AUSTRALIA entered 1988 with its metaphorical pockets turned out and empty. Interest rates were soaring and the Aussie dollar was bouncing down below US$0.70 as the economy started to hit the brakes.

Car makers, too, were struggling with their own set of problems. Vehicle import quotas, once used to protect the local industry were falling, as were the tariffs put in place to protect local parts suppliers. A proposal framed a year earlier meant the tariff on new cars was slated to fall 2.5 percent a year from its current 40 per cent to bottom out at 35 per cent by 1992. If you think that tariff was high, you’re right; car making remains the most heavily taxpayer-supported industry, estimated to be around $1.6 billion, or $4000 a car.

The 1988 mid-term review of the Button Plan, shaped to rein in a bloated, inefficient industry, was the framework under which the car makers – Holden, Ford, Mitsubishi and Nissan – would need to evolve under until its expiry in 1992, decided things weren’t moving fast enough for the Government’s liking, and recommended the industry reforms be accelerated. In the same year, Holden and Toyota united to form the United Australian Automotive Industries, with the badge swapping sparked by the union eventually extending to the Corolla/Nova, Camry/Apollo and the Commodore/Lexcen tie-ins.

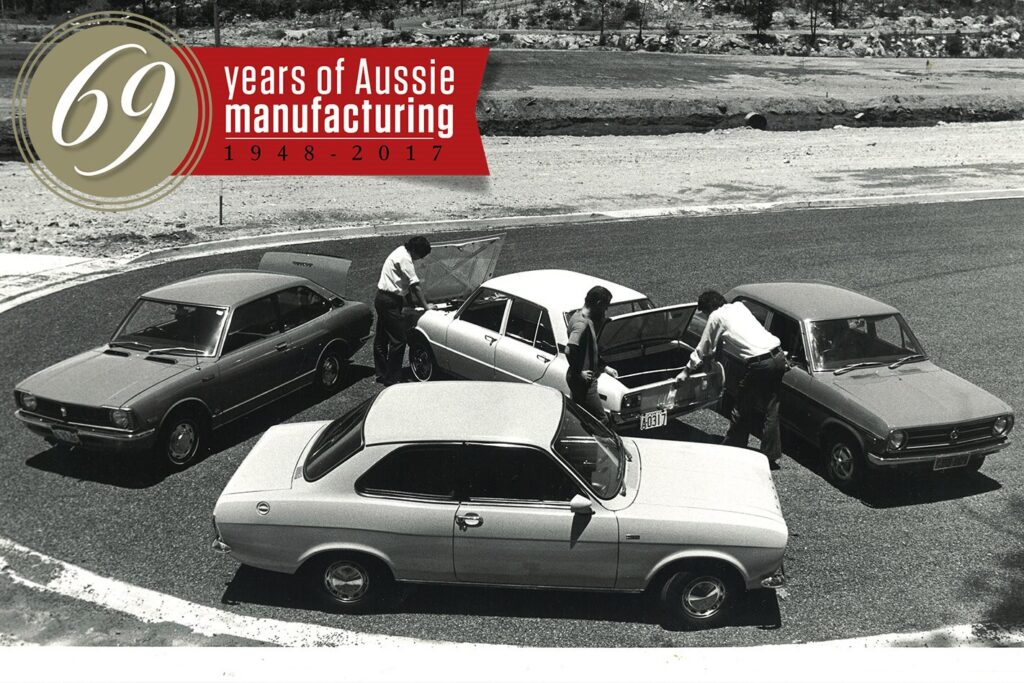

Other Frankenstein-like models included the Nissan Patrol-based Ford Maverick, the Ford Falcon ute-based Nissan ute, and the Nissan Pintara/Ford Corsair.

In the late 1980s, about 400,000 new cars were being registered each year, about 300,000 of them Aussie-made. Exports, meanwhile, numbered around 2000 in 1988, or 0.6 percent of annual production. Despite the strong numbers, Australia had gained the reputation as having one of the world’s oldest car parks – the average age of our vehicles was an ancient 17 years, despite falling new-car prices. Oversupply wasn’t a problem, as Australia’s manufacturing plants were estimated to be operating only at 50 percent capacity, and many were being crippled by strikes and other industrial action stemming from their heavily unionised workforces.

About 2000 dealerships were spread around the country, employing about 60,000 staff; industry estimates pegged the number of people employed in the automotive industry at about 250,000.

In 1989, the Australian automotive industry built 364,000 vehicles worth almost $6 billion. We were still a relative minnow in the export game – only 5000 locally made models sent to other right-hand-drive markets mark the year’s efforts, and we were making more foreign earnings from complete knock-down kits and parts. That would change in 1990 with Ford kick-starting exports of the Ford Capri to the US, with the number of cars steaming out of ports estimated to climb to 35,000 units.

Models produced at the time included the Mitsubishi Colt and Magna, Toyota Corolla/Holden Nova, Nissan Pintara/Nissan Skyline/Ford Corsair, Nissan Pulsar/Holden Astra, Toyota Camry/Holden Apollo, Ford Laser and Capri, the Holden Commodore/Toyota Lexcen, and the Ford Falcon/Fairlane/LTD.

The Industry Commission launched an inquiry in 1990 looking into the government’s assistance programs, and how they could be tweaked to provide the most benefit to new-car buyers. Wide-sweeping tariff cuts were recommended, causing panic in the industry, but the commission’s report released in 1991 did say the industry was starting to wean itself off the taxpayer’s purse.

Inflation, and the talk of even deeper tariff reforms, continued to gallop along in 1991, forcing Holden to take a serious look at its ability to keep producing four-cylinder engines for export. Costs were estimated to rise by about $50 per car a year, severely capping the growth potential of the business against cheaper Asian rivals. And the first rumbles that the government were taking a serious look at the Industry Commission’s recommendations surfaced, with plans to cut tariffs to 15 percent by the year 2000.

Then, by 1992, after 20 years of building cars here and with the Button Plan’s reckoning that the Australian industry could only support a big three industrial car makers ringing in its ears, it had all become too much for Nissan. Struggling with a rising yen soaring even higher against a weak Aussie dollar, and with a string of mounting annual losses, the car maker pulled the pin, its Pintara and Skyline becoming something of Aussie orphans even as its broken race car crushed the field at the rain-soaked and bastard-packed Bathurst.