IN MAY, 1989, a compact, lightweight, affordable sports car hit the road, one the world had not seen before. It was called the Mazda MX-5 and as you read this, it will have been on continuous sale for almost exactly 30 years.

To mark this momentous occasion, we sat down with Bob Hall, the man credited with dreaming up the original MX-5 concept – although he is quick to clarify that conceptualising the car is not the same task as that of turning it into a reality. As Hall himself is a former motoring journalist, at none other than Wheels Magazine, there’s no better person to tell the fascinating story of the MX-5’s conception.

In Hall’s own words:

I joined Mazda North America on October 21, 1981. But it all began a few years earlier, rooted in a conversation I had with Kenichi Yamamoto, then Mazda’s chief engineer. Of course, it was all made easier by the fact I spoke Japanese.

I just assumed I was going to be in Public Relations, because when you’re a journalist and you go to work for a big carmaker, you go into PR. But they put me in design. I doubled the non-managerial staff count of the design department in California – meaning it went from one to two. When they expanded product development they put me in there, which has chased me around my whole career. I really rankle at the ‘father of the Miata’ title I’m too often given, because today there really are no single fathers of any car; it takes a team and a village to develop a vehicle from scratch.

[In the foreword for Thomas L. Bryant’s excellent book, Mazda MX-5 Miata: Twenty Five Years, Hall begins with Toshihiko Hirai.] Remember that name. When something is successful everyone wants to find the creator. I guess that’s just part of the fixation people have with stuff. And now that the Mazda MX-5 has had its [30th] birthday, and [more than] one million have been built, lots of well-meaning individuals are either calling it Tom Matano’s car or are praising me as the father of it. It is not Tom Matano’s car, nor am I the father of the MX-5. The father of the car is the aforementioned gentleman, Toshihiko Hirai. It is his car if ownership must be attributed to a single individual.

Think of a film; there is a director, and there are producers, plus countless designers, writers, cinematographers, editors, sound and lighting techs, and others, not to mention the cast. All too often, history gets rewritten, and the guys who put in the hours and years and really crack their arses hard, giving up anything like a normal life, get left out or forgotten.

I’ll take full credit for coming up with the concept, or at least the idea that the concept of the classic British roadster still had some legs. My dad had this endless run of British open sports cars. I remember us driving together in his Austin-Healey to the Vista Del Mar concours in Los Angeles, and we were driving down Olympic Boulevard in LA and the car just stopped dead in tracks due to a failed SU fuel pump.

Once I got my driver’s licence, I drove my mother’s Volvo, my dad’s later Healey, then Datsun 510s and all kinds of things, and I remember thinking how solid and reliable and neat the Japanese cars were, but why didn’t they have cool, fun sports roadsters like my dad’s Healey?

That stuck with me forever and, a few years later, a day figured prominently regarding my first meeting with Yamamoto and Mazda’s PR chief Bunzo Suzuki. I always felt that there was something left in that idea. I continued to run into Mr Yamamoto once or twice a year, and we’d meet and talk cars, baseball, whatever. We met shortly after the launch of the first Mazda RX-7 and he asked me what Mazda should do next after that car.

So I did this horrible chalkboard scribble, suggesting that Mazda should build an affordable, open, rear-drive sports car. He asked “why?” and I replied “because there aren’t any more left.” Austin-Healey was gone, as was the MGB. The Alfa Spyder was something a little different.

He seemed to understand, but I didn’t think anything would come of it. He excused himself for a moment, and I was about to erase the chalkboard before Suzuki said “let’s take a photo of that” which he did and then I erased it. Something like two years later, I got a call from Kishimoto-san, Mazda’s main PR guy in North America, asking me to come down for a meeting, which turned into the design job offer.

One day I was in the studio working on the B2000 pickup truck and felt a tap on my shoulder. It was Yamamoto, who asked what I was doing. I told him “I’m working on the pickup truck” and he said, “not important right now, you should be working on your lightweight, two-seat sports car”. I’d completely forgotten about it, but he had not. He said he’d talk to my boss, also Mr Yamamoto, but no relation.

They agreed that I should pursue the idea of the lightweight two-seat roadster sports car. However, because the pickup truck is so important to the American market, it must continue.

“You can work on the sports car as much as you like prior to 8:30am in the morning, between 12:00pm and 1:00pm, and after 5:30pm in the evening.” So I began starting my day at 6:00am, having lunch at my desk, and then usually working on the sports car for a little extra time before going home.

I had heard that this is how Yamamoto tested people, to see how much they really believed in their ideas that they would work on them in the beginning on their own time. I guess I passed the test! I spent more time trying to get the idea floated and approved than it took to actually develop the car.

This was about 1982. A lot of people just felt it didn’t make any sense. Mazda had no notion of slipping something so entirely new into the product plan, as Mazda was somewhat reactive to the marketplace at the time.

For example the first kernel of the original RX-7 was originally a redevelopment of the RX-3. Ready for this – if you bought an RX-7 in Japan it had rear seats! The RX-7 made the product mix because it was replacing something that already existed in the market. Bringing something entirely new and previously undeveloped into the product plan was difficult.

They set up a group called the Technical Research Division, and it was designed to look at things that were out there; technologies, studies of human factors, not necessarily to design a specific product, but to study tech solutions, powertrains, and other things that might apply to one or many of the things in the product pipeline. Concurrently the studios in Japan had an idea to come up with a sports car, and we in California had our little sports roadster.

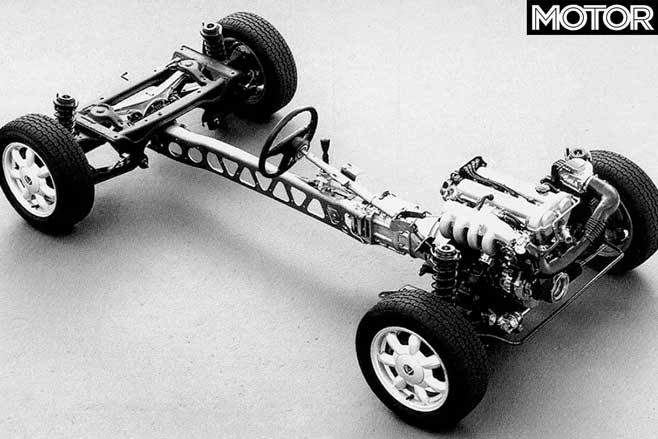

Several ideas got knocked around. A mid-engine car; a front-engine, front-wheel drive car; and our car, which was always front-engine, rear-wheel drive and never deviated from that. Then someone had the idea to have a competition among these ideas, and that’s when our project became a bit more real and legit; we had no certainty that our car would ultimately make it into the model mix. But at least we could formally present it to top management as a possibly official product development program.

Three full-sized clay models were built; we had some challenges with our car because we didn’t have any official engineering support to help with hard points and so forth. Our car ended up being modelled around an RX-7 rear axle. That gave us one dimension – track width – and knowing the various relationships needed for a sports car, we could extrapolate from that and come up with a wheelbase, then other dimensions, so we had some numbers and dimensions to fool with.

Mark Jordan, who was hired in late 1982 and another designer, did this “Gen zero” car, which actually looked a fair amount like what became the first-gen MX-5. Except, since its dimensions were extrapolated around a too-wide rear axle, it was way too big for what we envisioned. The original idea for the car was that it would be done primarily out of the parts bin with hand-me-down items; obviously the less stuff that had to be scratch-designed and developed just for the sports car program, the cheaper it would be to produce the car, and we thought an easier business case to sell.

There was a time during the “competition” between the two Japanese studios and us in California after initial sketch presentations, that we would build clay models. Then there would be a cut down to two and then finally to one, which would get built.

Mark came back from presentations and we were going to build a clay model for management review, but there were some inside political machinations going on and it was possible they weren’t even going to consider our car.

We made our model of clay up to the belt line with a see-through fibreglass removable roof that could be taken off to show what the car looked like topless. What they thought looked only pretty good in sketch form now looked really good in full scale model form.

Ours was the last of the three concepts shown to management. The cut lines where the top met the body were concealed with tape, and after all the presentations were done we removed the tape and pulled the top off, and Sato stood up and said “build that one!”

It is interesting that one of the Japan studio’s concepts was for a mid-engine car, and shortly after the whole management review process was over, everyone attended the Tokyo auto show where Toyota revealed the mid-engine MR2.

Everyone at Mazda couldn’t help but think how lucky it was that we had decided to go with a front-engine, rear-drive sports car instead of a mid-engine design. The overhangs and some proportions of our mid-engine proposal were different, but the overall concept would have been much the same.

As our car was scheduled to come out a few years later (late 1989 vs 1985 for the MR2) it would have looked like we copied them. This was all great for me, as my idea now had front-row visibility with Mazda’s board of management.

Luckily there was a bit of a race to see which of three internal development projects would come in line first. The roadster, an MPV mini-van, or a tiny little 550cc mid-rear engine domestic market city car that was designed, and also a brilliant example of vehicle packaging. This car never made it to market, and thank goodness the MPV got the nod ahead of our sports car, which delayed us a bit.

Ultimately this helped as an airbag was developed for the MPV, which we then had time to package into the MX-5 instead of motormouse belts or some of the other passive restraint concepts circulating at the time. It costs a lot of money, and takes an enormous amount of time to engineer airbags into a car that wasn’t originally designed to have them; so thank goodness our project came a half step behind the MPV, so our car could be engineered from the ground up with airbag systems in mind.

One car that got caught up in this mess was the Australian-built Mercury Capri. It wasn’t an identical competitor to our car, but it would have come out before us if not for the snafu on passive restraints. By the time the Capri was re-engineered for airbags, it came out after us.

The launch of the car was dubbed “Miatamania,” since the production car was revealed in the States at the Chicago Auto show in the spring of 1989, and there were some in the company who wanted to hold the sale date for July 4. Even though ours wasn’t an American car, the first hues you could get were red, white and blue.

Luckily the marketing director, Duane, said “no, put ’em out there as soon as the dealers get them.” So we didn’t have to deal with excuses of scandal by trying to over manage the supply and demand. Demand was far more than many in the company hoped for. Dealers were getting $5K-$6K over sticker for them at the very beginning.

I get a lot of questions about what the car was and wasn’t. Did we leave anything on the table? No, not really, it was the car we all wanted, and it proved right in the market.

Did we ever intend to build it with anything other than an inline-four for power? No. Like the Nissan 1600 and 2000 roadster, the Lotus, the MGB, and so many other of the British roadsters, they all were most right and most successful as a sports car with a four-cylinder engine. Did we plan to race it? Not specifically, we always felt that was best left to the customers and racing teams. We did, however, discuss that you only really get great racecars from great sports cars, but we didn’t set out to build a racecar.

I fought really tough and dirty to make sure that the convertible top was super light and simple. That’s why it’s not buried beneath a hard tonneau cover. I wanted it to be easy to unlatch at a stop light when you wanted to go topless, all you had to do was “throw it over your shoulder” to put it down. It also had to be just as easy to fold up at a stoplight if it began to rain. You didn’t have to get out of the car, you didn’t have to mess with a folding hard cover, and you just grabbed it and pulled it up and latched it down. Simple, easy and light.

What about the ND? I like it. I like the styling, the quality built into it, and the idea of keeping the weight down as much as possible; building in the lightness, in other words.

Working on the MX-5 has, in a way, become an albatross around my neck which, for better and worse, continues to impact my career today. When I joined Geely, we had to stipulate that I would not develop, in any way, a front engine, rear drive roadster sports car for them – no matter how badly they wanted it or wanted me to do it.

I still have some ideas left in my head, and even though the industry has matured, I believe the car business will change more in the next 50 years than it did in its first hundred, so there’s lots of change and innovation, and new products and product types yet to come.

But with MX-5 did we imagine a more than [30] year model run with more than a million built to date? It really wouldn’t have been smart to think that way, but we did believe with some solid updating along the way, and a successful second generation car, we didn’t see any reason it couldn’t live 10 years in the marketplace. Which it has now done so – three times in a row.

30 years and 4 generations of the MX-5

First-generation (NA) – 1989

The one that started it all. Pop-up headlights, lightweight 980kg body and a revvy 1.6-litre atmo four. It really did revolutionise the market.

Second-generation (NB) – 1998

Power upped to 106kW and it ‘races’ to 100km/h in 8.6sec. It’s the only MX-5 to come with a factory turbo variant (and Oz-made SP).

Third-generation (NC) – 2005

Bigger, heavier (1129kg) and with a 118kW 2.0-litre four-cylinder engine. It’s also the first generation to offer a retractable hard top.

Fourth-generation (ND) – 2015

With the introduction of the 1.5-litre option, the fourth-gen MX-5 is the second lightest. Latest 135kW/205Nm 2.0-litre option is the pick for many.