LIKE many of the best ideas, AMG started in a humble garage.

Occupying a modest pair of units in the old mill building in Germany’s Burgstall, Hans-Werner Aufrecht and Erhard Melcher’s ambitions of motorsport glory were, in effect, born from tragedy.

AMG, named for the two founders’ initials and Aufrecht’s birth town, Grossaspach, billed itself as an engineering office and design and testing centre for the development of racing engines, a function Mercedes-Benz itself had withdrawn from following the 1955 Le Mans disaster, when driver Pierre Levegh’s 300 SLR ploughed into a packed grandstand, killing 83 spectators and injuring more than 180.

Mercedes put its toe back in the water with Karl Kling’s six-cylinder 300 SE touring car, as well as entries in rallying campaigns such as when Kling himself drove a 220 SE to victory in the 1961 Trans African rally. A decade after the horror at La Sarthe, Aufrecht and Melcher were still negotiating some tricky political hurdles at Mercedes-Benz as motorsport-mad engineers for the brand with an unerring desire to build racing cars.

Both had recognised the competition promise of Mercedes’ 300 SE engine. Although it developed a relatively puny 127kW in production guise, Melcher developed a high-pressure fuel injection system adapted from the 300 SL Gullwing that allowed it to rev to 7200rpm, lifting peak power to 177kW.

Fortunately for Aufrecht and Melcher’s future career prospects, the car was a phenomenal success, with Manfred Schiek claiming six wins in eight races and the 1965 title in short order, in effect establishing Aufrecht and Melcher’s bona fides as borderline genius race engineers. Schiek never got to enjoy the fruits of his success, his untimely death in a crash at the 1965 Tour d’Europe near Prague only bolstering Mercedes’ resolve to steer clear of motorsport activity.

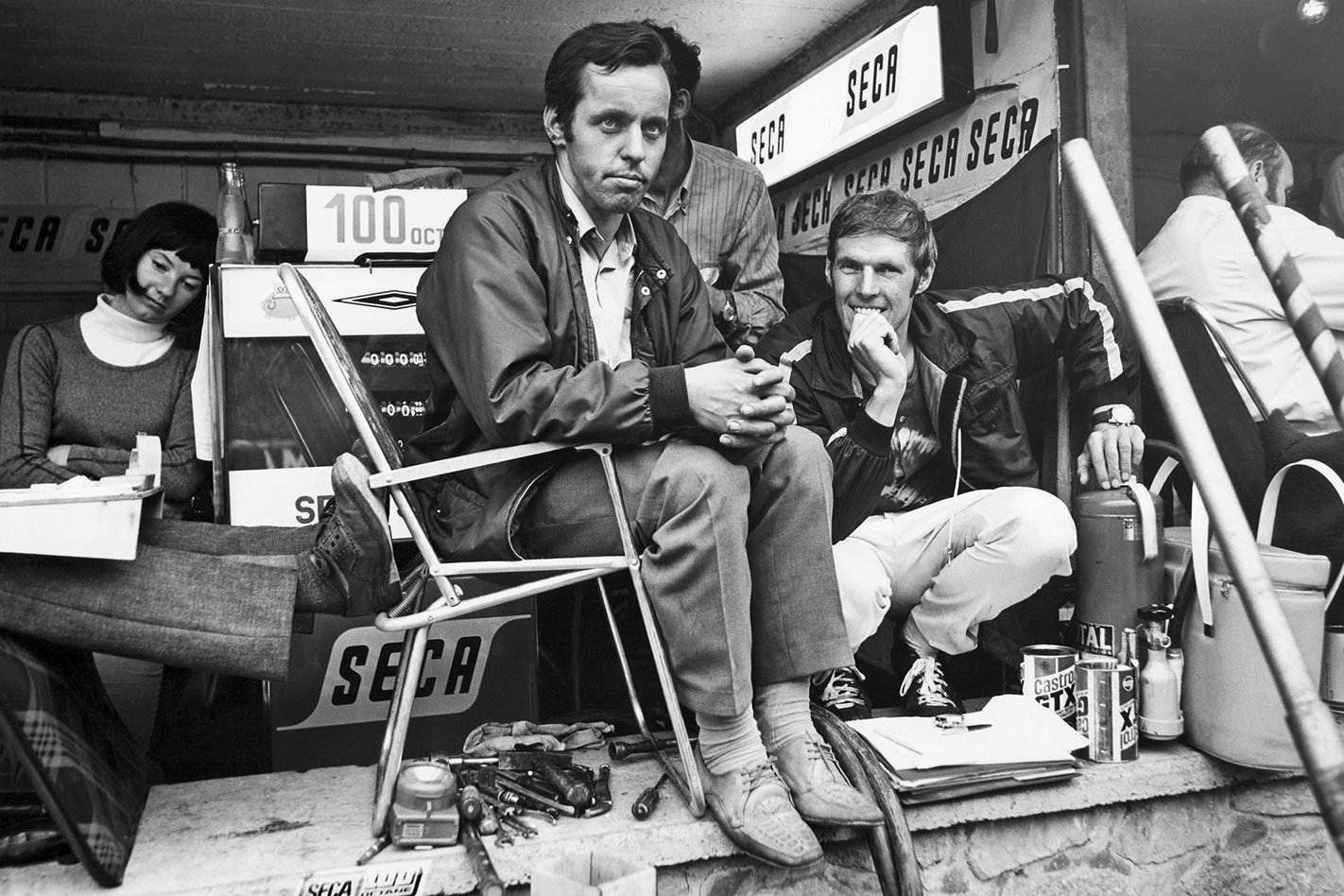

Aufrecht’s vision was always to develop road cars that would sell based on the credibility of track success. In late 1966 he left Mercedes-Benz and persuaded Melcher to join him and by 1967 ‘Aufrecht Melcher Grossaspach Ingenieurbüro, Konstruktion und Versuch zur Entwicklung von Rennmotoren’ was born. Snappy.

Despite only five examples ever being built, the Red Sow entered into legend and cemented AMG’s reputation for overwhelming power and indestructible build integrity.

Its end was ignominious. Helmut Kelleners piloted a 6.8 at Hockenheim, but after an accident on the East Curve, he appeared in the pits, handed Aufrecht the car key and said, “This is your key, but you don’t need it anymore.” Kelleners never drove for AMG again, but the car was repaired. The ’71 Spa car was bought by French aerospace engineers at Matra for its ability to accelerate to 200km/h in 1000 metres in order to model the tyre stresses of landing fighter aircraft on motorways.

AMG became an engine manufacturer in its own right in 1984 with Melcher creating an innovative four-valve cylinder head. The company continued its gradual metamorphosis from a tuning house to a respected developer of vehicles with the 1986 W124 300 CE, the car that came to be known as ‘The Hammer’.

“We listened to customers even back then,” says Aufrecht. “We wanted to build a car that gave you goosebumps. We wanted to have the fastest touring car on the road and we managed to do it with The Hammer. The Americans came up with that nickname and this car was the beginning of a completely new future. That led Werner Niefer [the former MB chief executive known as ‘Mr Mercedes’] to approach us and say, “Hey, can’t we do it together?” You can see today what came of that.”

The almost inevitable contract of co-operation with Daimler-Benz AG followed in 1990, opening the door for AMG products to be sold and maintained through Mercedes-Benz’ worldwide network of service outlets and dealerships. Further expansion led to the opening of a third plant in 1990 and an increase in the workforce to 400 employees.

The first AMG car to be sold in Mercedes showrooms was the rare 1991 model year 190E 3.2 AMG but it took another four years for a jointly developed vehicle to appear. The Mercedes-Benz C36 AMG started life as a C280 sedan, before being transformed courtesy of an AMG-assembled 206kW 3.6-litre straight-six. A rival to BMW’s hugely successful E36 M3, it also ushered in AMG’s involvement as official Formula 1 safety car provider, a relationship that continues to this day. Two years later, the C36 was replaced by the C43 AMG, marking the first time a V8 engine had been fitted to a C-Class.

The introduction of this engine was also marked by a change in the way that AMG cars handled. A more nuanced dynamic palette replaced a prior philosophy where huge power was enough to draw sales without there always being a great deal of emphasis on control.

The following year saw the Mercedes GP Petronas Formula 1 team adopt AMG branding, with a trio of Drivers’ and Constructors’ championships following in 2014, 15 and 16. There then followed an onslaught of AMG product development, with the hugely successful A/CLA/GLA 45 AMG four-cylinder cars and the Mercedes-AMG GT models capitalising on the post-GFC appetite for premium sports models.

The future? You only need look at the dizzying technology of the Mercedes-AMG Project One for a glimpse in that direction. AMG has reached the pinnacle of world motorsport, developed some of the world’s most exciting road cars and has become an integral part of Mercedes-Benz’s product portfolio.

It’s a long way from that Burgstall mill, but in half a century AMG hasn’t deviated one iota from its initial vision. Long may that continue.