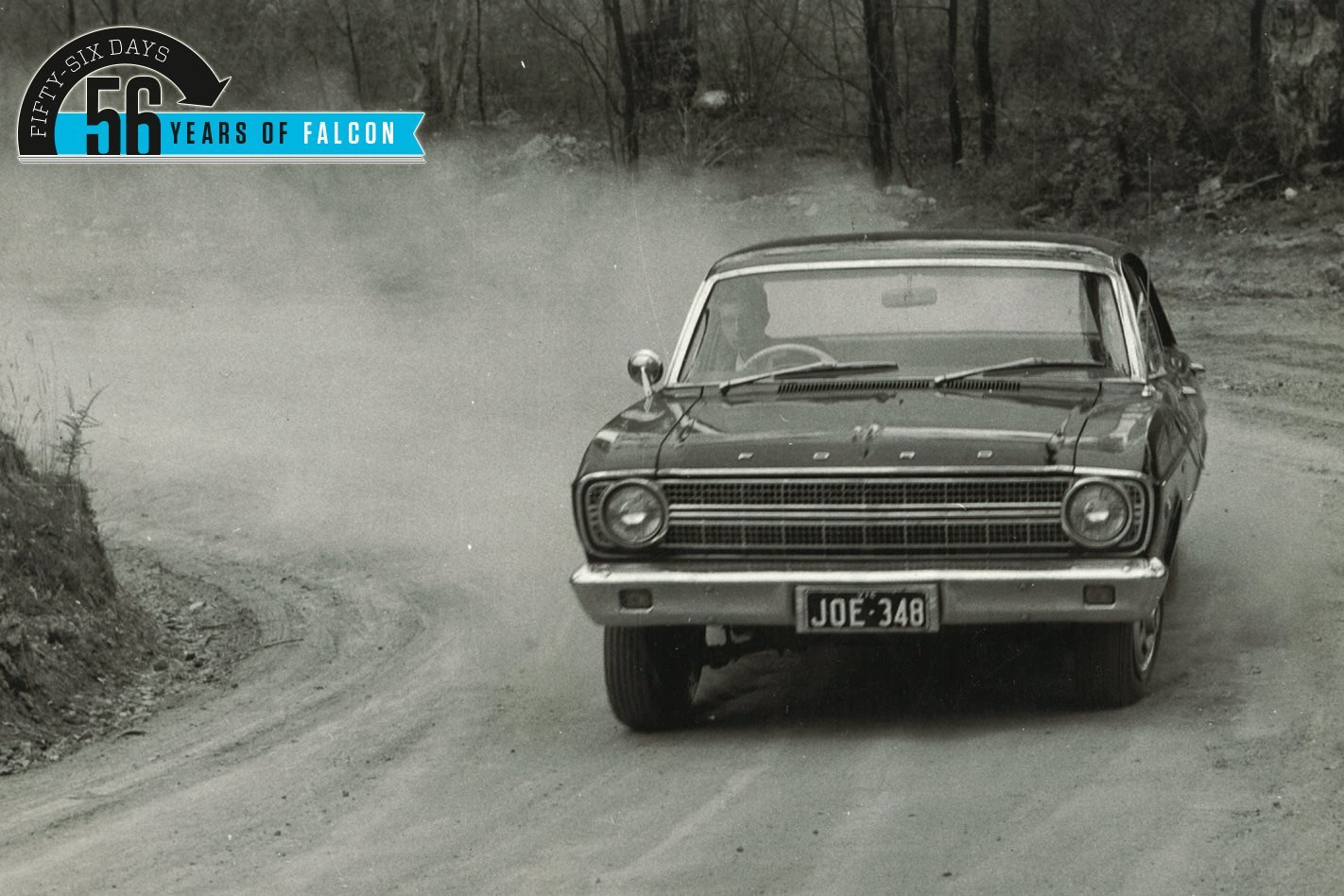

WHEELS magazine has, for the second year running, given its Car Of The Year award to the Ford Falcon.

First published in the January 1967 issue of Wheels magazine, Australia’s best car mag since 1953.

Where last year it was won by the XP series, mainly on the ground of seriously applied development engineering to improve a basically poor (in 1960) product, for 1961 we have given it to what we have described elsewhere as one of the most important new cars to be offered in Australia for years.

The selection this year was the hardest yet. We finally took the unusual step of getting together samples of the three cars remaining in the elimination, the Falcon, the Austin 1800 and the HR Holden and driving them, testing, evaluating and doing everything possible to clear our minds on the matter. We re-assessed the others in the light of this formidable newcomer. The judges decided to make for the first time a special commendation to the two other “finalists”, the Holden and the Austin 1800, for their very high standards.

In a following story we have traced the fascinating path of the car’s conception and development from almost three years ago. But unquestionably the most important thing about the new car is the tremendous influence it will have on the future pattern of Australian car manufacture. We have said repeatedly that the Australian’s taste in cars is drifting steadily towards the use of a V8 in a large car rather than the present “normal” size of compact six-cylinder units, but the XR Falcon is the first evidence of this. It represents a very bold bid by Ford to cater for what it regards as a strong and growing need. It will, in the long run, cost a lot of money, for V8 engine production lines are not cheap to build.

Ford also went out on a limb with an increased range of options. Options represent nothing but headaches to the car maker and heartburn for the dealer, for they are basically against the most important rule in making cars – that the best way to make a consistent profit is to make as few changes to your normal production pattern as you can. Chrysler adheres to this principle with the Valiant and does well. But Ford banked on the projection that Australians are well and truly ready for the advantages to be had in options, and packed everything it could into this new car.

However, these are small things. The most impressive factor in the new car – it’s not quality, for the first production models were decidedly rough — is the engineering. Ford’s advertising, often bombastic, claims the car was built around the V8 engine. We have been right through all their engineering departments both before and after the car’s release, and they are right in every claim they make about the car’s construction.

It would have been very easy simply to pick up the 1966 US Falcon around the end of 1964, make a few alterations to the body, toughen it here and there for Australian conditions, and market it. But, offered this cheap opportunity, they went the long way home. While the styling and mechanicals are basically designed the same as those on the American car, with detail differences, the rest of the car is the result of months of sheer hard work.

In design terms, the Falcon breaks a lot of new ground in the compact field in both suspension, body sub-frames and chassis. Yet with this Ford has given the car an exceptionally quiet ride. It has also demonstrated again, as it did with the XP, its near genius for matching spring and damper rates and balancing out braking effort. On these counts alone the car is outstanding.

A lot of people tend to discount all or any of the three major Australian compacts because they lack the engineering sophistication and dramatic flair of the European car. But it’ is just as hard to perfect a car within the economic limits set by volume sales, the demands of the average Australian driver, and the conditions a car has to withstand as it is to build a sophisticated all-independent sporting sedan. There is no less credit due to these Australian engineers building a conventional compact car for Australia than to his British counterpart working on an interesting four-cylinder small medium car for good roads and small distances. It is a great pity, certainly, that none of the Big Three builds a car like the Renault 16, for example, but their task is to build the car people want — and build it to that formula with all the skill they have.

This is what Ford has done.

The Fourteenth of November

By staff writer Bob Luck

For three years, the XR Falcon was a giant game of chess.

November 14, 1963, was a fairly ordinary day. On that day a RAAF Sabre jet made an emergency landing at Richmond with an engine fire; Sir Robert Menzies had his rowdiest political meeting for years, at Brisbane’s Festival Hall, where he said he would not retire as long as he had his health and vigor; and a 15 ft white pointer shark was killed after it attacked the State Government shark meshing boat off the Queensland Gold Coast. On that day an explosion rocked the US Atomic Energy Commission’s nuclear weapons plant in Texas; it was announced that Australia would reach a population of 11 million two days hence; flags were flown from Britain’s public buildings in honor of the birthday of Prince Charles; and the Namoi Regional Library board announced it had banned James Jones’ “The Thin Red Line”. An ordinary day. A crack was found in the new Commonwealth bridge over the Molonglo River in Canberra; the NSW Premier called for a report on allegations of thuggery and prostitution at Sydney’s Kings Cross; the New York Yacht Club announced the date of trials to pick the 1964 America’s Cup contender; and a new Valiant series was announced.

. . and a folder of documents was stamped with the management seal of approval and changed hands across the board room table In the Ford Motor Company, Melbourne: the Ford Falcon XR was born.

ALMOST three years, millions of dollars and countless ideas later the folder of documents emerged from the production line of the Broadmeadows plant in three-dimensional form. This was September 28, 1966, the day of the Falcon XR. That folder of documents probably covered more distance between various Ford departments in the intervening three years than one of the prototypes that thundered night and day around the You Yangs Provmg ground. That folder probably had more modifications, additions and amendments than any of the experimental mock-up scale models in the styling department. Ultimately, that folder materialised as the most important single contribution to Australia’s motoring progress that the industry has known. It started the era of the low-priced V8 engined family sedan and gave the Australian buyer the most advanced six-seater so far available.

Don’t believe those glib newspaper phrases — the Falcon XR is not just a developed and improved XP. It is an entirely new car. How do we know? We went through Ford’s tightest security doors to find out, to bring you the whole dramatic story of the making of the XR. We were the first journalists ever to be admitted to these areas and were given access to the most urgent secrets in a leading company’s development program. We delved through the closely-guarded files of Ford’s top-security plans and we were ushered into rooms previously forbidden to outsiders, where the Fords of the 1970s are already being formulated. We saw documents, schedules, plans and programs that have never been shown to the press before. Pieced together, they make up the full development story of the Falcon XR – a story of the Australian automobile industry that has never been told before.

We have just said that the XR owes nothing to its predecessor, the Ford Falcon XP, our Car Of The Year last year. But why? A look at the development program provides the answers. The basic design for the XR was approved on November 14, 1963. . At that time the prototypes of the XP had not even taken to the road so it was impossible to improve on an unknown quantity. True, in the latter stages of the XR development some lessons were learned from the behaviour and performance of the XP prototypes and where possible these were incorporated in the new design. But they were only minimal; things like cigar lighter and dipswitch location and type of exhaust system.

The acceptance of the design – on November 14, 1963, for the XR Falcon, was actually just the end of a long chain of developments called “forward planning”. And it was also the beginning of the long chain of events that turned that paperwork into reality. November 14 was crisis day. From that point there could be no turning back.

Before pen is first put to paper on a new model the management meets to decide whether the estimated market situation at the time of the model’s planned release warrants an entirely new model, or just an improved and face-lifted version of the previous year’s car (which is still only in clay model stages at this time, remember).

The Market Research department estimates what the sales volume will be at that time and this is balanced against the findings of the costing departments. The competition department check out the possibility of campaigning the product when it is released. Management examines alternative plans, resulting profit and hands over to engineering to determine how the car will differ from the previous year’s model, that part interchangeability exists, and how many engine/ transmission, body styles and options will be released with the model.

These basic policy decisions were all being made anything up to four years before the model was released, but they still had to go through the approval stage. But before any of this could be approved the whole car had to be presented in package scale drawings for study. These drawings are accurate to plus or minus 0.05 in. and show the place of all the major components.

They detail every aspect of the car’s basic design – factors like ride height, front wheel turn angle and jounce of the wheels, locations of lamps, door opening sizes, interior headroom, angle of windscreen and so on. These are then translated into what are known as “program descriptions”, which nominate the interchangeability of parts, tooling and testing requirements, and overall timing for the project. Engineering presents its findings but all the information is also fed into computers.

Both findings are presented to the top management executive committee on the basis of investment costs weighed against market return. Put simply, this just determines whether the project will or will not make money.

The management committee approved the XR design on November 14, 1963. Immediately every department of the gigantic Ford operation went into action. Each stage is covered by a slightly grey-flannel American phrase or word to describe the process and each of these stages is very clearly defined.

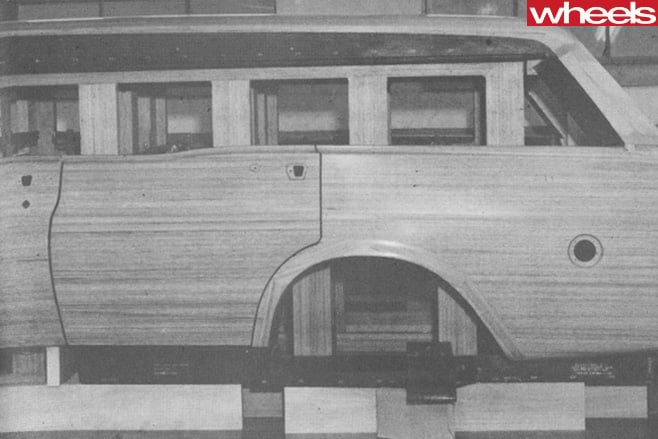

The approved program begins its tour of the Ford Motor Company with a sortie to the Styling Office. This department takes the basic package drawing and proceeds to convert these to complete three dimensional styling drawings-called “renderings”. These renderings fit around the basic requirements of the size, weight and general dimensions of the overall project. They are Styling’s ideas of what the design should look like. At the same time Product Planning examines the designs, measures sheet metal area and other component sizes and begins costing the program. Product Engineering also examines the design very closely to make sure it is entirely workable – there must be proper door clearances, workable amounts of luggage space and so on.

Manufacturing also gets a look in at this stage. They determine whether the panels and components can be formed and placed properly for easy manufacture. Design sensibility is important – it can cost millions to rectify a bad assembly feature on the production line just because proper assembly clearances were not allowed.

On the wagon, Styling Department had raked the tailgate angle far more than the package development drawings allowed; but curved glass was decided on to retain the attractive shape. The clay was approved at this point while fitted with only a dummy grille. The panel work was the all-important factor in styling design at this stage because long-range tooling programs for the sheet metal body work had to be set in operation. Grille design was unimportant and could be decided on later. The clay of the sedan was approved on November 23, 1963 – which is fairly fast work. Less important was the wagon program development and the clay for this was not approved until April 20.

Engineering then compared both package drawing and styling clay models and updated the package drawings to comply with any minimal changes. This department then headed the most important step forward of all-the full design layouts and “design feasibility studies”.

At this point, although complete full-size clay models had been made, the Falcon XR was far from finalised. Engineering then took templates from the clay model and converted these to fine-line layouts, at the same time sectioning each major skin item into parts that could be manufactured and assembled. Each item was examined under the design feasibility studies which determined strength of construction, stress and weight analysis, and position to related parts. All this was either computed or worked out on known engineering principles. The feasibility committee then took each section and examined its potential for easy making, determined exactly how it would be manufactured and assembled (whether spot welded, rivetted or bolted) and what the cost would be. Adjustments were made to the fine-line drawings where necessary and these drawings were eventually made accurate to as fine as 0:30 in. Manufacturing liaises closely with these operations because it will soon have to schedule the spending of vast sums of money in tooling, fabrication of assembly equipment and feeding out components to be supplied by vendors (brake linings, headlights and so on). As each section is approved by all departments and the feasibility committee it is recorded on charts and re-drawn on further fine-line layouts accurate to 0.005 in. This allows for proper door clearances and meeting of metal joints. These final fine-line layouts cover every item of the car – from the body shell to the subframe, mechanical components, shock absorbers, window glass sizes and so on.

These final drawings are traced off to be built up into full-size mahogany templates known as a “cube” or “skin” model. The cube is assembled in sections and each is matched and harmonised perfectly. When the cube is approved by Engineering, Manufacturing, Product Planning and finally the Management Committee, it is broken up and each component sent away to its various sections (or out to component suppliers) for individual tooling.

By the time the sheet metal tooling has progressed to this stage the various mechanical components have been underdoing development. Mechanical prototypes are made up – usually individually – and are tested on machines which test their durability at this preliminary stage.

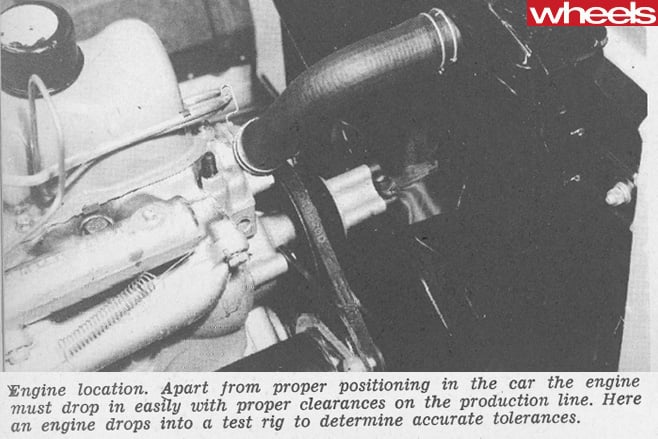

But before these final castings are drawn up the assembled sections of Royalite are examined by the various departments all over again. For example the engine compartment – fully assembled from plastic with the aid of paper clips, no less – is placed on a simulated production line and the engine lowered in to determine proper assembly line clearances. Any fully-assembled section of plastic is known as a “buck” – and this buck must be passed by all departments before its components are broken up and put on the contour cutting, or Keller machine. The XR had a problem with accelerator linkages and the whole linkage had to be re-routed just to allow the engine to drop in easily on the production line, although its mechanical operation was perfect.

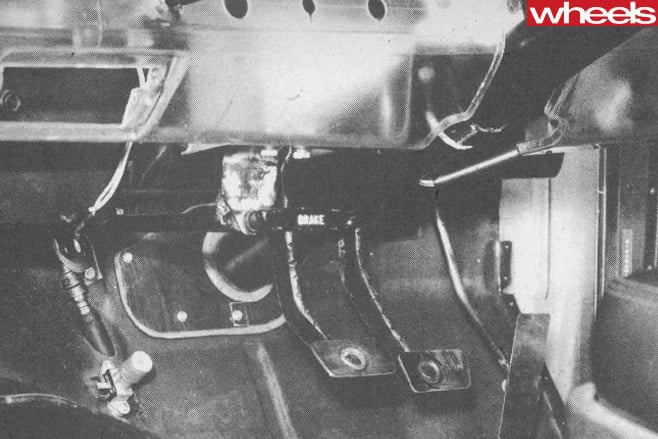

The interior of the XR also brought problems. The whole front floor section was assembled in plastic and the pedals, steering shafts and so on fitted when a special evaluation jury, remembering the XP dipswitch location, determined whether the relative placing of the dipswitch allowed easy use of foot pedals and plenty of foot space. From our viewpoint they made one bad slip in the location of the windscreen washer pedal suspended high up under the dash, but they were aiming for an uncluttered floor.

At this point the whole sheet metal subframe and minor components had been finalised and the various mechanical components had been through their preliminary testing. It was time to make a prototype – the first Falcon XR.

The initial prototypes were completely hand-built. Very early on, fully imported American Falcons converted to right-hand-drive were stripped and fitted with Australian mechanical components for advance testing. But the Australian prototypes rolled onto the proving grounds almost 10 months before release date. They were hand-assembled under simulated production line methods. Each car was programmed for development testing, in a special phase. Like all the world’s leading motor companies, Ford seeks to close up the actual testing time by simulating the life of the car with a much shorter, more rigorous test. There are two types of test: the 40,000 mile endurance test and the 10,000 mile rough roads test. Information from testing procedures of this length are more than adequate to show what the actual vehicle life will be.

Because the Falcon XR was designed around the V8 engine and then fitted with the smaller engines as well, all parts could be interchanged on the prototype vehicles. A typical test program for a vehicle would cover brakes, and suspension performance, a 40,000 mile general test, revert back to specific testing of transmission, vibration, suspension deflection, road shock, handling and so on.

While full prototype testing is well advanced every individual components is subjected to rigorous tests. Windscreen wipers are subjected to exhaustive tests – they must last for three million cycles (all except the blades which must last one million cycles).

Before the final component dimensions are decided the available assembly systems are also examined. Ford has plants in Melbourne and Brisbane with entirely different production lines. The basic design must be adaptable to easy assembly on both lines.

Each outside supplied component (like shock absorbers and electrical equipment) is tested on both rig and prototype cars. With the Falcon XR the most extensive shock absorber testing program in Ford history was initiated. Ford was looking for a special combination of ride and handling with long life and low vibration. Constant modification suggestions were made to the supplier on the grounds of test results.

With prototype testing nearing its end the final development stage was entered – the preparation of construction manuals and the engineering “sign-off point”. A complete manual was prepared for every phase of the assembly of the car, detailing exact methods. These are huge volumes because of the absolute detail they cover but they must give for the production line a simple set of straight-forward stages. There is a manual for body welding, electrical and wiring installations, suspension, engine and gearbox installations, a manual for sealing, trim installation, application of sound deadening material, and a manual covering all tolerallces. A final general specifications manual lists the option combinations in both mechanical and incidental functions from axle ratios to laminated screens.

After prototype testing had been computerised and calculated, and necessary modifications made, the engineers signed off and handed the product over to the time planning committee. Engineering thus accepts responsibility for the final product because there can be no major alterations after this stage. Management again reviews the whole project and a time schedule is worked out from tooling-up to actual press release date. This is based on ability of component suppliers to meet deadlines, availability of raw materials, output of the assembly line, transport and stock required at market release and finally the liquidation program of the previous model.

Even in this program there is room for flexibility, and the XR had three important but not major changes made after the engineers had signed off on the completed approval of the car. Just five months before release a decision was made to change from 13 in. to 14 in. wheels. This was to simplify assembly line procedures because original programming allowed for 14 in. wheels for the VS and 13 in. wheels for the other models. The alteration in no way affected the release date as the suppliers were able to meet the deadlines easily. Most important of all late decisions was the move to put the spare wheel into the fuel tank and under the floor. This went hand in hand with increasing the fuel tank size and the reason for the late decision hinged around later reports from market research and developments by opposition makes in boot space and long range fuel capacity.

At almost the same time the management board decided to widen the seats marginally (about a ins.) to give the interior a more prestigious look.

This is the most amazing part of the whole car’s development program-the extreme flexibility even six months before release date. The alterations are somewhat costly at this stage because of new tests that have to be made and old dies and templates that have to be discarded.

But flexibility is essential too, particularly in fashion which dictates the whole final appearance of the car. To nominate the color of the external paint work and the color schemes of the interior at the original design stages would be hopeless.

The final color schemes are probably chosen only five months before the actual release date of the car. They are basically currently acceptable color schemes with a slightly more modern touch. If deep maroon is becoming a popular color the maroon chosen may be highlighted with metallic tints. In the case of the XR the color choice aimed at sophistication and glamor.

You may well ask if any of this has anything to do with the (albeit littIe-known) postponement date of the public release from August to September. The answer is no. The September release date was determined back in May and was based on the liquidation program of the XP series. At this stage Ford had about 4500 vehicles to sell out before introducing the new model and the crash sales program was started. By balancing out available money, purchasing power of buyers and the poor state of the market, the management estimated late September should see the end of the XP series. As it turned out, the liquidation program was enormously successful and Ford was nearly embarrassed when virtually all units had been sold by the original planned August release date. By that stage it was too late to re-gear the vast public release program so September 28 stayed. Ford is very proud that there was no lay-off period between models as the XP production run finished the XR run was phased in. This saved the four to six weeks staff layoff period that is common in the British and American automotive industry between model changes.

Job No 1 – the first production Falcon – rolled off the lines six weeks before release date, and thereafter XR production began in earnest. By release date there was already a build-up of stock and production was scheduled at a steady rate for the next 12 months.

But with the end of the building story another had started: sales continuity and interim model improvement and development. At the same time as it is solving the problems of various service departments for the immediate present Product Engineering is planning the car of next year, and the year after and the year after that and…

***

ONE of the greatest human failings is to judge a book by its cover; the XR Falcon has been severely maligned because of its wrappings. Too many people who should know a lot better have said that it is simply an Australian modification of the 1966 American Falcon. It’s not. It is· an Australian car, although the sheet metal owes a lot to the original US styling. Mind, Ford is partly to blame in this, for it has extensively used the Mustang image in its promotional work. But you would expect the Press to be more perceptive. The special requirements Ford established for the Australian market are broken into three segments – marketing, environment and economic production.

Here are the main points of difference between the Australian and American car – first in terms of marketing requirement:

- Different sub-frame structure due to increased areas of rear seat passenger space.

- Larger capacity fuel tank, different spare wheel location.

- Higher, 4 in. wider front seat, better visibility. Different seat spring rates.

- Interior bonnet lock.

- Locking vent window handle combined with altered body character lines. Wagon has most differences.

- Different grille and ornamentation.

- Australian-conceived trim design and color schemes.

- Significantly different wagon styling with much bigger internal space and better seat folding system.

- Much stiffer suspension with altered ride characteristics.

- More responsive steering (ratio is 20:1, American 22:1).

- Different basic vehicle structure. Extra reinforcing comes from heavier gauge upper engine compartment members, floor side inner and outer members, rear side members, rear shock absorber mountings and reinforcements, rear floor side panels, rear cross members and fuel tank.

- Reinforced suspension housing and front suspension bumper brackets.

- Overlapping of joints of front torque boxes, front fenders, and engine front members to relieve high stress areas.

- Welded flanges, Increased gauges, and added reinforcements make up the engine compartment structure with the dash-cowl areas for better rigidity.

- Wagon structure is developed to Include tailgate opening pillars and increased overlap of pillars to roof rails and robust rear spring mountings.

- Large departure angle of wagon to allow for rough terrain.

- Skid plate added to all 289-engined cars for sump protection.

- Redesigned rear lamps.

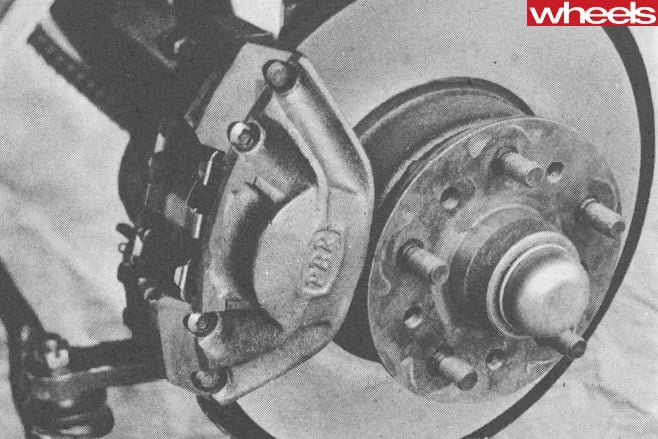

Window winders, headlamp housings (required revisions to front fender sheet metal) toughened windscreen glass, windscreen wiper motor and washer pump (revisions to linkages and body mountings), bumper jack, seat belts (special structural adjustments) carburettor (environmental calibration), starter motor; shock absorbers, wheels and tyres, rear axles (mounting and clearance revisions), drum brakes, and wheel cylinders, disc brakes and callipers, master cylinder, lining materials (all requiring adaption of vehicle structure), automatic and manual transmissions (special mountings, shift linkages affecting body structure, exhaust system, brake lines and steering column), clutch and master cylinder different hydraulic operation and moulding), exhaust (special hangers and altered structure), local heater, demisting and air conditioning plants, instrument cluster and controls, gauges, radio, battery location, alternator and regulator.

The Ford Australian economic structure also called for far greater component interchangeability. These were some of the points that were common:

Common foot floor pan, rear torque boxes, rear shock absorber member and reinforcements, wheelhouse inner and outer, front doors, centre pillar, engine rear mounts, rear lamps, rear axles, exhaust system and drive shaft.

Check out Wheels Archive online now for other great Ford Falcon features and more from decades past!

Simply log in here using your existing MagShop account or create a FREE account and select this article from the homepage.

Don’t have a MagShop account?

Have a MagShop account?