THINK I’m about to lose feeling in my right leg. I’ve been strapped into one of only three Hyundai i30 N TCR cars in the country, and the belt of the racing harness pressing me into the seat feels like a hot iron as it pinches my flesh. I try to hide the pain spreading through my thigh like a flash flood as the engine fires into life, and the door is closed with a solid THUNK.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. The reason why circulation is being cut off in my leg is because I’ve convinced HMO Customer Racing to allow me behind the wheel of its box-fresh race car which is based on our hot hatch benchmark, the Hyundai i30 N. Handy, then, that I’ve brought along a road car to join in on the day’s antics.

TOURING car fans of a certain vintage will understandably be sceptical about the introduction of TCR, which harks back to the touring car wars of the 1990s. During that tumultuous time, tin-top racing was divided into two distinct camps, with Super Tourers trying to use European manufacturing might to uproot the V8 muscle of the ATCC. Ultimately, it was the ATCC that won out, clearing a path for the local domination of what we now know as Supercars. While the key plot points have returned in 2019, the players involved this time round are eager to avoid history repeating, on the surface at least.

TCR stands for, rather literally, Touring Car Racing, and is the brainchild of Italian Marcello Lotti, who also founded the World Touring Car Championship. While he may have taken naming lessons from Australian colonisers, Lotti is thought of as a tin-top racing management genius in Europe. He and his right-hand man, Nunzia Corvino, were let go from WTCC following a ‘difference of opinion’ with the commercial rights holder on how the category should be run. Lotti’s latest creation has boomed since its inaugural season in 2015, replacing the WTCC in 2017, and invading Aussie shores in a seven-round championship for this year.

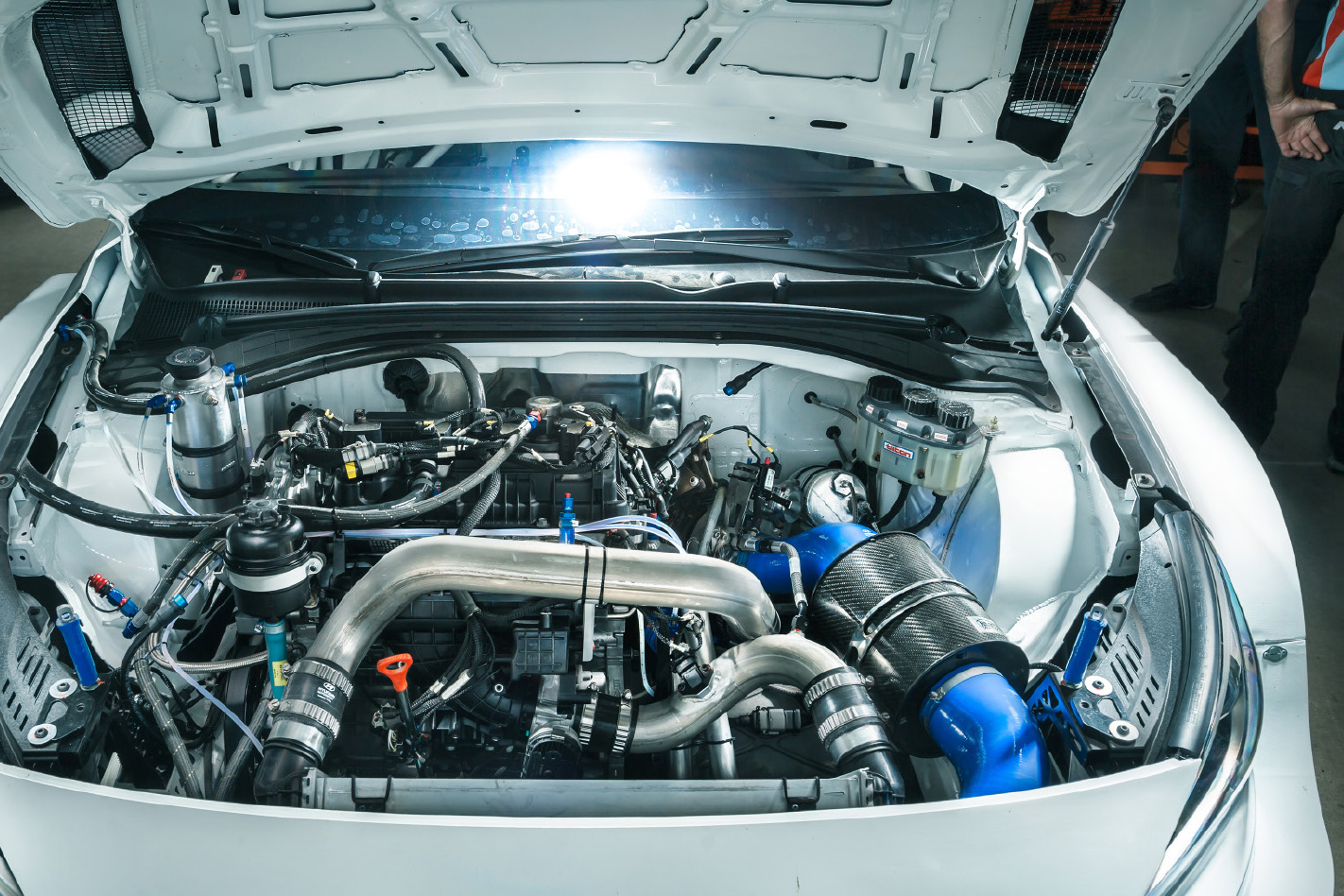

The formula for TCR is simple, with C-segment hatchbacks (and some sedans) the basis for each racer. Starting life as a production chassis, a 2.0-litre turbocharged four-pot sends power to the front wheels via either a production-based or bespoke racing gearbox (the former receive weight concessions). The homologated cars are built by manufacturers and sold to teams and are subject to Balance of Performance testing similar to GT3 racers. The rule book specifically outlaws outright factory entries.

Australian Racing Group (ARG) has been anointed by CAMS to control the commercial and promotional rights to TCR in Australia. ARG is managed by Matt Braid, who was formerly managing director of Volvo Cars Australia and of Supercars. Former Supercars CEO James Warburton joined ARG earlier this year as a non-executive director, adding extra clout to ARG as a category manager, which is also launching the new retro-inspired S5000 open-wheel category.

While Braid is quick to note that TCR doesn’t have ambitions to become a Supercars rival, it’s clear the arrival of the booming series has Australia’s biggest category worried. It’s alleged that pressure has been applied internally at Supercars to prevent star drivers dabbling in the new series, and TCR has been blacklisted as a support category at some of the country’s biggest events.

A total of 17 TCR cars from eight manufacturers are in Australia, with plenty of familiar names running teams and performing driving duties. Garry Rogers Motorsport has a four-car outfit, likewise Kelly Racing. Supercars veteran Jason Bright has started a team, and rally ace Molly Taylor has been lured from dirt to tarmac to compete in a Subaru.

All too often new categories in Australian motorsport are overhyped or underfunded, resulting in disappointingly short half-lives. It seems TCR, with the experienced heads of ARG at the helm, is doing its best to become a legitimate staple of the local racing fan’s diet, inking a free-to-air TV deal which dovetails with live streaming, while becoming a main feature at Shannons Nationals events.

BEFORE I’m unleashed in the TCR car, it’s time to take the Hyundai i30 N road car for a spin on track, and there’s a 911-shaped twist. A number of Porsche Carrera Cup teams are also testing at Wakefield today, meaning I’ll need to keep an eye on the mirror to ensure I don’t return the car to Hyundai’s head office with a Porsche badge embossed on the back bumper.

Hyundai Australia’s official N tech guru Geoff Fear got wind of our plans and has snuck into the garage to watch. He recommends winding all the i30’s drivetrain settings to kill, but keeping suspension in its softest mode. He says the extra compliance will allow the car to roll onto its outer tyre, and get the rubber to ‘hook up’ easier. Fear has overseen countless development and testing miles of the i30 N at this very track, so I’m not about to ignore his advice.

On the road, the i30 N is one of the most accessible and fun performance cars around. I’ve felt more comfortable pushing the Korean hot hatch on public roads than something like a GT-R Nismo. However, when presented with a race track the secret to a quick lap is patience.

On the relatively tight Wakefield Park, the i30 N is a hoot, however like any front-drive hatch speed management is vital to managing the grip on offer. It’s easy to barrel into a corner with more velocity than the front treads are prepared to deal with.

While it’s no porker, the i30 N road car’s 1429kg is much more apparent on the track. Brakes and tyres are punished and past their best after only a handful of laps. Though Hyundai’s five-year warranty for the i30 N covers track use, the car was never intended to suffer extended circuit abuse, so it’s time to give it a breather, peel into pit lane and squeeze into some Nomex.

ALTHOUGH it starts life as a basic i30 body-in-white, it’s clear the TCR version is a much tougher beast. A lowered ride height plus the foursquare stance of flared arches cut an intimidating figure even in the stark white paint used for testing. Each wheel is shod with 18×10-inch slick Michelins but unfortunately there are no tyre warmers on hand for the day, so the responsibility for getting the rubber up to working temperature is all mine.

“Don’t worry about weaving, your best friend heating up the tyres will be the brake pedal. Just slam it,” is the advice given by Nathan Morcom, the car’s regular pilot, before sending me out on track.

With visions of spearing off at the first turn running through my mind, I spend my initial lap heeding Morcom’s instruction. Accelerate. Brake. Accelerate. Brake. Gentle at first, but then with increasing ferocity.

The monotonous process allows me to recalibrate my brain to the brake-pedal force needed to maximise the TCR car’s stopping power.

Discs are enormous: 380mm ventilated steel units up front, clasped by four-piston calipers, while the solid rear discs are 25 percent smaller at 278mm. Morcom, who spent two seasons in Super2 after winning the Australian GT Endurance Championship, likens the TCR car’s braking ability to that of our home-grown Supercars.

As my confidence builds, more committed braking attempts require almost all the force I can muster through my leg. Even with the belts fastened to make it feel like my ribs are cracking, a forceful stop is like the hand of God slapping me on the back, forcing me forward in the seat. Even my most ambitious stomping of the brake pedal can’t cause the front tyres to lock, even despite no ABS.

It’s on my third lap of the Wakefield circuit I realise that something is a bit … off. While there’s nothing mechanically wrong with the car, there’s something my brain can’t quite comprehend. Aren’t race cars meant to be fearsome beasts, ready to bite your head off and spit you out at the smallest provocation, and tamed only by an elite few with rare talent? It seems that cliché doesn’t apply to Hyundai’s racer, which is encouraging me to push harder and carry more speed.

There’s no traction control – this is still a proper racer – but the car supports you in the pursuit of speed, instead of fighting it. Even with 257kW and 460Nm thanks to a larger turbo, beefier internals and a racing ECU, Hyundai’s TCR car is never going to win a power war, but it’s a decent step up from the road car’s 202kW and 353Nm, and certainly potent enough to prompt the slick tyres into wheel spin with a vicious prod of the accelerator.

A more progressive application sees the front-drive racer just grip and go. The front axle is more than capable of performing both power-delivery and steering duties thanks to the fitment of a more aggressive front differential, as the i30 shoots from the apex with no protest from the wheel.

Steering the i30 TCR doesn’t require forearms like tree trunks, due to an electrically assisted rack and pinion set-up which, while mechanically similar to what is found in the road car, features a massive change to the steering ratio. Turn-in is almost neurotic, thanks in part to the ultra-quick rack – just a single turn lock-to-lock – meaning precision and finesse are essential when working the Alcantara-clad wheel. The powerful combination of slick rubber and clearly functional aerodynamics means the car is able to maintain mid-corner speeds the road variant could only dream of. The nose of the car darts towards apexes with manic intent, the large front splitter and rear wing keeping it hunkered down.

In the transformation from road to race, the i30 N’s suspension hard points and layout haven’t been changed, but the components are all beefed up. Under the front arches is a MacPherson strut set-up, with coil springs and gas-filled dampers (the team were testing both Öhlins and Supashock units on the day), while a four-arm multi-link axle combination underpins the rear. Gears in the six-speed Xtrac sequential are shifted without a clutch, using steering wheel-mounted paddles, each change of ratio accompanied by a sharp BANG from the exhaust.

It’s a hot day, so driving the TCR car is a punishing experience. Brilliant, but punishing. Just a couple laps in and I’m dripping with sweat. Time to hand back the reins, and ponder how Hyundai’s German engineers transformed a body-in-white road car chassis into a racer with the most genial attitude.

Acceleration claims are nothing exceptional in race-car terms, but it’s estimated a TCR car will crack 100km/h from a standstill in approximately 5.2 seconds thanks to a fiendishly complex launch process. Wheels performance-tested the i30 N road car last year, measuring a 6.4-second sprint to 100km/h.

Over a single lap of Wakefield Park, with Nathan Morcom driving, there is a 10-second gap between the road car and racer. But perhaps more interestingly, a mere mortal like me is able to get closer to the professional benchmark in the TCR car than the road car.

This largely comes down to the set-up of the TCR car, which just wants you to go faster, encouraging more commitment with every lap, where the road car fights back, waving that white flag named understeer when it isn’t treated with the finesse of a professional.

When the data is downloaded from the car, it’s clear I’m not going to earn a race seat any time soon – Morcom is a full six seconds down the road from me. But for broader context, my best time after a handful of laps is on par with Warren Luff’s benchmark figure in a 997-gen Porsche 911 GT3.

It’s all well and good letting a racing-crazed journo loose for a couple of laps, but the real test for the Hyundai i30 N TCR will be on the track, against a full field of competitors that are all frothing at the mouth in a rabid hunt for victory. As we went to print, HMO Customer Racing’s Will Brown had won two of the three races from the opening round of TCR Australia, and nabbed a podium in the other. Not bad at all.