DRIVERS are just overpaid wheel jockeys, right?

The real trick to winning in motorsport is finding out how far the rules can be bent without breaking.

So, when it comes to finding tenths on the track, the boys in the pit garage – designers, engineers, strategists, mechanics – are collectively more important than the bloke behind the wheel.

Sure, the driver can make a difference, just look at the comparable performances of Vettel and Webber throughout the 2011 season. Both had the same car. One took 15 poles and 11 wins, the other managed three poles and one win.

But a driver is nothing without a competitive car, as Michael Schumacher‘s 2011 season demonstrated. And the lengths to which some teams will go to gain advantage can lead to astonishing innovations … and outright cheating.

Then there’s the grey area described as “the spirit of the rules”, but that definition often hinges on whether you’re winning or chasing.

One brilliant example of innovation was the 2010 McLaren F1 car’s F-duct. By blocking an air vent inside the cockpit with their left knee, McLaren drivers could alter airflow over the rear wing to liberate an extra 10-12km/h.

Moveable aerodynamic devices were banned at the time, but since only the driver’s leg moved, the F-duct was deemed legit. McLaren’s F-duct wasn’t enough to beat Red Bull for the 2010 championship thanks in part to the latter’s own ‘innovation’, a flexible front wing which increased aero grip in high-speed corners.

F1 isn’t alone when it comes to testing regulatory elasticity. WRC has had its share of ‘innovators’, as has America’s NASCAR series and even our own Australian Touring Car Championship.

In a high-speed world where a tenth of a second can be critical, there’s surely no motorsport category untainted.

What we’ve got here are 10 of the more interesting examples of, um, rulebook interpretation, in no particular order.

Each proves the adage that what matters isn’t how you play the game, but whether you win.

McLaren’s Spygate

Okay, so there’s really no disguising this one as innovation.

In fact, it’s the kind of ‘dark alley at midnight’ shenanigans more suited to international espionage than the glamorous world of Formula One.

Aerodynamics can make or break an F1 season.

Any advantage is potentially huge, and teams go to great lengths to keep their airflow intelligence secret.

So, in 2007 when confidential Ferrari documents turned up at the house of McLaren’s Mike Coughlin, a spying scandal erupted that eventually dragged Renault and Honda’s F1 teams into the mire.

Honda’s involvement is less sinister – or maybe we still don’t have the full story.

The Japanese manufacturer released a statement in July 2007 saying that both Stepney and Coughlin had approached the team in relation to ‘job opportunities’, and that no confidential documents had been offered or received.

History shows that McLaren copped a record $100 million fine and, while Renault was also found guilty, no fine was handed down. In addition four employees from three F1 teams were fined a total $630,000

Renault’s Singapore Fling

September 2008 saw F1’s first-ever night race, in Singapore.

Despite strong showings in practice, Renault Fernando Alonso and Nelson Piquet Jr qualified poorly, in 15th and 16th respectively. But team principal Flavio Briatore and engineering boss Pat Symonds had a plan.

They’d exploit the safety car rules which inadvertently penalised the leaders and favoured the backmarkers; pitstops were forbidden until all cars had formed up behind the safety car.

So, once the field had lined up behind the pace car, the pits were opened. Drivers peeled off and Alonso, who had pitted three laps earlier for tyres and fuel, moved up through the field to first, right behind the pace car. He went on to win the race…

The allegations didn’t come to light until a year had passed, and Benetton gave Piquet Jr the flick. In return, he spilled the beans on what became known as Crashgate, triggering the resignation – jumped or pushed? – of Briatore and Symonds.

Renault’s punishment – banning from F1 altogether – was suspended for two years pending further rule infringements.

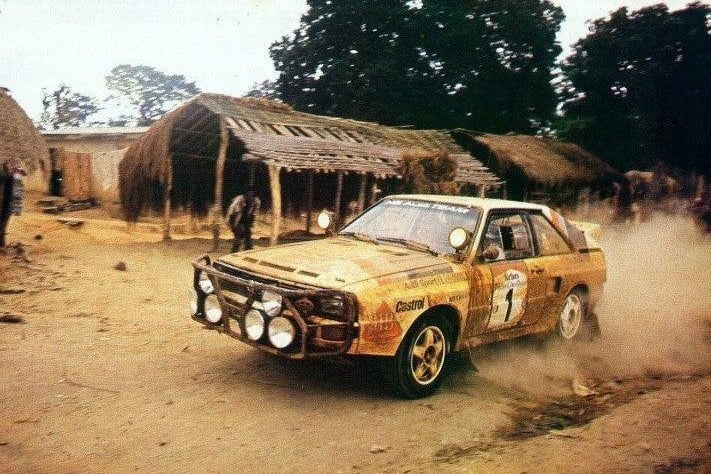

WRC swap-meet

In 1985 WRC cars did not carry TV cameras, and helicopters didn’t shadow competitors across stages.

Audi works driver Michelle Mouton started an Ivory Coast WRC stage with a seriously ill Audi Quattro – and engineer Franz Braun’s mechanically-similar support car right behind.

Accusations later flew not of a wholesale engine swap, but of a wholesale car swap; the race car’s panels had allegedly been transplanted onto the healthy support car’s chassis and mechanicals. Presumably somebody later went back to pick up Braun and the lame rally car.

Penske and Donohue take a bath

Indy 500 winner and hugely successful American Trans -Am championship driver Mark Donohue had a strong 1967 season in his Roger Penske-owned Chevrolet Camaro Z-28.

He won three races that year, but it was his massive win in the last race – he lapped the entire field – that raised eyebrows. It turned out they’d been dipping the car’s frame in an acid bath, making it 110kg lighter than the 1250kg class minimum. As a result, Donohue was disqualified.

During design and construction, teams pare the chassis back to below the bare minimum then add ballast back in, usually at the lowest central point within the chassis, to benefit the centre of gravity and to bring it back up to regulation weight.

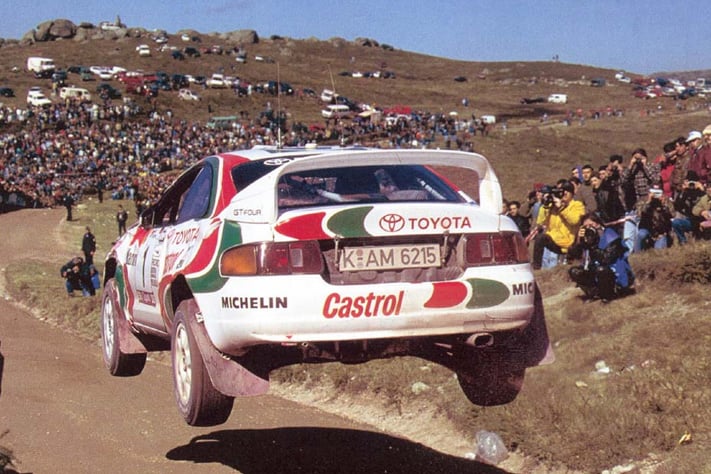

Toyota’s trick turbo (de)restrictor

Back in 1995, then-FIA president Max Mosley called it “the most sophisticated device I have seen in 30 years of motorsport.”

Toyota’s 1995 WRC effort was handicapped by the corporation’s insistence that the race car be based on the Celica, not smaller hatchbacks as other teams were doing.

In the same year turbo restrictors were required to regulate airflow to the turbo.

Toyota’s restrictor had a clever bypass mechanism that let in more air and therefore realised more power, by some estimates as much as 37kW more than the standard 224kW.

So, when scrutineers undid the clips to remove and check the turbo and restrictor, they were also unwittingly closing, and therefore concealing the illegal bypass.

The system clearly worked. Despite the handicap of an uncompetitive chassis, Toyota drivers filled out two of the top four positions in the championship. The (de)restrictor was eventually discovered on Didier Auriol’s car at the Catalunya Rally.

Toyota received a 12-month ban, and drivers Auriol, Juha Kankkunen, and Armin Schwarz were stripped of all points and disqualified for the rest of the season.

Brabham’s ‘water-cooled’ brakes

By 1982 the turbo era had begun, but few teams could afford the expensive technology. So, many stuck with the naturally-aspirated Cosworth V12 rather than the turbo V8s.Unable to compete on outright power, the V12 teams found another way to improve power-to-weight.

Lotus designer Colin Chapman is credited with the idea, but Brabham’s Nelson Piquet arguably put ‘water-cooled’ brakes to best use, winning the ’82 Brazilian GP … temporarily.

During the early laps, the water was dumped from the ‘brake reservoirs’ – some say 60 litres, roughly 60kg – making the car lighter for the duration of the race.

Post-race, the teams topped up all fluids as the rules dictated, including the now empty water reservoirs, thus meeting the minimum weight requirement.

However, both Piquet’s car and Keke Rosberg’s second-placed Williams, were later disqualified, after a protest from turbo-powered, new ‘winner’, Renault.

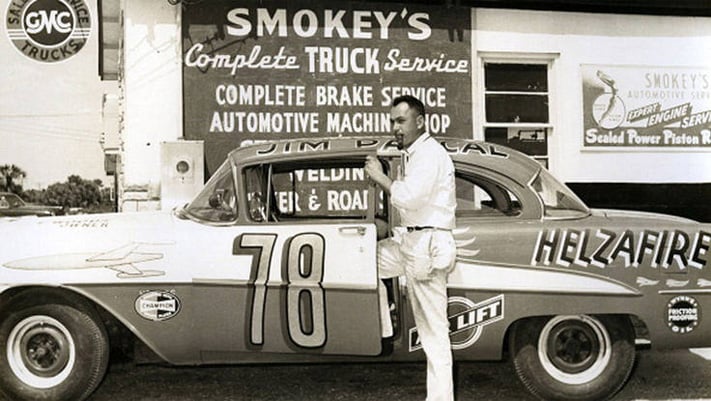

Smokey Yunick’s groundbreaking brain

Americans consider Henry ‘Smokey’ Yunick the godfather of Motorsport ‘innovation’. Smokey was a car mechanic and designer during the early years of the NASCAR scene in the 1950s and ‘60s, a time when rule books were not exactly comprehensive.

Some of his early innovations included 1959’s Reverse Torque Special, running an engine in the opposite rotation to normal, and the 1964 Hurst Floor Shifter Special in which the driver sat alongside the engine and fuel tank in side-car style pod. Clearly, he wasn’t afraid of thinking outside the square.

Some of his modifications weren’t actually cheating, but subsequently triggered rules banning their use, such as lowering the roofline and raising the floor to reduce aerodynamic mass.

After that was discovered, he boosted capacity with three metres of superfluous fuel line.

In 1962 open-wheeler racing was forever changed when he put a wing on Jim Rathmann’s car. The wing gave the car an incredible advantage in the corners, but made it so slow on the straights, its lap times were reduced. Yet the seed was sown…

Smokey probably did more to keep the rule-book writers busy than any other motorsport identity.

Brock’s last Bathurst

No one knew it at the time, but Peter Brock’s ninth victory at Mount Panorama would be his last. It would also be remembered because Brocky didn’t actually finish first.

The 1987 James Hardie 1000 was the eighth round of the inaugural World Touring Car Championship, and the Bathurst grid was flooded with international teams and cars.

Soper won the race from Niedzwiedz, with local hero Brock a distant third, three laps behind. But irregularities were found with the Sierra’s front wheelarches, which had been modified to fit taller rubber.

Appeals dragged on well into 1988, and were eventually dismissed, giving Brock his ninth and final Bathurst victory.

Schuey’s unchecked, er, desire to win

Michael Schumacher is a seven-time world champion and one of the greatest drivers of all time. He also had a nasty habit of orchestrating championship results.

In 1994 he deliberately drove into Damon Hill in Adelaide, forcing both to retire and handing himself the championship.

In 1997 he and Jacques Villenueve were separated by one point in the championship with one race to go, at Jerez.

The FIA later found Schumacher guilty of driving Villenueve with the intention of ending both their races, and disqualified him from the results and the championship, which Villenueve had already won by finishing third.

In 2002 his team-mate Rubens Barrichello slowed on the last lap of the Austrian GP to let Schumacher take the win – on team orders.

The crowd booed the podium presentation, a situation Schumacher ludicrously tried to fix by placing Barrichello on the top step.

Nuvolari and the day the fix was in

According to a 1958 book by Mercedes-Benz’s legendary team manager Alfred Neubauer, one of Formula One’s great names, Tazio Nuvolari, had been involved in race-fixing.

When a wealthy fan promised rival driver Achille Varzi a large sum of money if he won the 1933 Tripoli GP, Varzi smelled opportunity.

He went to Nuvolari and cut a deal for part of the windfall if he let Varzi win. Nuvolari in turn included their main competition, Baconin Borzacchini and Giuseppe Campari, reducing his share but increasing the odds of payday.

At that stage Campari led, until his engine suddenly ‘failed’. He celebrated his terrible luck with a bottle of chianti while the race continued.

With just two laps to go and Varzi in third behind Nuvolari and Borzacchini, the latter lost control of his car and crashed out. With a Stephen Bradbury-esque win edging closer, all that remained was for bad luck to befall Nuvolari.

And, would you believe it… with the finish line in sight, Nuvolari’s car ran out of fuel.

Varzi may have won the race, but many drivers shared in the spoils that day.