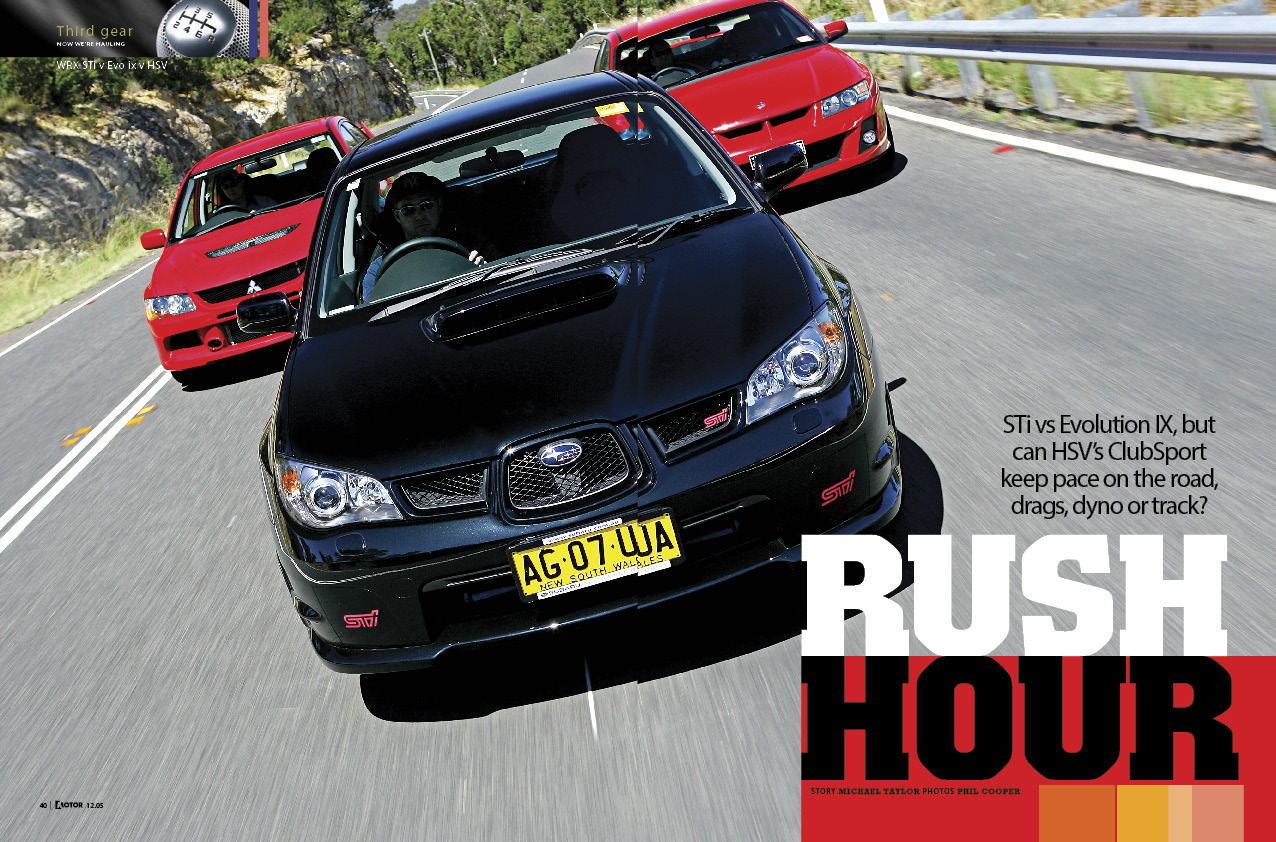

One of these cars is clearly not like the others. It’s the big one with its tailplane safely out of the airflow and a bad case of wing envy. Which is probably fair enough, seeing as it’s never seen a wind tunnel.

What HSV’s ClubSport has instead is space, luxury and rear-drive, straight-line mumbo in a boofy 297kW 6.0-litre V8 package. And it’s the only one allowed to race at Bathurst.

Is that enough, though, to keep the VZ HSV ClubSport on an equal footing with a pair of all-wheel drive turbo cars that are cheaper and seem to get proper, engineering upgrades whenever the weather turns cloudy?

Competition between the WRX STi and the Lancer Evolution is intense; significant advances get annualised model designations by Subaru, and Mitsubishi’s now into its ninth Evolution since 1992 – not including half-steps like the Evolution 6.5.

But the move to the MY06 has been one of the most significant in STi history, with the adoption of the US-spec 2.5-litre boxer four-cylinder giving a huge boost not only to the peak torque, but also to driveability across the rev range. Power goes up 11kW to 206, but power isn’t the STi’s real story.

Subaru’s STi has always had extreme ride and the hollowness of its sub-4000rpm performance as its downside, so you’d recommend them as sole household cars only to extreme enthusiasts. Try as they might, Subaru couldn’t fix the hole by stuffing more tech into a 2.0-litre four so it finally relented, and now the STi’s got nearly 50Nm more torque (392Nm) at 4000rpm. More important to the STi story, it’s noticeable all the way through the range, and it’ll actually give you something more than just the MY05’s intake groan if you open the throttle in fifth gear at 50km/h.

That’s never really been a problem in the Evo, because its torque curve is fatter and the IX’s peak, while lower at 355Nm, arrives at only 3000rpm and the turbo seems to spool up more urgently than the Subaru’s anyway. The reason this model is so significant in the evolution of the Evolution is that it’s finally become a full-line Mitsubishi model in Australia. That means greater integration; it brings in as many cars as it can sell, it gets a six-speed manual and it gets a jump (like the STi – now ain’t that a coincidence?) from 195 to 206kW.

Everybody kind of knows Evos have had more power than that anyway, but Mitsubishi is putting the jump down to the adoption of MIVEC variable cam timing, which switches to the aggro inlet cam at 3600rpm.

The IX is a genuine, fine-tuning evolution, with upgrades to everything from the turbo compressor to the spark plug tips; from the timing belts to the piston oil rings; and from the six-speed gearbox (the Australian VIII had a five-speeder) to the 200 extra spot welds. It also gets tweaks, like an alloy roof, big-arse Brembos and a gun anti-theft tracking system.

Alongside this pair of overachievers, the Clubbie looks a bit of a stick in the mud and it’s the last of the breed before the VE versions arrive towards Christmas next year. It’s got the same baulky six-speed manual it’s always had, though the 6.0-litre V8 gives it an easy, angry power output, and it also lifts its torque prodigiously across the range.

Doesn’t matter what the turbo cars do with their fancy-pants camshafts, because the Clubbie throws out an honest 530Nm at 4400rpm, and it’s got plenty of torque lurking beneath that, too.

This jobbie was, unfortunately, a bit of a hybrid; caught between the last of the Harrop base braking setups and the first of the stupendously good Yokohama Advan tyres that make the car’s handling and accuracy a quantum jump above what it was on Pirellis.

We’ll leave straight line and track performance for another part of this story, but the atmo eight has its advantages. Noise and anger, for one. The LS V8 engines have never been the sweetest spinners nor the most mellifluously-tuned mills, but they do have terrific throttle response.

It’s the easiest of the three to fire off the line (and it’s the only one here with acceleration numbers you’d dare to repeat if you owned the thing) and there’s something about knowing you can spin up the back boots from even rolling first gear starts that gets the testosterone unconsciously cranked up. A couple of quick blips on the throttle, step off the clutch and there they go.

It’s strong, then, and it’s far stronger in rolling in-gear starts than the 5.7-litre LS1 was, even in HSV spec. It’s not as smooth as classic V8s of yore, with the engine ripping and snarling its way through the detonations in its top 2000rpm, but that doesn’t mean it’s not impressive. Take it to the top 2000 revs in any gear and it’s happening quickly, with the shift alarm buzzer annoying you from 6250 and giving you another couple of hundred rpm grace before it hits the cutout.

Then there’s the task of negotiating the notoriously baulky, heavy and mechanical throws on the six-speeder, before you do it all over again.

The Clubbie and the turbo cars use very different philosophies to achieve similar sprint times, though, with the Japanese units force-feeding their way to the traditional benchmarks (though they demand a LOT less mechanical sympathy to do it).

The Subaru’s new 2.5 is superb, with very little by way of tremor or vibration; it spins freely and it manages to retain the off-beat boxer warble on big throttle openings. You wouldn’t be laughed at for calling it sweet.

The torque is wonderful and flat but, for in-gear sprinting, it doesn’t quite have the Evo’s level of boost from mid-to-low rpm and instead relies on its extra capacity to do the job. Still, it feels so much torquier it’s almost like they’ve given it closer gear ratios, and it’s still stupendously strong from 3000rpm.

The Mitsubishi engine, though, feels like it wants to rev harder and it’s just more urgent in real-world driving. The boost is there from low rpm and there’s a frantic surge as it sprints past 3000 all the way to 6500rpm. It doesn’t exactly sound sweet, but it’s not as tremulous as it was and the worst of it is masked by the rush of air through the turbo anyway.

Come off the redline and land either of the Japanese cars into a taller gear – any taller gear – and you’ll be right in the meat of the action with the thing just wanting to erupt again. And again. There’s a brutality to the way the Evo approaches its top 2000 revs, while the Subaru’s a little more refined, but no less effective.

It’s against this that the Clubbie can waste its power outputs. There’s way more grunt on offer, but there’s more weight to motivate as well and the gearing’s a lot taller, with four gears effectively covering the same space the others use six to fill.

But the major area of difference is the way it handles a piece of winding blacktop. Where the all-paws are scalpels, the HSV is a bit squishier, relying heavily on itsAdvans to hang on where the chassis rigidity falls short. It is outstanding on long corners, but less effective on tight or shorter twists. In some of those situations – when it’s stretching itself to just hold on to this pair – it can feel a bit clumsy and oafish.

While the steering is still not as fast as it could be, and it still squats on power down, which unweights the front, everything happens very slowly, very progressively and its bucks, drifts and little slides are the easiest thing to either run with or correct. Which is just as well, because push it hard and you get a lot of it.

The Advans buy you time, giving greater warning of impending grip loss and, importantly, giving constant feedback on the degree of grip loss and what the next step’s going to be.

That’s not to say it’s especially agile (it’s not) or happy about altering its chosen line (which happens more effectively with throttle input, rather than steering). It’s just a less frantic method of eating kilometres and corners, and it’s only a bit less effective for it.

The Subaru, by comparison, makes even average drivers feel like a driving God. Not the God, like Juha. Just a God. Like Petter. It’s perhaps the world’s easiest and best nine-tenths car.

Not that there was much wrong with the MY05, but it’s refinements to the Driver Control Centre Diff (DCCD) and the addition of a torsen front diff that’s done it – and the change in the standard drive balance from 35:65 front-to-rear to 41:59. Understeer? Not now. Stand on the throttle and it pulls you tighter into the apex in contravention of all traditional rules of driving. And common sense.

You can feel the diffs – especially the front one – working to counteract the chassis’ natural tendencies and it all works phenomenally well in low- to medium-speed corners. It’s a bit bizarre, and you get a much harder turn-in bite if you give it some spring back, turn, then stand on the throttle. On the semi-slick Potenzas it makes a huge difference, especially at the back end of long corners.

Get used to that little quirk, though, and it’s as easy as pie to drive at almost its outer limits, and everything about it has been designed to feed you confidence. You can’t get into big oversteer or understeer slides, but you can have little versions of either, depending on your preference.

You still feel like you sit above the roll centre (the STi has 5mm more ground clearance than stock Imprezas), and the whole car feels a lot heavier and more rigid than its weight suggests.

That confidence feed probably starts with the steering and the brakes. The steering weight is just about perfectly matched to the grip levels everywhere – though the rack could be quicker for higher-speed corners, and it can develop a fearful rack rattle when it’s absolutely out of grip on a long corner.

The brakes are superb. They have zero pedal travel before the pads bite the rotors and the pedal stays high and solid and consistent, and the ABS doesn’t interfereuntil it’s all getting very desperate. There’s not a lot of modulation or feel in the pedal, but there’s consistency and, to most drivers, that’ll be enough.

Just about its only quirk is that its grip seems to taper away on faster corners, where the Evo has consistent levels of grip throughout the angle ranges.

The Mitsubishi rides harder with far lighter, far quicker steering. It’s easily the most kart-like of the three. Push it hard and it loves you to stand it on its nose at the front half of a corner, then swing the turbo into action to get the diffs – especially the rear diff – pushing you into line.

And nothing here gets out of the back end of a corner like the Evo does. Even the STi at the peak of its powers, teetering on the edge of its stupendous grip levels, can’t hold the Evo (on the road, at least) as the active centre and rear diffs push drive to different parts of the car to keep the thing on line.

Keep the weight out of your fingers and the steering’s so quick that you think it, and it’s there. The technology is similarly effective, similarly reassuring, but somehow keeps some level of challenge in it for you.

You can throw it into corners at ridiculous velocities and you can almost point it, stand on it and leave the on-board brains trust to sort it out for you. And its new gearshift is a jewel. You think the Subaru shift is good – it is – but alongside Evo’s new six-speeder, it’s a bit slower,mechanical and baulkier. The Evo shift is like its steering. When it’s flowing, the shifts are happening almost without you knowing you’re doing it.

Its tyres don’t have the grip of the STi’s – but it feels like it’s got a slight advantage in steady-state mid-corner chassis grip that (almost) cancels that out. While its brakes don’t have the same high bite point of the STi, they’re just as good, give a little more feedback and progression through the pedal and, like the Subaru, obstinately refuse to fade.

All three of these cars trumpet their credentials through their interiors – the Clubbie’s more luxurious cabin should be a giveaway and, besides, HSV doesn’t have the R&D resources of the others. Still, the HSV seats are supportive and grippy. They’ve also got good adjustment range and the cabin is inherently more quiet than the others, and it’s not as knocked around by coarse chip roar.

The Japanese cars suffer from this, especially from the rear. The HSV rides far better (even on 19s), the Evo far harder, and the STi neatly in the middle.

The STi’s seats look great but they fall away for lumbar support over distance and they’ve not got the Evolution’s grippy bolstering. Still, the Subaru runs a clear second for trim levels, even though the Evo has a more grown-up interior than ever before.

The STi is now a seriously potent device and is the first hyper WRX you’d recommend to someone as an only car. But it feels a bit like the tyres and diffs are making up for a chassis that doesn’t have the Evo’s grip or poise. It’s supremely effective, but in some ways it’s too easy to drive quickly.

Beneath a couple of hundred grand, there’s probably only one other car that can match it. And that’s the Evo. A car that feels a touch more rear-drive (against the STi which feels a touch front-drive) and a car that pleads with you to go harder. A car that loves to be driven on the nose at the front half of a corner and a car that engages the driver more and more as the driver gets more and more committed.

Maybe that’s the compromise they’re walking here. The Clubbie is a more relaxed, better riding, more comfortable way of doing the job, and rear-drive gives it perhaps a wider range of fun tickets.

Both of the Japanese cars leave you in awe of their achievement, especially at the price. The STi is now a capable all-round very fast car with no significant average point, let alone a weak point, yet feels just a little wooden in the way it goes about its business.

The Evo has yet to compromise its core, and it’s just a more energetic, frantic, enthusiastic weapon, and just as forgiving if you get it wrong. There’s always something happening, it’s always asking for more and it’s just a more rewarding car to get the most out of.

It can’t be abuse if it begs you to do it, can it?