Grand Prix – the words conjure images of open-cockpit cars with barely restrained power, their engines screaming to the heavens and assaulting your eardrums with a cacophony of noise. Except we’re at a Formula E grand prix, where the loudest noise is the staccato hammer of the pit crews’ air wrenches.

We’re in Long Beach, California, for the Faraday Future ePrix. Where Formula 1 fans are used to a haze of high-octane fuel and hot motor oil hanging over the track, here it smells of roasted almonds, burgers and fries, and the sea. Fans chat freely as the cars race by, the whine of electric motors occasionally overpowered by the screech of brakes as tyres bite into the concrete. It’s a curious sound, usually drowned out by the roar of braking petrol engines.

With a 28kWh Rechargeable Energy Storage System (RESS) supplying a capped maximum of 170kW (lifted to 200kW for qualifying) and 230Nm to the drivetrain, these peculiar electrical creations will do 0-100km/h in just under three seconds, and go on to a top speed of 217km/h. They’re constructed of ultra-light carbon fibre and aluminium, to a minimum weight limit of 888kg.

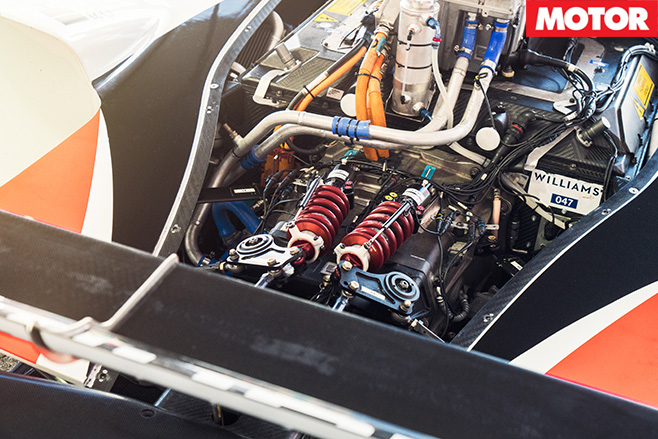

In its first season, the teams were all supplied with Spark-Renault SRT 01E racing steeds – chassis by Dallara, McLaren motor, Williams Advanced Engineering battery system, Hewland five-speed gearbox and Michelin tyres. Now in its third season, it’s still a fairly standard design but teams are able to install powertrains from different manufacturers. However, given the still rapidly evolving technology, little things make a big difference – it often comes down to small details like suspension adjustment according to Aguri team principal Mark Preston.

With the restrictions on cars being loosened, teams and manufacturers are now free to apply their own innovations to their machines; for example, anything from one to five gears in a ‘box with a housing made of cast iron, aluminium or carbon fibre.

Just as with F1 pitstops, moments gained or lost during this mad race to swap cars is often the decider in whether someone ascends to the top of the podium or watches the champagne spraying from below.

However, while pit mishaps have added a thrill of suspense to the races, the mandatory stop will be dropped when the next-gen 250kW motors appear in 2018, meaning drivers can go for longer without changing cars.

But what really makes this format special is the level of interaction between fans and drivers the organisation encourages. Rather than spending hundreds of dollars on a bewildering variety of access tickets like F1, Formula E charges roughly $100 for a family ticket that grants access to the eVillage (Parc Ferme) where drivers gather for autograph sessions with fans, as well as a seat in the grandstands flanked by video screens and access to a new interactive world of motorsport that targets the smartphone generation.

Formula E is all about encouraging and engaging new talent and ideas. Formula E founder Alejandro Agag is all for the burgeoning market of innovative young thinkers. “In the next five years, technology is going to explode,” he says. “I’m not only talking chassis, batteries, motors and electronics here. Global digitalisation is the next revolution. Millions of young people will follow Formula E by pairing their competitive mindsets with the new digital opportunities. Today, we have 20,000 users per day, 15,000 more than in 2014. Next year or the year after, we may have five million.”

Hans-Jurgen Abt, whose drivers finished first and third in Long Beach, views this race series as “a significant bridge to volume production”. Why? “Because it is way ahead of traditional car development in terms of cooling technology, software expertise, performance electronics, vehicle integration and battery management.

At the same time, Formula E is casting a spell over a young, fast-growing and well-funded web-focused audience. The new business opportunities which materialise in the wake of Apple, Tesla and Formula E should be reason enough for every major automotive manufacturer to secure a seat in this event.”

“From a commercial point of view, one of the key attractions of Formula E is the budget restriction,” says commercial director of Dragon Racing Kevin Smouth. “While an F1 team has up to 150 people on its payroll and spends up to $100m per season, we have between 10 and 15 staffers and a kitty that holds no more than $6m. The most expensive spare part in Formula E is the battery. It costs close to US$100,000 to replace, but it rarely goes haywire.”

The cars are set up on Thursday, with ride height, spring rate and tyre pressures all being calibrated. Testing occurs on Friday, often resulting in precise adjustments being made in preparation for the main feature at 4pm on Saturday afternoon. By Sunday the vehicles have been loaded back onto the team trucks and council workers are restoring the surrounding city streets back to normal in preparation for the Monday rush, almost as though it never even happened.

Weight is of the essence, though equally the right strategy is essential. “Ideally, you get off to a good start, then conserve energy and try to keep the rivals at bay,” Piquet says. When all go-faster options have expired, the last hope is FanBoost, a live online vote that rewards the three most popular drivers with an over-the-air power boost not unlike the push-to-pass effect we know from F1, potentially changing the result in a blink of an eye and a tap of a finger on a touchpad.

Official safety driver Bruno Correia slips into his BMW i8 pace car, tightens his safety harness and goes through his usual pre-race routine. Radio? Check. State of charge? Check. Flashing lights? Check. Correia has no choice but to go 10-tenths as soon as he enters the circuit. “That is not a problem during the out lap, when I lead the field to the grid,” he explains, “but in case of an accident, I can only go really fast for six or seven laps before the batteries die on me.”

Excitement is an understatement as the pack races around a circuit filled with nail-biting crowded chicanes that force proverbial-tightening overtakes. Like F1, fastest laps always occur at the end of the race – not because of light fuel loads but because as the chequered flag approaches, everyone gives up on economy and squeezes the last kilowatt-minutes out of the battery packs.

Unique to plug-in racing is the energy reserve display shown alongside the timing in the steering wheel. It’s important as two or three per cent more juice can make a big difference, either as a power boost for a late attack or to squeeze in that additional lap before the change-over.

Naturally, with the cutting-edge nature of the still-evolving technology, there is plenty that can go wrong. If there’s a problem with the high-voltage electrical system, the green light in front of the driver turns red, prompting everyone to take extra care before even touching the car. And there is some old-time technology still finding a use in this world – as cars enter the pits, marshals blow whistles to warn the mechanics – a simple solution to the low-noise danger of electric cars in the modern world.

The race was run and done before we had a chance to open our second beer, Swiss driver Sebastien Buemi taking the chequered flag for Renault e.dams.

No ludicrous fees for tiered entry, no closed-off areas reserved for stars and high society, just the fans, the drivers and the passion for the sport. As the field opens up to more teams and more technology, social media and the prospect of increasing levels of user-driven input like the current FanBoost drawcard driven by anyone with an idea and a smartphone, the future looks bright for this emission-free spark.