It’s a bit hard to imagine that the people who gave us the Datsun 1600 could be the same ones who also foisted the 120Y upon an unsuspecting, largely undeserving world.Everything that was wrong with the 120Y – and there was lots – was right in the 1600.

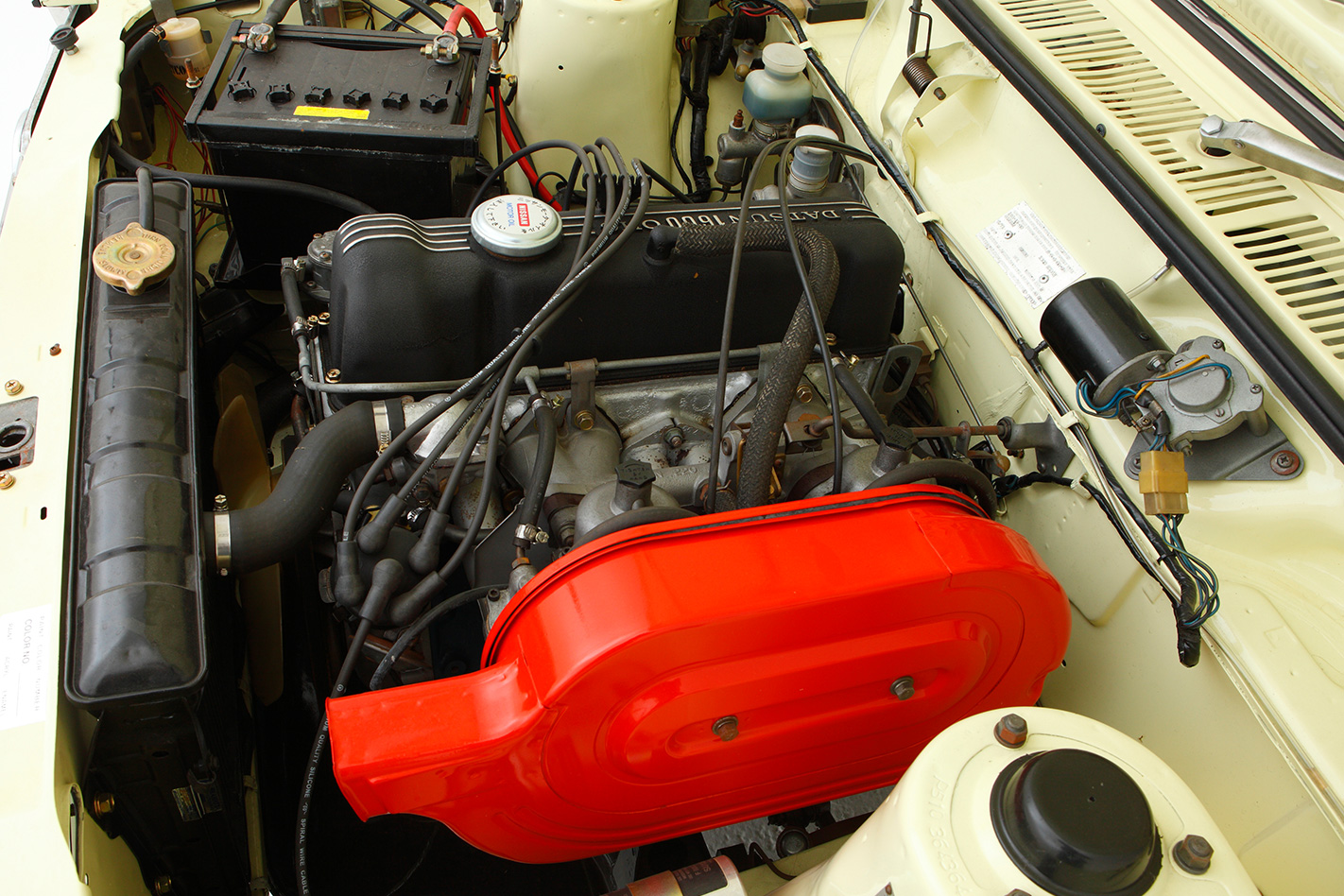

The 120Y’s horribly ugly, tinny little body, for instance, was the opposite of the 1600’s upright but handsome and rather solid bodyshell. The 120Y’s dumb-arse cart-sprung rear end was the antithesis of the 1600’s clever independent set-up. Even the wheezy, wobbly little pushrod 1171cc fitted to the 120Y was the polar-opposite of the 1600’s grunty 1.6-litre overhead cam unit.

Okay, so history is littered with examples of car-makers going backwards, but even if the 120Y had never come along like the four-wheeled plague of locusts it was, the 1600 would still have stood tall.

The 1600 was not just a great road car, either. If there’s a single rally driver who hasn’t fanged a 1600 between trees on a special stage, we’re yet to meet them. Hell, go to a club-level rally even today and you’ll still see Datto 1600s being flogged along and doing okay, too, just quietly.

Specifically, cars like the BMW 1602 and 2002 bore more than a passing mechanical similarity to the Datsun, with design elements like a semi-trailing arm rear-end, MacPherson strut front-end and an overhead camshaft engine mated to a floor-shifted four-speed manual.

But it’s equally true that a lot of those elements (mainly the engine layout and the gearbox) were handed to Datsun on a silver platter when it (or rather Nissan) absorbed the Prince Motor Company in 1966. Same goes for the front disc brakes which were something else for 1968. It would take Ford until the XB Falcon of ’73 before front discs were standard, and that was on a car weighing twice that of a 1600.

Most of the car was Japanese made and delivered in CKD (Completely Knocked Down) form, but some parts were locally sourced as Datsun attempted to keep its local (Australian) content up. The wagon was mechanically identical to the sedan apart from its rear end, which employed a live axle with leaf-springs.

While the Datto was rallied to within an inch of its life (sometimes beyond), what you might not know is that the little four-door also has an impressive Bathurst heritage. Nine of the buggers were entered in the 1968 Bathurst enduro and they all finished. In fact, Doug Whiteford and John Roxburgh took the Class B win and 15th outright, with the 1600 of George Garth and Bruce Stewart behind them, second in class.

Class B for 1969 was another Datto benefit with 1600s filling the first five positions at the chequered flag and the Dattos were back again in ’70, ’71 and ’72 with mixed results including more class wins along the way. But it was, of course, rallying where the 1600 shone brightest. Basically, the boxy little Datsun has cleaned up just about every rally title worth having.

So, you need to watch out for rust (rust-proofing was still a bit of a black art in Japan in the 60s and 70s) and 1600s rot from inside the doors, the sills, the leading edge of the bonnet, front and rear valances and around both windscreens.

The other big bodywork check is to run an eye down each flank from rear to front. Do the body creases on the rear quarter and rear door line up? If they do, great, but if they don’t you should start looking at the body where the quarter joins the rear-door opening.

Dattos have a nasty habit of cracking right about there, especially if they’ve been hammered hard over rough roads. In extreme cases, it’ll look like the boot is falling off. In really extreme cases, the boot will fall off.

Watch out for cars, too, that have worn out every moving part. It’s not that shocks, bearings, springs, bushes, brakes, clutches and such can’t be replaced, but the bill for doing it all in one hit won’t be tiny.

In some cases, a Datsun 1600 is just economically unviable. Shame, but there we are. Even then, it isn’t that simple. See, because the Datto was the dirt-road-warrior’s car of choice, a seriously high percentage of them wound up inverted, driven over cliffs and stuffed up trees. Nothing culls a model’s population like a predisposition towards motorsport.

Even if the car in question wasn’t written off by successive generations of devoted head-bangers, chances are it’ll be pretty second-hand these days. An ex-rally car won’t be hard to spot with its roll-cage-holes, chopped up dashboard where the Halda once lived, upgraded alternator and probably fat, steel rims, but even more common is the example that’s still fitted with all that gear but runs road-car rego.

A popular modification was to throw away the 1.6-litre L16 engine and install a 2.0-litre L20 unit, which was pretty much a drop-in fit. Equally popular was the next move which was to tune the L20 to produce, oh let’s see, about double or triple the power Datsun’s engineers had in mind. This can produce either a fine driving machine or, more typically, a barely controllable, pinless grenade. Your call, but at least make sure the thing isn’t going to disintegrate without a diet of Avgas.

Sure, it has a wicked reputation, but it was seriously working-class wheels by the time it was out of warranty and driven into near-extinction not long after that. Then again, the Leyland P76 has suddenly become collectible, so anything’s possible.

The Good A working stiff’s classic car. And it should be collectible into the future, too. (Probably, anyway). The 1600 is unbelievably tuneable and is still competitive at club-level motorsport. The little Datsun’s an affordable classic … for now. And it’s tough to boot, so a genuine daily driver.

The Bad Finding a non-molested, non-crashed one will be difficult. Most are like grandfather’s axe Like any mass-produced item, time can be cruel to them. Parts are becoming rarer by the day. Is the 1600 too rare to modify? It is yet to confirm its status as museum piece or just a plain good old car.