IT’S a year that changed the landscape of Australia.

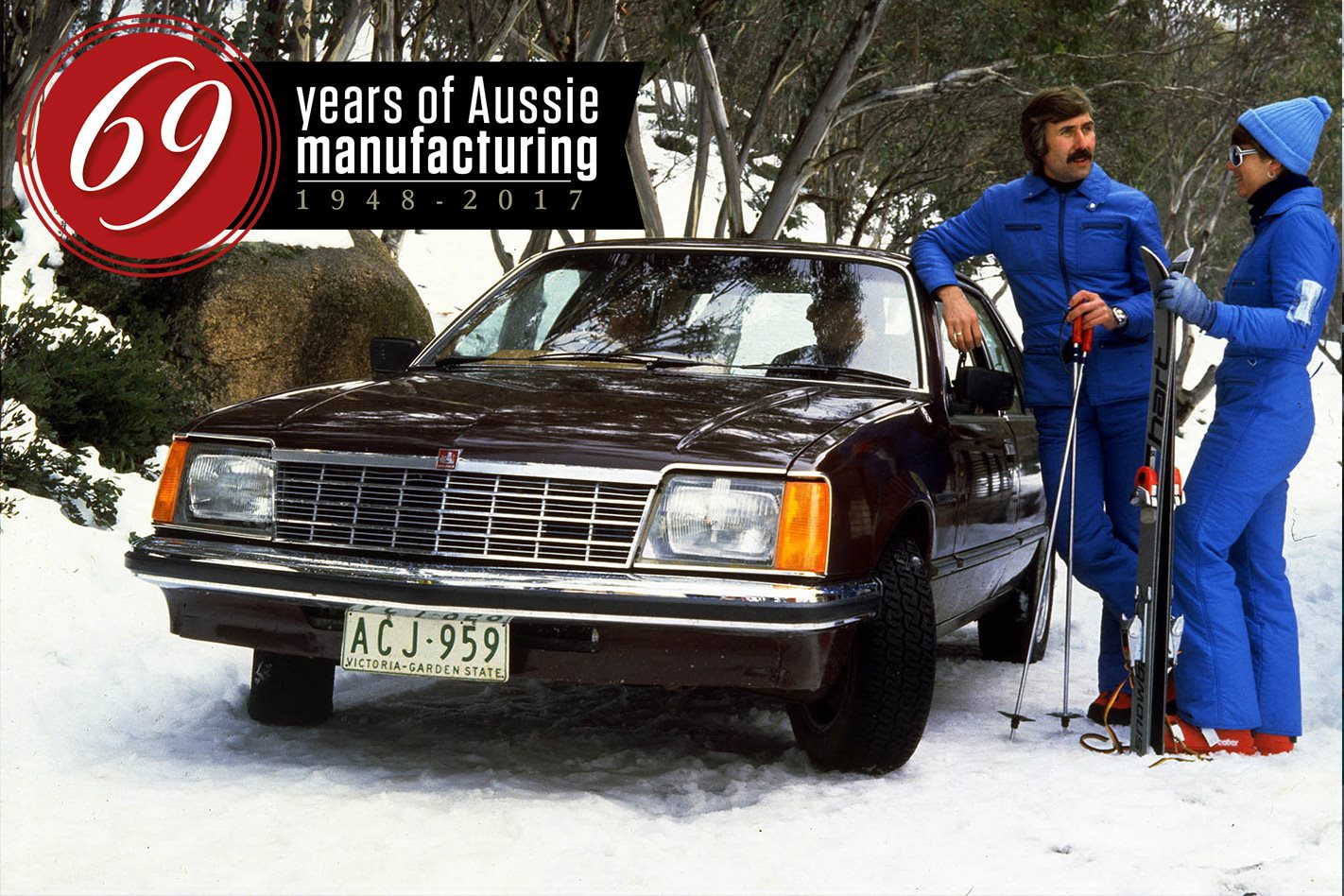

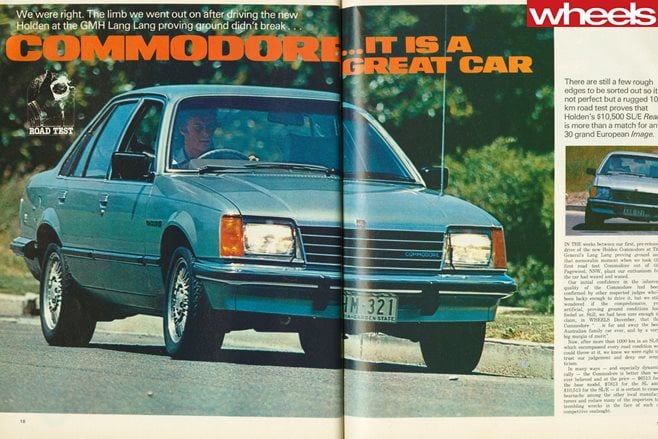

In November 1978, in the wake of the 1970s oil crisis, Holden was to retire the big, fuel-heavy Kingswood and introduce a stunning new model, the VB Commodore, a vehicle loosely based on the European-market Opel Rekord, but with significant local tweaks.

Over at Tonsley Park, Chrysler had been struggling with a unique set of problems. The French had conducted a series of nuclear tests in the Pacific, and in protest, the flow of French goods into Australia – needed for Chrysler’s Centura – had slowed to a trickle. It would result in the Centura becoming a commercial flop for the carmaker. In contrast, 1977’s Sigma would flourish. Three years later, Mitsubishi would lift its one-sixth stake in Chrysler Australia to 100 percent, marking the exit of Chrysler’s US parent.

Australia’s protectionist stance on the car industry was continuing to bite. The Fraser government had upped tariffs on imported cars in 1978 from 45 to 57.4 percent to protect local manufacturing. It didn’t do much: the locally made share of the new-car market would continue to fall, slipping below 80 percent and forcing companies to either scale back their operations, or shutter the factory doors. Mitsubishi would buy out a debt-ridden Chrysler Australia in 1980, and Holden would close its Pagewood assembly line outside Sydney. Renault’s Heidelberg plant would struggle along with heavy losses before pulling the pin in 1981. The import quota program, introduced by the Whitlam government in 1974 as a temporary measure to help car makers remain viable, was still in force.

In 1981, the last Chrysler to use the Valiant name would roll off the production line.

Toyota would introduce volume production of body panels at its Altona factory, while Holden would form an association with Japanese company Isuzu to bring in a ute called the Rodeo.

The late 1970s and early 1980s were a glory time for Holden’s motorsport division. The Commodore would dominate the circuit, with a young bloke named Peter Brock leading the charge.

But things would take a turn for the worst, with the 1983 Button Plan marking a turning point for the industry. All of a sudden, all the previous governments’ successive protectionist policies were assessed as being counterproductive to the industry. Talk started that tariffs needed to be reduced so that Australia would have to compete with the world’s car makers on a level playing field and generate export dollars, or shut down shop. The plan was to suggest that Australia was too small to support more than three manufacturers producing no more than six models in order to wipe out inefficiencies and a lack of competition.

Next: 1983-87: The beginning of the end?