In the beginning there was the Audi Ur-Quattro, and it was a car of many firsts.

This feature was originally published in September 2015

It was the first all-wheel drive car in the World Rally Championship, it was the first car to give a woman a WRC win and it was the first to recognise Group B for what it might be.

But nobody much remembers the Ur-Quattro, even if they think they do. The Audi rally car everybody remembers is the Sport Quattro S1. But nobody called it that. It was the ‘short’ Quattro to rallyists and either the Sport or the S1 to the rest of the world.

This was the snarling, spitting, steaming monster of a thing you still see played in WRC highlight reels in bars from Australia to Bulgaria, from England to Canada. This was the Audi rally car with the huge, flared wheel arches and with the enormous rear wing.

And this was the car with the noise. To be fair, even the Ur-Quattro’s noise was pretty special, but by the time it had evolved into its lighter, shorter successor, that noise had become a highlight reel all of its own, a high-revving, limiter-smashing dervish that left such a lasting impression on the good folks at quattro GmbH that they used electronic trickery to replicate it on the TT RS and the RS3.

It’s a deep, rich sound that permeated into and shook up bits most people didn’t know they had. Once you heard a Shorty at full noise, you never forgot it. It was the sound that epitomised the madness of Group B, and no car had a better sound than the Short Quattro. It allowed a few lucky Australians to realise you could have sexiness with fewer than eight cylinders.

To most, it barely mattered the Shorty wasn’t actually much good at being a rally car. It arrived as a production-based machine when everything it fought – from Peugeot’s cracking 205 T16 to the Lancia Delta S4 – had custom-built frames and lightweight everything. Unlike the competition, the Shorty still used the production floorpan (albeit with more than 300mm chopped out), chassis and interior.

But where the faster Group B raiders were far more specialised machines, the Shorty was based on a production car that was heavily based on a road car. Don’t dwell on Audi only building 224 of them, the wonder was that they built so many.

And one of those 224 Shorties is here today, waiting for us to fling it up an Italian Alpine pass and down a Swiss one. This is one of Audi’s museum Shorties (it has four) and, as a note of caution, I’m informed this car cost about $100,000 Aussie pesos when it was new and is worth an awful lot more than that now.

The one waiting for me is in perfect condition, sitting on fat 15-inch Pirellis and guarded with little worry by a museum curator who tosses me the keys and meanders off in search of the best coffee in Merano, a town in northern Italy’s Alpine foothills.

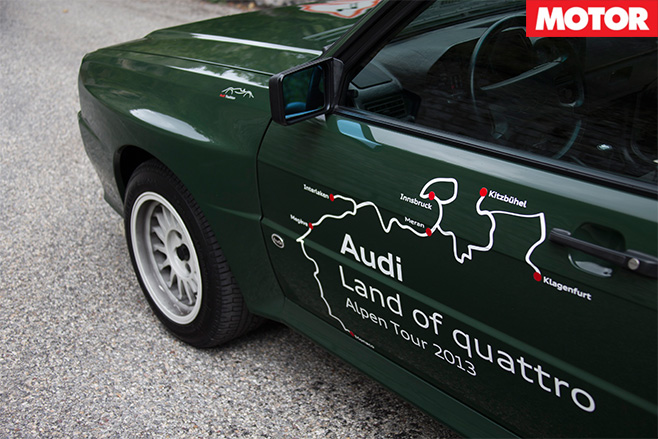

And that’s my combination for the day: a dark green 1984 Sport Quattro, fettled by the same people who built it, its keys and a tank of fuel. It’s such a boyhood dream it’s almost a surprise the key actually slots into the barrel.

The drivers wanted it to be shorter, to minimise the effect of hanging the engine out in front of the front axle line (again, an indicator of how much closer the Audi rally cars were to their production counterparts than the mid-engine 205 or Lancia), so Audi culled 320mm from behind the driver’s seats. There is zero rear legroom in the Shorty and, even then, the bench seat has been chopped in half to fit.

While the boys had the gas axe out, Audi didn’t stop there. It gave the A-pillars a steeper rake to reduce windscreen reflections for the drivers and shoved the front and rear tracks outwards to make it bite harder, then flared the wheel arches to allow fatter 9.0-inch rims under both ends.

But that’s the detail. The core stuff includes a kerb weight of under 1300kg. Audi found the newly-minted Kevlar quite handy, making a bonnet so light you can lift it with one finger.

The 2.1-litre five-cylinder engine was slightly shrunk as it evolved from the Ur-Quattro (rallying had a 3.0-litre maximum and the 2133cc unit just scraped in, thanks to Group B’s 1.4-times multiplication formula for turbo engines) and, as mentioned, unadorned with niceties like an engine cover. It was the first Audi engine to use four valves per cylinder and crossflow heads, plus they machined the block out of aluminium to save 24kg.

But it doesn’t matter what else you look at under the bonnet, because two things grab you. Firstly, there’s an enormous amount of clear air by today’s standards and secondly, the oil-cooled KKK-K26 turbocharger does a good impression of the engine housing of an A380. It’s also an awful long way away from the cylinder head.

And then there’s that key. The five-pot fizzes to life, but you quickly realise there was no marketing pretense in the way the rally engines sounded. They weren’t built to reflect something from the production car because the production car sounds more like a bunch of kitchen appliances operating at different speeds.

There is none of the competition car’s aggression or deep lung capacity. It’s great fat layers of whizzes, whirs, zings and bleats. Every pump, every drop of oil, every cubic millimetre of air and almost every electric impulse can be clearly heard from the driver’s seat and then, on top of that, there’s the relentless, incessant tick-tick-tick of the fuel pump from behind you.

But clear town and a very, very different set of feelings swallows the low-speed impressions whole and one of those feelings is bewilderment. At the first opportunity, I stomp the throttle in third gear trying to pass a tractor and, essentially, nothing happens. This car, the most fearsome Audi for 20 years, accelerates no harder than a Volkswagen Polo. The three-cylinder one (the five-pot is smooth and has no vibrations in it, but there’s also no power). Now I’ve been on the wrong side of the road for what seems like forever and there’s traffic coming the other way.

And then everything happens. WWOOOSSHH! The turbo wakes up and the Shorty is gone, howling like a bear woken by a thousand bee stings and blasting up the Italian alps like the 1300kg tearaway it is. This car hit 100km/h in 4.8 seconds when it was new and it’s even faster today. The trouble is getting it in its power band and out of the reach of the dead hand of turbo lag.

You can barely hear an engine beneath the whistle and howl and the constant wooshing of air, followed by the chirruping of the wastegates trying to bleed off all that boost on the overrun.

But it’s properly fast in a straight line, even by today’s standards. It’s even faster when you take into account its tiny wheels, ancient brakes (though it was the first Audi with ABS) and its dead – and dead slow – steering. We could easily have flung the Shorty up the Stelvio pass, but we’ve chosen a different route into Switzerland called the Ofen Pass, 2149 metres up into the clouds.

There is a mountain of grip in the Shorty and no hint of defiance. It doesn’t take long before you’re sliding the front end, giving it a dab of left-foot braking to bring the back out a few degrees and trying to manage the turbo lag to keep the slide moving. It’s an inexact science that the lag often wins, but the ones you hit are just sweet.

Even with this wheelbase, the car’s handling is ludicrously progressive and it tells you everything you need to know about how to fix anything that’s gone wrong. It rolls around on its soft (by today’s standards) springs and the body movement makes even slow seem fast.

It shoots its way skywards and out of Italy, with a bit of pre-loading (all right, about three seconds’ worth) on the turbo to snatch any tiny overtaking window you might need. The top of the mountain pass is littered with ancient iron furnaces (it’s called Passo del Forno by the Italians) and the roads are smooth and brilliantly taken care of, even if they’re covered in snow half the year.

They say an RS7 should ease my pain, but somehow instant throttle response, greater grip, even more intensive noise and astonishing speed isn’t enough. I want Shorty back.

1984 AUDI SPORT QUATTRO SPECS:

Body: 2-door, 2-seat hatch Drive: all-wheel Engine: 2133cc inline-5, DOHC, 20v, turbo Bore/Stroke: 79.3 X 86.4mm Compression: 8.0:1 Power: 228kW @6700rpm Torque: 350Nm @ 3700rpm Power-to-weight: 176kW/tonne 0-100km/h: 4.8sec (claimed) Top Speed: 250km/h (claimed) Consumption: N/A Emissions: N/A Transmission: 5-speed manual Weight: 1298kg Suspension: multi-links, coil springs, anti roll bar (f/r) L/W/H: 4164/1803/1345mm Wheelbase: 2204mm Tracks: 1516/1492mm (f/r) Steering: hydraulically-assisted rack and pinion Brakes: 4-piston callipers, ventilated/drilled discs (f); 4-piston callipers, ventilated/drilled discs (r); Wheels: 15 x 9.0-inch (f/r) Tyres: 235/45 VR15 (f/r) Price: if you have to ask…

Positives: Performance, handling, provenance, presence, collectability Negatives: Turbo lag, slow steering, average brakes, rarity, price Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars