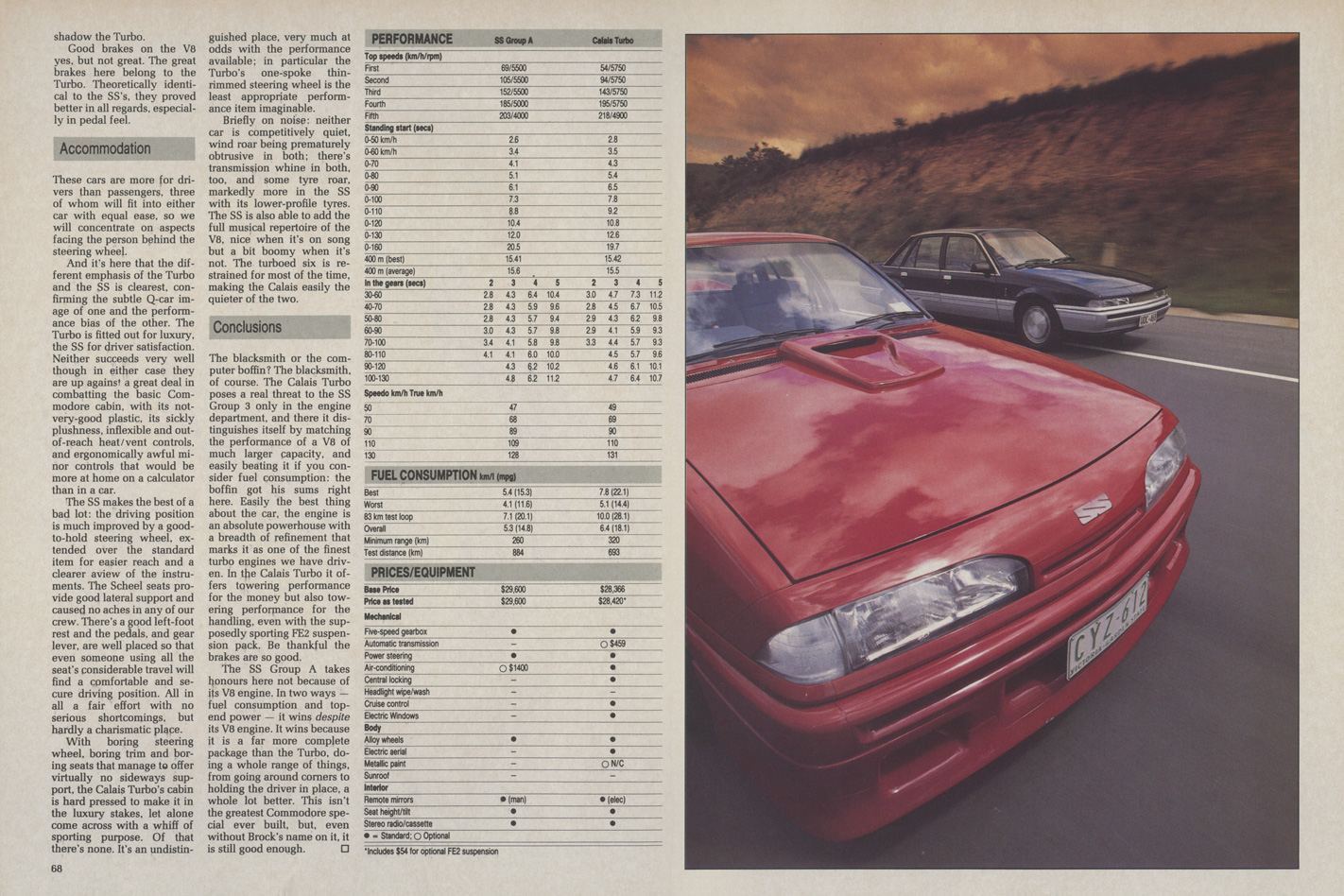

THE ANSWER you are busting to know is that eight pots of iron does beat six pots of high-tech – by one one-hundredth of a second. It’s there on our stopwatch printout: Commodore SS Group A 15.41 secs, Calais Turbo 15.42 secs over the standard 400m test course.

You wouldn’t read about it. It’s meaningless. Of course. The margin could be 10 secs in either car’s favour and still be as meaningless as figures always are when taken out of context. Still, as a peg on which to hang this comparison the 400 m times are as good as anything else because they establish a pecking order which – to our great surprise, and that of a lot of other people – persists through most aspects of this comparison.

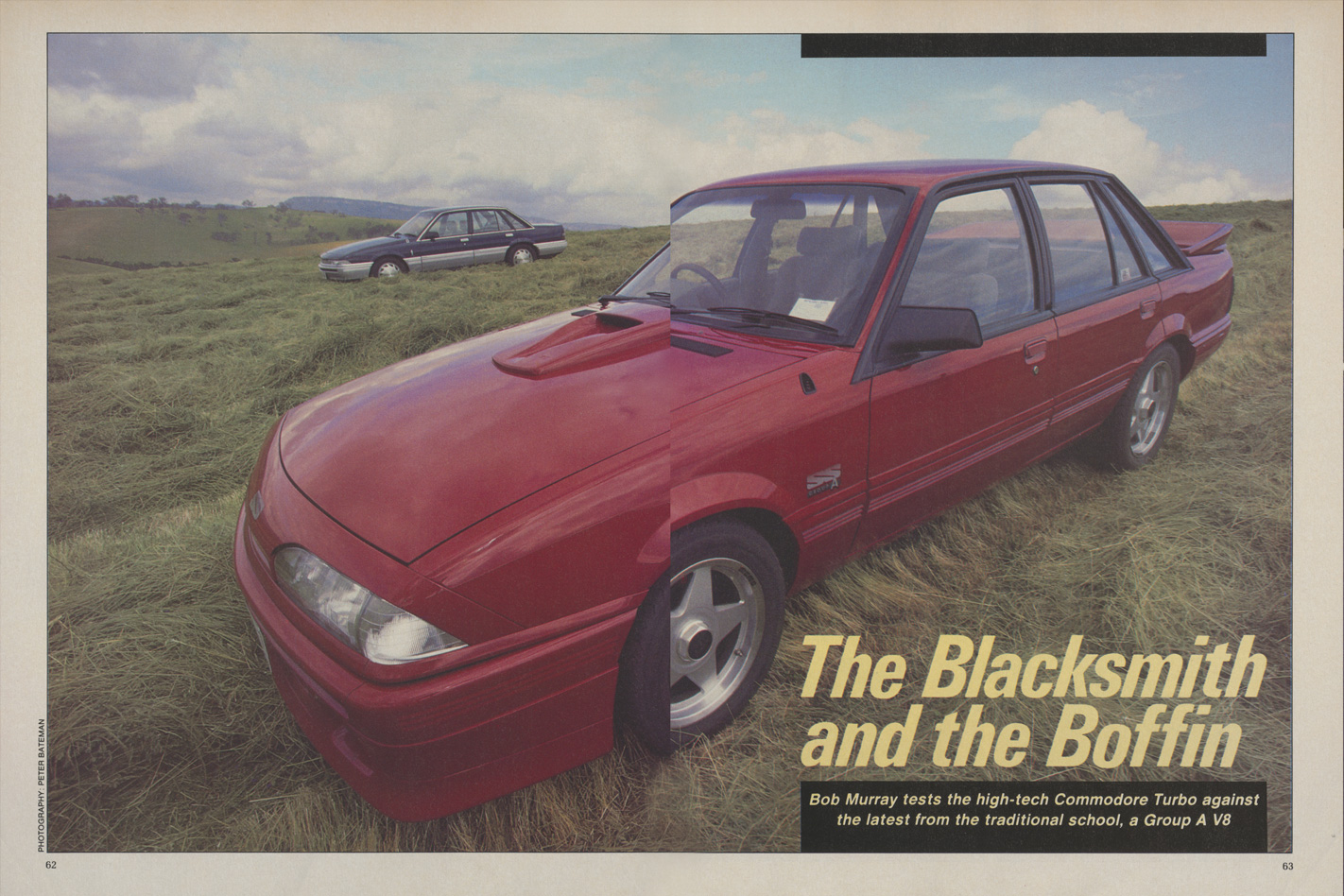

It’s also a comparison of Peter Brock’s methods and GMH’s methods, of a racetrack spinoff and a luxury freeway flier. The cars may both be Commodores underneath, the badges may both say Holden, but to the customers at least this plainly is as crucial a comparison as if the cars had been made by deadly rivals.

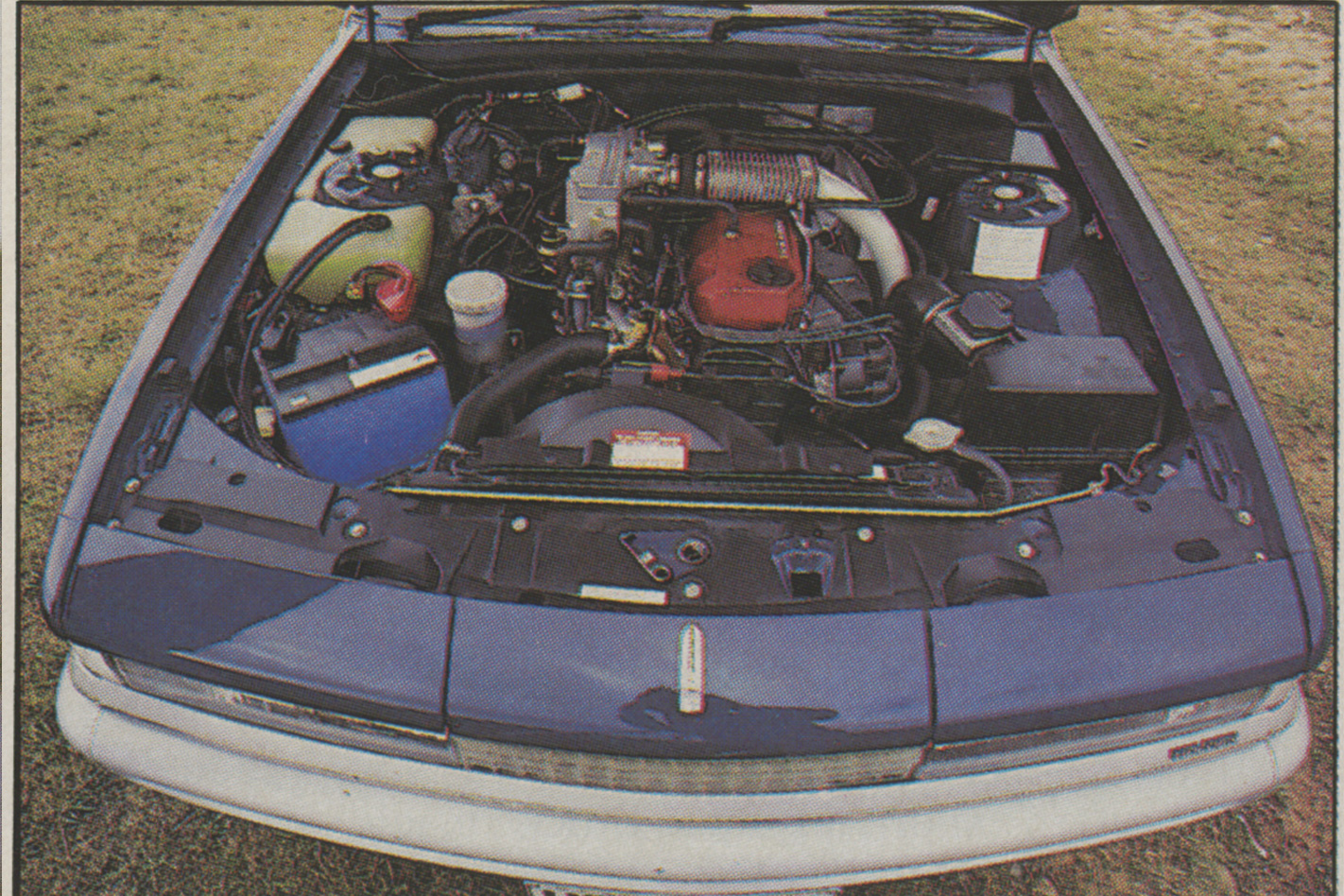

Central to these cars are their engines. One is a 137 kW V8, latest unleaded fuel version of a powerplant which can trace its origins back to the late 1960s. The other is a 150 kW turbo six, a Nissan engine embodying the latest technology that Japan has to offer. Both engines give their respective models ground-covering ability close to that of a light plane: that, perhaps, was expected.

We also expected – wrongly, as it turned out – that the engines would provide the telling differences between the cars. The discovery that they don’t, in most ways at least, speaks greatly in praise of both units: on GM and the Holden Dealer Team for updating so successfully such a crude lump, and on Nissan for coming up with a high-tech recipe that provides a successful alternative to the tradition of the strong V8.

Ground covering ability of a light plane? Hopefully there’s someone out there who can use these cars. Fast and long, as they have been designed to be used. Many SSs and Turbos, we know, will never be required to give their full potential, operating more as objects of enjoyment and satisfaction than as high-speed driving tools. Restrictions on using a fast car are a fact of life but one that hardly detracts from ownership: the range of pleasures to be had in driving a powerful car, sensibly and with good judgment, is generally more than merely sitting all day on a freeway at 200 km/h.

For this comparison, then, we will be looking for something more than just the right numbers on the stopwatch, which by themselves are no guarantee of anything except speeding tickets.

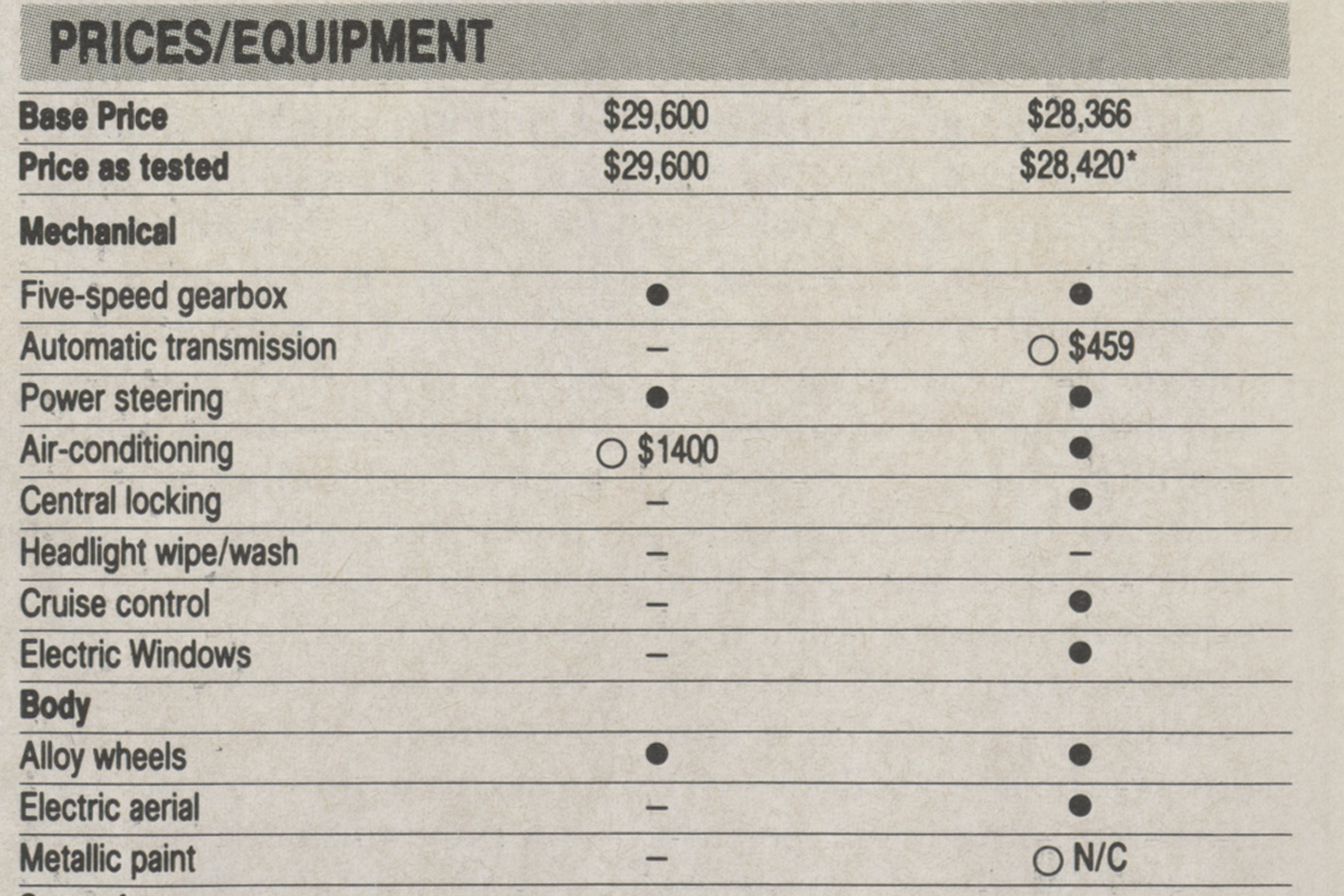

The picture isn’t all rosy, of course: status, trim and build quality are all firmly Holden, and thus about as far away from a Mercedes or BMW as it is possible to get. The Calais Turbo, at $28,420 with FE2 uprated suspension, fares better here than the SS, which is built around a Commodore SL and thus comes without the Calais’ luxury trimmings- electric windows, cruise control, central locking, electric aerial, airconditioning, electric mirrors. For a car costing well over a grand more than the Calais some of these omissions jar a little.

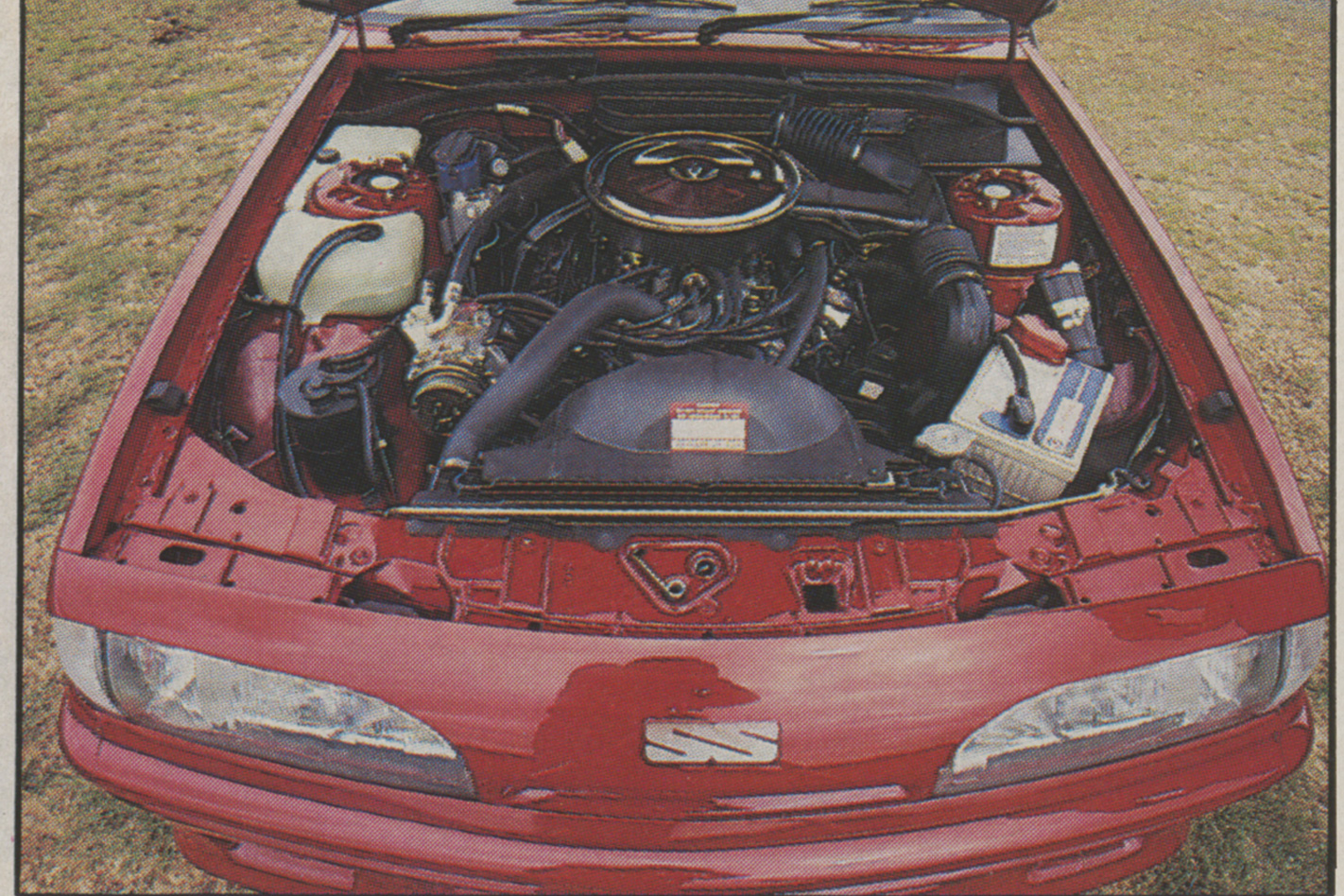

What you do get in the SS is a more overtly sporting package, in impact the equal of anything to have rolled out of HDT’s door but perhaps rather less appealing than most. The latest nose treatment doesn’t mate anywhere near as well with the usual package of body add-ons, specially when they are as over-the-top as the bonnet bulge and the enormous rear wing. All-over red paint, Momo steering wheel and Scheel sports seats get the sports message across just in case you miss the very tacky edition number on the dashboard. The Calais Turbo is the ultimate Q car in comparison.

Automatic transmission is the most significant option for the Calais, a feature which in all probability makes it the fastest four-door auto sold in this country. Air and an anti-theft system are GMH’s only listed options for the SS, though as usual HDT, which supplies GM with some parts (US gearbox, clutch housing, suspension components) and which acts as final assembler, has a deal of flexibility in fitting extra items.

Foremost here is the A-plus pack at $1800 fitted. Peter Brock, whose name doesn’t appear on the SS Group A, is reticent to spell out what you get in this pack, but it does include the energy polariser, Brock’s extra which he – and, he says, several owners – swear by but which, for its less than readily understandable nature, has been the subject of some controversy. Brock claims the press trivialises the polariser because it doesn’t understand it. GMH’s statement on the polariser is to the point: “We see no technical merit in the polariser and therefore can’t endorse its use.”

Despite this. Brock says GMH has left the door open for its fitment, and that in due course he will be making an official presentation to GMH on the polariser’s merits, something he says he has not so far done. He is adamant that eventually all 500 of the SS Group As HDT is building (at 21 a day at the time of writing) will be fitted with the device, though at the time we spoke to him all were to GMH spec, ie sans polarisers.

Brock says he is quite happy to put his name to the A-plus car but that his moniker won’t be appearing on the standard SS. He says – incorrectly in our view – that this has always been the case with previous SS models made to base GMH spec. The faint impression of a Peter Brock-style signature on the test car’s Morna steering wheel, whose appearance suggested it had been rubbed partly off, was in fact a mistake. “The Morna wheel is made in Italy and this is a poor Italian copy of my signature.”

Engines/performance

Whether they’re aligned or not, the molecules under the bonnet of each car go to make up a powerful whole, in the case of both engines. But how different they are: five-litre pushrod V8 drinking through a Rochester four-barrel carburettor, versus a three-litre overhead cam turbocharged six with up-to-the-minute fuel injection and computerised engine management.

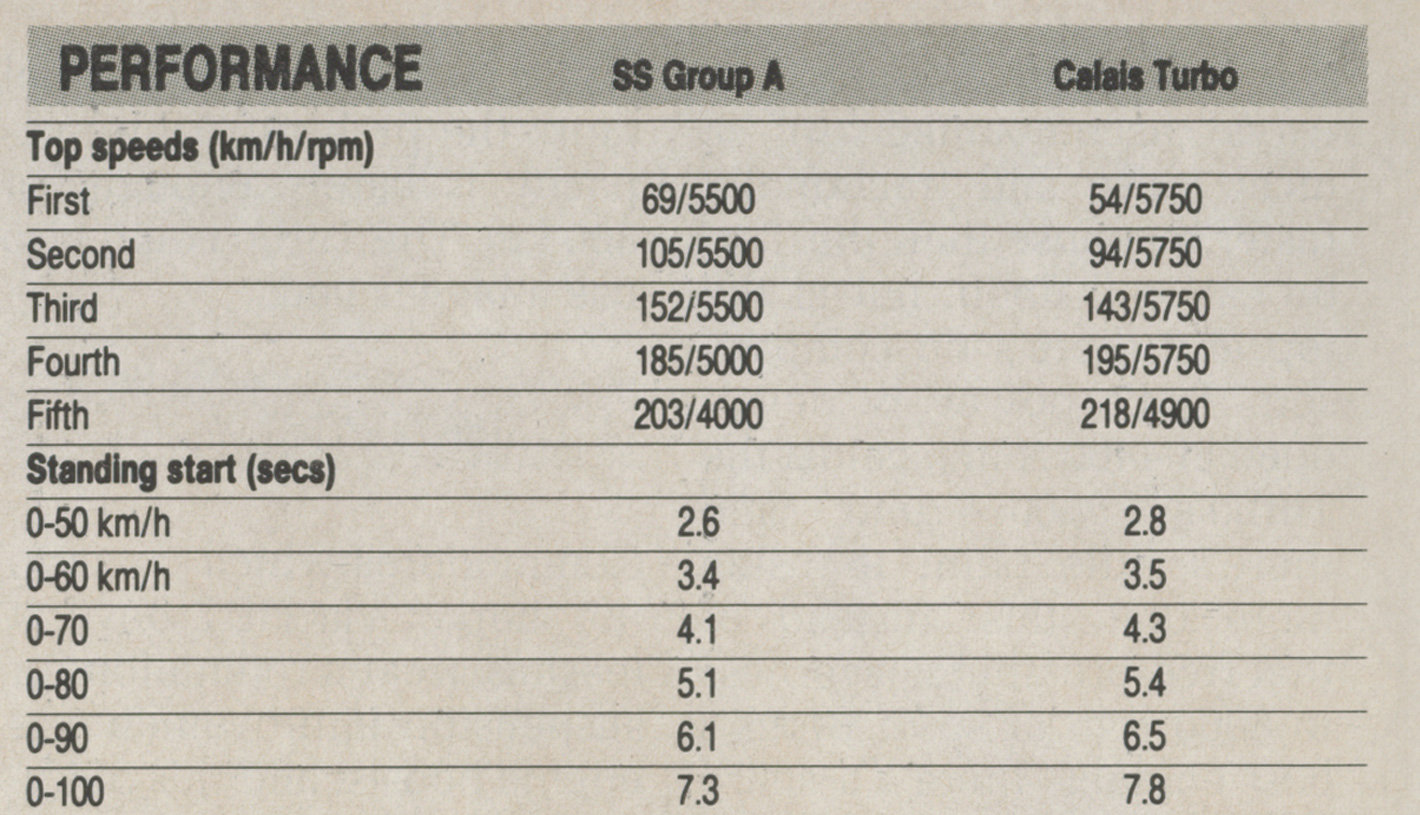

A 10 percent power advantage is claimed by the Turbo, a 17 percent torque advantage goes to the SS. Against the Calais’ greater weight is the SS’s taller gearing, so on all counts the contest should be close.

And so it proves: despite the odd hundredth of a second, in a straight line the cars are neck and neck in real terms, both in outright acceleration and in-gears flexibility. To keep things in perspective, both are uncommonly quick, reaching 100 km/h in less than eight seconds, 160 km/h in around 20, topping 200 km/h flat out (the Turbo by the greater margin) and, perhaps most importantly, offering excellent pick-up in the high gears. An average of our 30 km/h incremental times for fifth gear shows both cars to display identical response, 10.1 seconds. In fourth the averages are 6.25 secs for the Turbo, 6.0 for the SS, whose figures generally fall within a narrower band than the Calais’, though let it be said now the Turbo is never out of its performance depth, as one would expect from an engine with more puff than capacity.

It is as much at home trundling through traffic in fifth as maintaining a loping highway stride, and in both cases has ample lag-free response for any manoeuvre that calls for an instant burst of speed. The gear ratios themselves are well judged but the gearchange is poor: the lever has a long, rather vague travel and is prone both to notchiness and noisy complaints from the synchromesh on fast changes. The clutch’s sharp, short take-up doesn’t improve matters.

The Turbo’s engine note is far from unpleasant, apart from the Nissan speciality of a nasty drone when you lift off to change gears at high rpm, but it would be a person of little style who said they preferred it to the burbling masculinity of the SS’s V8. This is an integral part of any Australian sporting sedan and in this latest SS it’s there in all its glory even though, as any comparison will show, overall performance levels are well down on previous leaded-engine Commodore specials. Given it was either this V8 or no V8 at all we’re not complaining.

Does this detract from the SS’s sporting credentials? A little, yes, though in overall terms the V8 is still more sporting – and certainly less anonymous – than the Turbo. Besides, there are other compensations the Turbo can’t match. The SS’s American Borg Warner gearbox, with HDT-only ratios culminating in a mammoth 50.7 km/h per 1000 rpm fifth , has a delightfully chunky and positive change, and the clutch, too – significantly firmer than the Turbo’s – is much more satisfying.

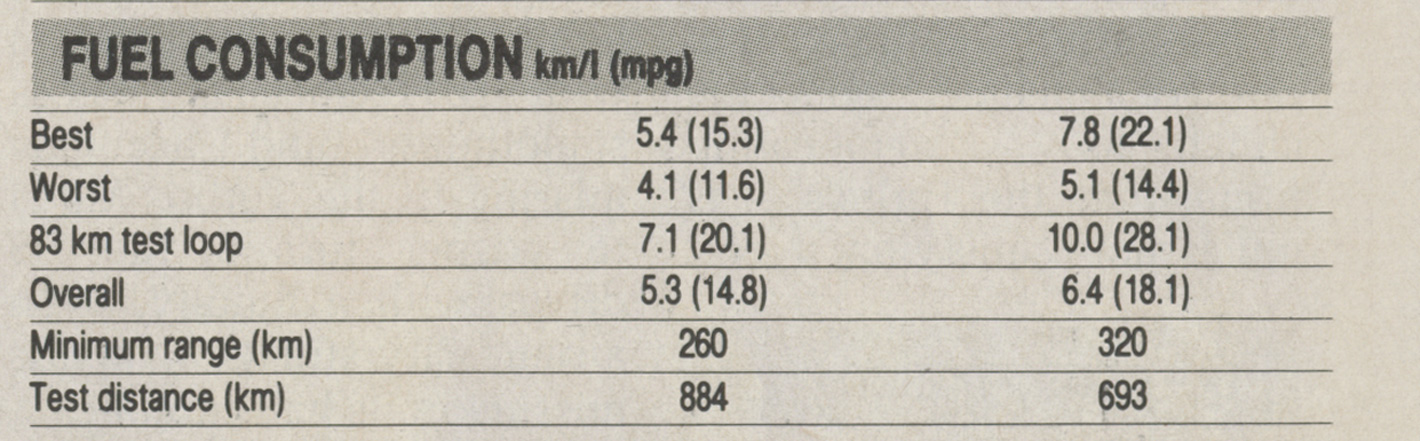

More plaudits for the Nissan engine here: given the performance available in this size of car, an overall 6.4 km/l (18.1 mpg) is creditable.

When used to the full the blown six is no miser but it still manages to maintain a usefully large advantage over the heavy-drinking SS. That buffer is shown to best advantage in our fuel loop figure, a mixture of non-high performance motoring where the Turbo’s excellent 10.0 km /l (28.1 mpg) is 40 percent better than the SS manages.

On the road

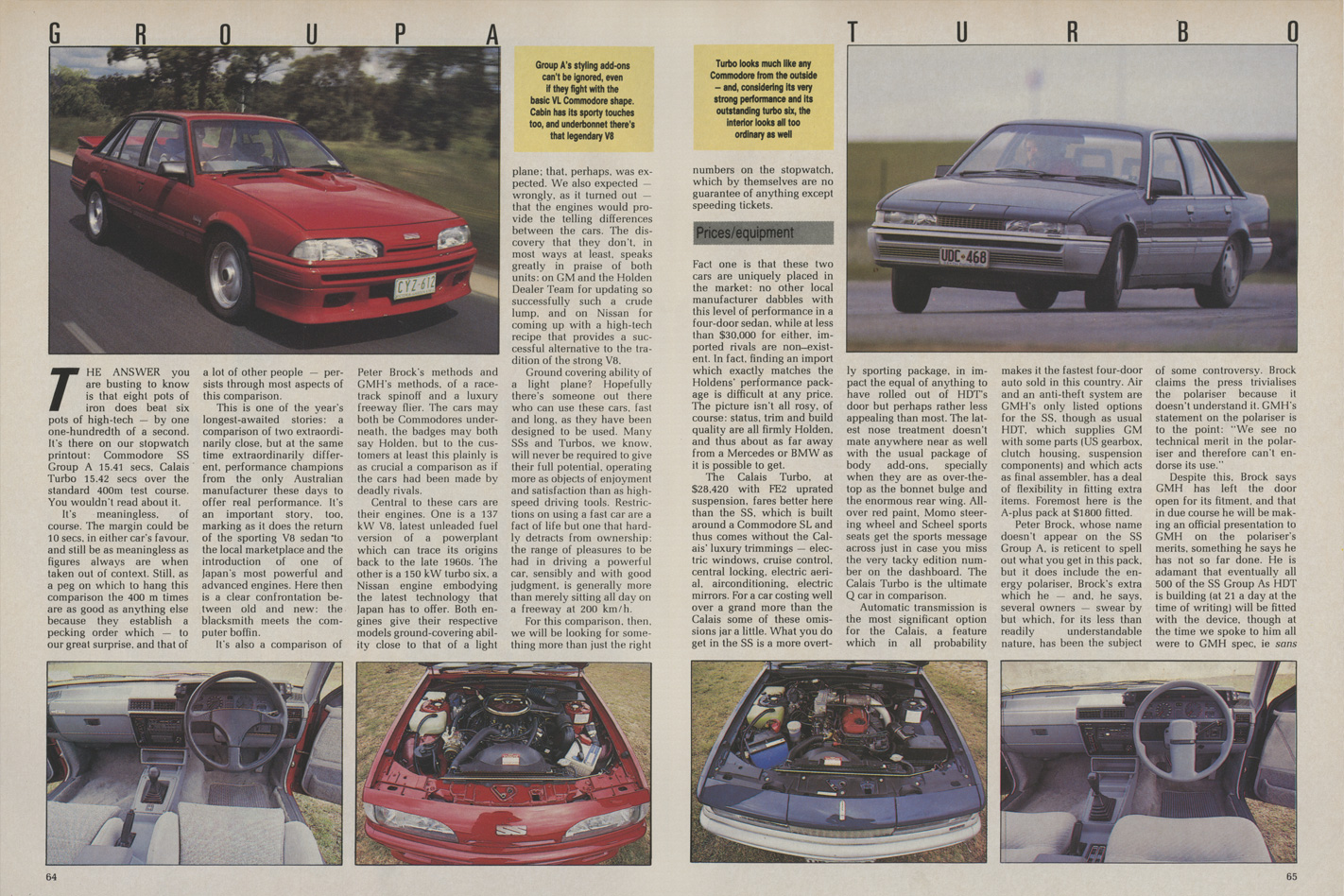

Commodores which come to the market via HDT have at least as great a reputation for suspension improvements as engine boosts, and this SS reinforces that reputation superbly. At a time when GMH has been struggling with the VL Commodore’s suspension, the SS comes as a welcome reminder of just how well the old girl can handle.

The SS is overall more capable, just plain nicer to drive, than the Turbo. Not only in an out and out sporting sense either: true, at the track the V8 was instantly quicker than the Turbo, displaying an effortlessness and predictability that made the Turbo appear a real handful, but the advantage is real in everyday driving too.

The SS’s ride is firmer, reacting sharply (and noisily) to sudden small irregularities such as cat’s eyes, but the car rides flatly, with superb damping control, and many will find it is actually preferable, even over bad city streets, to the Turbo. There is more compliance and pothole-absorbing travel here, and less tyre and suspension noise, but overall the ride is unsettled without ever smoothing out at speed or approaching the SS’s levels of damping and body control.

Both cars use Bridgestone tyres and they are a good choice, for we have no complaints with either car’s roadholding.

Again, though, it’s the SS that makes best use of available grip, with a much more neutral attitude and far less body roll. The back end will come wide more easily with a sudden throttle lift-off, but it’s a controllable oversteer whereas that same condition in the Turbo is likely to result in a series of lurching fishtail slides.

On public roads, within its limits, the Turbo emerges as a competent but uninspiring handler, less than ideally accurate but flat of body and always with an understeer bias, even with power off. Overall it’s far less poised than the SS. That car, on the track, merely extended its normal characteristics without adding bad manners (the odd spinning inside rear wheel apart, indicating that, for serious punters, a more limited limited-slip diff may be desirable). It was obedient and drama-free, a combination which, when allied to burbling V8, snappy gearshift and good brakes, was enough to completely over-shadow the Turbo.

Good brakes on the VB, yes, but not great. The great brakes here belong to the Turbo. Theoretically identical to the SS’s, they proved better in all regards, especially in pedal feel.

Accommodation

These cars are more for drivers than passengers, three of whom will fit into either car with equal ease, so we will concentrate on aspects facing the person behind the steering wheel.

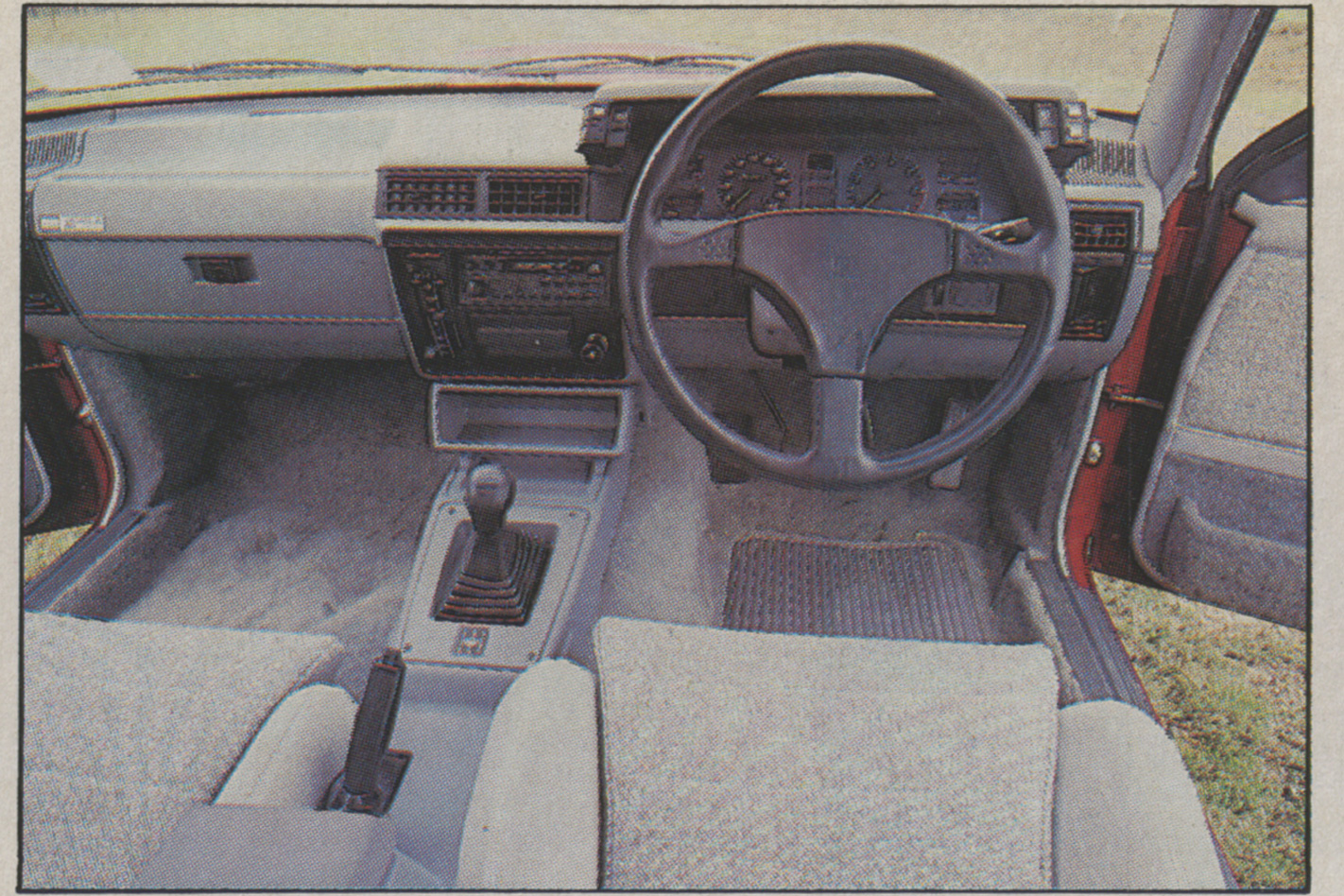

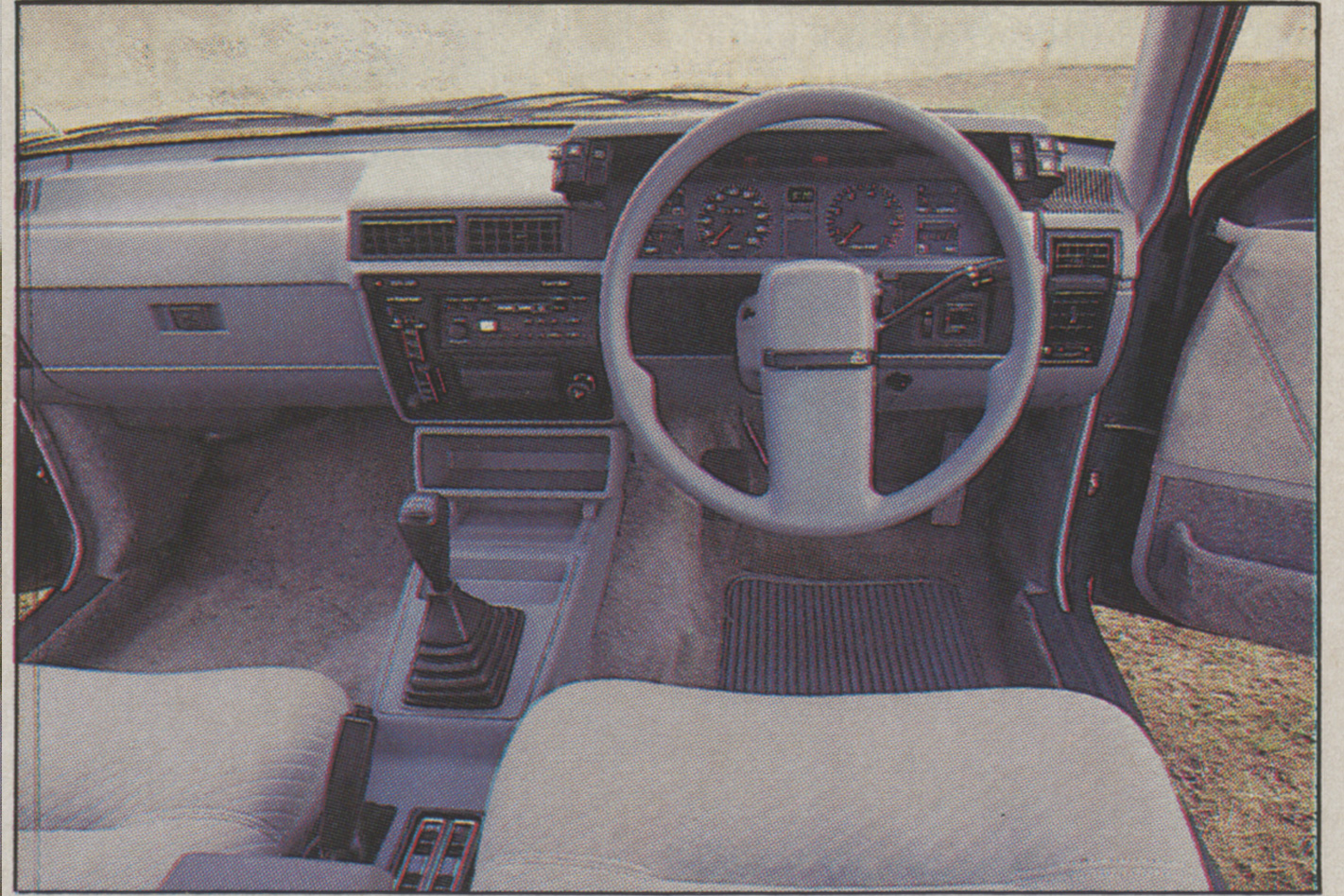

And it’s here that the different emphasis of the Turbo and the SS is clearest, confirming the subtle Q-car image of one and the performance bias of the other. The Turbo is fitted out for luxury, the SS for driver satisfaction. Neither succeeds very well though in either case they are up against a great deal in combatting the basic Commodore cabin, with its not-very-good plastic, its sickly plushness, inflexible and out-of-reach heat/vent controls, and ergonomically awful minor controls that would be more at home on a calculator than in a car.

With boring steering wheel, boring trim and boring seats that manage to offer virtually no sideways support, the Calais Turbo’s cabin is hard pressed to make it in the luxury stakes, let alone come across with a whiff of sporting purpose. Of that there’s none. It’s an undistinguished place, very much at odds with the performance available; in particular the Turbo’s one-spoke thin-rimmed steering wheel is the least appropriate performance item imaginable.

Conclusions

The blacksmith or the computer boffin? The blacksmith, of course. The Calais Turbo poses a real threat to the SS Group 3 only in the engine department, and there it distinguishes itself by matching the performance of a V8 of much larger capacity, and easily beating it if you consider fuel consumption: the boffin got his sums right here. Easily the best thing about the car, the engine is an absolute powerhouse with a breadth of refinement that marks it as one of the finest turbo engines we have driven.

In the Calais Turbo it offers towering performance for the money but also towering performance for the handling, even with the supposedly sporting FE2 suspension pack. Be thankful the brakes are so good.

The SS Group A takes honours here not because of its V8 engine. In two ways – fuel consumption and top-end power – it wins despite its V8 engine. It wins because it is a far more complete package than the Turbo, doing a whole range of things, from going around comers to holding the driver in place, a whole lot better. This isn’t the greatest Commodore special ever built, but, even without Brock’s name on it, it is still good enough.