THE ONLY person I can see is wrestling with a reel of fencing wire, the wind attempting to tear his clothes from his back. The mercury’s hovering just somewhere north of zero and the wind’s ripping in off the Bass Strait. Grey sheets of rain queue up offshore, ready to begin their strafing runs. I look over to the farmer and he’s grinning from ear to ear. I crack the window of the Camaro ZL1 down a few centimetres. “Go on,” he yells, dropping the reel and rolling his fist in the universally acknowledged language of petrolheads everywhere, “punch it!”

Australia loves a good V8 and it’s easy to understand why. A bent-eight speaks of qualities many of us identify with; a rugged toughness, dependability, heritage, performance over parsimony and an irrepressibly larrikin ability to paint a smile on your face. We’ve gathered six of the very best of the current crop of V8s for a celebration of the engine, and we could easily have brought more, but we had to draw a line somewhere.

Chevrolet’s 477kW Camaro ZL1 by HSV ($162,100) is the catalyst for the great Gippsland gruntfest, but it isn’t even the most powerful vehicle here. That honour goes to the 522kW Jeep Grand Cherokee Trackhawk. Taking a radically divergent approach to the generation of its power-to-weight number is McLaren’s fierce and focused 600LT Spider. Pitch in a couple of 5.0-litre atmo heroes of very different persuasions – the Ford Mustang GT and the Lexus RC F – and then round out the gathering with the Mercedes-AMG C63 S.

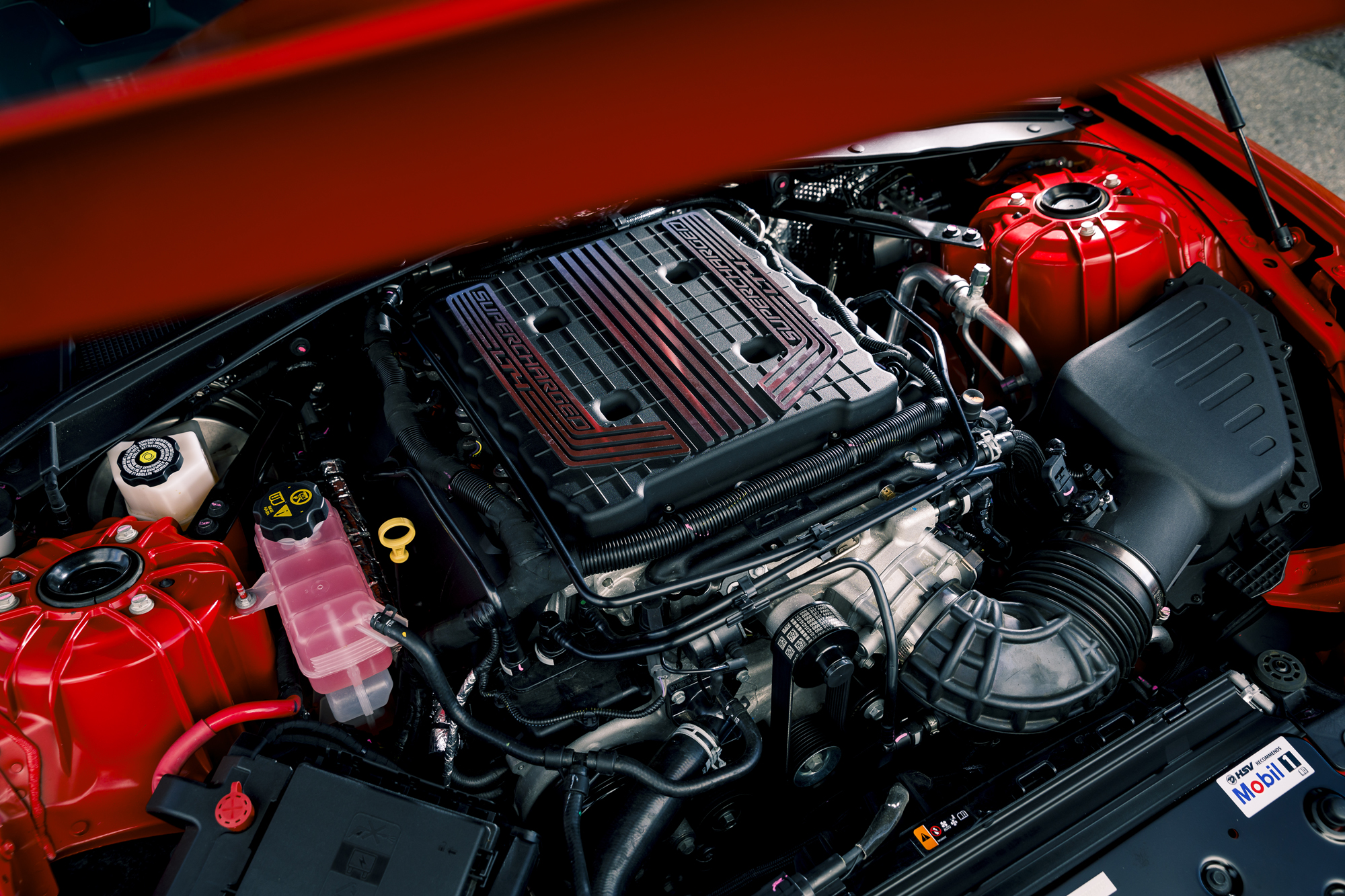

The Camaro disappears up the road in a cacophony of 6.2-litre supercharged small-block and tortured treadblocks. I’m laughing, the farmer’s standing in the road behind, also cackling with pure joy. The ZL1 is that sort of car, up to a point. With 477kW and 881Nm under your clog, it’s clearly something that demands respect. The engine is a keening, bellowing block of drill-sergeant aggression anywhere from 3000 to 6500rpm.

Our test car is the 10-speed auto that most Aussies will choose, but the manual car might just be the pick. With a stubby, ‘sueded microfibre’-clad lever, a real satisfying eight-ball break of a shift action and the most delightful rev-match function, it’s the perfect accompaniment for the tactility of the ZL1.

While the LT4 lump lacks the exotic materials and bespoke competition feel of the LS9 that powered the GTSR W1, it is objectively a better engine. With direct injection, dual-rate oil pump, cylinder-cut technology, better cooling and more effective breathing, not to mention a supercharger and intercooler that’s 9kg lighter than the LS9’s atop the motor, it feels even more blue-collar tough. The small-block has been around since 1955 and while a lot has clearly changed, it’s an engine that can still trace a clear bloodline: eight cylinders, 90-degree vee formation, single-cam pushrod valvetrain, and 4.4-inch bore spacing.

The power curve for the LT4 isn’t a curve as such. It’s just a constantly ascending line, the engine making peak power at 6400rpm, and even then it’s not really plateauing. That 881Nm of torque appears at 3600rpm, which means that the LT4 does like a few revs on the board. Not a lot happens below 2800rpm, but then the note firms and from 4000rpm you feel like you’re just hanging on for the ride. The manic, giddy surge from there to 6000rpm is never the same twice, largely due to the inadequacy of rear traction. This isn’t entirely HSV’s fault. The ZL1 was engineered for the super-sticky Goodyear Eagle F1 but these tyres couldn’t pass the ADR split-mu test without a revision to the car’s ECU. Clayton wasn’t permitted to start editing the ECU software so has instead resorted to fitting Continental ContiSport Contact 5Ps which do pass the test, and offering the Eagles as a $1000 ‘track tyre’ option. While the Contis work brilliantly on a four-cylinder Commodore, they’re not an ultra-high-performance tyre, so do compromise the ZL1’s ability to put down its power. Our acceleration tests show that the ZL1 on Contis is around half a second slower to 100km/h than a cooking $86K Camaro 2SS on Eagle F1s. In other words, you need to tack on a grand to get your Camaro back onto the more hardcore rubber.

Tiptoe up through three gears and plant it in fourth and the ZL1 will rapidly disabuse you of any notion that modern production cars are uniformly sanitised and make going fast feel effortless. Three figures on the clock, five degrees of yaw apparent with all the driver aids switched on and the Gen V small-block sounding as if it’s about to fire its Eaton 1.7-litre supercharger into low earth orbit will always grab your attention. The thin-rimmed steering wheel wriggles and bucks, and you wonder when the maelstrom will subside. As good as the ZL1’s body control is, it’s often more sympathetic to tap out with a couple of rapid upshifts than lift off the gas.

The ZL1’s engine dominates proceedings given the grip levels available, but the rest of the package – tyre excepted – also benefits from a massive development budget. It’s hard today to reconcile the Camaro’s tenuous grasp of the bitumen with a sub-7m30s lap of the Nordschleife, but that’s what this car is capable of, and some of the detailed calibration speaks of a rare attention to detail. The Magnetic Ride Control adaptive damping offers a polished edge at odds with the aggressive image, while the throttle calibration and brake modulation is top-drawer stuff. The steering offers a lot of heft in Sport and Race modes but some testers felt that weight was arriving without a concomitant improvement in feel.

I’m left slightly bemused by the Camaro. There’s a fierce car in here but conditions and tyres are against it today. There’s certainly a great V8 under the bonnet, but is it the best V8 here? Is it even the best 6.2-litre supercharged V8? To answer that question, enter the heaviest hitter of the lot.

Westerman: Trackhawk swaggers in with the highest outputs of the group, but here’s the question: is stuffing what is essentially the engine from the 11.2-second quarter-mile Dodge Challenger Hellcat into a 2.4-tonne SUV an act of genius, or a moment of madness? All depends on your priorities and point of view. The 522kW/868Nm Trackhawk ($134,900) demands that you take ‘logic’ and file it in your dark recesses; that place where some of us park notions of ‘plausible religion’ and ‘slimming beer’.

Jeep’s flagship is irrational, excessive and unnecessary, but also, I’d contend, mostly lovable. The distant sound of blower whine is present from the moment you pull out from the kerb, but otherwise the low-speed powertrain manners are docile; the throttle tip-in relaxed yet precise. Helpfully, every individual parameter can be set to your preference of Street, Sport or Track.

With everything set to ballistic, and launch control engaged, it bolts off the line like a rhino with an IED jammed up its clacker. The combination of bulk torque and monster traction mostly overcomes the huge weight to send it hurtling to 100km/h in just 3.7sec. On the move, only slightly dull-witted downshifts blunt the instantaneousness of its ferocity; take charge with the paddles and hang the hell on.

“From the outside, it sounds like a piston-engined bomber on approach,” says Kirby. Inwood was no denier of the epic engine performance, but a bit harder to convince as to Trackhawk’s broader merits: “A bit of a one-trick pony,” he says. “Even in track mode, the steering’s too remote and it just doesn’t have real handling cohesion.”

Okay, but what was unanimous was just how well-engineered and utterly bulletproof the driveline feels. And who, of the target market, is really going to take their Trackhawk to a trackway, or try and stay on the bumper of a Cayenne Turbo through their favourite twisty bits? No, the Trackhawk finds its following among those who’d really love to buy the Camaro, but need an SUV to cart kids and bikes and the chattels of family life. Think of it as a high-riding, family-friendly, blown muscle wagon; one that comes loaded with a level of standard kit for which the Euros would demand a kidney. Actually, just don’t think too hard about anything and the more persuasive the Jeep flagship becomes.

Jumping from the least dynamically adroit car here and into the most – the McLaren – is like stepping out of a bubbling jacuzzi and into a bobsled. The 600LT Spider ($496,000) runs the British company’s 3.8-litre version of its ubiquitous twin-turbo V8 in the highest output available: 441kW and 620Nm, which is a bump of 22kW and 20Nm over the 570S model below. The gains come from a change of cams and an ECU tweak, among other things, but in this installation, it’s the short-route, top-mount exhausts that arguably have more impact – viscerally and audibly – than the actual power gain. Some of us (okay, me) initially wondered if the engine as a drawcard may have been shaded by the chassis gains, given how focused this car is. It’s stripped of weight, runs suspension components lifted from the 720S (from the series above), has carbon-ceramic brakes and Pirelli Trofeo R tyres, so clearly not built to just ponce around in a tight T-shirt outside nightclubs. But despite all that, it’s still the engine that will – initially at least – blow your mind.

The motorsport roots (see sidebar, right) remain infused throughout, especially in the sound it makes during normal, law-abiding driving. It’s a nondescript, industrial-blender type of sound, like something in Soup Nazi’s kitchen, and devoid of that V8 burble that you may expect. Only once you start opening it up can the V8 start to really communicate with you, via induction snarl, turbo whistle and wastage chuffing. But push through that, keep it held wide open, and lord, prepare to be transported to somewhere special, both literally and figuratively. Don’t call it laggy, just be mindful that when full boost is pumping at around 5000rpm (peak torque is super high for a turbo at 5500-6500rpm), things are about to get properly feral. The Spider allows your ears unrestricted access to those exhausts just a metre or so behind your head, and the sheer sonic hatred they spew forth is breathtaking. In the wet, as much of our testing was, this engine just tries to tear the treads off while sending the ESC into apoplexy as the overworked electronics try to deal with the onslaught. It’s a startling, sensational mix of boosty turbo torque married with an almost atmo-style appetite for revs – cut-out is at 8500rpm – and culminates in a barrage of frenzied mechanical meshing and subsequent sensory overload that makes the 600LT part of a very elite breed. Fact: if you drive this car, and think, “Hmmm, wish it was quicker; I should have gone for the 4.0-litre in the 720S”, see a specialist, you have a serious disorder.

Inwood: We’re deep into day one of our celebration of bent-eight brilliance, each driver cycling through the six cars to better understand the magic of V8s. It’s quite a thing to watch them roar away from our roadside base. The Trackhawk is brutal, its rear axle squatting like a powerlifter before it launches, the sheer scale and force of the thing seeming to punch a hole in the laws of physics. The manual Mustang is less manic, its deep burble broken into musical bursts as the driver pauses to shift gears. The McLaren, however, is unhinged. Having set off fizzing with childish glee, the expression of a returning McLaren driver is a kind of stunned stupefaction. They emerge looking as though they’re in need of a nice lie-down, which invariably sees them drawn to the Lexus.

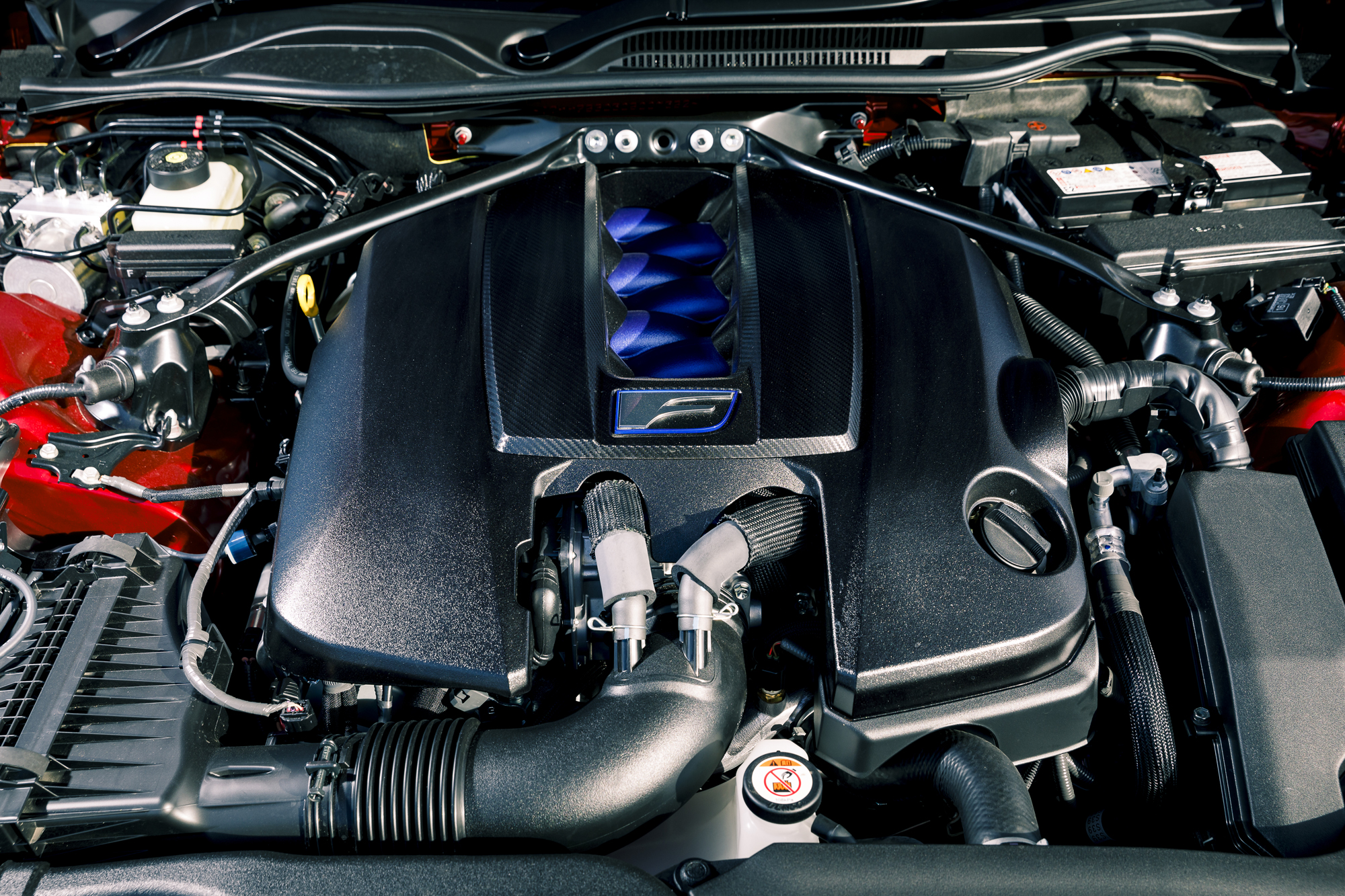

It’s odd to describe a car with a 351kW/530Nm 5.0-litre V8 as gentle, but in this company, the RC F ($137,729) is something of a soothing balm. Where the others flex their V8-ness with lumpy idles and ferocious potency low in the rev range, the Lexus favours subtlety. In fact, fire it up and you might be duped into thinking it’s powered by a V6 or even a turbo four.

“Its personality is so opaque,” quips Enright. “If you didn’t drive it hard, you might never know that it’s actually a V8. But it’s so turbine- smooth and polished, it’s actually quite lovely.”

The general agreement is that while the other cars might be more exciting, the Lexus is the one we’d all want to spend long periods of time in. Exquisitely crafted leather seats and a comfortable, well-judged ride have a lot to do with that. There’s a duality of character at play here, however. Twist the drive select dial from Normal to Sport S+ and the RC F responds as though it’s copped an EpiPen to the heart. Revs are at the core of the excitement. After the forced-induction savagery of the McLaren, the RC F’s bottom end can feel light on, but temper your need for instant gratification and the atmo V8 rewards in a way no turbo donk can. Nothing else here builds with such musicality or changes timbre so beautifully, and only the Mustang comes close for linearity of power delivery. The boffins inside Lexus’s F department don’t believe in turbos and today, on soaked roads that demand an intuitive understanding of grip and slip, I’m kind of grateful for that.

In fact, where the Continental-shod ZL1 looks a handful, the McLaren verges on being too focused and the Trackhawk is ponderous, the RC F feels almost ideal for these conditions.

You get a similar sense from inside the AMG. Technically the C63 S ($160,900) is a rival for the Lexus (we were hoping to drive the facelifted C63 coupe, but just missed its arrival in Oz), and like the RC F there’s something right-sized and confidence-inspiring about a C63 on a winding Aussie B-road.

Unlike the Lexus, however, the AMG thrills in a vastly different, and significantly more visceral, way. Where the RC F is all about cultured refinement and delayed satisfaction, the AMG is instantly more aggressive. The 4.0-litre mill fires with a bark and the entire car trembles with an off-beat motion as the big brute settles into idle at 700rpm. It sounds wet, as though enormous fuel lines are dousing the combustion chambers with 98RON, and it’s the only car here with an active exhaust button. With the pipes open few cars sound this sinister, even sitting still.

Because it’s been with us since 2014, it’s easy to forget just how sophisticated AMG’s V8 actually is. Debuted in the pre-facelifted C63, much was made of its ‘hot vee’ design which brought packaging and performance benefits, but the heavy use of aluminium and exotic materials such as zirconium also mean it’s impressively light at 209kg dry. It’s also available in subtly different guises. In the C63, the BorgWarner turbos are single-scroll units, but step up to the E63, S63 and flagship GT and they’re twin-scrolled. These more aggressive iterations (dubbed M178, while the C63 uses M177) also score a different exhaust manifold, dry-sump lubrication, and fuel-saving cylinder deactivation tech.

No matter the flavour, the result is a donk that feels positively unburstable. Strong, muscular and with a mighty mid-range, it’s also a pleasure to wring out to the 7000rpm rev cut.

Pair this with a chassis that’s now even more capable and, crucially, finally comfortable, thanks to a much-needed dose of compliance, and the C63 is a riot to pedal quickly. It’s also a car that’s easy to drive at the limit, and even beyond it. Engage Sport ESC, or switch it off altogether to activate the nine-stage traction control, and the C63 is equally capable of being fast and neat, or sideways and awesome as it allows you to choose your angle of attack on corner exit.

And for me, it’s that feeling of the rear axle just slipping, of your hands moving to apply a quarter turn of lock, and of the cabin filling with a crescendo of noise and bassy goodness, that encapsulates what sporty V8s are all about.

Kirby: While it’s easy to get swept up in the luxury and theatre of the more extreme cars present, for many Australians, the V8 will always wear a blue collar. The Mustang, here in manual GT guise ($62,990), sticks to those honest roots, and adds a distinctly working-class flavour to our two-day test.

The basic architecture of the Ford 5.0-litre ‘Coyote’ V8 in the Mustang has been around in one form or another since 1990 as part of the Blue Oval’s Modular family of engines. Aussies know and love it for powering the final-generation Falcons, but since the sixth-gen Mustang was introduced to Ford’s local line-up in 2015, the sales figures speak for themselves: offer a sub-$70K V8 and Australians will come.

The core recipe for the 5.0-litre V8 is an aluminium, 90-degree block topped by double overhead cams with variable timing. But Ford snuck an extra 84cc onto the Coyote as part of the MY18 facelift, boosting capacity from 4951cc to 5035cc. Other changes, including enlarged intake and exhaust valves, doubling the number of injectors from eight to 16, increasing the compression ratio to 12.0:1, and a revised intake manifold, result in increased peak power figures of 339kW at 7000rpm and 556Nm at 4600rpm.

Our tester is fitted with the six-speed manual; the only stick present during our celebration. The Getrag gearbox was tweaked for 2018 with a twin-disc, dual-mass flywheel, similar to what is used on the track-terrorising GT350. Yet there’s an endearing simplicity about the Mustang. Westerman praises it for its analogue character in such ‘digital’ company (Trackhawk excepted), while Enright is especially enamoured by the shift action. Over-servo’d brakes and sub-optimal pedal placement are the only lowlights anyone seems able to conjure.

Ford has given the facelifted Mustang four exhaust modes, and when the loudest is selected, it delivers a quintessential bent-eight soundtrack that could headline a V8 Greatest Hits compilation album. Revving it out to the 7500rpm redline before slotting another gear, chirping the tyres, and sliding towards the sunset has surely got to be one of the purest delights in motoring.

While much can be said about the Mustang’s retro looks and comparatively affordable price fuelling its sales success, I’d wager that for many buyers, the real reason they chose to add the Blue Oval’s hero to their garage is the eight cylinders under the bonnet.

There’s an inexplicable X-factor about the V8 layout, no question. The disparate, brilliant V8s in all six of these cars are their beating hearts, and every opportunity to floor the throttle in each raised our pulses. Long may it continue.