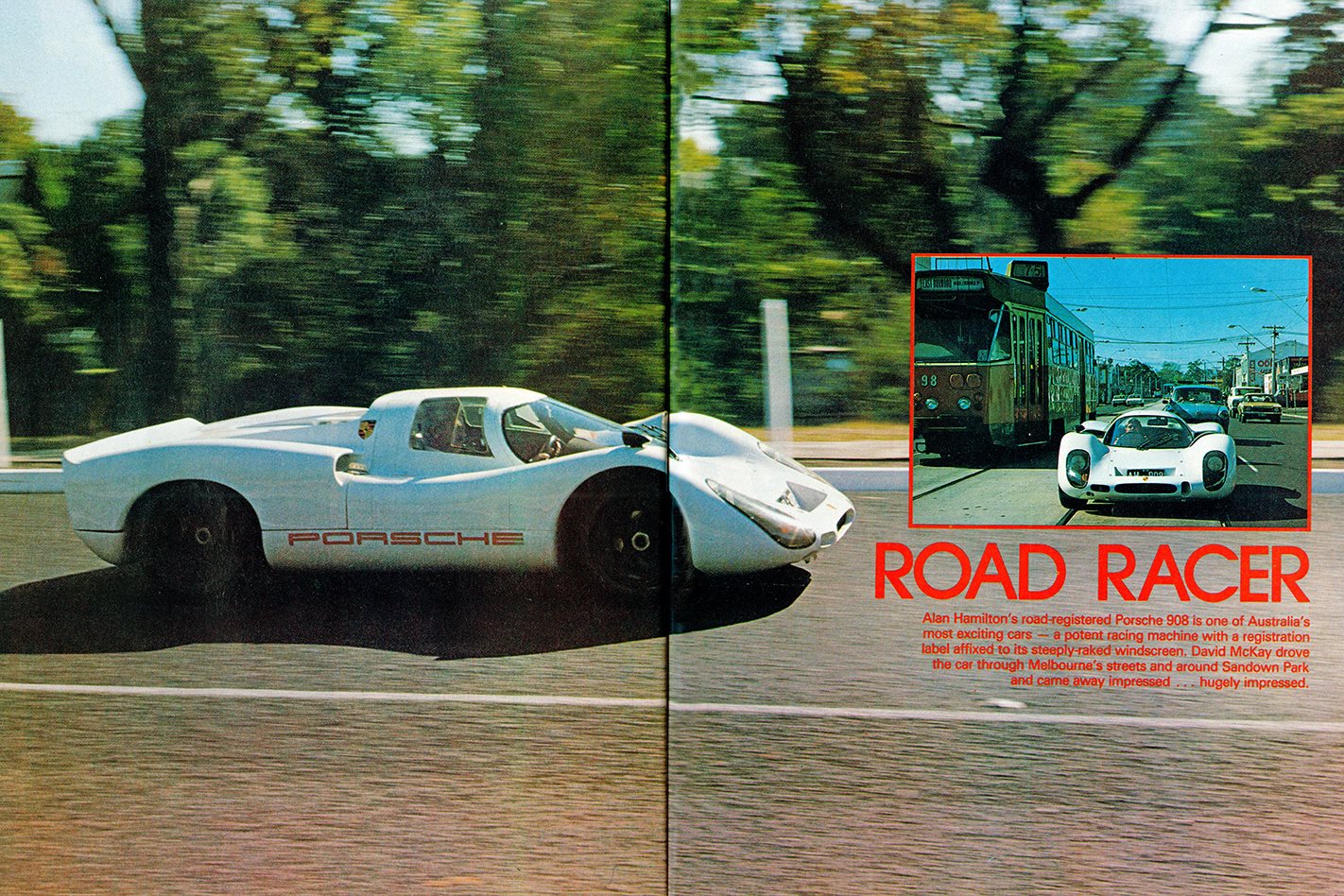

Alan Hamilton’s road-registered Porsche 908 is one of Australia’s most exciting cars – a potent racing machine with a registration label affixed to its steeply-raked windscreen.

David McKay drove the car through Melbourne’s streets and around Sandown Park and came away impressed… hugely impressed.

Road Racer was first published in the June 1980 issue of Wheels Magazine, Australia’s most experienced and most trusted car magazine since 1953.

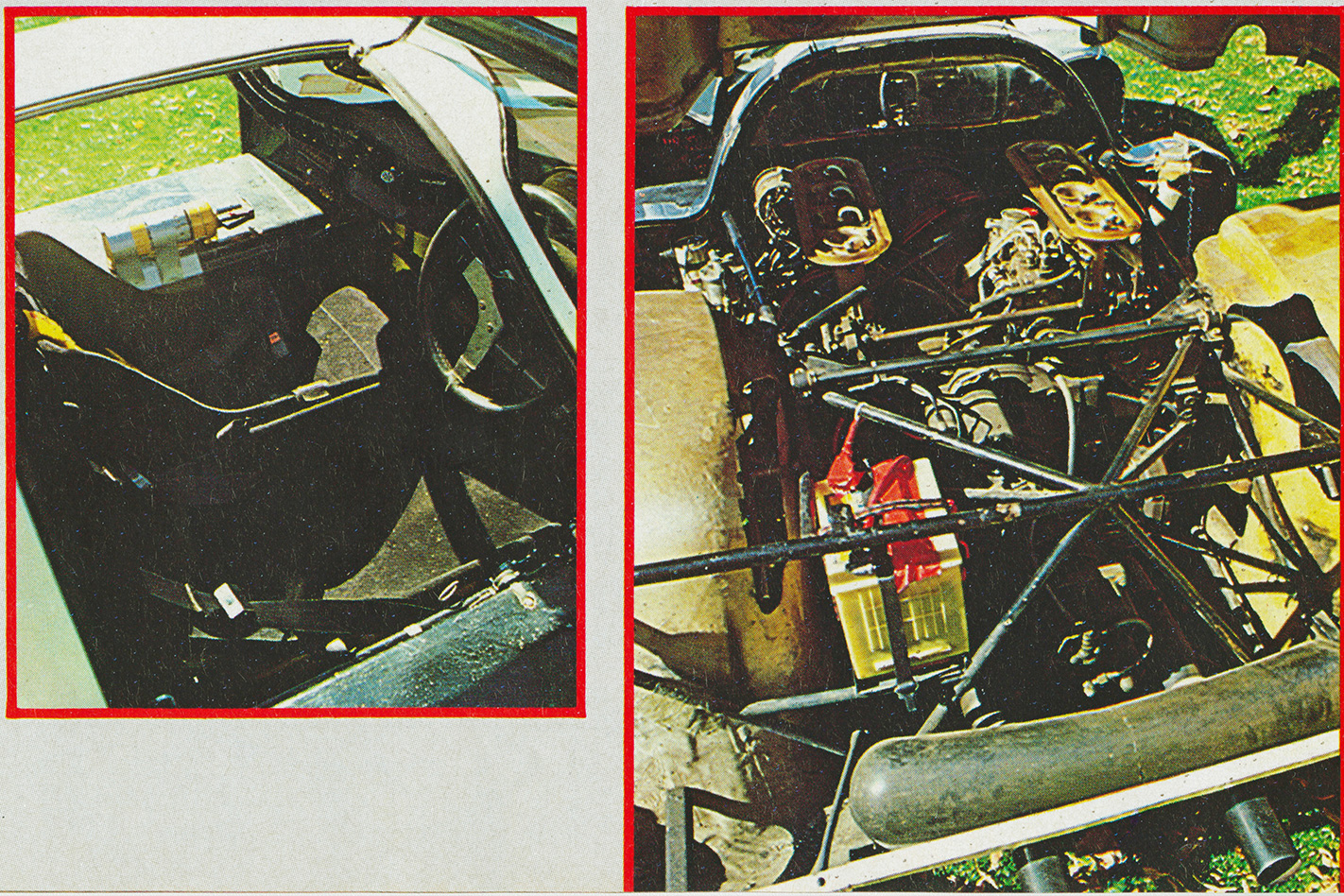

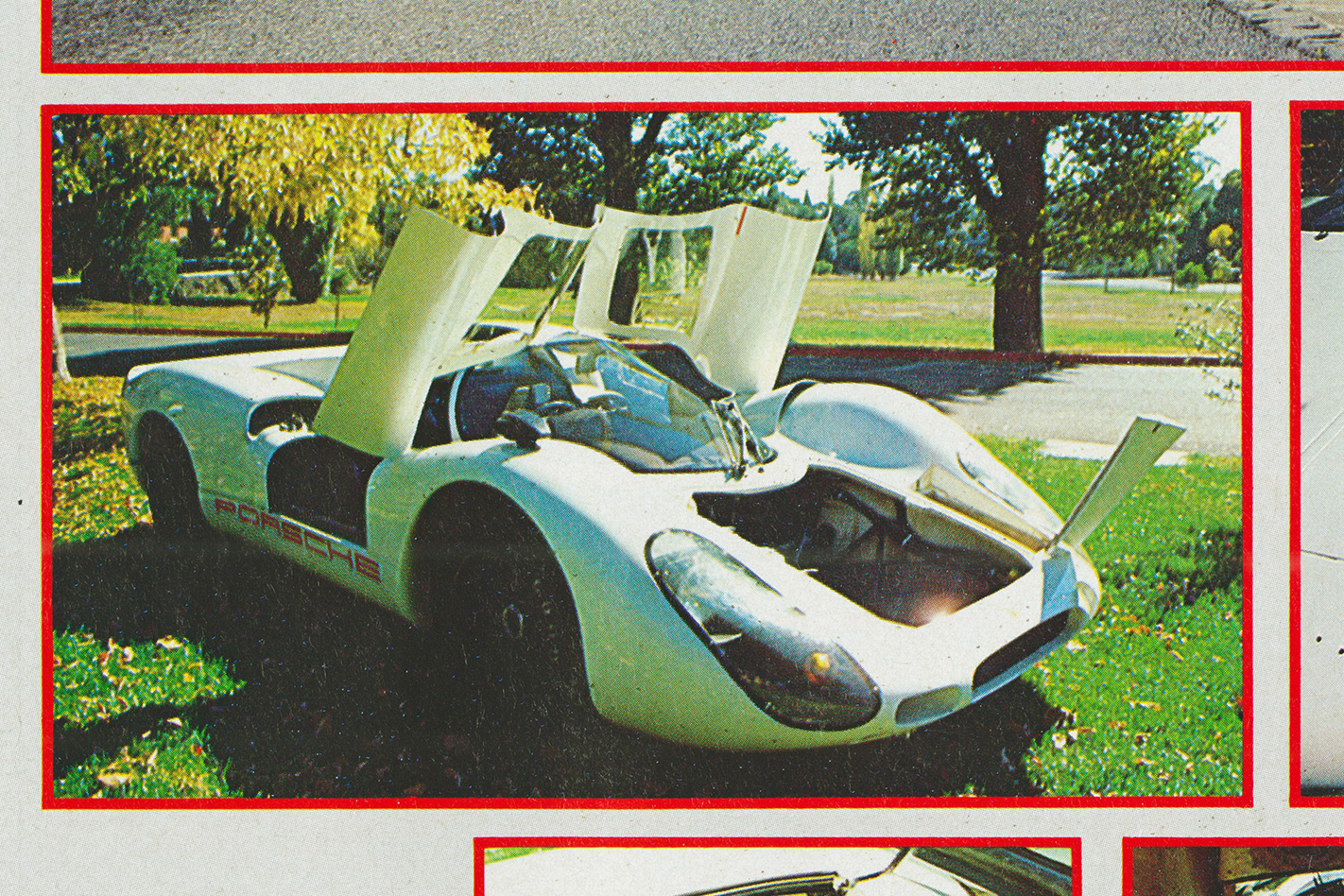

Chris Gribble of Wheels was going to ride with me and even a quick peer into the cockpit told me he was going to be very uncomfortable. Chassis number 0019 was an out-and-out racer with no frills. To the average motorist the Escort’s interior was lush in the extreme by comparison. There was no pretence at “finish” inside or out but the message was clear: this was built for a purpose – to run faster and longer than its rivals.

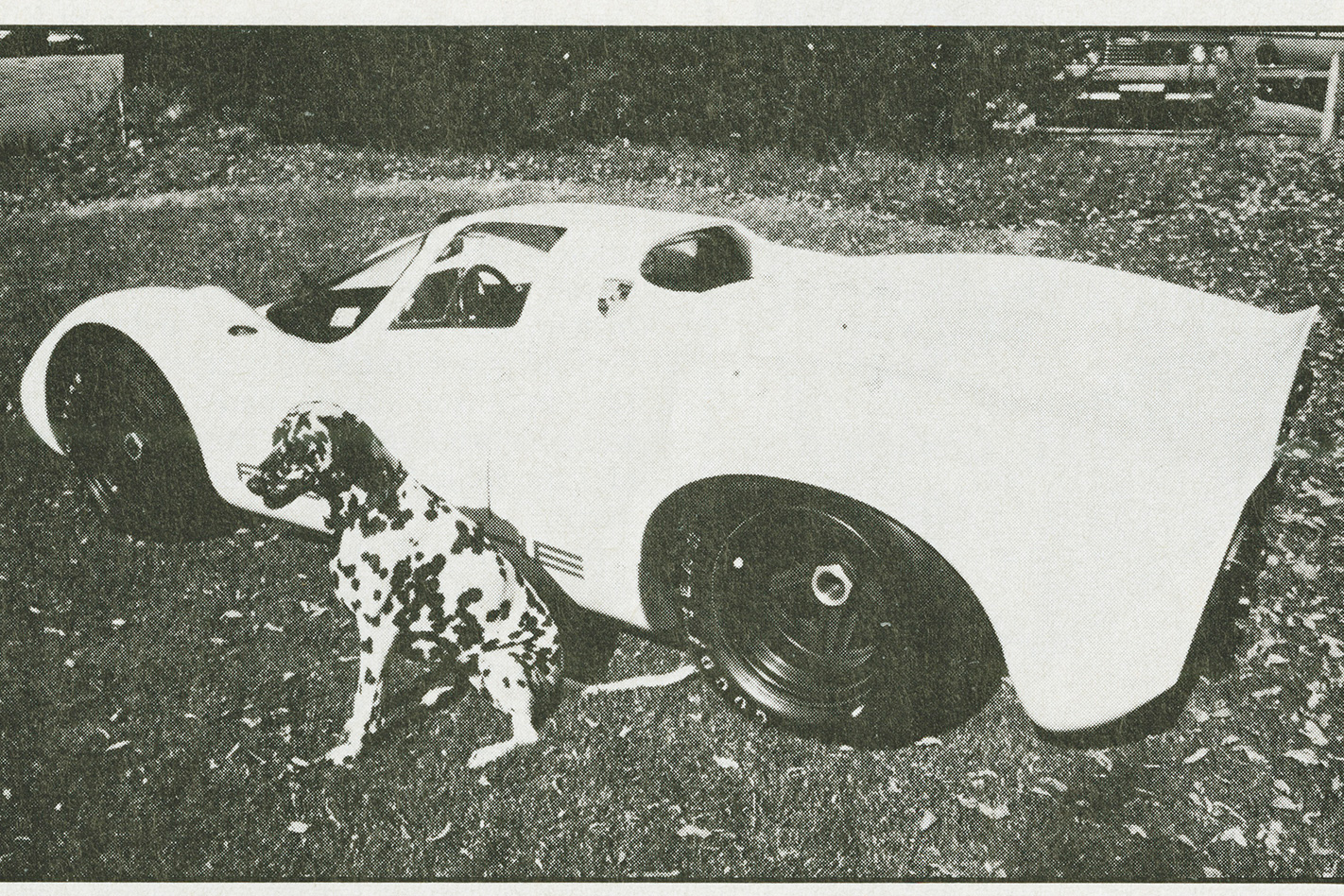

The roof line was lower than the Escort’s waist and had I not had experience in inserting myself into tiny cockpits before I would have probably slipped a disc trying. The doors swing up and forward and open to a push on a button. The sill is wide for the driving position is near enough to central and the seat made of fibreglass (as indeed is the whole body) had a skin of cloth and looked uncompromising. In fact it proved remarkably comfortable.

Hamilton had the seat well back to accommodate his larger frame and he quickly found a pillow to jack me closer to the small black padded three-spoked wheel. I was adopting the attitude first made famous by that great Scot Clark and the Lotus 25, lying down to do the work. It was going to be very hot in such cramped quarters and under the big sloping screen. When raced, these cars carried ice up front and iced water was pumped through the drivers’ suits at a flick of a switch next to the starter key.

This combated fatigue in long races and was not bad thinking 12 years ago! Ventilation was minimal at low speed; the forced air was insufficient to keep the flaps open in the side windows and the only air came by way of the sliding panel in the rear window – along with the inspiring whine of the four chain-driven camshafts.

The tits and bits are labelled in German and from left to right are: petrol pump, two ignition switches which look after the dual ignition distributor, a horn, a washer/wiper press-and-turn knob, light switch, the starter key and the aforementioned suit cooling switch and warning light carefully blacked over to allow no more than a pinprick of red light showing.

Cowled ahead of the wheel are the vital clocks and warnings. Centre is the tacho (in this case a 906 counter redlined at 7800, whereas the 908 uses 8400), oil temperature which normally runs at 80 degrees is to the left and oil pressure to the right and indicates around 7kg/cm at racing speeds. Clustered around the top of these clocks are·two warning lights for the front and rear pads, one for fuel level, one for the alternator and one for oil pressure. This latter light comes on at anything under 4kg/cm and so glows at idle and in traffic.

The pedals are well spaced and easy to operate, with a big left foot rest, and while the clutch is heavy by ordinary car standards it is no problem to dip once mobile. Naturally, the multi plates resent any fairy footing at traffic lights and prefer decisive movement and enough revs.

Hamilton gave me the cockpit drill, Chris folded himself alongside me somehow, we scraped over the gutter and off into Melbourne’s Sunday morning traffic, snarled by some extensive road works. Driving a car which has to be worth the price of a good home unit is a responsibility at any time but when it belongs to someone else and everyone seems intent on bearing down on you, all you can do is relax and enjoy it as the actress said to the bishop.

Vision through the rear 180 degrees is not good. The interior mirror was mainly filled by Chris and I am never very happy about wing mirrors even if adjusted carefully. So one has to use the trafficators diligently (ahead of the wheel on a short stalk to the left) and rely on a sudden burst of acceleration if you intend changing lanes. Once we got to Dandenong Road and the traffic was moving relatively briskly, the 908 was happy enough in fourth slot. This kept the revs under 3000 and avoided the spitting and banging that heralded the coming on song over 3500.

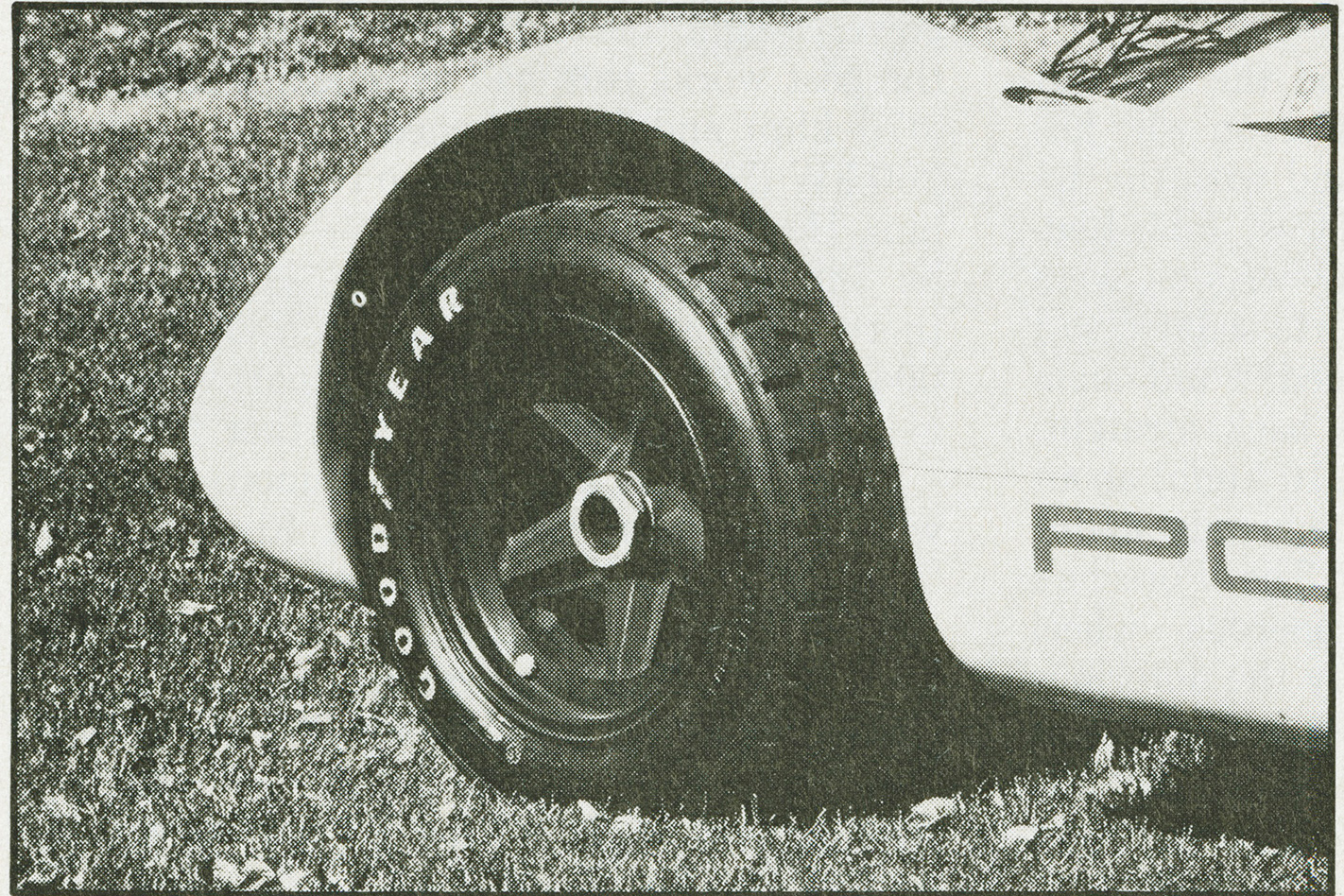

The car was shod with Goodyear wets, 25 by 15 fronts and 27 by 15 rears on 9 and 12½ inch rims. For pottering, the pressures were 23/28 and I thought the ride over indifferent bitumen better than expected. The only fault was a tendency to pull right under brakes and obviously a calliper was sticking for I never had to use the parking brake on any gentle slope. This parking brake operates with the foot brake in the same manner as those foot-operated fly-off types so loved by American car makers. The small T-bar control hides ahead of the wheel to the right.

Naturally, the car caused a deal of interest in the Sandown-bound traffic. Unlike some rare cars, there was no doubt as to its make; “Porsche” in the factory red lettering ran along both sides and across the tail while the famous shield was carried on the nose and aft of the doors.

If I were using such a car more than infrequently I would be tempted to fit a Ferrari roof periscope-type rear vision mirror and have 360-degree vision. The view ahead is superb: the two front wings channel the landscape in towards you and the road slips by underneath as though on a roller.

I was able to trundle around the track at Sandown courtesy of Bill Patterson who has sole rights at race meetings and with the approval of the Clerk of the Course, John Redpath, and stewards. The tow wagons were busy clearing up after the sports sedans, so I was perhaps wisely constrained. I did manage one quick burst up the back straight, cutting off at 6000 in fifth (210 km/h) about midway (The factory recommends above 6000 when used seriously!). The Porsche’s supple suspension with generous wheel movement was unperturbed by the notorious undulations of this part of the circuit.

It is only when you are able to enjoy the raw animal-like exhilaration of a true racing car that the time and money swallowed up in owning such a car are forgotten. It is a pity that real enthusiasts cannot line up one day and be given a quick ride in the passenger seat alongside Hamilton. Words can never adequately express the total satisfaction of feeling a fine factory racer becoming part of you as your right foot and two hands dictate the fine path between perfection and mediocrity.

Chris had asked me earlier would I like to own the 908 and I had said no for I know that I would be tempted to race it seriously and that would be foolhardy. But I did say later that I would rather own the 908 than any of the supercars of today. Regrettably, once you have driven out-and-out-racers the most exotic and glamorous road cars become a poor second best. So it might be better not to spoil the enthusiast’s dream by letting him sample a taste of pure magic. Being a passenger is not the same as driving, whatever the car.

Chris and I drove back into Melbourne through the evening, content to allow the car to potter and concerned about returning it in good condition. I had noticed a small crack on the left front wing and feared someone might have leaned on the thin skin of fibreglass. Actually it had been inflicted at the Melbourne Motor Show when a small child was perched there for a photographer father.

The sinking sun was dead ahead at one point and there are no visors in race cars. One red-faced moment was near the St Kilda end of Dandenong Road. I stalled when taking off from the lights and there was no sign of life from the battery! I fancy we had inadvertently flicked the suit-cooling switch getting out of the car at the circuit and drained the juice. It meant a push start and Chris, with his arms full of briefcase and helmet, had to struggle out and apply one Gribble power to the 908 across the intersection until she caught and fired and then scramble back in again. Thankfully, the line of cars behind was patient and well mannered.

Back safely at the works, I thought about the car while Chris set off to ring Hamilton that we were home. I think the outstanding memory was one of efficiency; the car had made it an easy day. Some racers are cranky but this little German was so purposeful about everything.

I saw the last race of the Sunoco·917/30 with Donohue at the wheel at Riverside in October, 1973. He practised over four seconds faster than the second fastest car, won as he liked and retired on the spot. Hamilton says he should have 857 kW on tap but doubts whether it can be road registered. Now that should be worth waiting for, Mr Editor!

WIDE EYES AND SMILES

By Chris Gribble

AT FIRST there is bewilderment. Then smiles, broad smiles. For some reason I’m still uncertain about, this mean, beautiful and purposeful racing Porsche brings joy to the strangest mix of people. Children smile, people who drive HR Holdens smile, even old people smile. “Young girls are blasé, though when you appreciate that they will rarely deem to even notice a car, a cool look is almost the same as a smile.

I know all this because I looked and learned from my foetal position in the passenger seat of Alan Hamilton’s road-registered Porsche 908 while David McKay conducted us to Sandown Park one Sunday morning in April. I watched as people looked down on us from their family sedans as we slid below their normal level of perception.

I watched as adult pedestrians momentarily forgot what was troubling them and smiled as we drove past. And I watched as young children shrieked their delight and boys on pushbikes did double-takes, smiled, craned to find just what this UFO was, then dropped their shoulders under the weight of their dreams. The seriousness behind the glassy eyes of teenaged boys on pushbikes still haunts me.

I can attest to all of the above. In the claustrophobia of the tiny cabin, with the urgency of the pops and crackles pouring into your ears through the small Perspex slide window and, importantly, someone else driving, you can afford to look and listen. If you can understand, there is even a great deal of enjoyment in looking and listening. There is no question of smugness or exhibitionism – though they are both bountifully there if you want them to be. In my position as observer I put more value on the fact that I could look straight into the eyes of the people; by association, the object of their fascination.

Because David was driving, I could take more notice of drivers who pulled alongside us in traffic, tore ahead, then dropped back behind us to view the Porsche from all angles. I could also more easily take stock of our observations and the mental images which are conjured with the help of the wide eyes and smiles. I distinctly remember looking at a Solo service station sign and thinking : “Yes, that’s the 908, so low”.

The very fact that the car is so low can cause problems you don’t appreciate in a sedan. The 908 was crotch-height to me, which translates to below the waist line of most cars. And drivers generally look straight ahead, not down. In the 908 you are obscured behind cars and vulnerable to people who are waiting impatiently to turn into your road from the left. In some close traffic situations you feel very vulnerable.

The stalling incident in Dandenong Road was illuminating in a way, in that none of our fellow traffic captives complained. We had stalled at the lights in the far right lane – a lane in which we were travelling because we were waiting to turn right a few streets on – and I had struggled out and given the car a push. Yet there wasn’t a horn sounded or a word spoken in anger. I suspect the people were too awe-struck to remember their traffic tempers. Maybe I’m selling Melbourne drivers short. Though I suspect I was right the first time.

Even from the passenger seat, I could appreciate that the 908 was not an easy car to drive. Melbourne traffic is the antithesis of the car’s intended function. At 6000 rpm, on a racing circuit and with a big heart the 908 would be a smooth and efficient car. On a city road, surrounded by looming cars and compelled to stay under 3500 rpm, it is an irritable and uncomfortable machine you tend to tolerate in traffic because it is unique, obviously potent and charismatic. I can speak highly of David McKay’s composure and sympatico with the car.

Perhaps the most memorable aspect of reactions to the Porsche 908 was that it literally staggered the people who knew exactly what it was. David and I could have arrived at Sandown Park in a flying saucer and been no less noticeable.

NOTES ON 908 NUMBER 0019

THIS CAR came from the research and development wing of Porsche at Weissach. Built in 1968, it was the last steel-framed chassis. The 908/2 cars had alloy frames and there had been some experimental 910 and 907 models with alloy frames earlier. The Porsche book lists the 908 coupes at 660kg but Hamilton’s car weighed in at 630 at registration. Wheelbase is 2300mm, length 4020, front track 1462, rear track 454. (The 908/2 spyders were developed at the end of 1968 and were 100kg lighter but suffered a higher drag penalty.

The four hubs and the front stubs were of titanium. Because the 908/2 models were the first all alloy frame models as a series, an air valve was fitted to the frame to pressurise the tubes and check for any cracks. Porsche continues this practice today.

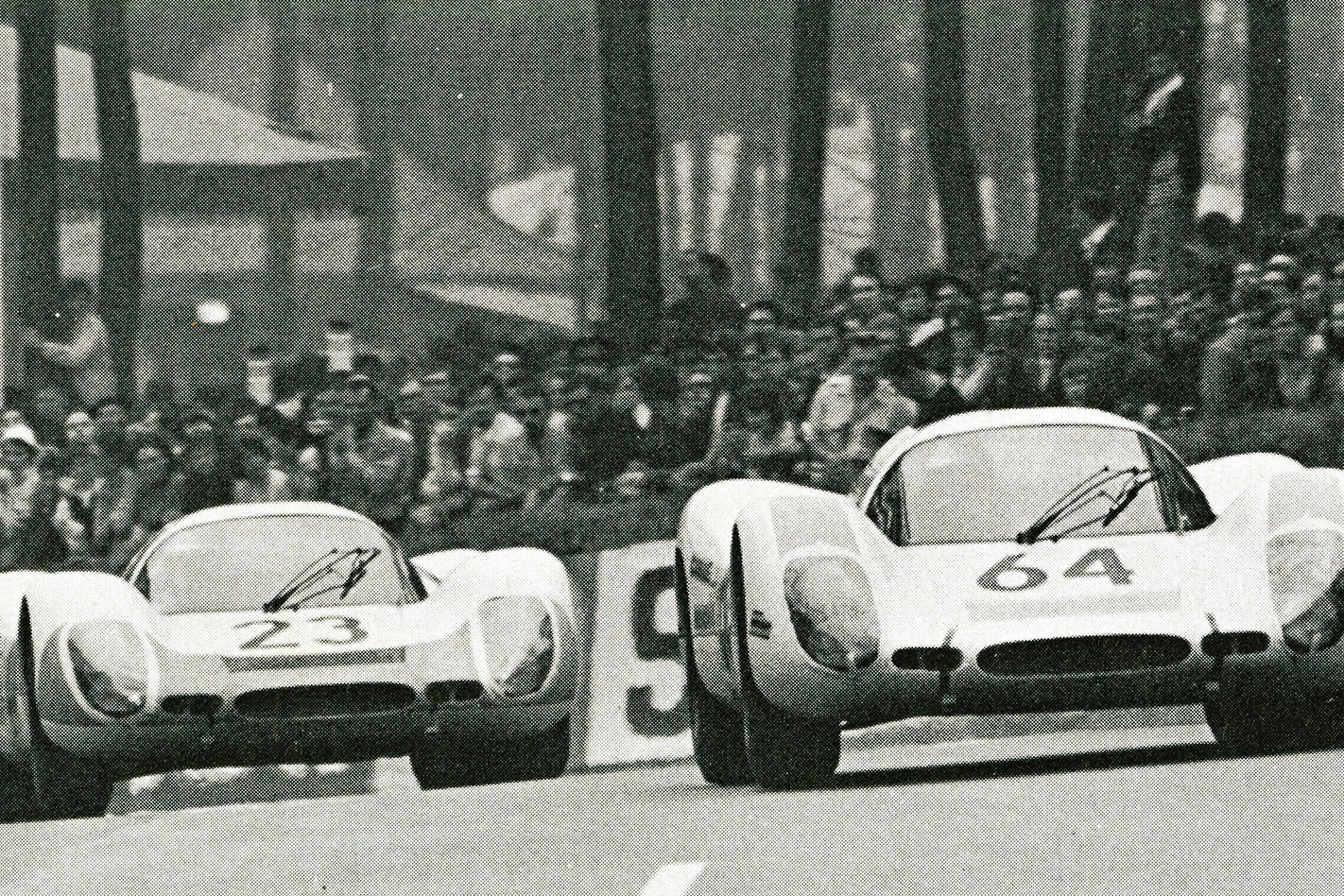

Work was started in July, 1967, on the new three-litre eight-cylinder engine (908) and it was to drop into a 907 modified chassis, the 907 itself having been derived from the 910. The first 908 (001) was a short tail version and virtually a 907, including the 907 13-inch wheels. The first appearance was at the April, 1968, Le Mans trials. The first full 908 K (short tail) with 15-inch wheels raced at the Nurburgring that year. At Le Mans 1969 the long-tailed 908s, weighing 700 kg, were reaching 320 km/h.

By the end of 1969 the 917s had matured sufficiently for the factory to race them and the 908s were sold off to private owners. The most successful of these was Reinhold Jost, who continued to campaign 908s in various guises and only as recently as March 16, this year, started from pole in the Brands Hatch Six Hours and led in his 908/3 2.1 turbo (335 kW) from the Siegfried Brunn three-litre 908/3 and would have won comfortably but for a gear linkage breakage. Brunn incidentally has made contact with Hamilton and offered him 140,000 dms for 0019. Who says gold is the best buy!

The factory developed the 908/3 for specialised races such as the Targa Florio and the 1000kms at the Nurburgring, circuits where the bigger, more powerful 917s might not be the answer. These 908/3s used 13-inch wheels and weighed only 545 kg with oil. The complete body weighed a mere 12 kg. The 908 engine took four months from drawing to assembly and gave 310/320 first time up. For the first race at Monza the engine developed 335bhp and this was to reach 370 in final tune.

The whole engine weighed 178kg. Bore and stroke were 85 and 66 mm, giving 2997 cm. The four camshafts were chain driven and the valves were sodium filled. Compression was 10.4:1 and torque was 294Nm at 6600rpm. The original transmission for the 908 weighed in at 25kg and this was considered excessive! Ultimately, a new box (type 916) with five speeds (not six) was developed with pump-operated jet lubrication. Engine vibration was cured by using a flat crankshaft.