THIS is the transport revolution. It’s going to disrupt things beyond the way we travel. Industries might cease to exist, others will be born. This is where innovation will breed real value and add to our society.”

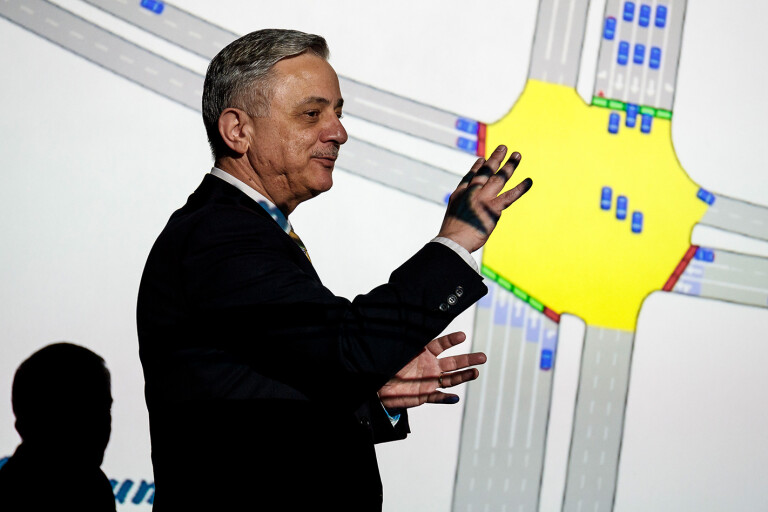

Professor Hussein Dia paints vividly with his words, his gentle deportment energised by a vision of the autonomous future. He speaks from a depth of knowledge gained over 25 years as a civil engineer and academic.

Dia leads the Future Urban Mobility program at Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne and is a member of the Smart Cities Research Institute. His primary interest is intelligent transport systems, or, how technology enhances the way we use our infrastructure, and he is considered one of Australia’s foremost authorities on autonomous vehicles (AVs). In his mind, there’s no alternative.

“The main reason is to cut the number of fatalities. Around the world we lose 1.2 million people to road traffic crashes every year. That’s about 15 aircraft carrying 200 passengers falling out of the sky every single day. We don’t accept this in air travel. It’s shocking that we accept it [on our roads]. The human driver is responsible for 90 percent of these accidents.”

In Dia’s broader picture, electric AVs are the environmental saviours we need. They address issues beyond our immediate concerns like the road toll and air pollution, including the reactive road building that’s choking our cityscapes.

“Over the past 50 years the mentality has been that if you have congestion you build out of it, you add more capacity. That might actually be a nightmare scenario when freeways are already 11 lanes wide. That’s not sustainable. When we do surveys people tell us they want low carbon mobility; they want sustainable transport solutions. They want things that won’t make climate change worse.

“Vehicles are going to be autonomous and they’re going to be on-demand. One of the striking things for a city like Melbourne is we can achieve the same mobility needs during peak hours and over the duration of the day using only 20 percent of the current vehicle fleet.

“You can reduce the number of vehicles on the road substantially if people are willing to share. They need to be shared, otherwise we’re doing exactly what we do now – 1.1 passengers per vehicle, and that’s not going to cut it.

“Some people might not want to share, but the research is showing this is a minority. Younger people are not getting their licences, they identify more with a smartphone than a vehicle and they prefer to be driven while doing other things. Owning a vehicle is an expense that’s parked for 90 percent of the day. If the surveys we’re doing translate to reality, people are no longer interested in owning a vehicle.”

Dia believes his utopian vision is achievable by 2040. By then, the shape of our cities will have begun transforming.

“Fewer vehicles on the roads would reduce the need for parking by 90 percent. Jungles of parking spaces would disappear. To me, that’s exciting because one lane of the existing road can also be removed and made for active transport [cycling/running/walking], or turned into public spaces.”

This idealistic vision is easier to comprehend when looking at the multi-purpose, high-density developments happening in Australia’s largest cities.

“We’re seeing more densification – people in apartments near the city rather than outer suburbs. A good example is Melbourne Central where you have a train station at the base, then retail, offices, and residences. A lot of people living in these areas don’t need a car.

“Melbourne and Sydney are going to reach the 8 million [people] mark in time. Imagine if everybody decided to bring a car with them.”

Dia believes ride sharing AVs will play a major role in relieving pressure on infrastructure, but says investment in the mass public transport systems pioneering autonomous technology, like buses, will be important for easing people into a new way of travelling.

“Melbourne is trialling autonomous minibuses in Carlton and other places. These are perfect initial rollouts of these systems. When you have a fixed route you can easily map it. You can train the artificial neural network program with thousands and millions of examples. The suburban bus even has its own lane so it’s not interacting with other traffic.

“We need to have more pilot studies on the road. We’ve done a lot of theoretical work but now it’s time to take it to the field. How are we going to feel comfortable in the future ordering one of these in the morning and asking our primary school children to hop into it? How are we going to achieve that level of trust?”

One building block is CBD exclusion zones for vehicles without autonomous functionality, ring-fencing areas of high pedestrian activity where autonomous infrastructure is more easily integrated. This is a good intermediate step toward the wider introduction and acceptance of AVs, according to Dia.

Outside of the city centres, and for car enthusiasts, the future of mobility looks a little different.

“Instead of owning a car, or a second car, you subscribe to a mobility service provider. There, you specify your needs and set a budget per month. Families can keep one vehicle and sell the rest. The expectation is that the number of vehicles over the next 40 years will reduce.”

Today, car ownership is cheaper than ride sharing. Dia believes change will come with the reduced expense of EV maintenance and driverless AVs.

“We need to bring the price to the level of owning a car, and without a driver in the front seat that could become a reality. Uber in its latest report said 70 percent of a ride cost is for the driver. Even if you eliminate 50 percent it would bring it down to parity with owning a vehicle.”

Forward thinkers are only beginning to understand the wider practical implications associated with the envisioned transport revolution, and progress is set to come at some cost to the community.

“A lot of people are going to be out of work. In Germany they predict losing 600,000 jobs by 2040. Those are immediate people working in the industry. This is going to have massive impacts, but it’s going to create new types of jobs for people to consider. The cars will travel maybe three times the normal distance per year, up to 100,000kms depending on how many vehicles fleet companies put on the road. You will need to replace them every three to five years for battery wear.”

Supporting infrastructure faces imminent stress given the predicted influx of energy-hungry EVs.

“It is going to be an issue for utilities to balance the supply and demand. One positive is EVs as mobile chargers. If you drive and park one somewhere, it can be plugged in to supply battery electricity to the grid. It’s a complex problem because you need very smart algorithms and infrastructure for metering, but it is possible to instruct the vehicle to charge itself during off-peak hours and monetise your asset during peak hours.

“But we need to look at how we diversify energy sources. What’s the point of having a vehicle plugged to a wire that stretches all the way to a coal mine? That’s useless.”

Data-hungry AVs also threaten to swamp connectivity systems with their huge bandwidth requirements for live mapping and Vehicle-to-Everything communication.

“There’s a lot of hope now on 5G data because that’s mobile. These vehicles of the future generate unbelievably huge amounts of data, gigabytes per second sometimes, and if this needs to be transferred to the cloud, current connectivity isn’t going to be sufficient.

“Governments need to be convinced the demand is coming and invest to expedite the rollout of infrastructure. We need public/private partnerships. It impacts all our lives and it’s too big for one entity to take ownership.”

How the revolution will be supported by government is a question looming large considering revenue from the sale of fuel has a finite timeline.

“At the moment the government gets $11bn each year from the fuel excise. If 80 percent of the vehicle fleet is EVs by 2040, that’s under threat.

“Economists have started to look at what’s called road pricing, or congestion charging. We’ve tried before to suggest it, but no politician wants to come near it. What I like about it is; instead of paying a registration fee, stamp duty and fuel excise, the charge would be user pays per kilometre. There’s going to be more EVs and they will travel more. So even though there’s no fuel tax, the government still makes money.

“It’s government policy that’s going to have the big impact. In China the incentive for the government is to be a world leader in the EV space, and they’re responding to citizen pressure. The pollution is overwhelming. In Europe and India the regulations are due to communities voting.

“In Australia our cities are not as polluted, but we can’t wait until they are. Things are only going to get worse. I’m not a fan of bans, I think that we should leave some choice for people, but it’s those sorts of interventions that might encourage change.”

COMMENTS