The goals for the Gen3 Supercars you see before you are relatively straightforward, if difficult to achieve – look more like their roadgoing counterparts, reduce operating costs and improve on-track racing. Making those goals a reality is non negotiable. It’s no exaggeration to say that the new ruleset which will debut in 2023 is the most important of Supercars’ modern, post-Group A era. Get it wrong, and Gen3 could well become GenLast.

Holden is dead and gone, and in its place arrives Chevrolet Racing, fielding a Camaro ZL1 to take on Ford’s iconic Mustang. The biggest change for Gen3 is clearly the visuals, with the Mustang and Camaro both being realistic representations of the road cars they are based upon. This is thanks to a clean-sheet chassis design built from the ground up to accommodate a range of different body styles. While two-door muscle cars will exclusively take to the grid when Gen3 begins, the steel floorplan and tubular chassis has been engineered in a way to suit both smaller sports cars, and larger four-door sedans should new manufacturers be brave enough to enter the fray.

“We certainly wanted to make sure the cars looked the part as the manufacturers wanted to, so that other manufacturers that want to come in, they see that their cars aren’t massacred, aren’t destroyed,” Jeromy Moore, the technical director at Triple Eight Race Engineering, tells MOTOR. The Banyo-based squad took the initial lead on designing the control chassis, and is the homologation team for General Motors, having been the factory Holden squad from 2017 until the end of last year.

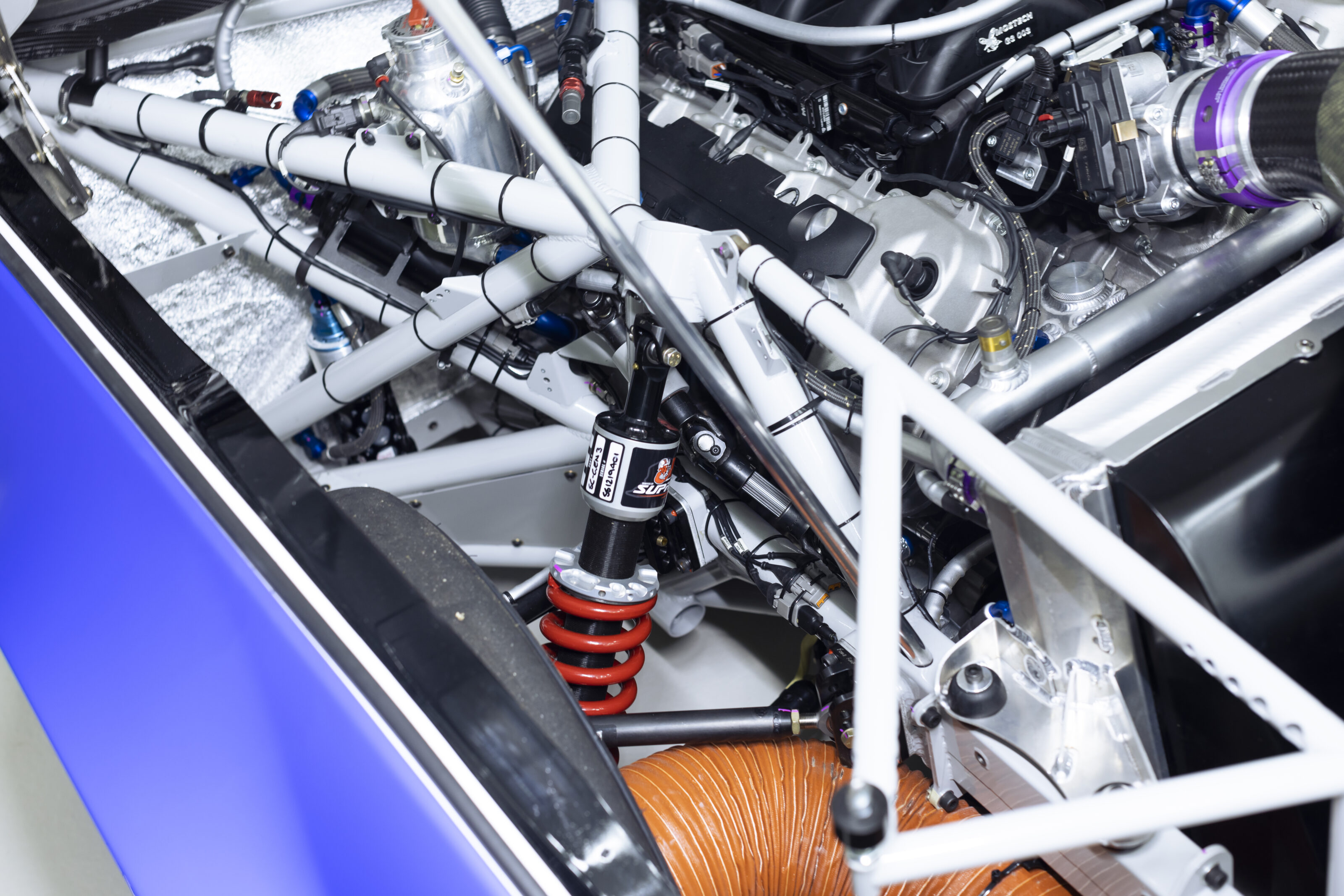

Despite what homebrew engineers may tell you, designing a chassis that accommodates two- and four-door bodies isn’t simply a case of lopping off the front roll hoop that gave the Gen2 Mustang its bulbous glasshouse. Talking to the head of the Camaro program, you quickly learn that under the bodywork is a tangled web of symbiotic relationships where moving a single component has unintended and surprising knock-on effects elsewhere in the car.

“Everything is really critical where it goes, and you have to think about the steering system when you’re designing the engine water reservoir, for example. It’s all one big, interrelated organism,” Moore explains.

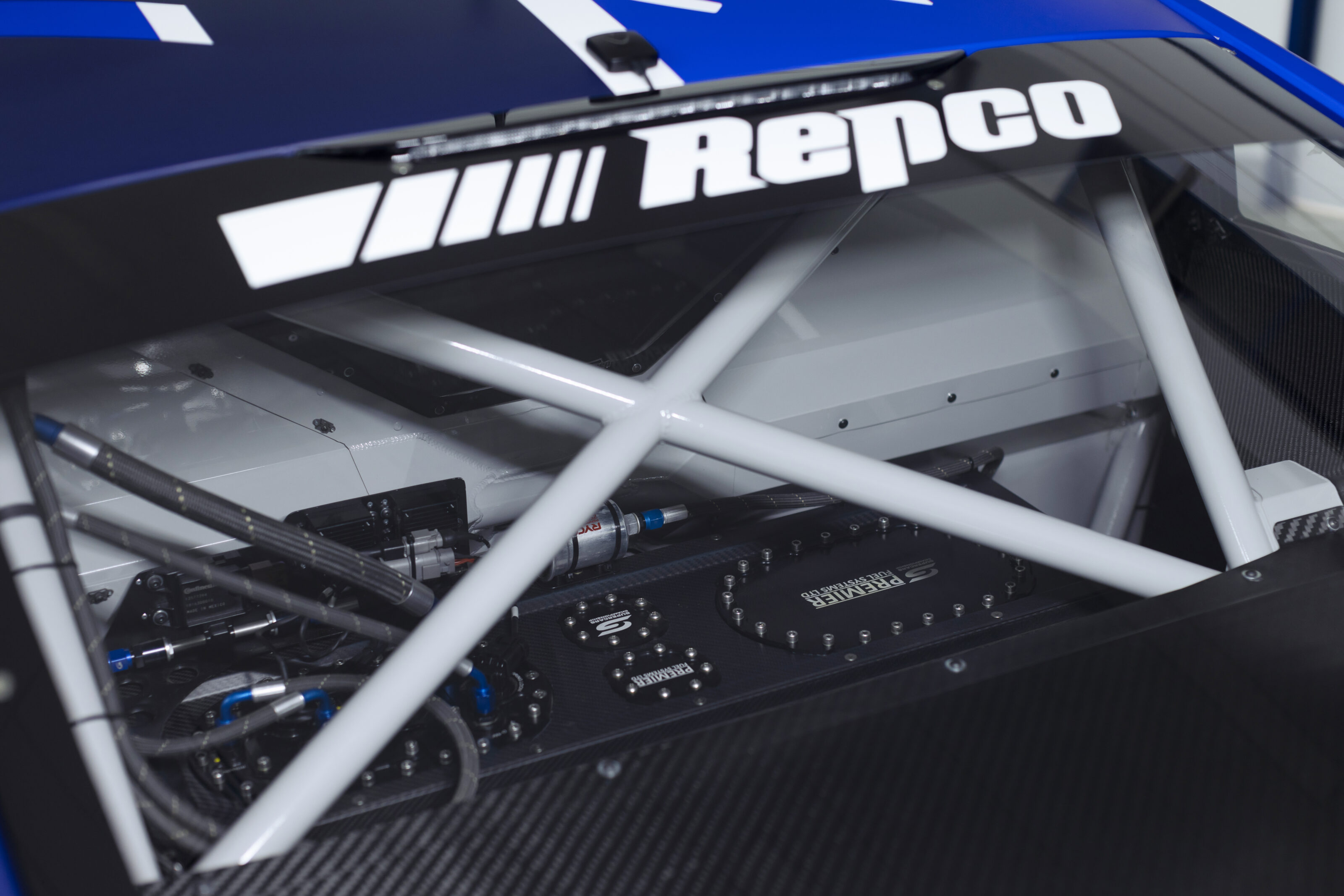

Perhaps the most drastic example of this is the need to accommodate a battery pack and electric motor should Supercars decide to allow hybridisation in the future. To package this, a space has been left vacant in the floor below the driver. This, surprisingly, is linked to a move of the exhaust, which keen observers will note has shifted from in front of the rear wheels, to just behind the front. A transposition which in turn, is a direct result of lowering the roof line.

“Currently on the current Gen2 cars, the muffler is sitting underneath the passenger seat, which is fine when you’re racing, but it has a lot of knock-on effects where you put a passenger in there, and especially if they’re tall, their head is right in the roof and through the roof bars. So safety-wise, that was a big compromise,” Moore adds.

The roof comes down by 102.5mm, which means so does the passenger. Ergo, the exhaust now must exit much closer to the engine, with the floor raised in that section appropriately. “So to make the car symmetric, we also allowed the volume below the driver’s side to have room there to put batteries under there when we go that way,” he concludes.

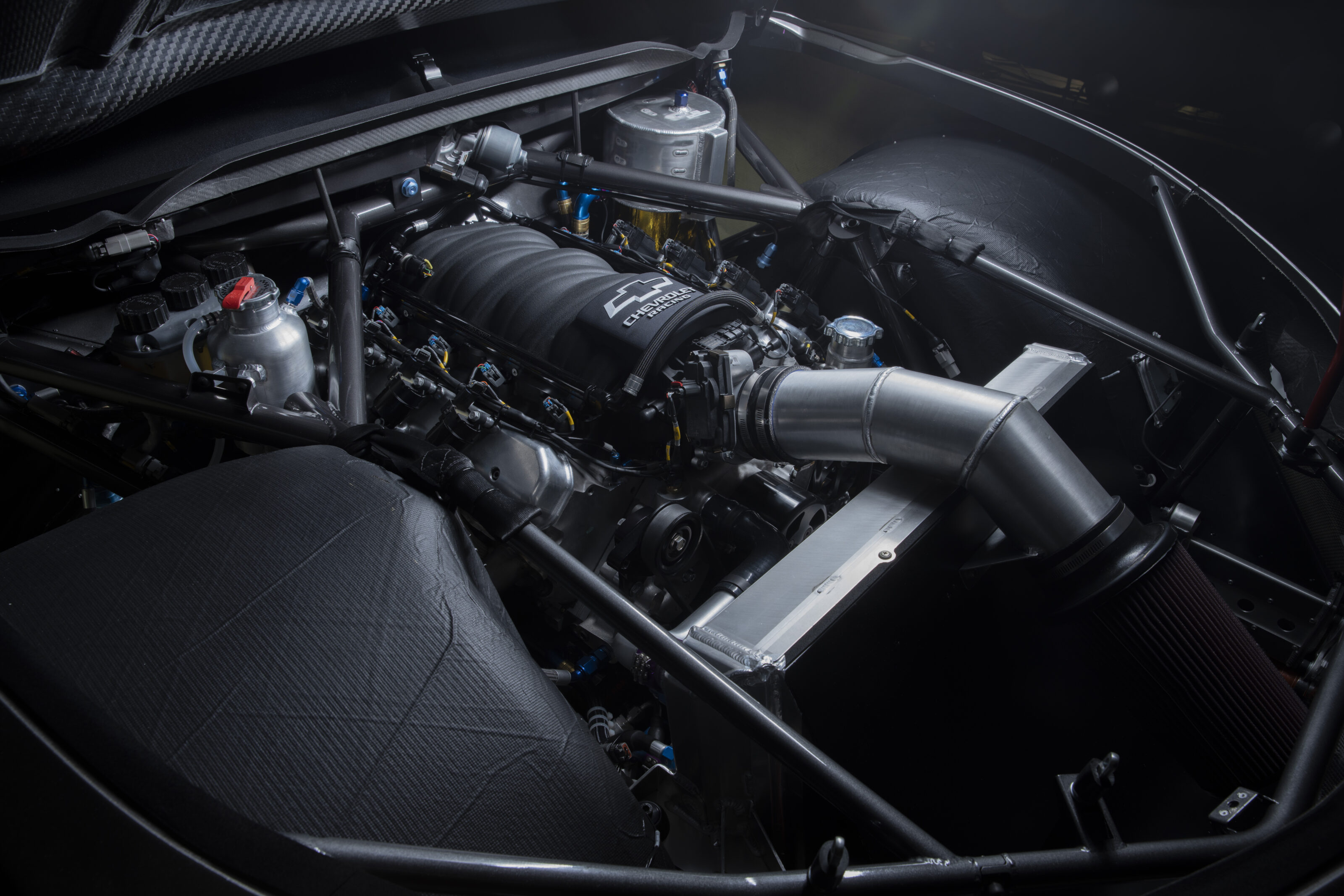

To go with the new coupe bodies, Supercars has also upended the engine formula that has powered the category since Group 3A regulations were introduced in 1993. The 5.0-litre pushrod V8s are gone, replaced with OEM-based units for both Ford and GM. While the current design is well established, it’s also incredibly expensive, with two car teams spending up to a million dollars a year on engines alone.

These new units hope to slash that to roughly $250,000, and will run on the same E85 fuel currently used in the championship. Cheaper engines come at a cost that isn’t entirely monetary, with power reduced by circa 40kW to 447kW.

The most drastic change is on the Blue Oval side, which now uses a 5.4-litre dual overhead cam engine based on the Coyote V8 in your regular everyday Mustang GT. Developed and built by Mostech Race Engines in conjunction with Ford Performance and Dick Johnson Racing, the Ford V8 uses variable valve timing, an aluminium block and cylinder heads, custom stroke crankshaft, custom connecting rods, Mahle pistons, plasma arc coated cylinder lining, and dry sump oil system. Gone are the individual throttle bodies, with a single OEM inlet manifold, throttle body, and injectors, while the whole thing runs an 11:1 compression ratio.

Chevrolet teams will retain a pushrod design, but with the capacity jumping to 5.7-litres. Dubbed LTR, the GM unit is built from a melange of LS and LT small-block engine parts. For example the cylinder heads are GM Performance CNC versions of what is found in the LS9 that powered the HSV GTSR W1 sedan. Despite the larger swept capacity, the GM LTR engine is physically smaller than the V8 used by Ford teams.

Initially Supercars intended to create an in-house control engine for every team to use, regardless of body style. This was intended to be the Coyote-based V8 used in the Mustang, but objections from both sides of the aisle saw a smarter multi-engine solution implemented.

Behind the engines, the transmission will remain at six ratios mated to an Xtrac transaxle – one of the few carry-over parts from Gen2. However, how the cogs are shifted was a hotly contested debating point as of the time of writing. You’ll note in the interior shots that the Camaro is fitted exclusively with paddle shifters, while the Mustang has a traditional sequential stick (as well as some very discreet paddles). The Supercars technical department has been working hard behind the scenes evaluating both manual and auto-blip solutions for 2023.

The reason a reduction in engine power isn’t that big a deal is because Supercars has also heavily slashed the amount of downforce the cars will produce. While Ford and GM design teams penned each car’s body internally, it was Supercars that held final authority over the rear wing profile, with the manufacturers styling the end plates.

At 200km/h current Gen2 cars make approximately 450kg of downforce. For Gen3 that figure will be closer to 140kg, on par with the 991.2 Porsche 911 GT3 RS. Part of that reduction is the wing profile, but also the complete loss of the front undertray.

“Fundamentally, the cars will generate probably most of their downforce just from the body shape itself,” Perry Kapper, chief designer at Dick Johnson Racing, explains to MOTOR. This mean bends that were once taken flat – like The Chase at Mount Panorama – will become a lift, essentially adding more corners to the championship. Additionally, less dependence on aero means following another driver closely won’t have as large an impact on car control.

The prototypes are also a couple hundred kilos lighter than the current cars, while it is estimated in production spec they will be roughly 100kg lighter for a minimum weight of 1295kg including the driver.

Along with the reduction of aero, Supercars has boosted the Gen3 car’s mechanical grip by lowering the centre of gravity and making them wider than the current racers. The track of the Gen3 cars is yet to be finalised but currently sits around the two-metre mark, while Gen2 sits at 1913mm. The wheelbase has changed also, down from 2822mm to 2765.5mm.

“We’ve gone halfway between the Mustang and the Camaro wheelbase, so that not one manufacturer has to compromise more than the other,” Moore explains. “And we’ve done it in a better way than the current cars, where you’d normally cut the middle of the back door and then you move the whole back of the car forward relative to the front wheel. Whereas now, it’s just absorbed. We’ve moved the wheel arch forward on the Camaro, and backward on the Mustang so it’s very hard to tell any difference when you put the two cars beside each other.”

That wheelbase will also be modular. While the Camaro and Mustang are identical for ease of parity to start Gen3, should a new manufacturer enter and be unable to match the dimensions without butchering their bodywork, Supercars will either stretch or shorten the chassis as required to accommodate the vehicle appropriately.

The footprint of the car is just the tip of the iceberg. The list of carryover parts from Gen2 to Gen3 amounts to the transaxle, rear suspension wishbones, and the rear uprights, the latter with some minor CNC modifications to help accommodate the new brakes.

“Really, that’s about it because everything else is all from scratch,” Moore continues. “Front suspension, it’s all a control item now so that people aren’t going and re-engineering a new suspension every six months and investing money there. All of the drivetrain is new. The prop shaft is a bit different – it’s a bit shorter and it’s obviously mounted slightly differently, but it’s the same concept. But again, not the same part.”

Cast your eye over the cars and little details begin to emerge, with a startling number of tweaks. The striking new rim design isn’t merely for show. The offset has been changed from 52mm to 25mm in order to reduce the likelihood of spindle clashes when drivers rub wheels. In fact, the spindle itself is also new for Gen3 to accommodate a smaller wheel nut thread of 45mm (down from 72mm).

The flow-on effect continues, with a smaller thread meaning lower tightening torques required from the wheel guns during pit stops, allowing teams to ditch high pressure nitrogen gas units for electric versions. Even the radiator needed to change. A move to an aluminium engine design means more heat is being transferred from the block into the water, necessitating a 30 per cent increase in size.

Attached fore and aft of the core chassis is a new-for-Supercars quick change front- and rear-end design that is commonly referred to as a ‘clip’. “The idea is that if you have a decent accident, then what you can do is you can just unbolt a front clip and remove it and then fit a new one,” Kapper explains. “So that should, in theory, make it a lot easier to repair the cars at the race track and you’ll need less skilled people on hand to be able to fix the cars.”

Along with the easier to repair construction, the development teams have been playing with new materials and panel designs to reduce the impact, both financial and physical, of crashes. “There are more individual panels on the car which are composite, but you can replace them, so you’re not damaging a bigger part that costs a lot of money,” Moore adds. “You can replace a smaller part, and it all comes down to clever layup as well of the composite. If you come up with, which we have on the car, several parts which are impact resilient and flexible, there was a clever layout like a rubberised Kevlar, where you can physically smash it with your hand and it just pops in and out, and off you go again. So it’s all about not only the design, but also the manufacturing of the parts which has a big influence on the cost.”

While the Gen3 cars are visually finalised, and this procedure is expected to be extremely minor tweaks following aerodynamic validation testing, there are a number of components underneath the composite body panels that are yet to be finalised. Most importantly, what will be used to steer the front wheels.

“On the original design concept, we agreed we were going to go with an electric powered rack, but then COVID arrived,” Burgess says. “And we had a few supply issues with one of the manufacturers that we were heavily in negotiation with. And we had CAD and we had a design of the rack we wanted to use, but then those guys weren’t able to support the program with the timeline that we had in place. Now, with the program going back to 2023, it might enable us now to just revisit some of the decisions we had to make probably 12 months ago in order to get the prototypes finished.”

Whatever the choice, Supercars will have to contend with its competitors edging toward self-destructive set-ups. Teams have been pushing the current systems to the limit with ultra-aggressive suspension geometry for a while now, some going so far as putting 25 degrees of caster on their car in order to improve, for example, camber gain. The Gen3 chassis philosophy hinged on reducing these extreme geometries.

“We knew coming in, in the last few years in particular, every team is pushing the limit on the loads of the steering because you’re getting performance by, for example, increasing the caster trail and other kinematic elements, so that the steering is literally on the edge,” Moore adds. “We haven’t locked in exactly what the steering system is going to be, rack, etcetera. But first step for sure, is to make sure that the load is less going through whatever steering you pick.”

Throughout the entire Gen3 development process Supercars has focused on simplifying what it takes to build and run its race cars. Any area where teams or manufacturers could previously design their own components has been buttoned down and replaced with control spec parts. By removing this developmental freedom, the category hopes,in turn, to change the focus to teams working on nailing the set-up with what they have, instead of building new parts.

“We’ve kept quite a lot of the adjustability,” Kapper says. “The amount of adjustment range you have with the positions of the rear suspension arms, which allows you to do your squat for drive, and anti-lift in the rear, and roll centre adjustment remains. We’ve still got spring rate changes that we can do, anti-roll bar changes and things like that.

Put simply, there is still enough adjustment available that teams will be able to get lost in the set-up process.

“What we’ve taken away at the moment with the prototype cars are the anti-roll bar rockers,” Kapper adds. “So removing the anti-roll bar rockers means that the engineers have a lot less freedom to design something that is nonlinear, in the actuation from the roll bar point of view. So that’s going to be quite a big change to the handling of the cars. It’ll make a big change to the balance of the car and how it is to drive.”

As a result of the rocker changes, and the retention of the spool rear differential, Kapper says the Gen3 cars will have plenty of visual attitude on track.

“They’re definitely going to move around more under brakes, slide more on the exit, and understeer more mid corner. There’ll be a lot more going on.”

Influencing the decision to remove core design freedoms from areas such as the front uprights is Supercars’ commitment to slashing operating costs for teams. Yes, building prototypes is expensive, Supercars knows that. It also recognises that the transfer period between Gen2 and Gen3 will not be a cheap one. However, as Burgess points out, the fate of budgets remains in the hands of the teams.

“The other key area for cost saving is going to be the rule book and how the rule book is written and how you operate the car,” he explains. “In our current form of racing, there are so many freedoms with the car that the teams are able to just constantly play with parts and change and try and modify to find the smallest amount of lap time compared to somebody else. And that costs money in itself. You’re a design business. You’re an R&D business. And you need to be the manufacturer to build all these things.

“I think the teams will start to restructure themselves and become more race team than an R&D testing house. But how much [they’ll save], you can’t quantify that because I think we all know that if a team’s got a hundred dollars, they spend a hundred dollars. They don’t spend $90 and put $10 in their back pocket. They spend everything they’ve got. So, is it really going to be cheaper? That’s in the hands of the teams to drive the outcome. They’ve got to change their mindset.”

As a former chief mechanic and sporting director for several F1 teams, as well as his stints locally managing DJR, Walkinshaw, Triple Eight, and Tekno Autosports, Burgess is intimately familiar with where teams will be looking to try to find loopholes in his regulations.

“We’re trying to save them from themselves. And that’s pretty much it. I mean, I’m a racer. I’ve been racing all my life. And so I know what it’s like and I sort of understand where they’re all heading, or where they will head if we leave any doors open. So, part of this next year is about trying to close all the doors that we want to close and just leave open the doors that we want to leave open.”

Building the cars that grace this page was a long process, but arguably the most important 12 months are still ahead for the development teams. It’s not just technical reliability and validation that requires scrutiny though, with the car’s on-track racing ability set to come under the microscope.

“We’ll get the cars to race each other and simulate a good old classic race,” Burgess says. “We have sort of been doing that in CFD already. We know, in CFD terms, how much closer the cars can follow each other than the current. We spent a lot of time simulating that in CFD. And at the moment, the results are definitely showing that these cars will be able to follow far closer than the current car, but that’s in CFD. So we do have to go and validate that in real life conditions.”

The final piece of the testing puzzle will be Supercars’ Vehicle Control Aerodynamic Testing (VCAT) regime that ensures the cars are aerodynamically equal. Burgess and his team heavily updated the process last year to ensure competitors aren’t able to slip an unfair advantage into their final homologation.

While we can all agree that the Gen3 cars look spectacular visually, Supercars will spend the next year sweating the details to ensure they are as cheap to run as promised, and the racing lives up to the hype. When the Gen3 Camaro and Mustang take to the track in 2023 it will be 52 years since Bob Jane and Allan Moffat finished first and second in the Australian Touring Car Championship. Their steeds? A Chevrolet Camaro and Ford Mustang respectively. Everything old is new again.