Sir James Dyson has a Hawker Harrier jump jet in the car park of his Hullavington HQ in Wiltshire, UK.

Some wags have suggested that it’s back up in case the hand dryers in the staff toilets go on the fritz. The truth is a lot more poignant given Dyson’s shuttering of its electric car business.

The Harrier is there as a reminder of what happens when you lose your corporate resolve. British engineers developed an amazing concept and then meekly surrendered it to Boeing. It sits there as a testament to fiscal short-sightedness.

There is no shortage of commentators looking to put the boot into Mr Dyson. He’s made himself an easy target. An ardent Brexiter, Dyson announced in January of this year that the company was to move its headquarter from Malmesbury to Singapore, itself hardly a vote of confidence in the prospects for post-Brexit Britain.

Now 523 jobs will be lost from the vehicle development project.

“This is not a product failure, or a failure of the team, for whom this news will be hard to hear and digest,” Sir James wrote. “We have tried very hard throughout the development process, we simply can no longer see a way to make it commercially viable.

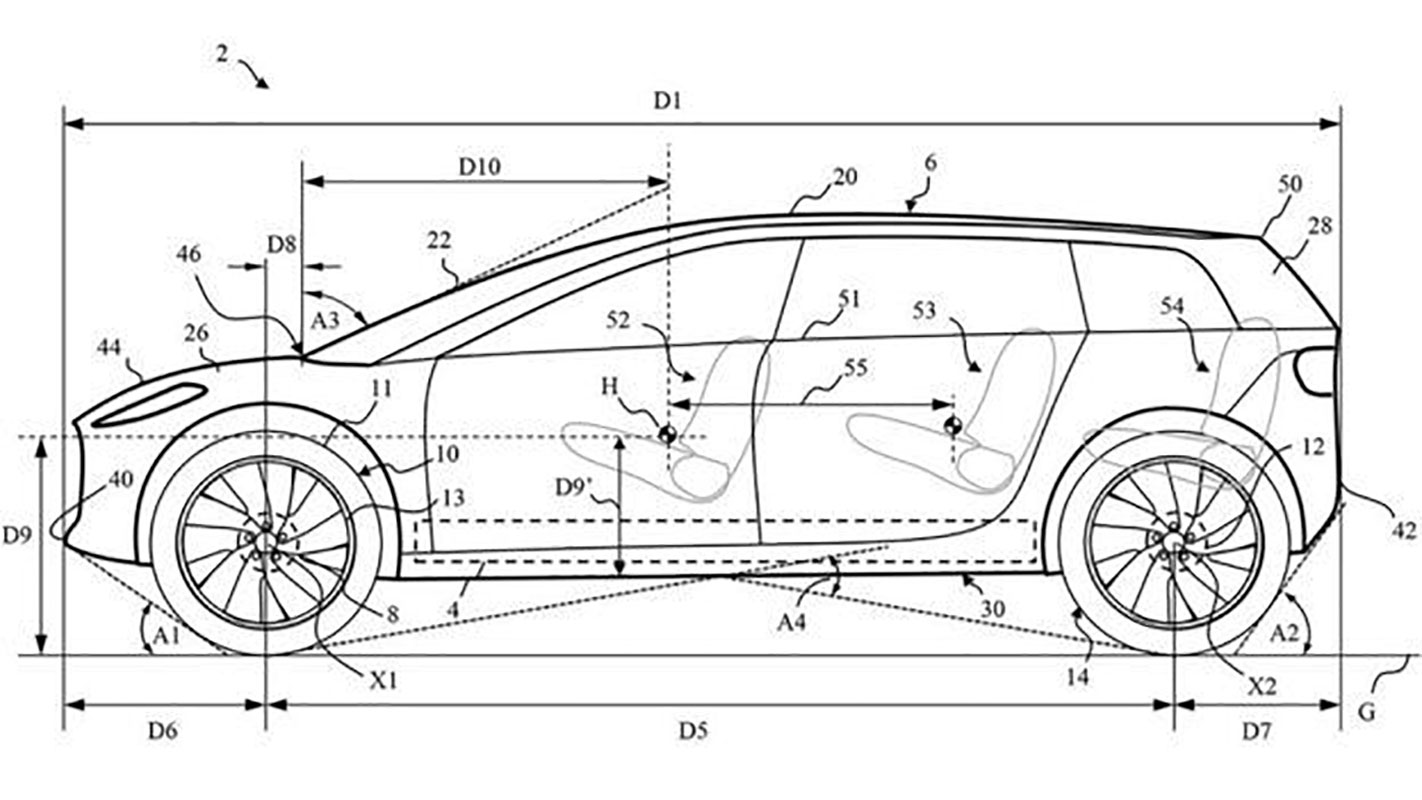

“The Dyson automotive team has developed a fantastic car; they have been ingenious in their approach while remaining faithful to our philosophies.”

He said the firm was trying to find alternative roles for the workers in its home division, which makes things such as vacuum cleaners, fans and hairdryers.

“This is not the first project which has changed direction and it will not be the last,” he claimed.

Dyson is discovering what the likes of Tesla and NIO have experienced in recent years: turning a profit on electric cars is tough. In 2018 note, UBS calculated that the big-selling Tesla Model 3 would remain unprofitable, even with the Long Range battery pack, the company realising a loss of USD $5,900 per car. Few companies have the cash reserves that have been available to Tesla. Dyson is certainly not one of them.

Shares in NIO, a Chinese EV innovator, have slumped by a massive 86 percent from a post-IPO peak last year. Faraday Future, a much-hyped U.S.-based rival, has only just avoided insolvency. Unless it can bring product to market its name will soon be on the list of casualties.

A gargantuan investment into the EV sector from Volkswagen brings the full power of legacy car manufacturers as the Germans go full Emperor Palpatine/fully operational Death Star on fledgling EV startups.

Apple realised that the writing was on the wall for industry outsiders back in 2016. Its well-funded Project Titan hit the skids when the numbers suggested that that its software engineering team would be more gainfully employed developing operating systems for phones, tablets and computers.

Dyson has belatedly realised that it can’t level with the investment Volkswagen and other car manufacturers are making. The company had earmarked $460m for research and development and test track facilities and much of that cash has already been spent. A couple of driveable prototypes exist. Dyson now claims that the Hullavington facility will be repurposed for other projects.

Perhaps it always should have been so. Building an electric car is one thing, building one that’s a viable financial proposition another thing completely. Dyson should have leveraged its expertise in becoming a Tier Two supplier, specialising in battery technology as a partner to major manufacturers. It’s a strategy that has borne fruit for Rimac, whose technology is licensed to many car makers. So keen are manufacturers to access Rimac’s intellectual property that Porsche, Hyundai and Kia have all bought shares in the business.

This should have been Dyson’s path. Hindsight is obviously beneficial, but perhaps the existence of an aircraft that stands as a salutary lesson in not understanding what you are and what you have should have kept Dyson a little more grounded.