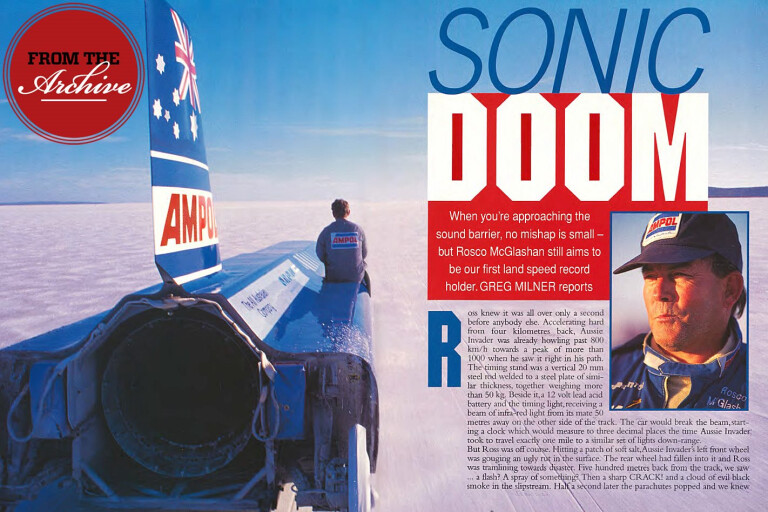

When you're approaching the sound barrier, no mishap is small - but Rosco McGlashan still aims to be our first land speed record holder.

First published in the April 2016 issue of Wheels magazine, Australia’s most experienced and most trusted car magazine since 1953.

Ross knew it was all over only a second before anybody else. Accelerating hard from four kilometres back, Aussie Invader was already howling past 800km/h towards a peak of more than 1000 when he saw it right in his path. The timing stand was a vertical 20 mm steel rod welded to a steel plate of similar thickness, together weighing more than 50 kg. Beside it, a 12 volt lead acid battery and the timing light, receiving a beam of infra-red light from its mate 50 metres away on the other side of the track. The car would break the beam, starting a clock which would measure to three decimal places the time Aussie Invader took to travel exactly one mile to a similar set of lights down-range.

But Ross was off course. Hitting a patch of soft salt, Aussie Invader's left front wheel was gouging an ugly rut in the surface. The rear wheel had fallen into it and Ross was tramlining towards disaster. Five hundred metres back from the track, we saw…a flash? A spray of something? Then a sharp CRACK! and a cloud of evil black smoke in the slipstream. Half a second later the parachutes popped and we knew it was bad. With Ross hitting the brakes so hard they began to melt, the car was still rolling 5 km later when cameraman Mike Goodall and I reached the track. Bits of composite body lay scattered like munched rubbish spilled from a council garbage compactor.

The timing stand was no more. Just the baseplate remained, straddled by the great ruts in the salt. The solid alloy wheels had missed it by 10 cm.

His right eye glued to the viewfinder, Mike found me with his left: "Well, I guess we're going home."

Ross had always said this was his last shot. After three attempts, the sponsors wouldn't stand any more. He kept the anxiety of it muffled under a blanket of edgy humour. So they'd all trooped back across the Nullarbor to the now familiar shores of Lake Gairdner, where a dusty little village sprang up overnight. There was technology and comfort that earlier land speed record breakers could only have dreamed of; satellite phones, huge air conditioners to cool the kitchen and eating areas, a water purification plant, hot showers. Some wag had even managed to haul a spa bath halfway across the country.

Ross had always said this was his last shot. After three attempts, the sponsors wouldn't stand any more. He kept the anxiety of it muffled under a blanket of edgy humour. So they'd all trooped back across the Nullarbor to the now familiar shores of Lake Gairdner, where a dusty little village sprang up overnight. There was technology and comfort that earlier land speed record breakers could only have dreamed of; satellite phones, huge air conditioners to cool the kitchen and eating areas, a water purification plant, hot showers. Some wag had even managed to haul a spa bath halfway across the country.

Despite the technology, land speed record breaking is still a waiting game. On some mornings the tourists would arrive before dawn. They knew this was not a spectator sport, but they came anyway. Big, raw-boned farm boys with calloused hands, or steel workers from Whyalla, they'd drink beer under the sparse shade of their battered hats, and stare out over the blinding salt. Because they'd driven so far Rosco would come down from his camp to stand among them and press the flesh.

Always the jet-fuelled jester, he'd charm them with his self-deprecating wit, answering the same simple questions he'd answered a million times before.

What she run on, Rosco? Kero? Aaaay, Bob, 'ear that? Bloody thing runs on kero! Din' I tellya, ay? And they'd stand in self-conscious little foot-shuffling knots around him, kicking the red dust and glowing with awe that such an ordinary-looking man ... jeez, Jacko, he's just like us! ... was going to strap his backside to a jet engine and go faster than anybody had ever gone.

"Mate, I feel a bit sorry for them," Rosco said. "The poor bastards have come hundreds of miles on the off chance of seeing us do a run. There's buggerall chance today, so it's the least I can do, really."

Like most Australian men, McGlashan uses humour as a form of self-protection, a sword to deflect external assaults and to decapitate the demons from within.

The demons were growing more insistent and there were times when, if you looked deep enough, you knew that the strain of keeping them out of sight and earshot was beginning to tell.

There was no doubting McGlashan's bravery. Always the hot-rodder, there had been many times when things had become a bit sticky. Like that first time back in 1993. The car's front wheels wouldn't grip the salt and it degenerated into great power slides backwards and forwards across the line at 600 to 700 km/h. Rosco would hang on grimly, finally getting out with a line like: "Yair ... mmmm ... she's a bit all over the place, mate."

It was fighter pilot stuff, good old push to the edge and pull her back. And the flip side to bravery was a lack of imagination, for if you thought too much about the terrible things that could happen at such speeds you wouldn't do it.

His crew's admiration had grown like layers of paint, polished by people skills no formal schooling - of which Ross had had very little, anyway - could teach. After 11 years, he and his crew knew each other well. For 11 years he had been making the same jokes, usually at his own expense, and they always laughed.

They thought he had no fear and they were right, up to a point. He certainly had no fear of injury, of hurting himself in a crash - 20 years of drag racing had taken the sting out of that.

But McGlashan knew fear all right - the sickening, paralysing fear of failure.

One afternoon Ross and I drove out to the Bat Cave, the transportable hangar that's Aussie Invader's home away from home. He was to appear in a satellite interview on Channel7's Today Tonight current affairs program. As usual, he joked with the crew as they set up their camera and microwave link equipment. While they were preoccupied with a minor technical hitch, he leaned heavily against the smooth slab side of his blue brute of a car and his powerful shoulders slumped as he squinted at leaden clouds foaming in from the Great Australian Bight.

Only a week earlier, two days after Aussie Invader arrived at the lake for the third time, furnace heat had given way to a quick but vicious thunderstorm. It didn't do any damage, nor did it leave much water on the salt, but sharp memories of earlier visits cut short by bad weather made Ross nervous. The following night he had jumped out of bed at 3 a.m., alarmed by the sound of thunder. Wife Cheryl had dragged him back. It was only the sound of the caravan annex, flapping in the breeze.

Now he was facing it again. For a moment the jester disappeared.

Now he was facing it again. For a moment the jester disappeared.

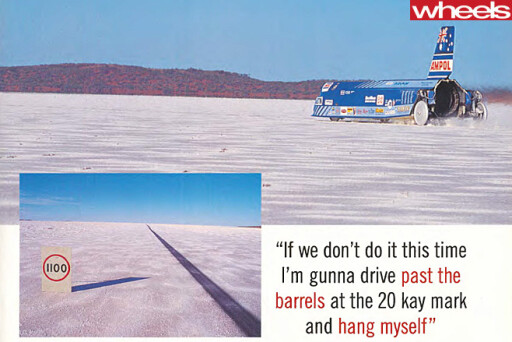

“Jesus, mate," Rosco muttered, more to himself than to me. “Jeee-zuzz! We've gotta do it this time. If we don't do it this time I'm gunna drive past the barrels at the 20 kay mark and hang myself.”

At an instruction from a technician, he turned and looked down the lens of the camera at a TV presenter he couldn't see, adjusted an earpiece, squared his shoulders again and the jester reappeared.

"Yep ... yes, Yvette, I hear you fine, sweetheart. Goddam, yer lookin' bloody gorgeous as usual luv, heh heh heh...”

Late that afternoon, the storm broke in high-pitched squalls across the lake. It tore at the taut skin of McGlashan's face as he and the crew fought to stop the Bat Cave from blowing away. It didn't, but the track was covered by a thin sheet of water.

At dinner, Rosco tried to make the best of it with a wing commander from RAAF Pearce who'd flown a PC9 trainer from Perth to check on his boys. Rosco owed a lot to the air force.

I caught McGlashan's eye.

"How're you going, Ross?"

"Yeah, a bit disappointed, mate."

The wing commander looked away. Ross dropped his voice. His eyes were glazed: "I'm screaming inside." McGlashan was having trouble lifting the sword.

A week after arriving they took the car out for a brief shakedown run, mainly to test some minor modifications and a much bigger tail fin recommended by John Ackroyd, the designer of Richard Noble's 1983 record-breaker Thrust Two. They set him up on D track, the westernmost of four parallel black lines, each a hundred metres apart.

Right from the start Aussie Invader behaved like a bad-tempered child, leaping out to the left. McGlashan wrestled with the controls, fighting the beast back into line, over-correcting and swerving to the right. Instead of ending up 10 km north on D track, he came to rest on C track!

"It's got me buggered," he told Pete Taylor. "It feels like a completely different car." Taylor told me later: "Rosco won't say it, but I think after that first run he was starting to worry for the first time about himself... whether he had what it takes. He was depressed. He couldn't understand why the car had behaved so badly, particularly after things went so well last time."

The wind blew steady and strong from the south for the next two days. The water disappeared. At dawn on February 8, five days after the storm, Rosco went out to raise his own Australian record of 802 km/h. Aussie Invader was set up three kilometres back from the measured mile on a north-bound course.

Thirty metres after the car rolled away from the start, the afterburner kicked in. You couldn't help but be reminded of fighter jets taking off from the deck of an aircraft carrier.

There was something seriously wrong. Aussie Invader veered off to the left again, shaking violently as it hit the ungraded edges of the track. McGlashan was trying to haul five tonnes of rapidly accelerating machine back into line. He completely missed the timing traps, looping wide to the left of the first, arcing back to the other side of the last trap and actually cutting the timing wires clean in half. The chance of raising his own record was out of the question, but they turned him around anyway. He wanted the practice and he wanted to check something else. Was it him, or was it the car?

Again, Aussie Invader veered violently to the left. At 700 km/h the Mirage jet engine inhaled a rubber witch's hat marking a timing trap. Ross had punched the chutes out in an effort to avoid it, but it was too late.

By the time Taylor caught up with him at the southern end, McGlashan had climbed into the intake to inspect the damage. The nosecone of the engine was a mess. Vanes had been torn off, others twisted out of shape.

"The salt's as soft as hell up that northern end," Taylor was saying. Ross interrupted him with an arm around his shoulder as they walked towards the car: "Mate, I've f…ed the engine."

Taylor, an ex-air force engine man, took a brief look and turned back to the boss: "Don't get too uptight yet. It might not be as bad as it looks."

By the next day McGlashan's spirits had returned. The tangle with the witch's hat may have damaged the car, but it had thrown light into the dark shadows of doubts about himself. Aussie Invader was behaving strangely.

Pete Taylor was right. The damage wasn't as bad as everyone had thought. Within a couple of days, they had the engine running again. But the handling problem was bothering them more. True, the salt was softer than the previous year, but the suspension settings had also been changed after Aussie Invader set a new Australian record. The front of the car had been lowered slightly to put more downforce on the back, which had displayed a tendency to skitter, but now the front wheels were digging great gouges.

In team meetings, closed to outsiders, there were strong words. Suspension expert Ian Sutherland stuck to his guns, adamant that his figures were right. The rest of the team, McGlashan included, insisted the car be set up as it was last year. McGlashan got his way.

In team meetings, closed to outsiders, there were strong words. Suspension expert Ian Sutherland stuck to his guns, adamant that his figures were right. The rest of the team, McGlashan included, insisted the car be set up as it was last year. McGlashan got his way.

That didn't work either. Close to sunset on Sunday the 12th, Aussie Invader speared off course and we watched horrified as she lurched to a sudden stop in a spray of salt and sub-surface mud way off to the western edge of the lake. For God's sake! Bogged! Over the radio, McGlashan had bellowed in frustration: "Where the f… is THIS!"

Parked like a beached whale, Aussie Invader had simply settled on her flat floor. They got her out 16 hours later. There was no damage, except to pride. The whole thing was beginning to look like a farce. It was embarrassing.

But Tony Woolfe was smiling. It wasn't the suspension settings at all, nor the weight distribution, nor even the big new tail fin. The command ring, the device which tightens the noose around the jet blast to increase thrust, was out of whack and pushing off-centre.

The superstitious McGlashan would not run on the 13th. It gave Woolfe all day to work - but a thunderstorm was rolling in from the west, turning the Nullarbor to slush. Ross might have only 36 hours. The wind blew all day, hot and strong from the Dead Heart to the north. Ross's demons were in full cry. He sat with his car under the khaki canvas, the Bat Cave flapping and creaking. He thought he was alone. Into the teeth of the wind he let fly a savage, guttural scream of rage and frustration.

The predicted storms sliced off to the south-east. Two days later, the wind finally dropped sufficiently to test Woolfe's adjustments. In a murky post-sunset gloom, Pete Taylor told Ross to keep the afterburner on no longer than 10 seconds. Surprisingly for McGlashan, he followed orders. Over five kilometres, Aussie Invader ran dead straight.

Late on Saturday the 18th, the wind died. Peter Taylor announced they'd run the car up to 1000 km/h. If that looked good, they'd tum her around and make two runs for the world record: an average of at least 1030 km/h over two passes in opposite directions.

In the end, it wasn't the weather that beat them. In the year since he broke Campbell's old mark, the salt surface had changed. At the 13 km mark it was hard to the touch, but under five tonnes of downforce it had been breaking up alarmingly.

At 7pm, McGlashan hit the afterburner hard. One kilometre… 200 km/h… two kilometres… 500km/h and dead straight… three kilometres… 700km/h. Still accelerating, Aussie Invader suddenly lurched sideways! Ross wrestled her, but the left side wheels were jammed in ruts. Bang!

By the time the fire and rescue team got to him, Ross was already out of the car, staring disconsolately down the jet intake. Inhaling the battery and timing light, the engine had shredded. Other pieces of junk had tom layers off the blue body down the left hand side. Some were still embedded in the wreckage.

Swigging on a mineral water, McGlashan's lips snaked back to reveal his teeth in a tear-stopping grimace. "We're done, mate," he said.

Back at the Bat Cave, Rosco's wife Cheryl cried, but he couldn't. He hid his dejection behind sunglasses and a pulled-down cap and, in the late evening air, three cheers carried thinly across the salt.

Record holder Richard Noble plans to start testing his twin-engined supersonic car later this year. The McLaren team is also well advanced on a supersonic project and at least two American teams, including Craig Breedlove, are in the race too. They might appear to be snapping at McGlashan's heels, but it's worth remembering that when Noble set the world record of 1019 km/h in 1983, it took him three years to do it.

If he's done nothing else, McGlashan has suddenly revived world-wide interest in a challenge that in earlier days made the likes of Campbell, Eyston, Cobb and Segrave household names. And if his crew has anything to do with it, McGlashan isn't finished yet.

But he'll still need money. Somebody asked him about his sponsors.

"Well ... I might leave it a while before I knock on any doors." Then a grin. "Maybe a week or two."

A "week or two" it was. Early in March, publicity manager Chris Osborne announced that they had begun building a completely new body for Aussie Invader and that testing of a new jet engine would start in April, ready for a return to Lake Gairdner in November.

COMMENTS