Here it is folks, the last Aussie-built Holden Commodore V8.

Yep, the production car that provides the silhouette is sourced from Germany in front-or all-wheel drive and powered by a four-cylinder or V6 engine, but the ZB Commodore that hits Australian racetracks in the Supercars championship is still a locally built, rear-drive V8 … the only hurdle is this one will set you back $645,000.

From the chassis up, this is an Australian car full of local engineering know-how and craftsmanship, just like its predecessors. Yet it breaks new ground because it’s based on an import while sticking resolutely to the local tradition and rulebook.

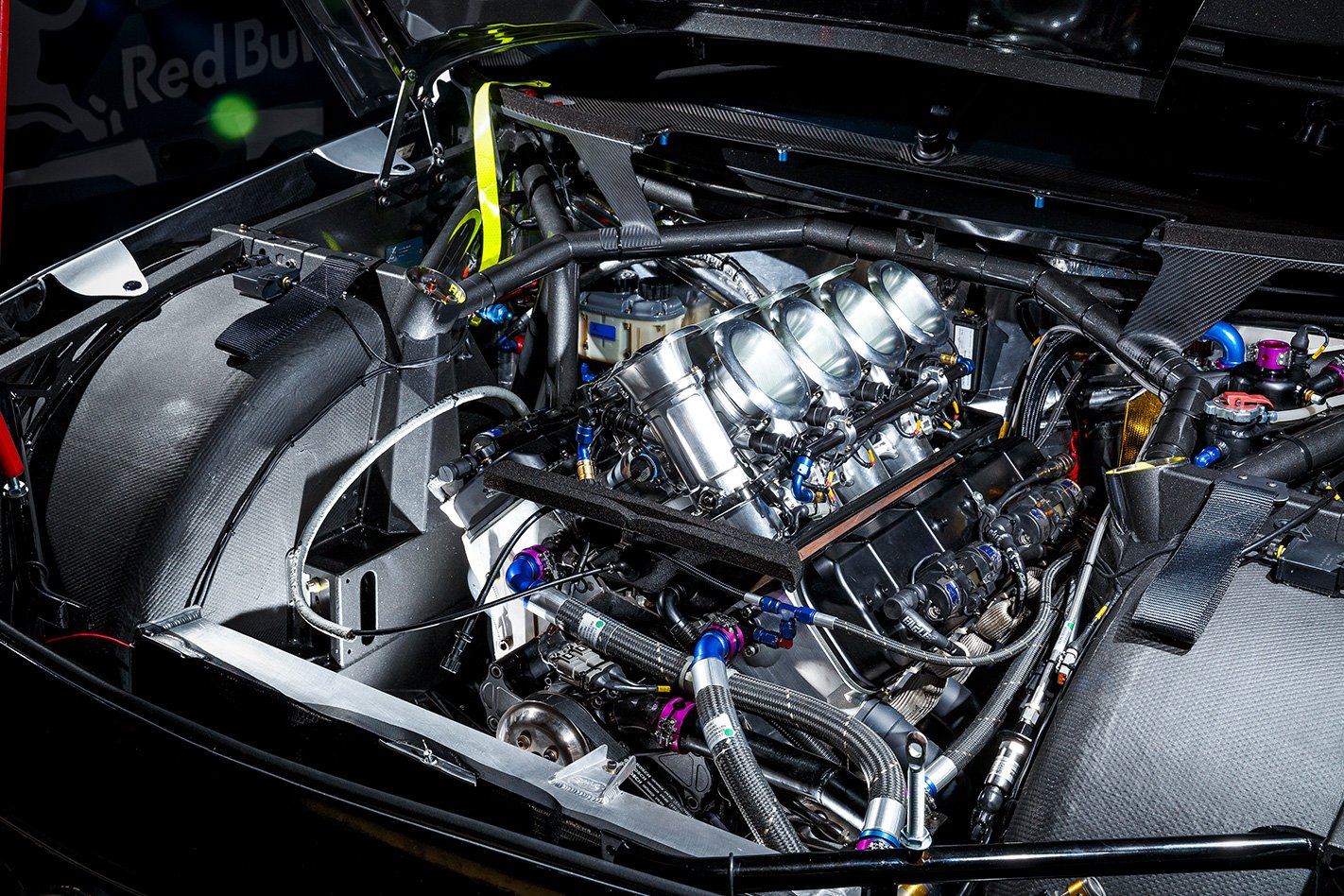

But as of next year, that local identity will be eroded significantly. The Chevrolet V8 engine that’s been developed under the bonnet of Holden touring cars since 1994 will be replaced by a twin-turbocharged V6.

Like the car, the new engine is being developed on Holden’s behalf by Triple Eight Race Engineering (T8) in Brisbane.

Since swapping from Ford in 2010, T8 has been Holden’s most successful team in Supercars racing, so much so that last year it levered the Holden Racing Team name and factory-team status away from Walkinshaw Racing simply on the basis of sheer weight of results.

While it ran three VFII Commodores in the 2017 Supercars championship for Jamie Whincup, Shane van Gisbergen and Craig Lowndes and supported several customer entries, T8 was also developing the new generation Supercar and its engine for Holden.

Not only was T8 competitive on the track, Whincup won his seventh championship, it also had the new car out and running in September and homologated its vital aero package in November. That’s impressive.

Yes, there have been setbacks. The V6 engine was originally intended to debut in 2018, but because of development issues will now only be seen in wildcard outings. Spare parts have also proved a challenge for T8 to manufacture in bulk and on-time.

But all 14 Commodore ZBs entered for the opening round of the championship made it to Adelaide for an auspicious debut, taking five out of six podium spots over two 250km races. Leading the way was T8’s van Gisbergen, with two poles and two race wins in his Red Bull Commodore.

A great way to start the farewell tour. Let’s find out what it takes to build the last great Aussie V8.

Chassis and body

Be they ZB Commodore, Ford Falcon FG X or Nissan Altima, all Supercars are based on the same chromoly control spaceframe. The bodies have to be moulded to fit the 2822mm wheelbase, the defined engine location, suspension points, front undertray position and rollcage. Not the other way around.

The evolutionary nature of Supercars tech regs means much of ZB is carry-over from VF II and simply bolts straight in. Items as disparate as the pedal box, brakes, multi-link independent rear suspension and Albins transaxle are identical across the field. These days, the biggest area of technical design freedom is the double wishbone front suspension. There is tremendous focus on hub design. Triple Eight is up to Mk10.

Long before project manager (and T8 head designer and Whincup’s race engineer) David Cauchi and aerodynamacist Florian Hoefflin and their team physically laid eyes on an Insignia/Commodore, they were working in the digital space using Computer Aided Design (CAD) to reshape and mould body panels to fit the chassis.

In the end, despite the road car’s wheelbase being almost identical with the Supercar at 2829mm, 130mm was sucked from the length of the rear door and the roof.

“You are cutting or shrinking or growing the car so the rollcage is contained in the roof without popping through,” says Cauchi.

Birth of a Hatch

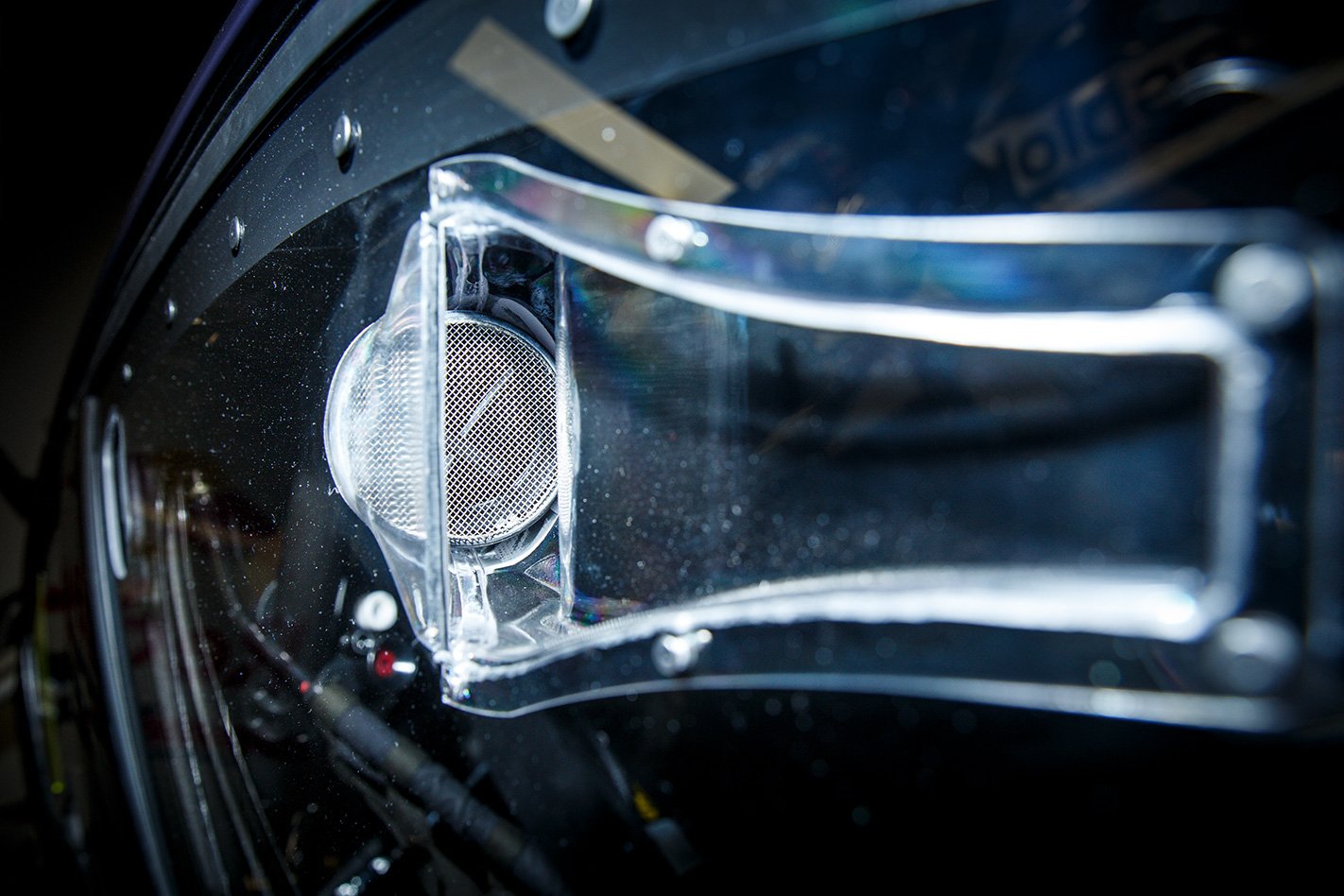

The ZB Commodore is unique in this category because it is a liftback. Every previous Supercar has been a four-door sedan with a separate boot containing the fuel fillers and fuel system.

To create a safety cell for the driver, T8 mounted a polycarbonate windscreen on the control chassis rear firewall. When a ZB driver looks in his rearview mirror he is now peering through two screens.

“Even in a big rear impact where the tailgate gets partially or completely dislodged from the car, the driver’s compartment stays sealed,” explains Cauchi.

“One of our initial concerns was the vision out the back of the car would be reduced, but the drivers actually say it’s better. I think it’s because of how open the boot now is. There is a little bit of sheetmetal we have had to replace or move and that’s probably enhanced the vison a little.”

Body materials

The only exterior panel of the ZB racer that is original material and size is the aluminium bonnet. Every other panel has been modified in some way and is now made from composite material. For added strength, the driver’s door is made from ballistic grade Kevlar.

This is the first time the roof and tailgate assembly of a Supercar have been made from carbonfibre, something that had the Ford and Nissan teams grumbling in Adelaide because of potential advantage of a lower centre of gravity.

T8 went this route because getting production parts from the plant in Germany – especially once ownership of Opel traded from GM to PSA – was impossible. It even bought panels from a Vauxhall dealer in England during the development phase because it couldn’t get them from the Russelsheim factory.

Under the skin it’s much the same story. Door frames, side pressings and some infill parts that connect the panels to the chassis are sourced from Germany, but much more is designed in-house than when Holden teams were supplied ‘spoils’ off the Commodore line at Elizabeth. Says Cauchi: “We’re still a little bit reliant [on the factory for parts], but probably only [to the tune of] 20 to 30 percent, whereas we used to be 50 to 60 percent reliant.”

Aerodynamics

Supercars differs from many big-league motor racing categories because downforce is limited to about 310 kilograms spread across the front and rear axles. This limit – and equalised drag – is enforced by Supercars via an aerodynamic parity test.

For ZB, T8 decided it wanted more downforce on the rear axle than the VFII to cure that car’s tendency to oversteer into corners. The trade-off would be less downforce on the front and more corner-entry understeer, but the team was confident it could cure that mechanically via a revision of the front suspension geometry.

Wind tunnel testing is banned in Supercars, so T8 forged a relationship with Wirth Research, a UK-based aerodynamic consultancy with expertise in Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD).

“With aerodynamics it’s a lot harder to visualise what’s going on than for most other mechanical things, but CFD basically allows engineers to see the things you can’t see,” explains Cauchi.

What they saw when the aero package from VFII was transferred straight to ZB was an even greater downforce load on the front axle – the opposite of what they wanted. “We went through lots of iterations looking for solutions,” recalls Cauchi. “There were no preconceptions and nothing was sacred.”

The side skirt and rear diffuser design were quickly locked away, leaving T8 and Wirth to focus on the front splitter, rear wing position and those oversize endplates. Negating the ZB’s natural forward aero balance was a challenge, something accentuated by the shallow tailgate angle and short rear deck. That’s why there’s such a long plate hanging off the back of the ZB on which to mount the wing.

Up front, aero modifications are only allowed below the bumper line, so within those confines the key change was an aggressive step shaped into the cheek just in front of the wheelarch. That change delivers a little more (compensating) front downforce, but also costs some drag.

It’s the rear that attracts all the attention, though. “The interaction of the deck and the rear wing is quite important,” confirms Cauchi. “That determines how well the wing does or doesn’t work. “Whether it’s right or wrong; well, I’ll tell you in 12 months’ time…”

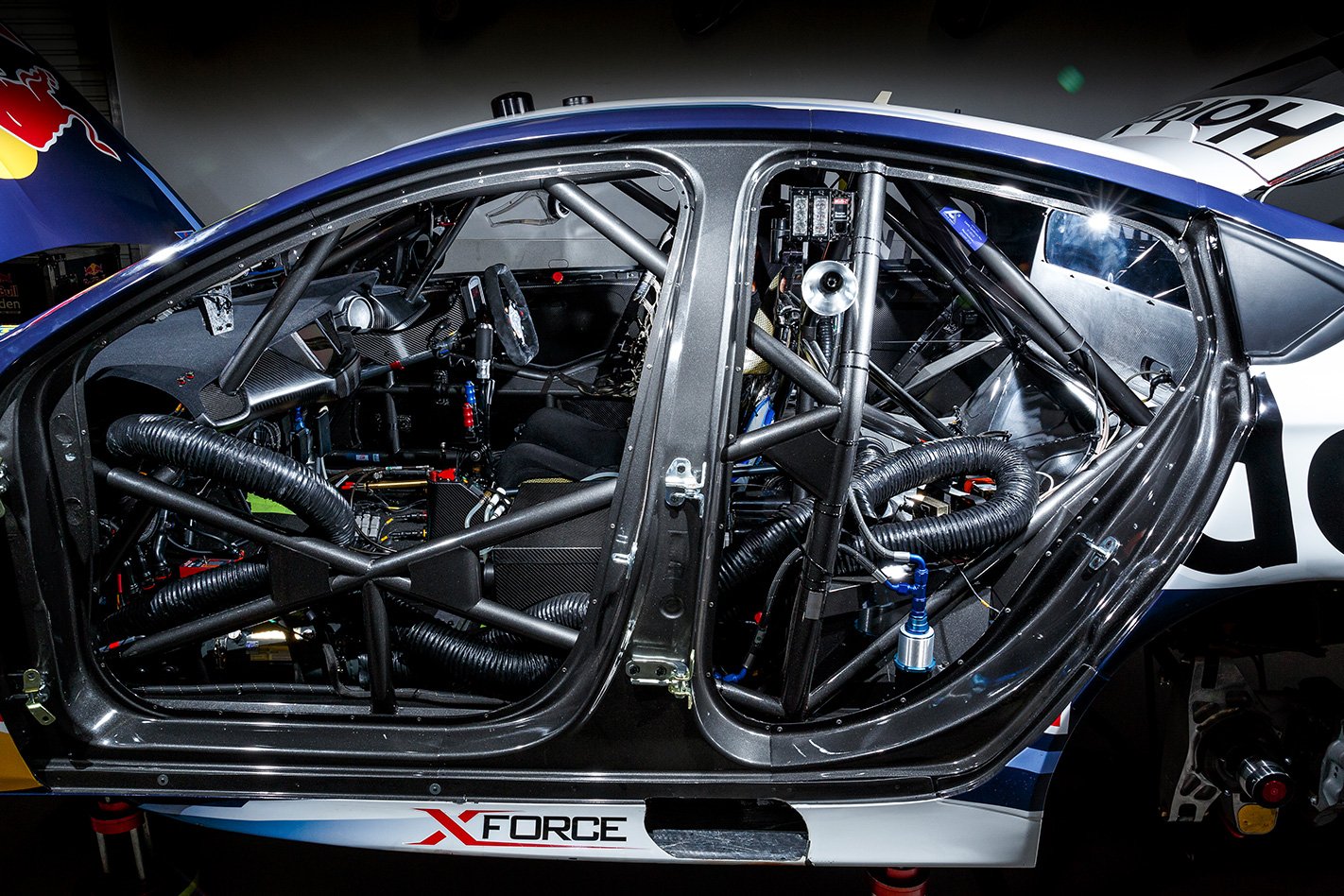

Cockpit

The office of a Supercar is a busy place.

The driver nestles into a Racetech 9129 carbon racing seat and is secured by an OMP six-point harness. Fresh air, drink tubes and comms inputs are all plugged into the helmet. Cool suit piping is attached to the race suit. The Sparco steering wheel skeleton houses a T8-designed electronics module that includes a comms button, headlight flasher, wiper, pitlane limiter, line-locker handbrake, drink activator, alarm acknowledgement, a Motec dash with pages of readouts and shift lights.

The sequential shifter is to the driver’s left along with anti-roll bar adjusters, brake bias adjuster and a carbon-fibre panel including ignition, fire bomb, fuel pump switches and more.

While much of that is carry-over, the top of the ZB road car’s dashboard is replicated in carbon-fibre and includes a rotating screen for advertising logos.

A new generation wiring loom also goes into the ZB, placing it lower in the car and reducing the number of connectors.

“Everything is made very specifically for these cars,” says Cauchi. “This is a controlled and affordable form of racing but there’s still enough intricacies for engineers to sink their teeth into.”

But it’s the new twin turbocharged 3.6-litre V6 that’s the future. Based on the LF4.R twin turbo V6 developed by GM Racing North America for Cadillac’s ATS-V.R GT3 racer, it’s local debut has been delayed because of cooling issues.

In US-spec with a lower power output, the engine retains the road car’s integrated exhaust manifold. That’s great if you want to heat the engine up quickly to combat emissions, but no good for a Supercar that must operate in winter chill and summer heat. So T8 has bitten the bullet and is developing a conventional three-port external exhaust manifold.