THIS might upset some people and could, quite rightly perhaps, see my ‘Aussie card’ revoked, yet I have reached the unshakable conclusion that in the bitter rivalry of Australia vs New Zealand, the land of the long flat vowel currently has us beat.

Rugby union fans will need no reminding of this soul-crushing power shift, yet even accounting for the fact that Kiwis are nicer, more relaxed, are the true creators of pavlova, the egg beater, Russell Crowe, and can, apparently, lay claim to inventing the humble pair of thongs (who knew we should have been calling them Jandals all along?), they also seem to have us licked in another area: automotive ingenuity.

Motorcycle fans will already be familiar with the likes of Burt Munro and John Britten, and now there’s a new, cutting-edge auto start-up that makes anything being built in Australia right now seem prehistoric.

The company is called Rodin – don’t worry, I hadn’t heard of it either – and its immediate mission is as simple as it is ambitious: to build the world’s fastest and most exciting track car.

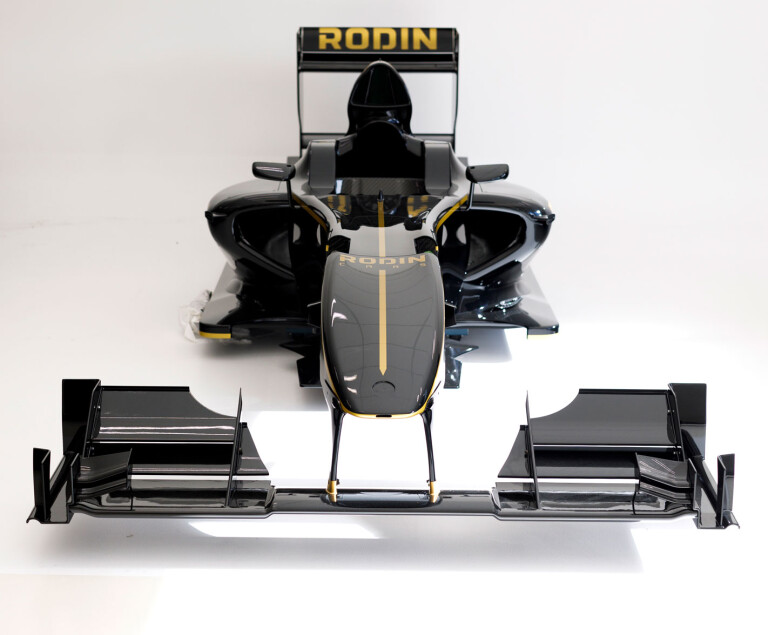

The result is, to the untrained eye, a Formula One car. Resplendent in black with an exposed carbonfibre finish and gold detailing, the brooding behemoth – dubbed the Rodin FZed – has all of the calling cues to make Daniel Ricciardo feel right at home: enormous wings, oversized slick tyres, shrink-wrapped bodywork and a removable steering wheel festooned with dials and buttons.

It’s the closest thing to a Formula One car that money can buy (we’re driving it next month, so stay tuned), but what really boggles the mind is that the FZed isn’t the fastest car Rodin is building. That creation, which looks like a fighter jet canopy with wheels and is powered by Rodin’s own V10, is called the FZero.

“But hang on!” I can hear you posturing, “Australia has the Brabham BT62, which is capable of lapping Mount Panorama faster than any tin-top racer before it!”

Well, dear reader, in the game of top trumps, the FZero’s claim is that it will be “quicker than a current Formula One car”.

Rodin’s aim, then, is to exist on another level altogether. One that doesn’t only make it the equivalent of established players like Pagani, Koenigsegg and even Ferrari and McLaren, but should see it rival hypercars like the Aston Martin Valkyrie and Mercedes-AMG One. Sound a little unrealistic for a start-up from New Zealand? I thought so too, until I visited Rodin’s facility and met the company’s creator.

David Dicker fits the description of a millionaire recluse almost perfectly. Tall, bespectacled and in his mid-60s, Dicker’s defining features are his flowing white hair, his quiet, thoughtful demeanour, and a razor-sharp mind. He’s a self-made man, having built his fortune the hard way by creating an IT business, Dicker Data, from scratch.

“I never went to university, but I think if I sat the computer science exam I’d have been able to pass it because I had all the same textbooks,” says Dicker. “But yeah, I’m basically self-taught.”

Dicker’s business success is well documented. Last year Dicker Data turned over $1 billion and had 400 employees, which, you might think, would be enough for most people. But in 2004, Dicker decided to turn his hand to a new passion project. Rodin Cars is the result. “I’ve always liked cars and I’ve always wanted to build my own,” Dicker says. “I had a kit car when I was a kid, a Bolwell MK7. I enjoyed the engineering and design side as well as the driving.”

Offering some consolation to us Aussies is that Dicker was actually born in Sydney, but he chose New Zealand as the base for Rodin because “Australia is killing the car”.

“The car culture in Australia has just been destroyed by the government,” Dicker says, shaking his head sadly. “I’ve read Wheels since the ’70s and probably drove the Bolwell too quickly, but you used to be able to. Now the police are just so aggressive. Here in NZ it’s very different. It’s like it used to be.”

My Rodin initiation starts with a tour of the primary pit complex, nestled on a ridge overlooking Dicker’s 570-hectare property, two hours north of Christchurch. The central building backs onto a multi-car pit bay currently filled by three racing cars – a McLaren 570S GT4, a Formula 3 racer, and the FZed. Buy an FZed, for the princely sum of US$615,000 (A$866,000) before delivery charges and taxes, and you’ll get to drive all three. It’s part of the ownership experience, which also includes one-on-one coaching from Rodin’s chief driving instructor, Mark Williamson, and the chance to stay in one of the yet-to-be-built luxury villas that will overlook the circuits.

Ah yes, the circuits. Plural. Ringed as it is by snow-capped mountains, Rodin’s facility meanders across undulating terrain and includes three tracks.

‘Stage one’ was built first and is like a glorified go-kart circuit. ‘Stage two’ is much more serious: a 2.4km ribbon of tarmac with enormous elevation changes, blind crests and vindictive turns.

“It’s hair-raising,” says Dicker. “It’s intimidating, actually, that’s why I don’t drive it much. I’ve spun in every corner.”

‘Stage 3’ will be the domain of most Rodin owners. A flat piece of tarmac with seven turns and a 900m straight, it’s deceptively challenging and fast. “You’ll hit 260km/h in the FZed,” says Dicker.

He’d know, too, given he designed the tracks. This desire to create everything from scratch is a recurring theme for Dicker. Throughout his career he’s built his own supercomputers, written code, and designed and constructed his own sails for superyachts.

“It’s actually a real problem,” says Dicker of his need to begin with a clean sheet. “When I was young I didn’t want to do a project unless it was so difficult it was almost impossible.”

Demonstrating just how committed Dicker is to the whole DIY thing is the fact that instead of hiring contractors to build his tracks, he bought the excavators and bulldozers.

“It took longer but the end result is better,” he says sheepishly.

This desire to be the master of his own destiny is perhaps at its most fastidious in the three manufacturing sheds.

Here, Rodin’s 12 staff members design, create and test the components required to build their cars at a level that’d please most Formula One teams. This includes everything from wiring looms to composites and 3D-printed titanium parts.

“You need to make your own stuff,” says Dicker. “At the production level it’s not so much of a big deal, you can use contractors, but when you’re doing R&D, you’re just totally screwed if you can’t make your own stuff.”

I’m handed a Rodin bolt, 3D printed from titanium and finished with a unique gold coating. Then I’m given another, the same length but silver and heavier, and with a coarse finish.

“That’s a Ferrari bolt,” says Dicker. “If you look at the Ferraris and the McLarens, they’re pretty awful really. They’re agricultural. I like Ferrari; don’t get me wrong, but the hardware is … you know … not great. It’s low-end, let’s put it that way.”

I was expecting Rodin to be something of a ‘man and a shed’ project. The reality, however, is that it’s more like a mini McLaren Technology Centre. The scale, ambition and attention to detail is astonishing. So too is the investment.

Dicker says he’s given up counting how much he’s spent at Rodin, but he does admit the last number his accountant shared “some years ago” was $17 million.

“And that’s chickenfeed to what the big guys spend,” Dicker says.

Incredibly, despite having no formal training or an engineering degree, Dicker designs every component himself using CAD, from bolts and brackets to carbonfibre wheels with 3D-printed titanium centres.

Lurking under a sheet in the final manufacturing shed is an early prototype of the FZero, complete with a full-scale plastic model of its V10 and an empty space for the eight-speed gearbox housing, both of which are being made to Dicker’s design. This, more than anything at Rodin, has me perplexed. Why build your own V10? Even Pagani and Koenigsegg don’t bother, or simply recognise the expense is too great. Dicker’s answer is simple.

“From a marketing standpoint, if you have your own engine, you’ve put yourself in a certain position. If you build a car with a crate motor or an engine you buy from someone else, you put yourself in a lower position. Look at the Brabham. The Brabham guys are going to be screwed because it’s a Mustang crate motor.”

Spend too long at Rodin and it’s easy to suspend reality for a moment as you marvel at the craftsmanship and the sheer scale of the ambition, yet at some point reality needs to creep back in. That moment arrives when Dicker reveals how many cars Rodin is expecting to sell.

“If I could make a deal right now to sell 50 cars a year, I’d take it,” he says. “If everything was working we might think about building 100 cars a year but that’d be the absolute maximum.”

Slightly cynical, I ask Dicker if he’s run the business case on whether there are actually 50 people out there willing to buy a car like this.

“Well, no, not really,” is the reply. “There’s nothing like the FZed available, so we’re building that market from scratch. Obviously that’s risky, because most people would say there’s no market. But if you want to be successful, you have to be the market leader in whatever category you’re in. That’s our opportunity.”

Sceptics will no doubt scoff, and it’s true that outside of the Rodin bubble, some of it sounds fantastical. Yet as I’m strapped into the FZed and I flinch as the big Cosworth V8 fires, the entire car erupting into a cacophony of noise and vibration as I try the throttle for the first time, it’s difficult to muster much doubt that Rodin will make it work some way or another. After all, New Zealand has form at taking on the big boys. And winning.

COMMENTS