This is the story of a beautiful car, a great road and the classic movie that brought them together.

First published in the January 1997 issue of Wheels magazine, Australia’s most experienced and most trusted car magazine since 1953.

The car? Lamborghini's Miura, celebrating its 30th birthday in 1996, justification enough for this adventure. The road? More difficult, we had to find the road. The Film? The Italian Job, of course, the Caine and Coward comedy in which the real stars were the cars.

Read former Wheels editor Peter Robinson’s story of how he came to write this classic tale.

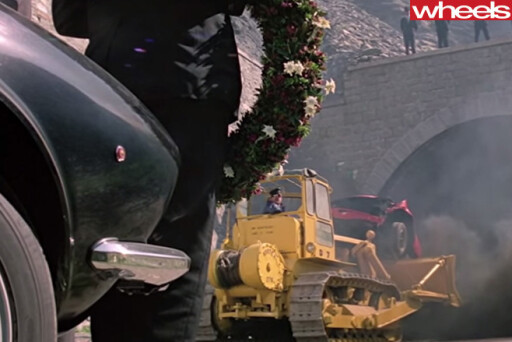

Everybody remembers the opening sequence: the camera pans down from snow covered Alpine peaks to capture an orange car blasting across a bridge, high above a valley. Heart-throb film star Rossano Brazzi wheels the Miura through magnificent mountain scenery as the credits roll. The soundtrack begins with the unmistakable symphony of a Miura engine on song, only for this to fade behind the voice of Matt Monro singing 'On Days Like These'. I'll admit to a preference for the howling V12. Finally, after two minutes 50 seconds, the Miura roars into a tunnel.

There's been nothing in this idyllic opening to suggest what happens next. You hear savage braking, then hear and see a shocking explosion. I remember spontaneously shouting, "No, they couldn't," back in 1969 when I first saw the film. Not even Hollywood, I reasoned, would destroy a Miura. I swear any enthusiasts will react in a similar manner on first viewing.

Yes, the Miura smashes into a bulldozer and hangs, demolished, over the blade. Pulled out of the tunnel and pushed off the road, we see it tumble, helpless, down the cliff face, scattering wheels and bits of body as it falls. It's only on second viewing you notice there is no engine, suggesting another Miura, minus major mechanical components, was substituted.

Yes, the Miura smashes into a bulldozer and hangs, demolished, over the blade. Pulled out of the tunnel and pushed off the road, we see it tumble, helpless, down the cliff face, scattering wheels and bits of body as it falls. It's only on second viewing you notice there is no engine, suggesting another Miura, minus major mechanical components, was substituted.

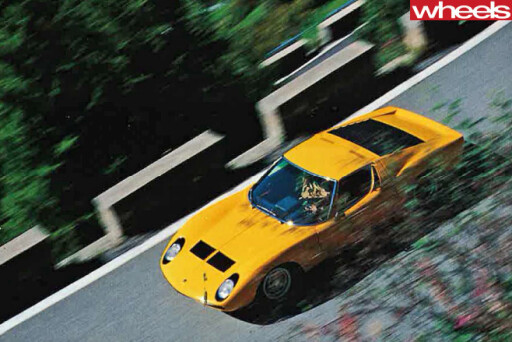

And so it goes, the story of British criminal brains versus the might of the Italian Mafia, the entire narrative exploited to permit a wonderful array of motoring adventures in a wide variety of cars. We wanted to bring car and road together again, reasoning there is no better way to honour the 30-year life of what many believe to be the most beautiful car in the world. Finding a Miura in the vibrant orange of the early cars proved impossible. In the end, we settled for a yellow 1970 S, courtesy of a generous (and anonymous) owner who allowed us to take his car for a day and thereby add a fifth to the 6000km odo reading since a complete rebuild six years ago.

But where is the road? Many viewings of the film suggest it is Italy, but movie makers almost inevitably cheat. Logically, however, it had to be close to Turin, where so much of the film's action takes place. Various sources suggested the road was near Mont Blanc. We rang Remy Julienne, whose team L'Equipe Remy Julienne performed The Italian Job's terrific stunts. One of his team told us the road was "on the old road from Aosta to Mount Blanc".

There is no old road from Aosta to the Mont Blanc tunnel. There's only the existing, banal two-laner that runs up the valley, and is gradually being replaced by autostrada. Even Frederick St George, who organises the annual The Italian Job Run from London to Turin for charity, wasn't sure.

Which is why Fiat design boss Pete Davis and I came to spend a Sunday driving the roads around Aosta in an Alfa Spider. Pete's theory - based on many trips across the mountains into Switzerland and from yet another viewing of the film before we left Turin - was that the road is the Colle Gran San Bernardo.

Which is why Fiat design boss Pete Davis and I came to spend a Sunday driving the roads around Aosta in an Alfa Spider. Pete's theory - based on many trips across the mountains into Switzerland and from yet another viewing of the film before we left Turin - was that the road is the Colle Gran San Bernardo.

From the A5, linking Turin with Aosta and (almost) Mount Blanc, we turned off at Aosta towards Martigny, in Switzerland. Filming of The Italian Job began in 1968, just after the opening of the Gran San Bernardo tunnel. Based on Pete's memory, we took the Colle road that begins on the Turin side of the spectacular new bridge built in the '60s as part of the vast tunnel complex.

Within three hairpins, looking back at the bridge, we knew Pete was right. Today, there's a new hotel complex and more power lines to spoil the view, but this bridge is that bridge. And the road, still recognisable. Yep, it's that bridge on the Colle Gran San Bernardo, immortalised in The Italian Job’s opening sequence and still a spectacular structure recognisable to anyone who knows the film. Success. Except for the tunnel. On this Colle, there is no tunnel that remotely resembles the Miura's black hole.

We ran the Alfa to the 2473m summit of the Colle and the Swiss border, and stopped for coffee. The barman told us that, until they were cleared away by rangers a couple of years ago, bits of many of the wrecked cars could still be found at the bottom of the valley. "We spent days throwing little Mini cars off the top of Mount Blanc," says Michael Caine, slightly inaccurately, in his autobiography.

And the crash tunnel? Somebody must know, but our sources only tell us it's in "another valley". No other clues.

And the crash tunnel? Somebody must know, but our sources only tell us it's in "another valley". No other clues.

Why did the producers use the Miura, and not a (far more famous) Ferrari? That's easy, in theory, though I could find nobody to support my deduction.

Lamborghini's mid-engined supercar shocked the establishment on its debut at the 1966 Geneva show. Eventually, after much persuasion from Pininfarina, who hated to see an upstart rival steal the design lead from Ferrari, Enzo was forced to adopt the mid-engine layout for the Berlinetta Boxer. Ironically, the Boxer, as it is now commonly known, was shown at the 1971 Geneva show, on the very same day Lamborghini unveiled the prototype Countach, the Miura's successor.

Incredibly, the Miura arrived two years before the 365 GTB/ 4 Daytona, the last of Ferrari's great front-engined GT cars, at least until today's 550 Maranello. No wonder Ferrarista hate the Miura.

Lamborghini, the tractor manufacturer, started building cars in 1964. The P400 Miura was the second product of a team of young, open-minded engineers who knew Ferruccio Lamborghini wouldn't go racing. Still, they wanted to build a road car with the engine in the middle, like the sports racing cars of the era. At the Turin show in November, 1965, the Gian Paolo Dallara and Paolo Stanzani chassis was revealed.

Inspired by the Ford GT40 and Ferrari 250LM, Dallara want to keep his car compact. He positioned the Miura's 350bhp, dohc, 4.0 litre V12 transversely behind the driver, with the block modified so it could be cast as one with the gearbox and final drive. Just like a Mini. There was no body and few people took it seriously - not until March and Geneva, when the Miura appeared clothed in a body of extraordinary beauty.

Designed by 'Bertone' and frequently credited to Marcello Gandini, it was actually the work of Giorgetto Giugiaro, who'd left Bertone the previous November. Gandini took Giugiaro's drawing, finalising the production car and details such as the headlight 'eyelashes'.

Designed by 'Bertone' and frequently credited to Marcello Gandini, it was actually the work of Giorgetto Giugiaro, who'd left Bertone the previous November. Gandini took Giugiaro's drawing, finalising the production car and details such as the headlight 'eyelashes'.

"The Miura design is 70 percent mine," Giugiaro said recently, showing me copies of his signed drafting drawings, dated October and November, 1964.

"The idea came from the Testudo [Giugiaro's 1963 concept car based on the Chevrolet Corvair, and the first design for which he was given complete freedom by Bertone J. At the time I didn't even know the engine was transverse.

"When I left Bertone I didn't have the chance of following the building of the car, and the originals of these drawings stayed behind. Gandini took my sketches and finished the car, but the true shape and proportions of the Miura are mine. The sketches are important, but the line drawings give you the detail of the car and are the real proof. There was no time to do proper perspectives. The car could be milled from these drawings.

"One day I should show them, but it would hurt Bertone. What's really important is not who did the design, but that the car was built."

In the end, Ferruccio Lamborghini built 764 Miuras, rather more than the 50 he had at first envisaged. Yet, with the benefit of hindsight, the Miura both deserved and warranted, with thorough development, living on into the late '70s.

In the end, Ferruccio Lamborghini built 764 Miuras, rather more than the 50 he had at first envisaged. Yet, with the benefit of hindsight, the Miura both deserved and warranted, with thorough development, living on into the late '70s.

But Fetruccio Lamborghini and his young engineers were in a huny. They had the world - ie Ferrari - to beat and there was always a new project on the drawing boards, or in the works.

The delicately exquisite Miura was replaced by the spectacular Countach in the early '70s, but there's no doubt which design has best stood the test of time. The Miura, perhaps the sublime automotive beauty and so hauntingly graceful photographer Papior and I spent our day eulogising the styling. By the time we handed it back to its owner, we still couldn't think of a better looking car.

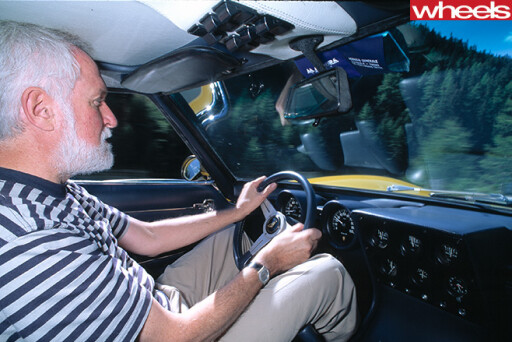

Which is not to say it is perfect. Rossano Brazzi obviously fits the Miura. I don't. The car is incredibly low, so low I feel as if I'm sitting on the road. The view through the panoramic windscreen is incredible; the elegance of the rolling wings, their compound curves merging perfectly into the sunken bonnet, is close to design perfection. My knees are set apart, the pedals so close yet, like Brazzi, I have to stretch to reach the delicate, almost horizontal steering wheel and my head hits the roof.

Tall people find the driving position impossibly uncomfortable. The road feels close, the cockpit distinctive with two huge binnacles for the 320krn/h speedo and 10,000rpm tacho on either side of the steering column.

There is no redline.

"The redline is courage," I remember being told by the Australian Lamborghini importer 25 years ago. He often changed up at 8000rpm indicated, but equally liked to show off the engine's flexibility by accelerating hard from 2000rpm in third. And this when engines still had carburettors, coils and distributors.

"The redline is courage," I remember being told by the Australian Lamborghini importer 25 years ago. He often changed up at 8000rpm indicated, but equally liked to show off the engine's flexibility by accelerating hard from 2000rpm in third. And this when engines still had carburettors, coils and distributors.

Watch the film and you'll notice that Brazzi not only winds on steering lock but also winds it off. More than anything else, it's the absence of self-centring steering that makes the Miura different to drive.

Yet, once above a parking speed, the low-geared, unassisted rack and pinion steering comes alive and it's easy to drive.

There's plenty of grip and far more stability than I had expected, given the early Miura's reputation, but the brakes don't feel trustworthy and the gem·change is stiff in its open gate.

It still feels incredibly powerful, and comparatively quiet below 4000rpm, before the whirr of cams and sucking of the four triple-choke Webers, inches behind your head, are overwhelmed by the bellow of the exhaust. The S is chronologically the middle of three Miura models. The first, P400, supposedly developed 261kW, the S 276kW and the later SV 287kW. However, Bob Wallace, the New Zealand test driver who helped develop all three, says any differences were largely the responsibility of the advertising department.

First is hard to find, the clutch is jerky and either in or out, the pedals are in line with the seat and the steering wheel but articulated from the floor and awkward to use. Moving away from rest is made more difficult because the handbrake can't hold the car on a slope and I've been told the clutch is sensitive and should not be slipped.

Once under way, everything is easier, quicker and less awkward. The steering has a dead spot on-centre, slack that could be 26-year wear, and seems slow to react.

Cruising below 4000rpm is relaxed and tolerably quiet. The ride is far more absorbent than expected, the steering more precise and positive in fast sweepers.

This would have been a very pleasant mode of pan-European transport in the late '60s for it is clear that by the time of the S, Lamborghini had cured the first Miura's stability problems and the tendency of the nose to lift above 200km/h. At low speeds, it doesn't like potholes but the body feels rigid and the grip from the relatively modest 215/70VR15 front and 235/70VR14 rear tyres is better than expected.

The Miura never feels agile - the steering is to blame - but it can be hustled along in safety, sweeping easily through second and third-gear comers. I'm not pushing the engine or the roadholding to the limit, but the impression (if you ignore the poor driving position, brakes and steering - yes, a long list of flaws) is of a civilised, virtually contemporary supercar.

If there is a better photo location in the world, Papior's not found it. The sight of the Miura in the clear mountain air at over 3000m is more than striking. But somehow, for all the near race-car dynamics and packaging, the driving experience remains in second place behind the looks. That's not the way Dallara intended it, of course, but then he didn't know Giugiaro had fashioned so alluring a body for Bertone. For me, it's the beauty of the exterior that dominated the Miura and lead to its starring role in The Italian Job. Nothing else was as exotic.

I loaned my copy of the film to our Miura owner. After one viewing, he saw the director's deception: seconds after Brazzi puts on his sunglasses as the credits finish and unseen by the viewers, the Miura turns around. It's actually heading in the opposite direction down the mountain from whence it came, and is below the snow line and among trees when it hurtles into the tunnel...

Bleedin’ step on it!

Immensely popular in Britain and I Australia, The Italian Job is hardly remembered in America, nor even with good reason in Italy, where it was called La Bombe ltalia.

Fiat and Giovanni Agnelli personally helped organise access to the many locations used in and around Turin. The Italians weren't happy with the result. How, they asked, could Alfa Romeo police cars possibly be beaten by Minis?

One Italian I spoke to recalls angry discussions outside the cinema. The film does raise nationalistic prejudices.

Most people remember the cliffhanger ending, the bus tottering over the brink as the gold slips towards the open rear doors. It wasn't intended that way. Charlie Croker and the gang were supposed to get to Switzerland and deposit the money in a bank - where the bank manager turns out to be the Mafia boss. Midway through the filming, Paramount sensed a sequel and changed the end to make this possible. Sadly, it never happened; agreeing a timetable with the key actors proved impossible.

Er, hang on a minute, lads. I've got a great idea...

COMMENTS