Winton Motor Raceway: a pleasant little rural Victorian racetrack, generally regarded by V8 Supercar aces as tight, technical and challenging. Yours truly: a pleasant, not-so-little scribe, generally regarded by MOTOR staffers as a fair-to-middling driver, but no ace.

This feature was originally published in MOTOR’s June 2002 issue

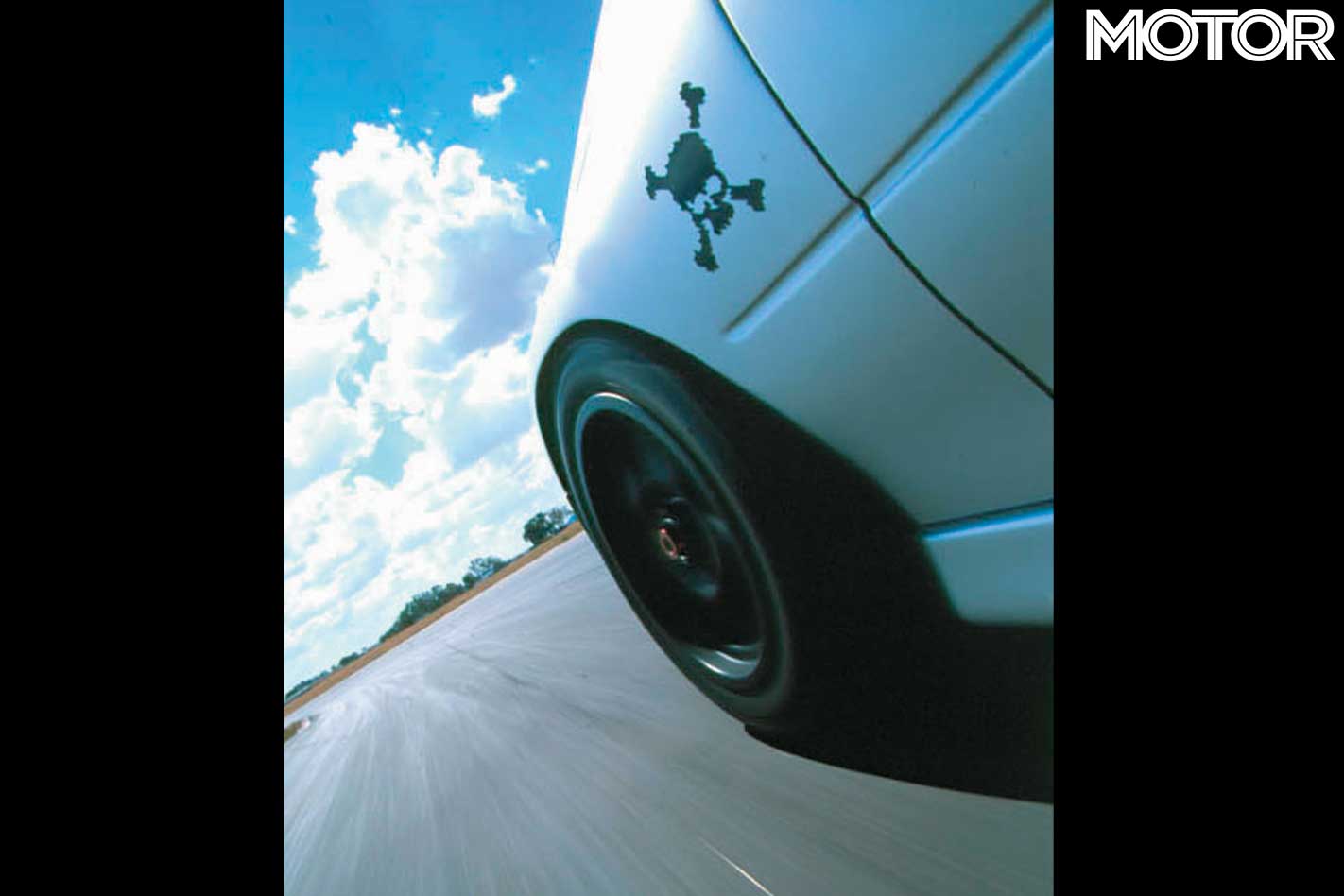

Holden Motorsport’s V8 Supercar ‘Thunder’ Ute: the world’s fastest pickup. It’s 1300 kg of hot metal propelled by a barely detuned, full-race Chev punching out 380kW. It’s the only one on the planet, it took Garry Rogers Motorsport eight months to build it, it’s worth $300,000 and I’m to be the first non-racing driver to steer it.

Holden Motorsport PR, Gerald ‘Donut’ McDornan, has put his balls on the line to pull off this world first, and his slightly panicky “Don’t bend it, Nally!” mantra buzzes inside my head like a small mossie in a very big jar. In seven days the Thunder Ute has to be in Adelaide for promo duties at the Clipsal 500 – and in one piece too, thanks mate.

If McDornan is nervous, imagine how I feel…

This is the most powerful car I’ve ever driven, and I’d spent a restless night fretting over missing shifts on the tricky Holinger six-speed gearbox and over-revving one of engine builder Mike Exell’s babies. Not to mention the scorn of the country’s top racers if I cocked up. God knows they’d love that.

You see, this isn’t a private test day, where indiscretions are just between you, your deity of choice and the stopwatch. No sir, this is the last test before round one of the V8 championship for Garry Roger’s outfit, as well as for HRT and Kmart Racing. I’m feeling about as exposed as a pimple on Kylie’s arse.

When I arrive, sprintcar legend Max Dumesny is fanging the unmarked Ute around the twisty circuit, and in the distance it looks like a secret prototype, hot from Holden’s skunkworks. In the pits I casually admit my concerns about the gearchange and the power to Rogers and Co.

“Mate, it’s easy,” beams Dumesny, “It puts its power down so smoothly, don’t worry.”

GRM drivers Garth Tander and Jason Bargwanna take a breather from testing and reiterate how easy (there’s that word again) the Ute is to drive and how much fun I’ll have.

Exell tells me the power is very progressive and that it has more grunt down low than the racecars due to a tamer cam. And, by the way, the MoTeC dash isn’t working so change up when you feel the limiter kicking in. It’s set for 6500rpm, 1000 down on the GRM racers’ to extend engine life. I protest that I won’t get out of fourth gear but Exell assures me I will.

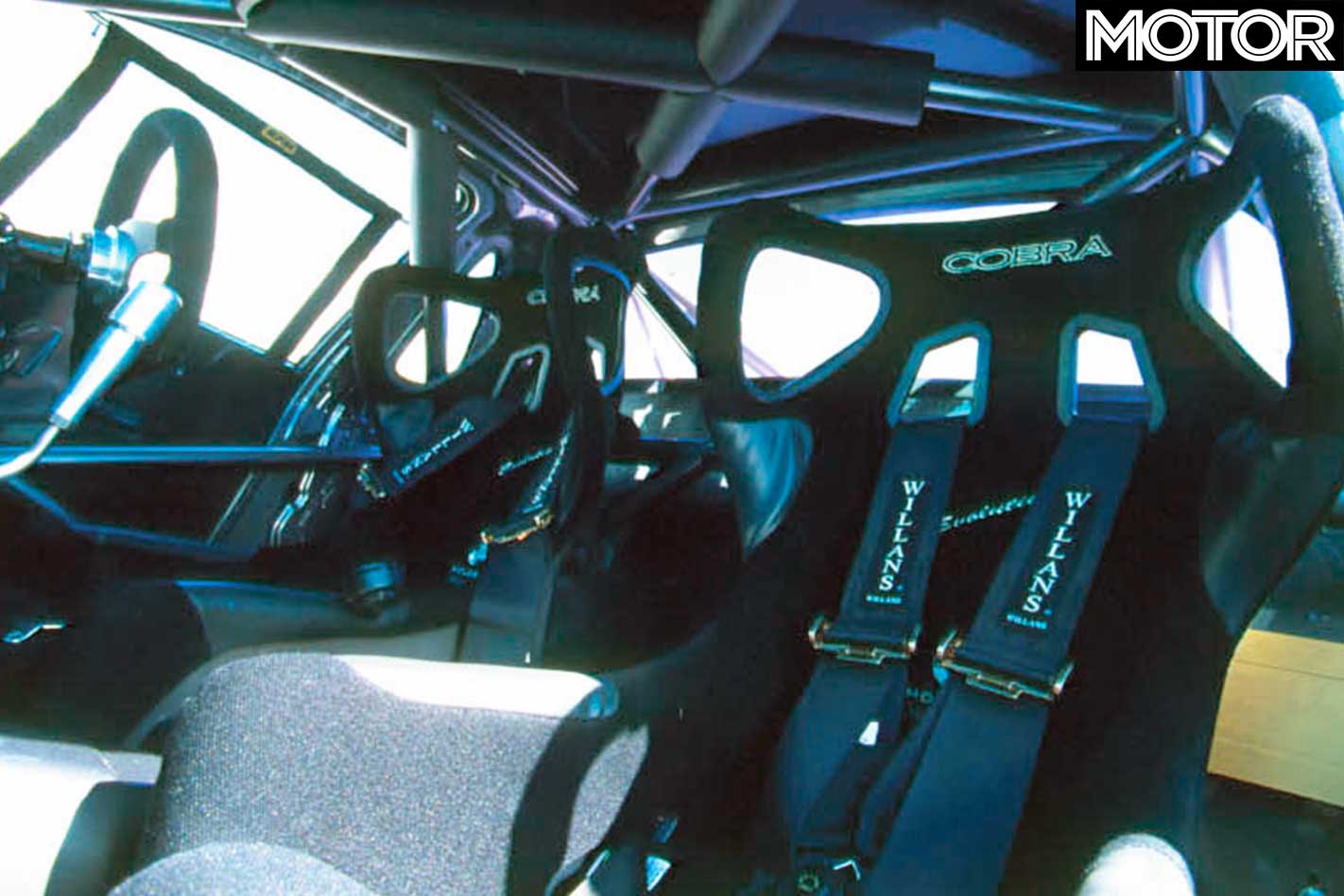

Rogers proudly shows me over the car. The fabrication, panel and paint quality of the Thunder Ute is good enough to win Street Machine of the Year. The interior is race-Spartan and hearse-black.

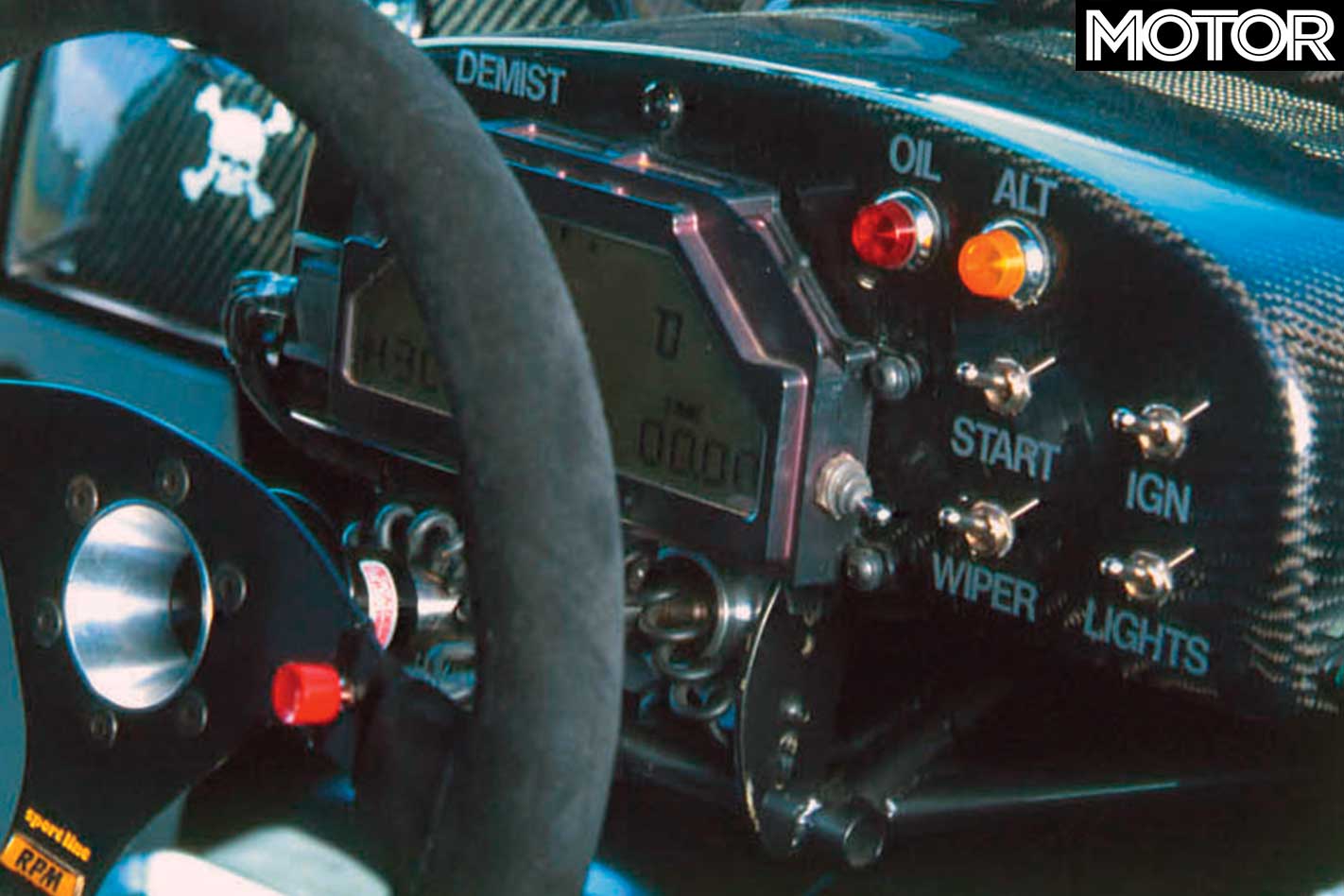

The ‘dead’ data dash sits on an extended steering column and is surrounded by oil and alternator warning lights and toggle switches for ignition, start, lights and wipers. A green brake balance dial resides on the side of the dash. The red button on the wheel activates the front brake line locker for burnouts; best not mistake it for the pit lane speed limiter button, then.

The carbon-fibre dash houses oil pressure and water temperature gauges. Everything is in easy reach. The detachable, D-shaped RPM Sportline steering wheel is perfectly positioned for me, as are the floor-mounted pedals. Thoughtfully, GRM has fitted power steering. But there is no rear view mirror.

My turn. In a shiny new yellow and black RPM race suit (thanks Revolution Racegear) I look like a giant bumblebee and I quietly pray I don’t emulate that insect’s wayward flying pattern. I’ve got just five laps to shine or look shite.

Arse wedged into the narrow Cobra bucket and snug in the five-point embrace of Mr Willans’ finest three-inch harness, I’m as ready as I’ll ever be, and the Ute is pushed out of its garage. This is so surreal. I’ve seen this scenario played out so many times that I feel like I am actually going out to race. Up and down pitlane, everybody has downed tools and interrupted debriefings to watch the journo bend the ute. Gulp.

Ignition on, starter on and the Chev bursts into raucous life. Oh, what a lovely, lovely noise. It’s loud and hard-edged and a quiver of excitement rushes up my spine. I don’t feel nervous, but my mouth is dry. Clutch in and first gear engages with a hard, car-juddering clank. The chassis starts a little shimmy, as if it knows what’s coming. I wish I did.

Now, it’s customary to stall one of these things first time out, and who am I to break with tradition? I raise the revs and slip the clutch. It takes up immediately and the Ute lurches an inch and dies. A huge cheer goes up. Bugger! Mind on the job now.

Ignition, starter, more revs, slip the clutch, and I’m away. The car begins to jerk and buck and I remember Exell’s advice: “If it starts to bunny-hop, bang it straight into second.” I do – cl-ank! – and idle smoothly past the V8 idols onto the track.

It’s lunchtime and (thank God) I’m alone on the track. Squeezing the stiff throttle oh-so carefully, I squirt up to third before lifting off and rolling carefully through the Esses. A short blast uphill past the old start/finish line and the first 90-degree right-hander comes up very quickly. I push on the brake pedal – but nothing happens! I push much harder and the car j-u-s-t begins to slow.

Of course, there’s no heat in the brakes. Then another piece of Exell advice comes back to me: “Brake earlier than you think you have to because you’ll be going faster than you think.” Too bloody right…

Back to second – clunk – blip the throttle, turn in; add more gas and get going. Round the next right-hander, snatch third, and take aim at the fastest corner at Winton, the long double-apex sweeper. There are plenty of marbles off line and I treat the sweeper with circumspection. It must look so slow back in the pits.

Through Penrite corner, ’round the ‘Gumtree’ hairpin, and on to the old back straight, feeding the power on, and trying to be smooth. Up to fourth before braking for the sucker-punch left that cuts back savagely and leads on to the new back straight.

Avoiding the jagged ripple strip on the exit I accelerate hard up to fourth. Yeeeee haaaaah! Five hundred horsepower turns a 200-odd metre straight into a suburban driveway. Blink and you’ll miss it and your braking point.

The next two 90-degree rights are taken in second then there’s the intoxicating 180km/h fifth gear rush past pitlane to the Esses and the biggest stop of the lap. I brake at the 300-metre board; Tander and his mates brake between the 100- and 200-metre markers.

Lap one done, all systems a-okay, I start nailing the throttle harder and earlier. Dumesny is right; the car just squats and goes, but I’m still mindful of the mumbo and make sure the front wheels are straight before I really start gassing it hard.

Lap two is logged, a big, shuddering understeer at the Tree the only blemish. I’m beginning to enjoy myself but it’s 35 degrees C outside and more like 45 inside the car, and I become aware of the physical effort I’m putting in. Despite power assist, the steering isn’t road-car light and my forearms would be sore for days.

So far I haven’t cocked up any downshifts. The Holinger ’box is amazing. As revs build it emits a psycho-with-chainsaw whine and each shift sounds like someone is bashing on the floor with a sledgehammer. Actually, the whole V8 cacophony is thrilling; there’s nothing like the sound of eight race-spec pistons mashing air and fuel into atoms.

Then I miss the second-to-third shift. It should be just a flick of the wrist but for some reason I blow it, find first, and buzz the engine. The valve springs go ballistic; I cringe like a bad puppy.

The two-three change became my bete noir, and the expensive shriek of missed gears would grate on my nerves twice more. But, as Larry Perkins would say, press on and see what happens.

Lap three: I try using the brakes harder and the back end starts to move around. Bargs would tell me back in the garage that the brake balance was biased too much towards the rear.

Lap four, back straight, 170km/h in fourth, brake hard, third gear, second gear, tyre squeal… hello, I’ve spun! Shit! Man, that happened so fast, the back end just swinging around. I’m stalled, still on the track, but I didn’t hit anything. Bonus!

A moment of panic; ignition, starter, stall; ignition, starter, stall it again. Shit! Ignition, starter, big rev, slip the clutch and movement at last. I think I snagged the throttle and brake pedals together or I got compression lock-up in second, or both. Memo to self: buy some narrow racing boots.

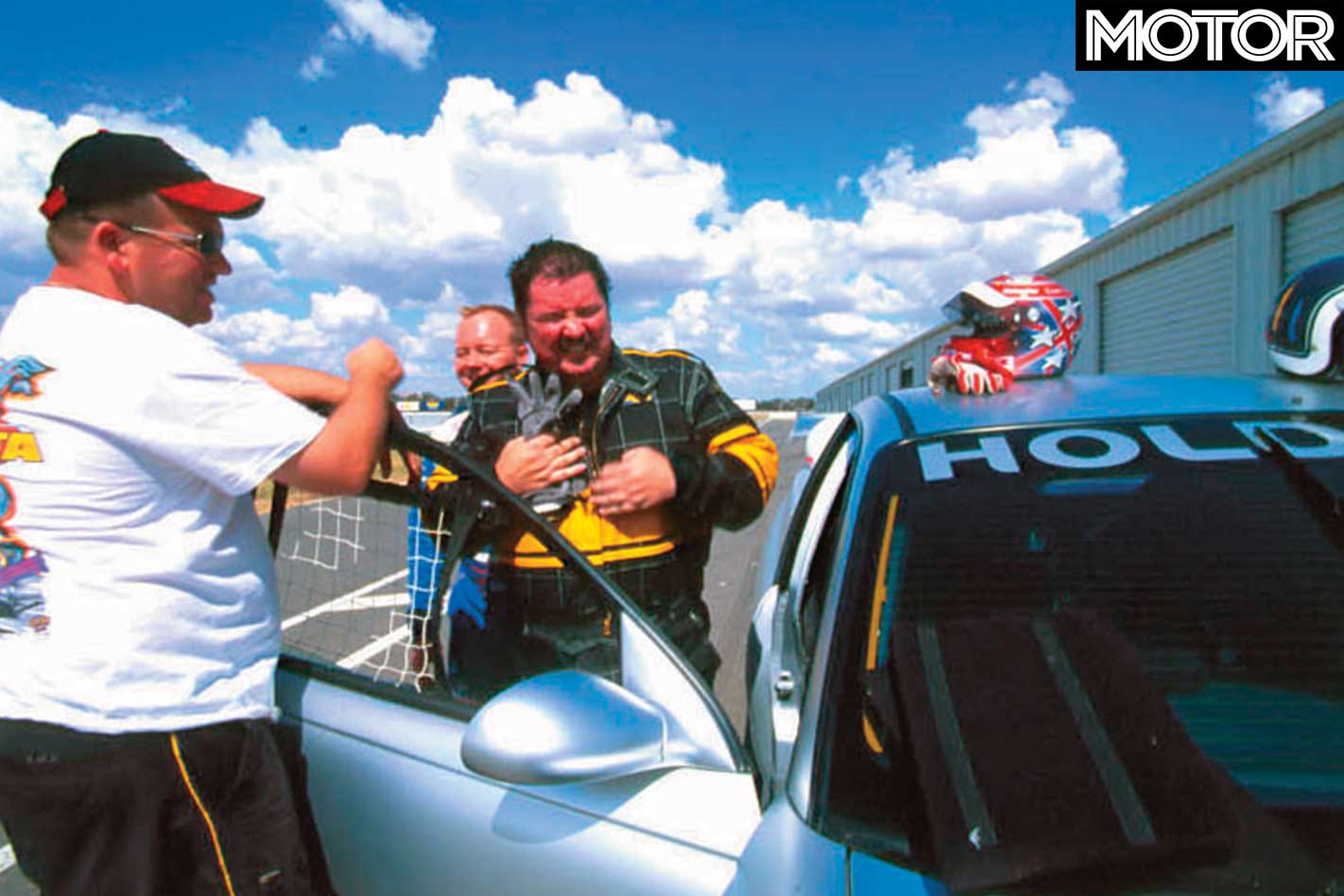

I do one more lap, and then rumble slowly down pitlane to an unknown reception. But more embarrassment is to come. Exiting the car awkwardly, I slip on the car’s metal floor and fall flat on my back, my head crashing down hard on the concrete. Rogers bends over me, pissing himself laughing. “So that’s what helmets are for!” I yell up at him. Memo to self: buy some narrow, sticky-soled racing boots.

I’m knackered. My arms are limp, I’m drenched in sweat and my head is ringing. Rogers is still laughing, he thinks it’s great fun. Bastard. McDornan is relieved. Exell plugs his laptop in to check the over-rev. Bad?

“Only 7900,” he shrugs. “That’s nothing ’cos the limiter was set at six-five. Don’t worry, the pros do it all the time, except they buzz ’em over 9000rpm.” The team says nice things.

“It’s not easy to get into one of these things with no experience and go fast in five laps,” Bargs says. “They’ve got angry brakes, an angry gearbox and an angry throttle.”

Tander concurs. “Winton’s not an easy track, either,” he says. “You’re always turning, braking or shifting, you don’t get any rest. Actually the racecars are easier to drive.” Now he tells me!

Did I explore the Ute’s limits? No. Did I get near mine? No, I was being way too circumspect; hey, it’s someone else’s $300,000 ute. But I had a bloody great time. The Thunder Ute intimidates like no road car can, but with more laps I reckon I could cut six seconds off my time. Familiarity breeds speed, you know.

Hey Garry, if I start training now, I reckon could be ready for Bathurst. Garry? Garry? Where are you going, Garry? Garry, what about a Konica drive? Garry!

FAST FACTS 2002 Garry Rogers Motorsport Holden Thunder Ute

BODY: 2-door ute DRIVE: rear-wheel ENGINE: 5.0-litre V8, MoTeC engine management system BORE/STROKE: 100 x 75mm COMPRESSION: 10:1 POWER: 380kW @ 6100rpm TORQUE: 597Nm @ 5250rpm WEIGHT: 1350kg POWER-TO-WEIGHT: 281kW/tonne TRANSMISSION: 6-speed manual SUSPENSION (f): Harrop hub on GRM MacPherson struts, 3-way adjustable Ohlin shocks, adj anti-roll bar SUSPENSION (r): four-link, adj. Watts link, coil-over adj. Ohlin shocks, adj anti-roll bar L/W/h: 5040/1870/1410mm WHEELBASE: 2939mm TRACKS (f/r): 1559/1577mm BRAKES: 375 mm ventilated discs, four-piston mono-block calipers (f); 340 mm ventilated discs, four-piston calipers (r) WHEELS: 17 x 11-inch (f & r), alloy TYRES: Bridgestone 17 x 12 (f & r) PRICE: $300,000

Five reasons to unnaturally crave the Thunder Ute

01- It’s the only one there is 02- It’s straight-up Supercar top to toe 03- The noise. Oh, the noise! 04- Close as God to a Level 1 car 05- Punching it in third

Mike Exell, the man behind the engine

Mike Exell builds GRM’s engines and says the Thunder Ute’s donk is pretty close to the real V8 Supercar deal.

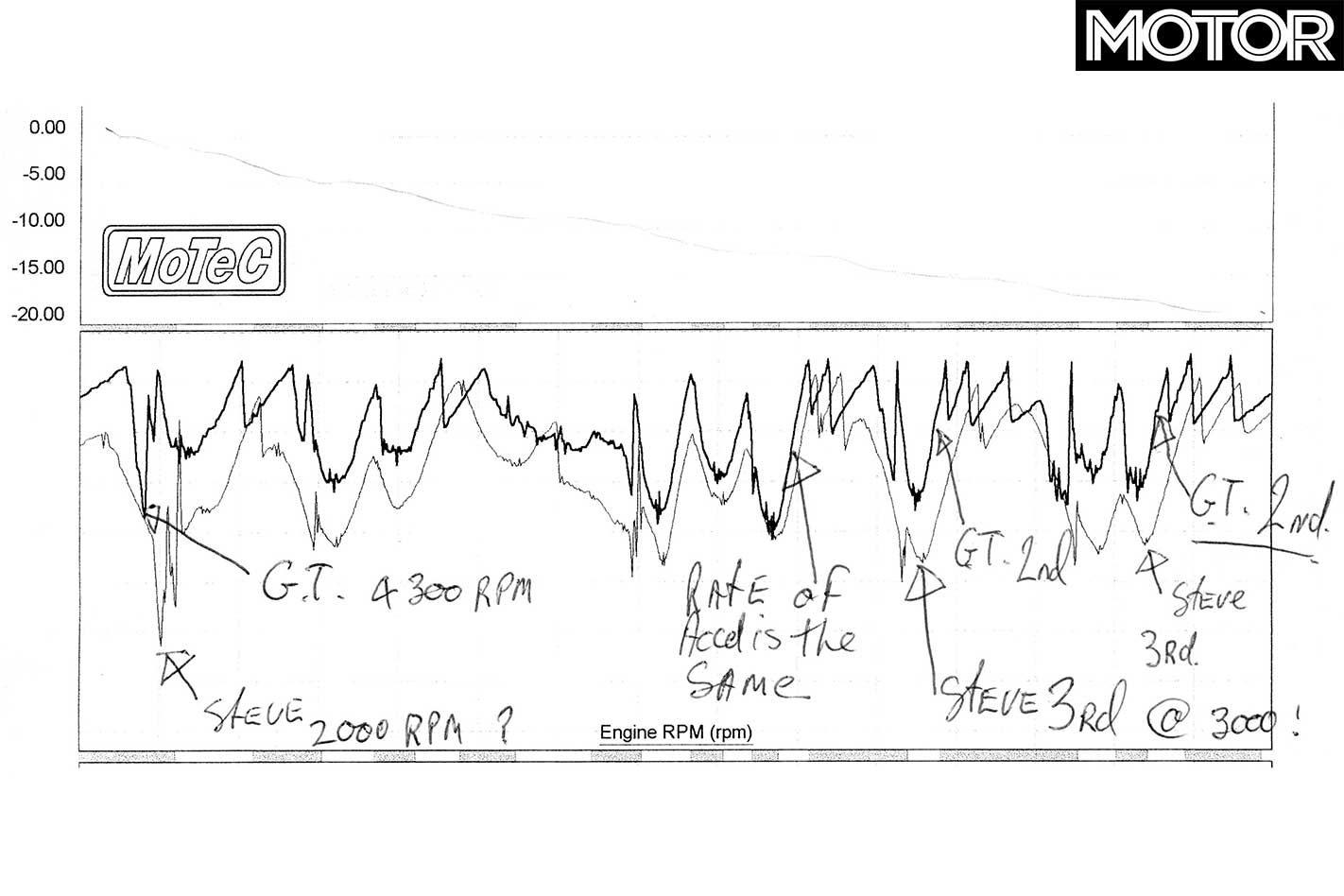

“The Ute’s engine has a different configuration to the race engines to make it last longer between top-end rebuilds (4000 km instead of 2000). It’s only got about 160-180 bhp at 3000 rpm but it steps up big time from 4000 on where it’s got about 380 bhp, and about 440 at 5000 rpm. It makes about 510 bhp at 6000 rpm, which is about 10 bhp less than our race engines at 6000. But the race engines keep going (making more power) where the ute’s flattens off. But lowering the revs makes it a bit stronger than the race engines, because it’s got a milder cam, and at 4500 rpm it’s probably got 30 bhp more than the race engines. It makes about 440 ft lbs of torque; a really good race engine will make 450.”