The first time Wheels founding editor Athol Yeomans cracked the magic Ton – 100 miles per hour (160km/h) – he was driving a modified FJ Holden.

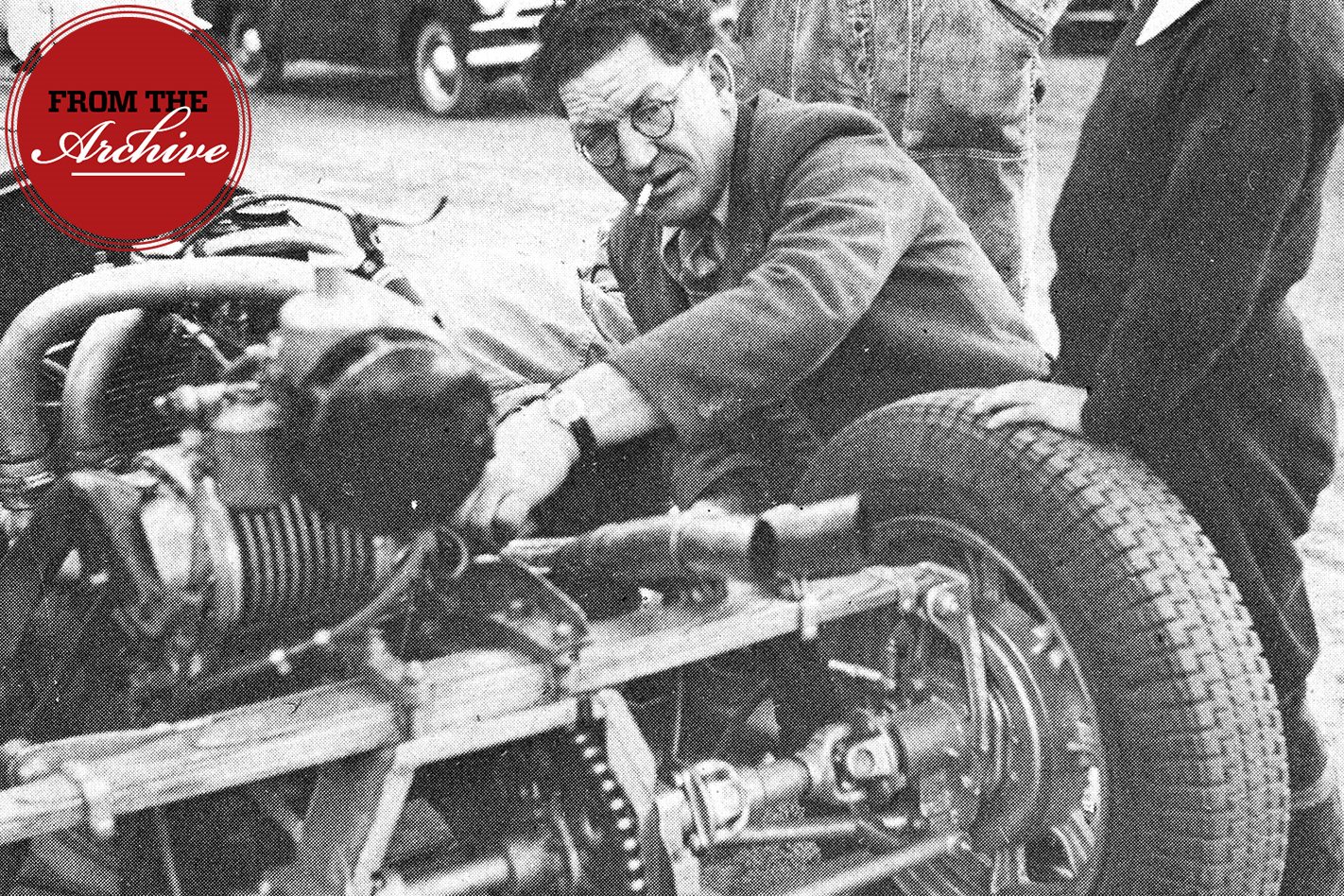

The secret to its wildly increased performance was a cylinder head modified by Phil Irving that upped the power to 90bhp (67kW), a 50 percent increase over the standard ‘grey’ Holden engine.

Read Rab Cook’s classic story, as published in the February 1974 edition of Wheels.

Repco produced about 100 of these completely rebuilt engines and they quickly became compulsory for anyone wanting a truly hot Holden.

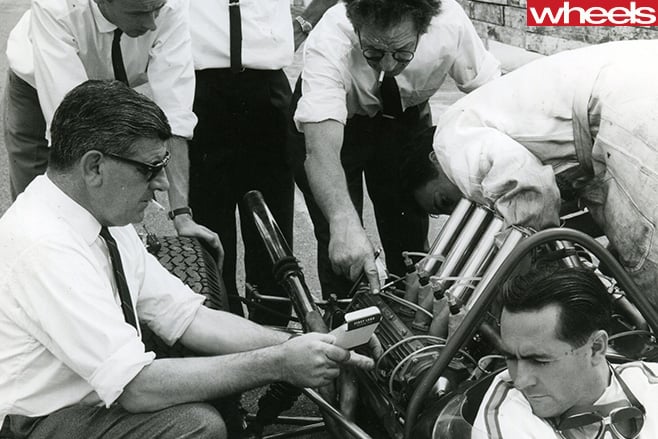

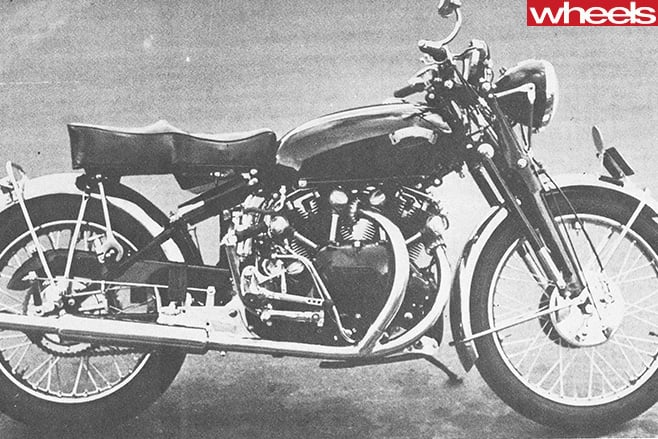

Irving is best remembered in motor racing circles as the designer of the 1966 and 1967 world championship Repco-Brabham V8 engines. He could, as Rab Cook pointed out in his 1974 profile of Irving, just as easily be known as the designer of British Vincent motorcycles, the prolific author of a number of significant automotive books – the best known probably Tuning for Speed and his autobiography – and as the writer of hundreds of articles for car and motorbike magazines.

When Cook moved to Australia in the early 1970s (and began writing freelance for Wheels), Irving provided him with a car for the first few weeks after his arrival. Irving was that sort of bloke.

In his later years, Phil’s Warrandyte (Vic) home, Owl’s Nest, housed an old Land Rover and at least two ‘aunty’ Rovers from the 1950s, plus sheds containing dozens of old motorbikes in various stages of repair.

Irving, a great Australian, deserves wider recognition for his many achievements.

Simplicity the key to success

Phil Irving summed up his engineering philosophy in Australian Motor Sports & Automobiles (June 1967): “In my view, blind worship at the shrine of the super complicated is a thing to be eschewed with vigour – the simpler a thing can be made, provided it gets results, the better.”

In defending his simple Repco-Brabham V8 against engines like BRM’s hugely complicated H16 and the heavy Maserati and Ferrari V12 engines, the ever pragmatic Irving argued that a broad spread of torque was more important than top-end power. Before the new three-litre formula arrived in 1966, the pundits had talked about the need for at least 350bhp. Phil called this “printer’s ink” power and made the point that Brabham still scored three pole positions on his way to winning four of the ’66 season’s nine races, en route to clinching the world championship and manufacturers’ title.

To honour Irving’s “great achievements”, CAMS named its highest engineering award the Phil Irving Award.

Irving died in 1992 at the age of 89.