For Steve Cropley, back in Australia for the first time in nine years, driving a Holden Commodore from Sydney to Adelaide via Hay and back was ideal for rekindling some old memories and sparking some new frustrations.

First published in the January 1988 issue of Wheels magazine, Australia’s best car mag since 1953.

IT WAS ONLY going to be a little trip, I told them in England. Only Sydney to Adelaide through Hay, then back through Broken Hill. I wouldn’t even be straying outside the south-eastern quadrant of the country into the red stuff and the gibbers.

In short, it’d be the kind of journey which most Australians make casually, for their holidays. Only 3200 kilometres; no more than London to Moscow and part of the way back …

To say European drivers find Australian distances vast is so obvious it’s apt to give even clichés a bad name. In any case, it isn’t that simple. There are huge differences between driving 3200 kilometres in this country and in any other and it isn’t just the width of the open spaces, the weather, or even the cars.

It helps to have been out of Australia for nine years, as I have. You see the contrasts.

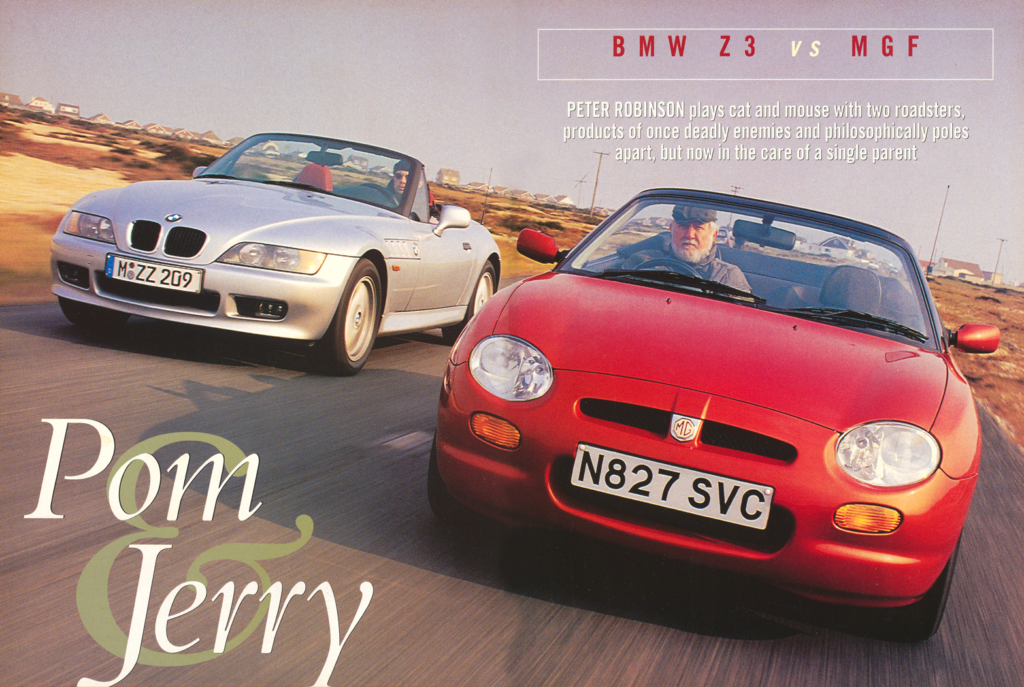

I headed out from Sydney about midday on a Wednesday, an hour or two after the plane landed from London. The plan was to get as far west as possible before a need for sleep took over. Possible objective: Hay. My car was a Holden Commodore SL, a pretty basic sort of a chariot, powered by Nissan’s sweet three-litre six, with a manual five-speed gearbox and an uglier nose than the newly launched Commodore I test drove (and wrote about for this magazine) at the end of ’78. Instantly it had a pleasant, faithful demeanour. Robinson (hasn’t he gone grey?) told me that this car was less well equipped than most Commodores, but the general spec made it a fair example of Australia’s most popular car. Lt came as my first surprise.

Now I remember as well as most people about the six-cylinder heritage of family cars in Australia. I know a bit about the era of the great V8, too, having helped to put the language of poke, grunt and oomph, lumps, mills and donkeys before a few. And having remarked once or twice on the advantages of engines with tyre-shredding torque at 2000rpm.

So when I took off up the Parramatta Road, looking for that new freeway that sweeps you past the inner western suburbs, the worst traffic snarl for a thousand kilometres in any direction, it was the car I was thinking of. This Holden engine is most of a BMW’s. It is smooth, torquey from what I estimate to be 1800 or 2000rpm. It is powerful in the middle and strong as the revs rise, only running out of potential towards the top, where a BMW would still be powerful (and would sound a little better). That this seamless power is delivered by the burning of 91 octane lead-free, a substance they’re only just beginning to hear about in the more backward states of Europe, such as Britain, is the more surprising.

If this Holden is the Australian average, it’s a hell of a long way further up the ladder of luxury and refinement than the best-selling European traffic jammer. In Europe, the four-cylinder engine is king. It goes into almost all affordable cars, even the lower-to-middle end levels of executive sedans like the Ford Granada and Renault 25. Only the most luxurious models get sixes, and there are some pretty unruly ones about (worst among them Ford’s ‘new’ 2.4 and 2.9-litre, bone-shaker V6s). In Europe, it can be hard for the motoring scribbler to remember what smooth is, since he applies the description to too many in-line fours.

They are not, and never will be, smooth. The Nissan injected six, the best-mannered engine in an “average” car anywhere in the world, proves it. Come to think of it, the ordinary Commodore six must stand pretty well in any company: it certainly is wholly quicker, bigger and more luxurious than the Jap car the Japanese buy (the Toyota Corolla). And while it may not be bigger or plusher than the average American tin box, you could gamble pretty heavily that it’s better. Wheels proved it for Holdens when it took a Commodore (albeit a special one) and thrashed competitive Yanks with it on their territory.

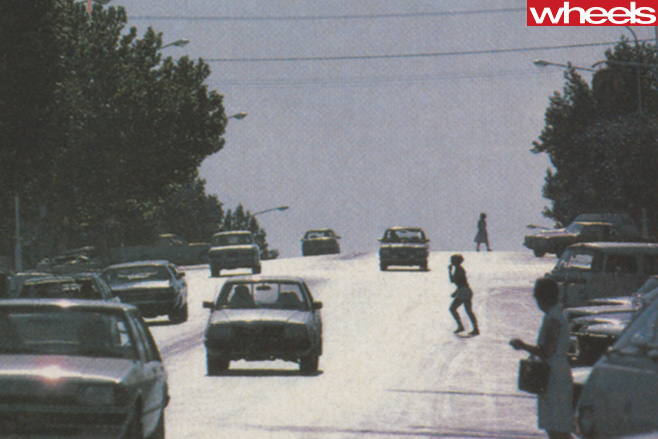

Fifty kilometres out of Sydney, fond thoughts about Australia’s Own (do they still call it that?) had faded from the mind, even though there were examples of the marque wall-to-wall. I was feeling blank horror at the needless obstacles which officialdom has been quietly stacking in the path of Australian road travellers these past nine years. Somewhere near Blacktown, I considered parking the sweet-running Holden next to the kerb and crawling back to the airport on my hands and knees, in the hope of flying to Adelaide instead.

At last, onto the west-flowing F4 we went, the brief stretch on the last of the coastal plain that leads to the Great Divide, another source of slowness. On the F4 our bold masters allow us a heady 110 km/h; I was struck by the way everyone observed it. The cops in patrol cars and bikes are fierce, I heard, and there are forests of signs to tell you that they’re overhead as well. I railed particularly against this pointless harassment. This must be Sydney’s safest road; a 140 km/h limit would make perfect sense. lt didn’t help when I learned a couple of weeks later that the cops are hardly ever in the air, surveying the F4. That seemed even more unjust. Not only were we obeying stupid laws. but they weren’t even up there enforcing them. Just threatening.

The Poms have a 70 mph (112 km/h) speed limit, you’ll be pointing out. lt’s a fact, and it’s as stupid as the one on the F4. But the difference is that it isn’t enforced.

You can pass patrol cars doing 80 mph (130 km/h) on British motorways and you won’t be pulled. They won’t say so officially, but this is because the limit in most EEC countries is 130. On your speedo that really means 140-150.

lt all boils down this way: in Europe, where the population is dense, maintaining traffic flow at as high a safe speed as possible is the traffic planner’s business.

Inhibiting the flow has been shown to cause terrible snarls, accidents and frustrations. In Australia, where traffic is usually lighter and driving conditions almost always ideal, there seems an accent on prevention for its own sake, a lust for lawmaking.

They want us all to believe driving is a privilege, not a right.

But the main privilege is what you and I give to the lawmakers when we elect them. And where roads policy is concerned, they thoroughly abuse it.

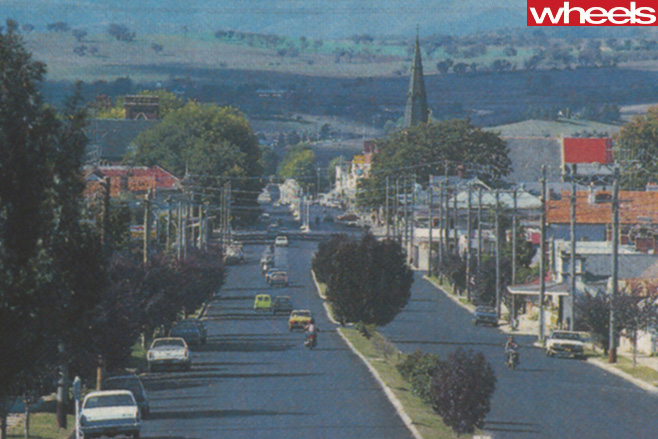

lt was amusing to see that a shocking 20 kilometres of rutted, winding concrete road beyond Lithgow on the Bathurst road, which we all agreed was unacceptable 10 years ago, is still there. They’ve only improved the straight bits, though the worst of the road has been piously peppered with cornering speed signs. I was overjoyed to run out onto the Western Plains within a few miles of Bathurst, fondly remembered as the City of Radar.

lt took the run from Bathurst to Cowra for my brain to return to a state of equilibrium and compute a sensible cruising speed for this car and these roads as 140 to 160km/h. Thereafter, that’s how we travelled.

The country has a magnificence and a kind of, well, dignity at that time of the morning which it loses later when the rest of the world is up and trampling all over its surface. Mind you, all was not right. On the worst parts of this 160km/h road’s surface, the Commodore suspension was kicking up hell.

This 1987 car just does not ride as well as the one they launched at the end of the ’70s. (I wouldn’t make the claim from memory, but other hacks confirm it.)

The official story goes that the first European-theory suspension settings didn’t work in the bush or when you towed a caravan or boat. The latest ones, more firmly sprung, are better at that.

But there’s more to it than that. I drove the Commodore’s near European equivalent, the Vauxhall Senator, just before coming back to Oz. lt’s a car of the same size and power: three-litre injected six, powered rack and pinion steering and an independent rear end, recently rethought. lt is fit to be compared (for refinement) with the new Jaguar XJ6.

Against the Senator, the Commodore chassis felt second rate. Same safe handling, but the steering felt wooden (as if there were unnecessary friction in the system) and the ride, hampered by the age-old links-and-coils rear end, was rough and, in particular, under-damped.

A few years ago I’d have criticised the Holden out of hand. But now, seeing again the special demands of Australia’s roads, I think I understand it better.

Tracks like that across the Hay Plain are evil. They’re smooth at 160km/h one minute; extremely rough the next. You’re always hitting big, wracking bumps hard, so it’s still a fact that cars have to be tough out there. You only need a few 100km/h cattle grids or potholes or spoon drains to punt nice little Italian sporting sedans off into the weeds, or send the semi-trailing arms of your Vauxhall so hard into the body that they measure half a dozen on the Richter scale.

The truth is the cars I know in Europe would not stand up to 150,000 kilometres of high speed cruising in Australia. To build a car that will do it, you need to give it fairly stiff springs (to prevent the constant bottoming) and you need to give it fairly low-rate dampers (so the car can use what suspension travel it has). That gives you a firm, rather under-damped ride by European standards, and it is what this Commodore SL had. GM’s suspension men must be caught in a cleft stick because they can’t simply say this apparently poor compromise is best for the everyman job.

They told me, at Wheels, to leave the main road west of Balranald. Instead, I was to turn south just east of the town and head south, crossing the Murray River, clipping through the top of Victoria at Ouyen and running into South Australia through Pinnaroo. lt was the best advice of the journey.

The signs of a highway melted away as soon as we’d made the left turn. The road was no worse; in fact it was better, having not been battered by the trucks. There were fewer caravans, hoardings, milestones, so we went faster, sometimes showing 180-190km/h without effort. The car’s lack of damping showed up, all right, and so did its less forgivable fault, a distinct lack of aerodynamic development.

This car, alongside a Senator, is unstable in cross winds. Australian distances are vast. This detour occupied near enough to 350 kilometres, most of the distance from London to Paris – and that’s if you count the water.

When you are used to the scale of European maps, you can hardly believe you’ve crawled across so few centimetres of Australia for so many hours hard slog. Yet for keeping up high average speeds, there’s no place like this one.

By lunchtime, 9n the Hay to Adelaide day, I’d done three-quarters of the 900 kilometre journey. The determined car traveller makes progress that simply isn’t available to him on the other side of the world.

Beyond Murray Bridge, I saw my first policeman with a radar gun. He was hiding among the bushes in the middle of a wide median strip, apparently to catch people like me exceeding South Australia’s “liberal” speed limit of 110km/h. I felt sorry for the bloke at first; it didn’t seem fit work for an adult, much less the kind of specially qualified adult we are told police forces now comprise. But this one seemed to be enjoying it. My sympathy changed to something else.

But neither he nor the next bloke I spotted doing exactly the same thing 30 kilometres on seemed to be doing very good business. The Australian driver has long since learned that limits are most rigorously enforced in places where fast driving would matter least; where it is easiest to go fast, rather than most dangerous. It is the sheer cynicism of the system that offends most.

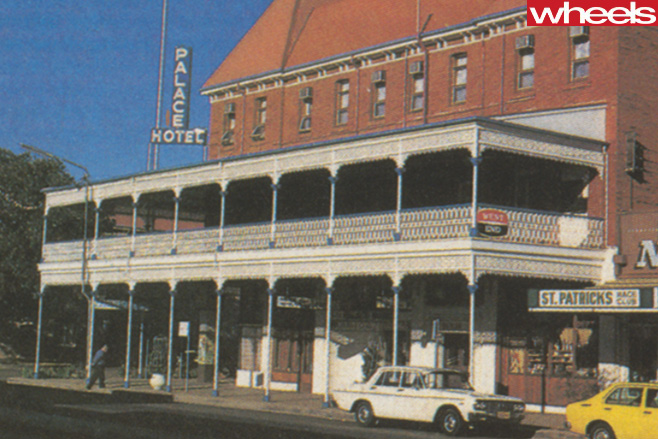

The road to Broken Hill was as I remember it from many trips over the years – fast, well-surfaced, deserted and inviting.

lt is always so good to get up there, beyond Burra, into the country that rolls and folds gently away to the horizon, and to 50 more horizons beyond. Recent rain had turned the verges and slopes into solid green, sometimes purple, and that was unfamiliar. But there are things out there you don’t know you miss until you experience them again: the space, the sky, the silence of all but the wind, the smell of the sun on the air.

The road from Broken Hill to Sydney — as far as Dubbo, anyway- will always be famous to me for the sheer, shimmering distance it allows you to put underneath a fit car’s wheels. A few years ago, Mr Robinson and I averaged 160km/h on it for three hours. That is as quick as I’ve ever been, over such a time.

If your car’s a Holden Commodore, you can sit it on 160km/h, reeling in the road, still able to hear much of the detail from the (ordinary) stereo which they put into SL models.

I set out from the Hill at 4am and was past Nyngan, roughly halfway in the 1160-kilometre Sydney journey, in three hours and 40 minutes. That was despite the animals …

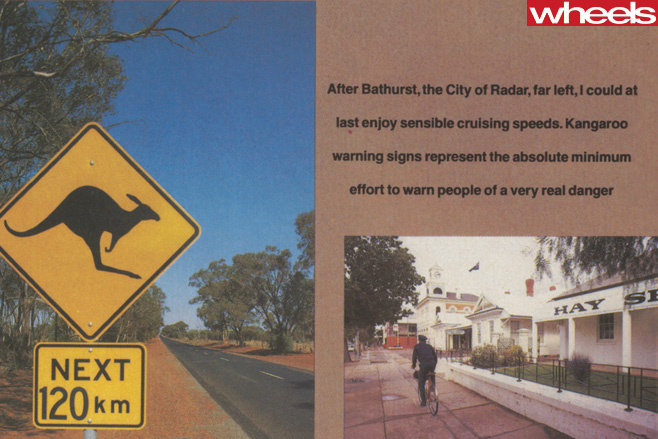

You can make a case for the fact that Australian cars need anti-lock brakes more urgently than anything they make on the other side of the world. If you leave a town like Broken Hill early on a fine morning, when it’s been raining and the grass is thick at the roadside, it’s a good bet that you will need to make half a dozen “phenomenal avoidances” — the brake-and-swerve-at-once kind – every hour until eight or 9 am, to avoid the kangaroos, all of them tall, heavy and well-fed, that line the road. lt doesn’t matter whether you’re doing 80 or 160 km/h.

You’re driving into the sun, they’re dopey with sleep; they will surprise you. And the thought of being joined in the cockpit by 70 kg of wounded, thrashing animal will encourage you to stamp on the brakes rather harder than they teach you at advanced driver’s school.

It is a terrifying problem, yet one visited only minimally by the same authorities who, nearer civilisation, pepper roads they won’t repair with their trivial cornering speed signs. Erecting something outside Wilcannia saying “kangaroos next 100km” represents doing the absolute minimum, I’d say. Some sort of indicator about this month’s degree of risk might help, at least. I will bet you a BandAid to a garage full of ambulances that more people and cars are damaged through collisions with wild animals than ever went off the road near Katoomba for the want of a corner warning sign.

The road from Dubbo to Orange is a peach; after that you’re in civilisation again. Or I thought as much. But I turned through Lithgow town and up onto the Bell’s Line just for old time’s sake. We did intrepid things there 10 years ago.

You can still do them. On the Friday afternoon I was there, not many weeks ago, the road was deserted. The surface was better than I remembered; no obstacles of civilisation had been erected to mar our progress towards Sydney. And the shape of the road was just as I remembered.

It swoops up short hills and through grand, wooded valleys, it hurls you through holes in ragged walls of rock and out the other side onto straights that are always short, and into tunnels made of trees. There are long, long corners, where you get a chance to pause and adjust your car’s stance right at the limit of its grip. And there was the scenery, magnificent on every side.

The Holden, at the end of 3000 kilometres, felt as familiar as any car is likely to get. I didn’t see its tall top gear often in that dash towards Kurrajong Heights but the rest of the ratios, the engine, and even the chassis – good and tenacious on smooth surfaces – made this as good a car as the job needed. It was that for the rest of the journey, come to think of it. We enjoyed it together.