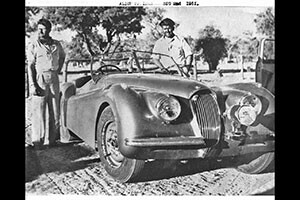

THERE IS an old and tired XK120 Jaguar that sits, half restored, in an open dirt-floored garage on the western side of Brisbane.

It has been half restored for several years, since its keepers have been busy with other things, and the car waits, watching the sun rise each morning and listening to the bird chorus in the trees. It’s at peace, and perhaps that is how it should be, for the car has had a long and curious life. There is that great day in 1951 to remember – a day that made the world sit up and open its eyes, for two men had taken this car and driven it at an astonishing speed for almost 1600 km across Australia.

The story of how that day came about, and the things that happened afterwards, is even more astonishing. In 1951, Leslie Taylor was a 35-year-old, successful motorcycle dealer in Brisbane. He was also a moderately successful racing driver, competing in a homebuilt special powered by twin Ariel motorcycle engines, a monoposto bodied MG TC, a Cooper 1100 and several motorcycles. Les also wanted to break a few records, and knew that a good road “a thousand miles long” had been built by American Army engineers during World War II, running through the centre of Australia from Alice Springs to Darwin.

Jack Murray, a Sydney-based racing driver, had set a record between the two centres the previous year, driving his 1926 Grand Prix Bugatti fitted with a worked-over sidevalve Ford VS engine. “Gelignite” Jack and a co-driver had established a time of 16 hours, and there was also the world’s highest open road average to beat. This had been set in 1949 in the Mille Miglia sports car race, when Biondetti and Salani had driven a V12 166MM Ferrari 1590 km at an average of 131.26 km/h to win the event.

And there was a chance an annual race modelled on the Mille Miglia could be held between Alice Springs and Darwin, if somebody could prove it was possible.

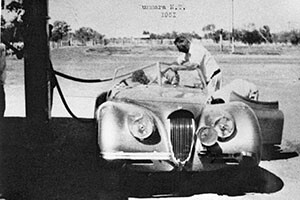

On July 6, 1951, Les Taylor bought a new metallic-bronze XK120 Jaguar roadster from the Queensland distributors, Westco Motors. It was a four-speed, drum-braked, steel-bodied car. The DOHC cast iron six developed 119 kW at 5000 rpm from 3.5 litres and would push the heavy sports car close to 210 km/h, though it was difficult to stop and steered like a truck. The Taylor XK was registered Q540-023, and Les ran it in by knocking up 1900 km. He also told his chief salesman, ex-Spitfire pilot Dick Rendle, that he was going with him for a drive.

“One day,” said Dick, now retired, when I finally met him after many months of searching, “He walked in and said, ‘How about coming along with me? We’re doing a trip in a bit of a hurry from Alice to Darwin. You’re not going to get the sack if you don’t come, but …’ A week later he bought the car, and we went.”

It was a busy 12 days. Apart from running-in the new car, a special 135-litre aluminium fuel tank had to be made and fitted in the boot, with an electric pump to transfer fuel to the main tank below. A nine-litre fire extinguisher was added to pump cold water into the radiator in case the engine showed signs of overheating; a small metal scoop was fitted at the top of the grille to deflect stones and insects and an electric siren was added to the front bumper bar. Finally, a loose tappet was adjusted.

The Jaguar was railed from Brisbane to Mount Isa, the terminal for the northwest railway, then driven along the Barkly Highway to join the north/south road at Tennant Creek, and Taylor and Rendle turned north to Darwin.

A telegram from Les sent on July 28 from Adelaide River to Frank Reid, his old friend and Castrol representative in Brisbane, implies that road conditions were not good: Slight mishap delayed here hazard greater than expected stop road not as expected conditions hot proceeding as planned without Dick … Les.

That 1600 km of “good road” the two men had been expecting to see was a narrow, sand-blown, second-class country road. It snaked between hills and gullies, dipped down to cross countless creeks and climbed mountains. The desert sands built up at the edges and spilled across the surface, and from Tennant Creek down to almost a third of the highway, the bitumen didn’t exist.

The engineers had started from Tennant Creek and worked northward, reasoning that the military didn’t need to go further south. Some of the “hazards” came in the form of unfenced cattle, mobs of kangaroos, wild pigs, wild horses, wild camels, and birds. Then, to make life even more difficult, there was an official speed limit of 65 km/h from Darwin to Tennant Creek, as the road was still technically controlled by the Australian Army.

Taylor and Rendle had travelled 3300 km to try for the record, and though the state of the road was a bitter disappointment, they were still determined to give it a go. The next day, there was another telegram to Frank Reid, this time from Darwin: Arrived Darwin stop completing arrangements confirmation here not yet available run most likely now north to south Dick due by flying doctor service may be tomorrow will advise all details may be Monday regards … Les.

At this point there’s a small mystery. Dick doesn’t remember any problems occurring at Adelaide River, or that he was flown from there to Darwin. He claims that he travelled with Les all the way, and doesn’t know why the telegrams were worded in that manner. His recollections of the rest of that trip are particularly clear, and research has failed to provide an answer.

The original plan for the record run had been roughed out in Brisbane by Les, Dick and Frank Reid. The objectives were to drive to Darwin, arrange for police permission to make the attempt, contact Department of Civil Aviation staff and confirm that departmental facilities could be used to establish starting and finishing times. Travel slowly down to Alice, checking road conditions and establishing fuel stops, rest overnight and begin the all-out effort from there.

“We worked out a 160 km/h average for the trip,” said Dick. “Frank reckoned we would have to keep at a steady 195 to 210.”

The confirmation that Les had hoped to get was a permit from the police. It was never granted. “The cops said, ‘We couldn’t sanction this, otherwise every silly bastard would be trying it’,” said Dick.

Dick Rendle’s Air Force experience was the key to DCA staff co-operation, which assured that the attempt would be accurately, though unofficially, timed. To generate more enthusiasm, Les booted the big Jaguar into a high speed run along the main runway at Darwin Airport, which was shared by the DCA and the Air Force.

“Someone said, ‘No planes flying – you’re OK,’ and off he went,” recalled Dick. “Les has never made a statement on this, or about the people who did the timing, as there was no way in the world he was going to get anyone into trouble.”

A decision was made to scrap the practice run and start from Darwin, early one morning. There was the problem of the hot northern afternoons: the Jaguar was prone to overheating and they were running out of time.

Dick remembers the eve of the event: “They said, ‘You’re bloody fools. Start early in the morning to beat the heat.’ We met the unofficial mayor of Darwin — a complete and utter buccaneer, for he had everything packed into caves. Barbed wire, crawler tractors, boxes and boxes of stuff. Born at the wrong time, he was. We spent the night with him – had a few beers and a bit of a talk — went to bed and then started.”

Almost 1600 km of rough, winding and dangerous road, with the last 530 km completely unknown to both driver and navigator. They warned the Main Roads engineers and telephoned to set up fuel stops. The tyres were pumped to 240 kPa (35 lb/in2) and the single spare checked, both tanks filled – “The petrol out there was half Standard and half kero” – and the XK120 was ready. The only concession the crew made to safety was to wear crash helmets and goggles. But, as Dick remembers, “We took the he helmets off after the first hour. Too bloody hot.”

In the strange pink and grey light that comes before the red dawn of the north, indistinct figures began to gather in small groups at the entrance to the RAAF base in Darwin: journalists, photographers, RAAF personnel and men from the Meteorological Section of the DCA, who were there to establish the precise starting and finishing times, using International Air Radio Time. Les Taylor and Dick Rendle made a brief joint statement – “We hope to complete the trip in less than eleven hours” – and at exactly 6.30, on the morning of July 6, 1951, a signal was given and the bronze XR120 accelerated into history.

In the first 320 km, the road wound through and over a succession of rolling hills, and 12 minutes from the start Taylor and Rendle hit the first of a dozen kangaroos they were to meet that day.

“They just popped like a wet bag,” said Dick, and they stopped to check for damage. At 7.15 am the Jaguar roared through the “72 mile”; Adelaide River, 116 km from Darwin, and they were averaging 155 km/h. Pine Creek was 250 km from the start and they went through at 8.20, though the sustained speed from Adelaide River had dropped to 125 km/h.

They were going well and picking up the pace when disaster struck. Not far from Pine Creek, Les slowed the car to 145 km/h through a blind corner and saw a mob of wild horses standing on the road. There was only one way to stop and Les twitched the car into a tyre melting spin. That shrieking one-and-a-half spin finished with the nose of the Jaguar buried in a bank, while the mob of white-eyed and snorting brumbies fought to escape the terrible object.

When the dust cleared, eight horses were down on the road and the left front wheel of the car looked as if it had been kicked by an elephant. The tough little horses got up and walked away as Les and Dick began to change the wheel, then found that the crash had also bent the steering rod and the lower control arm of the suspension. Using a hammer and tyre levers, they managed to straighten the damaged parts back to somewhere near normal, fitted the spare wheel and started again.

The front end of the XK was now shuddering badly under brakes, and they had a useless spare wheel. Though that forced stop had lost them 20 minutes, they still averaged 97.8 km/h over the 103 km stretch to Katherine, which included 16 km of corrugated dirt.

Refuelling in the Territory in 1951 was a slow and painful process; the petrol pumps outside the stores had to be manually primed by pulling and pushing a metre-long handle until the fuel filled a graduated glass bowl on top of the pump. The hose was then inserted into the tank, a valve opened and petrol fed by gravity from the bowl to the tank. Ninety litres — and 12 minutes – later, the Jaguar coughed into life and roared off to Mataranka Station.

Les and Dick left Darwin on run 6.30 this morning spun into bank wrecked one road wheel otherwise all OK left Katherine 9.30 stop will advise progress … Jim Cain.

Jim Cain was the Northern Territory area manager for Castrol, then known as C.C. Wakefield and Co, and had been delegated to advise Frank Reid on the progress of the record attempt. Dick Rendle was also nominated as chief photographer, and took both still shots and three rolls of movie film. “I suppose I shouldn’t mention this, but a lot of the time I was sitting on the back of the seat taking film, and we were doing anywhere between 160 and 195.”

The road was still twisting through hilly country and they were dodging stray cattle and flocks of galahs, though the greatest hazard came from the scores of “inverts” or storm drains. Often used in the construction of outback roads and cheaper than pipe-drained culverts, the inverts were 10-metre long concrete-lined hollows in the road surface, designed to allow floodwaters to cross the road without obstruction.

“The worst aspect of the whole trip was the storm drains,” said Dick. “At 130 km/h the car jumps, but at 195 the front takes off and the back comes down, and when you land the back tyres burn the paint off the mudguards”.

It was almost impossible to see the inverts until it was too late, and Les and Dick just took them as they came. They covered the 98 km from Katherine to Mataranka in 42 minutes, averaging 140.2 km/h and pushed the average to an incredible 163.7 on the road to Dunmarra, covering 224 km in 82 minutes.

Boys arrived Dunmarra 11.22 left 11.29 actual travelling time better than 160 kilometres per hour all going well … Jim Cain.

Dunmarra was the second fuel stop and far more organized. Les switched on the siren as they approached the town and the residents were ready. They shuttled the car between six hand pumps to fill the tank, gave them food and bottles of soft drink, and cleared a mass of galah feathers from the blocked radiator.

Boys passed Elliot 12.15 now just over half way … Jim.

The average had dropped back to 118 km/h. The road was difficult and they were being affected by heat and mirages – according to Dick, “You could see bloody elephants and a woman pushing a baby in a pram in front of us. Les nearly turned the car inside out for that one.”

Another problem occurred with the driver’s waste disposal system. “Les had rigged up a funnel and a tube that went out under the driver’s door,” Dick laughed, remembering the incident. “When he used it, the tube turned in the wind and he got a faceful.”

The road improved from Elliot to Tennant Creek, and they screwed the big Jaguar tight to consume 246 km in 92 minutes, averaging 160.7 km/h. The fuel stop at Tennant Creek was another quick one with the pump shuttle system used again, and the excitement was rising.

Les and Dick arrived Tennant Creek 1.47 and left at 1.52 everything excellent stop will advise when arrive Alice … Jim

For Frank Reid, sitting at his desk in Brisbane and relying on irregular telegrams, it must have been a nail-biting experience. He would have known that the most difficult section was just beginning, for the bitumen ended at Tennant Creek and the team still had the McDonnell ranges to cross, a ragged line of high peaks and tortured rock that stands to the north of Alice Springs.

There was almost another disaster not far from Wycliffe Well when the Jaguar, peaking at 210 km/h, hit an abrupt rise in the featureless road. The car was instantly airborne, flying for a heart-stopping 50 metres before hitting the ground. There was another leap like that before Barrow Creek, and again the superb driving skills of Les Taylor kept the car in a straight line.

The hazards kept coming, and they had to find a way through two herds of 600 bawling cattle that were being driven along the road by Aboriginal stockmen. Again at full speed, they raced on to Alice.

Boys passed through Barrow Creek averaging well over 160 at 3.16 … Jim.

The average wasn’t quite that good. The 225 km stretch from Tennant Creek had taken 89 minutes for a 151.9 speed. Alice was 284 km away and anything could happen.

Though the Main Roads Department had been advised of the attempt, some of their work was still going on. Taylor and Rendle, hot, tired and dirty, rushed over a rise to find that the road had turned into a slippery black skid pan. A road construction gang was using a full-width bitumen boom to resurface the dirt road, and the tar was still hot and liquid. The big 16-inch wheels picked up the sticky black soup and flung it into the open cockpit, plastering driver and navigator. They got off the road and drove alongside until the new tar ended and they could scramble back and turn up the wick for the last final effort.

Les and Dick arrived Alice 5.02 pm taking 10 hours 32 minutes for trip stop both being questioned by police at present will advise after Les rings tonight … Jim.

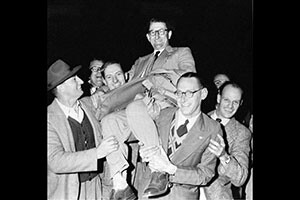

The smoking Jaguar was stopped at the town boundary by a crowd of cheering spectators, photographers, reporters and several carloads of police. Les and Dick had taken everything the road and the country could throw at them, and set a record average of 145.89 km/h for 1536.7 km. That open road record was to stand until 1955, when Stirling Moss and Denis Jenkinson teamed to drive the fabulous sports/racing 300 SLR Mercedes-Benz to victory in the Mille Miglia and a new record of 157.5 km/h. And as far as the local police were concerned, laws had been broken.

“The police let Les drive the car to the boundary of Alice Springs to set the time, and then they took him off to jail,” said Dick. The car was impounded, Dick was questioned and allowed to go free, and two hours later he arranged bail for Les, this being set at 20 pounds. They booked into a hotel and Dick was in the shower trying to scrub the tar from his hair when the telephone rang. It was someone from Jaguar in England, wanting to know about the new record.

“I couldn’t tell them much. I was standing at the phone with a towel round me, and there was this black water running down from my hair. All I wanted to do was get back in the shower.” Then there was the man who approached Dick later in the evening. “This bloke came up to me in the bar and said he had been driving a Shell van along the road that day. He had been mapping the track for places where tourists could stop. He said he knew that there was a fast car on the road, though he didn’t reckon on meeting a low-flying aircraft!”

The court was convened the next morning, with Justices of the Peace B. C. Benett and H. van. Senden presiding. Les Taylor was charged with dangerous driving, speeding, driving without Northern Territory licence and driving a car not registered in the Northern Territory.

He conducted his own defence, pleading guilty to speeding and denied that he had driven dangerously. The police prosecutor, Senior Sergeant Fitzgerald, claimed that, “Unless the police stop this kind of driving, there will be an epidemic of it! I can see no purpose being served by crackpots driving along the Stuart Highway at tremendous speed, and I will do all in my power to stop it. Not only do they endanger their own lives, which might not matter, but they are a menace to others!”

Taylor countered by saying, “I drove fast, but safely,” and added that he did not know of any road user who was inconvenienced and that he had heard no complaints. He did not charge uphills and around blind corners, and safety was considered at all times. The judgement was a fine of five pounds plus 10 shillings costs on each of the first three charges, and three pounds plus 10 shillings costs on the last charge. That amounted to 20 pounds, the exact amount of bail.

“Les got fined,” said Dick, “then we all went to the bar. The magistrates wanted to ask Les all the questions they couldn’t ask in court!” Dick maintains that half the people who helped to refuel the XK120 at each fuel stop were policemen in civilian clothes. A clipping from the Northern Standard (August 3, 1951) asked a pointed question: “Police Superindentendent Little-John would not comment this morning on Taylor’s trip or his race. Asked how Taylor was allowed to go so far before he was arrested, the Superintendent said he did not know.”

Taylor and Rendle could have been stopped at any point along that road. They had approached the police for official permission, and deliberately informed as many people as possible. There were newspaper reports before the event and radio stations broadcast regular progress bulletins. This tacit approval by the authorities and the well-timed publicity ensured that the road was almost totally free of traffic.

“We passed only four cars going either way,” remembers Dick. “Once people knew we were coming they just got out of the way, though there were people watching all along the road. It wasn’t as if the place was full of people. Virtually the only towns along the route were where we stopped for petrol. Even at Tennant Creek there were only three garages and five houses.”

And the magnificent XK120, splattered with mud and tar, looked as if it was ready to go again. The engine had used 600 ml of oil, no water and the car had averaged 3.9 km/L (11 mpg). And though the crash at Pine Creek had given the front end an extra 20 mm of toe-in, the tyres showed normal wear patterns. Taylor and Rendle left Alice the day after the record run and drove 1290 km without a break to Mount Isa. Les was in a hurry to catch a DC3 to Brisbane, as he was scheduled to drive his Cooper 1100 at a hill climb event that weekend. They averaged 106 km/h to Isa — though Les missed out on a seat and had to catch the next flight — and Dick drove the car back to Brisbane.

“Tell you what,” said Dick, “It took me nearly a month to get back to Brisbane. Everybody wanted to know about the trip. And I had to keep stopping, you see, as a lot of the road ran through private property.” The car finally arrived in Brisbane and was put on display at the Jaguar stand for the last few days of the Brisbane show. The record run had created a lot of publicity and not much else.

As far as Dick knows, there was never any sponsorship, though he thought that Jaguar flew Les to England, where he used the Vincent engine from his Cooper to power a borrowed Cooper and set a lap record at Silverstone. “As for me, just got paid for a week of doing nothing, instead of selling motorcycles.”

Les Taylor went on to race a variety of motorcars and established 14 national records at Leyburn, a disused Queensland airstrip that had been converted to a racetrack. He had planned to drive a new Fiat 1400 sedan for 24 hours, but a broken differential cut the available time in half. The Jaguar was sold to Rex Taylor (no relation); Dick left Les to set up his own business – “We were never mates” – and Taylor had marital problems.

“He left his wife,” said Dick, “Then he opened a car yard in Mount Isa. He got into some trouble with the big boys in Mount Isa and Darwin and disappeared in Darwin. At one stage, Frank Reid thought he might be in jail in New South Wales, but we never found out.”

From the records, and in the opinion of Dick Rendle, Les Taylor was an extraordinary driver: “Les was a studious type of bloke. He wasn’t an athlete, more like a Dick Smith. Les was magic behind the wheel. A lot of other people have said that, too.

“Les’s real forte was being able to line up a corner without a marker. I never saw him spin off. He raced the Jaguar at Leyburn and pushed Doug Whiteford’s Lago Talbot all the way. Whiteford jumped out of his car at the finish and raced over to shake Les by the hand. He said that he had never had a harder race.”

Like a broken racehorse, the XK120 was sold into obscurity. T. Rauchle, a resident of Leyburn, bought the car in 1953. It was never raced again, and was finally used as a hack to deliver mail over the rough dirt roads of Central Queensland. In 1968, Brisbane-based architect and motoring enthusiast Kees Heybroek went to Toowoomba in an effort to find parts for his Mark IV Jaguar. One and a half XK120 Jaguars were almost buried in long long grass behind a house, and Kees bought them on the spot. The complete car had 620,000 km registered on the speedometer, and the body had been painted by hand in red enamel.

“I had no idea,” said Kees, “That it was the Darwin-to-Alice car. I traced the registration back and discovered the history of the car when I went to the library to research 1951 articles on XK 120s. After that I found Frank Reid and he helped to prove it was the car from a photo he had of the car spinning, which showed the registration number.”

After 620,000 km, the Jaguar was tired. The engine was still fitted with the original pistons and polished crankshaft, though the suspension and drive train were badly worn. Kees and his wife Chris have been restoring the old warrior since 1971, and hope to have the rebuild finished in a couple of years. The car will be used for occasional tours, and Kees talked about trips into western Queensland and beyond. “I might even take it to Darwin and do the run again,” he says.

Dick Rendle had this to say: “It should be possible — if the road was closed, and with the support of proper pit stops — to average a hundred and seventy-five.”

I wonder?