LESS than a second. That’s how long a highly-strung engine lasts if it loses oil pressure at full chat, so it’s vital that a modern sports car’s lubrication system is capable of sustaining whatever gets thrown at it.

While the traditional ‘wet sump’ has served in high-performance applications adequately for decades, the increasingly athletic ability of serious road cars has called for the next step up in lubrication.

Like many innovations in the most potent road cars, the ‘dry sump’ finds it origins in racing and a growing number of showroom models including the HSV GTS R W1, Mercedes-AMG GT, Ferrari 488, Lamborghini Huracan Performante, Porsche 911 GT3 RS and Aston Martin V8 Vantage have all employed the technology, but why?

If the vital oil supply surges away from the oil pump pick-up, starvation can occur and that can lead to your engine being transformed into a big, useless, solid lump of frozen metal. It’s an expensive way of sourcing a new coffee table for the rumpus room, let’s put it that way.

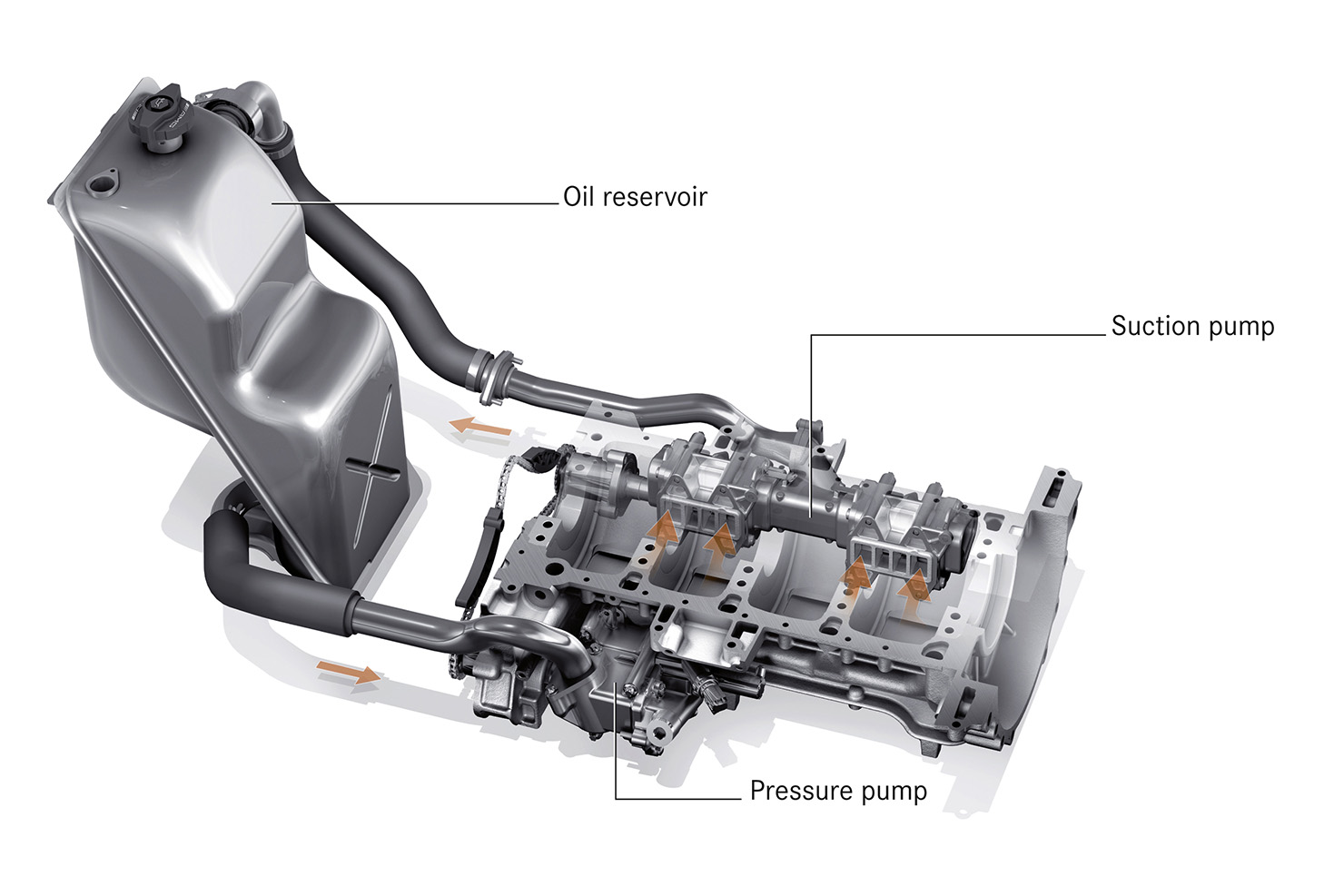

At least two pumps are required for any dry-sump lubrication system, although many employ several scavenge pumps to recover oil from the pan more efficiently. A de-foamer is also commonly used to remove air from the oil before it is recirculated, while a cooler is also often placed in the system to remove heat from the oil and engine.

The advantages are many. The reservoir guarantees a supply of oil to the engine irrespective of the G forces acting on it and is far more effective than baffling a wet sump which, in some circumstances, can exacerbate starvation.

Dry-sump systems also incorporate a crank-case pressure control valve, which prevents a spiking of crank-case pressure under extreme loading and speed. Wet-sump systems are relatively hard to regulate and have a greater tendency to compromise oil seals when pressurised.

The external reservoir allows a greater capacity of oil to be stored (10 litres in the case of the HSV GTS R W1), which increases the amount of time the oil can be cooled and reduces the risk of a low oil level.

Power advantages are also possible by reducing losses experienced by the viscous resistance of the oil on moving components such as the crankshaft and pistons. The remote reservoir allows it to be located almost anywhere under the bonnet.

As with any engineering decision, there are nearly always compromises, but dry-sump lubrication has only a few, including the most obvious – cost. The system is more complex and requires more hardware which will affect the bottom line of any car.

Other than that, a few potential minor problems regarding oil starvation to components that would normally be ‘splash lubricated’ by a wet sump can be easily solved and are far outweighed by the system advantages.

With its clear benefit to performance and reliability, you can expect to see more dry sumps under hot cars on these pages soon.