Robbo marks his retirement with a final pilgrimage to the automotive Mecca of Maranello, where he was banned for life. Twice.

VISITING Ferrari is like fighting a war. There are endless long periods of waiting, punctuated by short, sharp bursts of intense activity. Theatrics are not out of the question, either. Today is Waiting Day.

We’re waiting to hear when chairman Luca di Montezemolo can grant us an audience. The phone call comes over one of many coffees; we’re summoned for 11am. While we wait some more in Luca’s outer office, director of communications Stefano Lai asks a favour: The Italian press, another war-like tribe, is suggesting Fernando Alonso wants to move from Ferrari unless the Formula One cars improve. Rather than issue a statement, Lai wants me to ask Montezemolo an Alonso question so that my answer can be used as a proclamation. Why not?

Two men dominate the history of Ferrari: founder Enzo, of course, but also Montezemolo. He doesn’t own the Prancing Horse, but he might as well, so powerful and dominant is his personality on a company recently voted the world’s most powerful brand.

Finally, LDM, the ex-lawyer who, at just 25, was appointed in 1973 to run Ferrari’s F1 team and took Niki Lauda to two championships, greets us at the door, all smiles and charm. “Why don’t you sit in my seat,” he gestures to the far side of a huge desk. “We will do a fun picture.”

“We thank God there are lots of ideas. We are reorganising the Formula One technical area, and there are new methods and innovation in the industrial area. We’ve taken Michael Leiters from Porsche (formerly the head of the Germans’ hybrid program) so that Felisa can step back from the day to day.

“There is huge potential in the cars, even though we have pegged production to 7000 cars a year. We are pushing into new technology and design. With Sergio (Pininfarina) no longer at Pininfarina, this is no small thing for Ferrari.” La Ferrari is the first Ferrari not styled by Pininfarina in 40 years.

The Alonso story, with our photograph, is on the Ferrari website within minutes. I suspect it was written before LDM even gave me the answer.

Montezemolo has no plans for retirement, but he knows I am leaving the business and this will likely be our last meeting. He reaches down, pulls out a carbonfibre base on which is mounted a front wing from Alonso’s 2013 F1 car, and hands it to me. It’s inscribed and signed by Luca. I’m overwhelmed, and for a couple of seconds I can’t speak. My eyes water.

In September 1982, when I first visited Ferrari, Il Commendatore Enzo Ferrari was still very much the autocrat, at least of the racing department. Production of the largely Fiat-managed road car business totaled a mere 2209 cars. My cheeky requests, as editor of Wheels, were various, the theory being that if I asked a lot, they’d grant at least a few. I wanted to go out with a test driver; drive at least one of the new cars, ideally the recently revised V8; inspect the assembly plant; and, of course, meet the then 84-year-old Enzo.

Factory tour out of the way, I then sat down with Luca Matteoni, a marketing operative with responsibility for Australia. Feeling each other out, my Australian naivety no match for the suave Italian, I slowly became aware of a building irritation on the other side of the desk. A grumbling storm.

As a result, there was to be no test drive, no ride or drive in a prototype, and certainly no meeting with Enzo. As far as Matteoni was concerned, I was banned for life. But “life” is a relative term in Italy. Indeed, I later managed a second life ban and was thrown out of the factory in 2001 after writing something else Ferrari found offensive.

With such lows come dizzying highs, though. Dealing with Ferrari was constantly exciting, a motoring journalist’s dream. Across the 16 years from 1988, when I lived in Italy, my visits to Maranello increased in frequency as my contacts developed and friendships were built. I also came to realise that being a “friend”, to most Italians, means never being critical. Few understand the concept of objective assessment from a friend. They take it personally, and immediately you are perceived as the enemy.

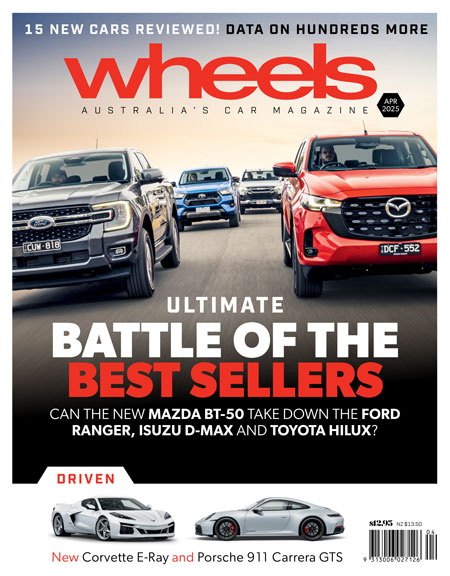

It’s wonderful to be back here again, but this visit very nearly didn’t happen. The email from Stefano Lai in March this year had come at exactly the wrong moment. Days earlier, I’d told Editor Butler that after 52 years writing about cars (44 of them for Wheels) I planned to retire at the end of April. Now this from Maranello: “I am about to plan for April/May a test drive for La Ferrari for a small bunch of journalists… What is your feeling about it?”

How, in all good conscience, could I say no? I owned up to Lai about my retirement, suggested this story and asked for his help in organising to meet old friends. I told Butler I could make just one more trip.

My visit started deep inside Ferrari’s F1 shop, a location too secret for photographer Tom Salt’s cameras, for the first of three technical briefings on La Ferrari.

Franco Cimatti greeted me. “When do I start?” he asked. He’d read my June Wheels column, nominating him (with Gordon Murray) as the engineer to co-ordinate the building of my ideal car.

I first met the Italian-born, American-educated engineer at the launch of the 456GT in 1992 and interviewed him the following year. Today his title reads Head of Vehicle Concept and Pre-Development Department, and his fertile mind is one of the key reasons why today’s Ferraris are so good.

Cimatti planned the radical architecture around the seating position. By changing the driver’s posture, they lowered the H-point (hip location) by 30mm. Removing the seat means the driver sits on an Alcantara-cloaked pad set on the tub, without seat springs. For access, Ferrari cut away the sills and integrated them into the doors, hinging the now large, deep wings off the top of the windscreen pillar and roof. It’s a brillant solution.

“We didn’t focus on interior space in terms of volume, but how much room the driver really needs,” Cimatti says. “Space saved was space that could be used elsewhere. We think of it as a shrink-wrapped driving position.”

I’m bombarded with impressive numbers for La Ferrari and my jet-lagged brain struggles to absorb them. But I’m stirred by Ferrari’s GT dynamics simulator, set for a lap of Ferrari’s fantastic 5.2km Mugello circuit in the Apennine hills north of Florence. Matteo Lanzavecchia, who’s in charge of vehicle performance, says the simulator achieves 99 percent accuracy in terms of lap times and is so sophisticated that it includes accurate anti-dive and squat, and corner-specific load transfers. Surely, in La Ferrari, the ultimate gaming set-up.

It’s a sunny day and Fiorano is welcoming: the old farm buildings beautifully restored, an F104 Lockheed Starfighter still on show behind Schumacher’s championship-winning F2001 F1 car. I rode with the champion on three occasions. Only months after he became a Ferrari driver in 1996, the launch of the 550 Maranello was to include having the motoring writers driven around the Nurburgring GP circuit by one of five Ferrari drivers. My friends in the press department ensured I was paired with Schumacher.

“Now we will go fast,” he told me at the beginning of our second lap. Watching every movement, I quickly understood that hands, arms, feet and eyes were working as one – throttle, steering and brakes in total harmony as if they were a single control. Michael was a picture of calm amid the fury as he talked me through his subtle actions. The 550, suspended in time, drifted through one 240-degree bend in a single masterful sweep.

More waiting. The call came at 5.30pm. Schumi was polite enough to say he remembered me from the earlier drive and chatted openly about his minimal involvement in the Enzo’s development, despite the PR spin. “I don’t rate myself being involved in road-car development,” he told me. “I’m not so interested, it takes so much time.” And there was genuine concern he would lose his licence if he did too much of his unique brand of road testing, which involved drifting past a police car on at least one occasion.

The third meeting with Schumi was when Fiat named a special edition of its baby Seicento after him. I persuaded Fiat to send a car by truck from Turin to Mugello, where Michael was testing the new F1 car, and was slotted into his schedule for one memorable lap.

Two identical La Ferraris await: one for the road drive, the other, inside Fiorano’s now enclosed telemetry garage, for circuit lapping. But not before three shakedown laps sitting alongside lead development driver Raffaele De Simone. We burst on to the track, Raffa’s skilled hands and feet feeding in the power, smoking both rear wheels through a 160km/h, third-gear sweeper while constantly adjusting the car’s attitude.

My La Ferrari driving impressions appeared last month: for now, you only need know the LF is a time machine – you are here and then you are there, with nothing but shrill sound in between. You are never out of the power band and the speed is relentless, brutal and instantaneous. Throttle reflexes are hair-trigger fast. I’m happy to admit that at the limit, the sheer, violent speed is way beyond my talent. Then it’s over, and I’m grateful to hand it back without embarrassing myself.

Time for a tour of the LF assembly line. No right-hand drive, though that hasn’t stopped “somewhere shy of 10” Australians forking out $2m-plus for the pleasure. Each car takes 170 hours to hand assemble, about the same as the F50 and Ferrari Enzo (a Golf takes about 18 hours).

Discussion turns to La Ferrari’s superb styling. Ferrari claims its appearance is driven by aerodynamics, that every line, every opening, is about air flow and cooling and downforce. All except one, I insist, referring to the little crease line that flows from just in front of the rear wheel opening, up and over the flank to the base of the tapered glasshouse. Cimatti smiles. “You’re right, at the Geneva show last year (Giorgetto) Giugiaro called me on the same thing.”

Road time in La Ferrari takes photographer Salt and me on a set route through the tight, undulating hills south of Maranello. Magically, the car starts to shrink; the steering is linear and unfailingly direct; the ride, having decoupled the dampers to “bumpy road” while in Race mode, is astonishing; the carbon brakes instant yet easy to modulate; the performance beyond words.

My first Ferrari, a Dino 246 GT, set the pattern way back in 1970 and, with a couple of notable exceptions, mostly the Mondial and 348, the cars from Maranello have brought me great joy.

The memories, stored on my brain’s hard-drive and never to be deleted, are now priceless.

Great advances

FRANCO Cimatti (above) works in the future. Two decades ago it was 15 years out. Today, given the rate of progress and competitive pressures, it’s closer to 10. But today I ask Cimatti, now 55, still thin and with close-cropped hair and wire-rimmed glasses, to nominate the three biggest advances over the last 20 years.

“Electronics supersedes everything, but it’s too obvious,” he admits before nominating anti-lock brakes. “ABS is still the biggest safety improvement in cars. Take out any driver aids you now have, but leave me ABS. Think how they minimised stopping distances.”

Second: “The advances in tyres. Road-tyre grip has gone from 0.9g to 1.3 to 1.4g, wet and dry, and it’s coupled with lower rolling resistance, more comfort, lower rolling noise and lower temperatures from the black magic of tyre compounds and tread design. I liken tyres to the needle on a turntable. A poor needle creates lousy music.”

Third: “The dual-clutch transmission changed the interaction between car and driver in enabling the driver to keep both hands on the wheel to exploit all the performance. Everybody has had issues, but remember it’s still first-generation hardware.”

What’s next? “The biggest challenge is about compatibility with CO2 emissions (but) we want the Nurburgring lap record, not to be the most efficient car with the lowest CO2.”

Ferrari’s supercars

WHENEVER a new Ferrari supercar arrives, we wonder how they can possibly top it. It happened with the F50, then the Enzo, and now La Ferrari. Surely it’s not possible to surpass La Ferrari? And yet, I don’t doubt that a decade from now a new supercar will do exactly that.

I missed driving the 288 GTO and only experienced the F40 on the road. Still, when the turbos lit up, it needed your constant attention; a raw and so exciting machine that still blows people away.

With the F50, Enzo’s surviving son Piero Lardi Ferrari, who still owns 10 percent of the business, built an F1 car for the road. The F1-derived atmo V12, mounted directly to the carbonfibre chassis, created massive and unsolvable NVH problems. So Ferrari never let journalists drive the car with the removable carbon roof in place. The F50 was much easier and more predictable than the F40. It was possible to get the F50 so far sideways that the steering was against the bump stops on opposite lock.

Seven years later I returned to Fiorano to drive the Enzo. Before being entrusted with the car, lead development driver Dario Benuzzi demonstrated its fantastic performance. The 6.0-litre V12 stretched to the 8200rpm limiter in every gear, we hit 240km/h in fifth through the kink before Fiorano’s 90-degree right-angle bend.

La Ferrari reaches 270km/h at the same point, just 20km/h shy of the best F1 speed. Asked to choose from these supercars, I’d take La Ferrari without hesitation.