This week marks a decade since the sad passing of Peter Brock, so to celebrate his amazing life we’ve delved into the archives.

This story comes from our January 1983 issue, in which we ran full performance figures on the new VH Group 3 Commodore SS and compared it to its race-going sibling, Peter Brock’s ‘05’ that had recently won Bathurst, PB’s sixth win at Mount Panorama.

It was very quiet at Lang Lang the day Barry Lake, photographer Warwick Kent and I arrived to test and photograph the hottest new Holden in Australia.

The huge test facility had been shut down for half a day to enable a no-holds-barred match between Peter Brock’s Bathurst-winning 05 car and his latest road-burning equivalent, the Group Three 5.0-litre Commodore SS.

The protagonists will be familiar to readers of MOTOR over recent issues. The construction and detail work that goes into an HDT Commodore racer was covered in the September 1982 issue. Since that time, of course, the SS model Commodore has been homologated, with the “big valve” engine producing more horsepower and torque.

The SS homologation also meant less weight, substantially improving the power-to-weight ratio of the cars. In essence, it’s a 5.0-litre Commodore SS with modifications too numerous to recall here.

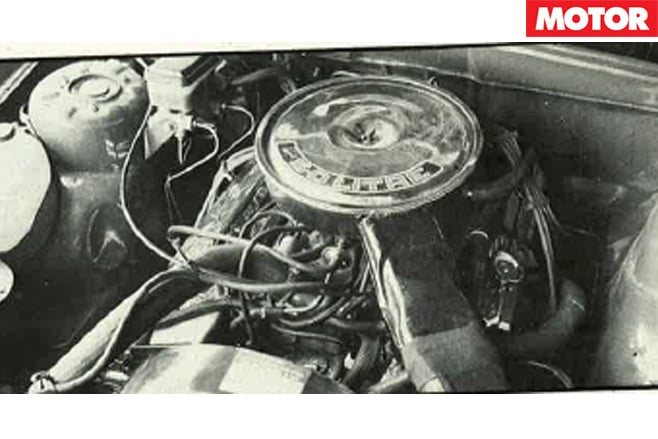

The engine in Brock’s Bathurst car, and still fitted at the time or our test, was an extra good one according to HDT engine builder Neill Burns. It produced 292.4kW at 6500rpm and 496.4Nm at 5000rpm. Drive is via a Borg & Beck triple-plate clutch to a Borg-Warner Super T- 10 four-speed transmission.

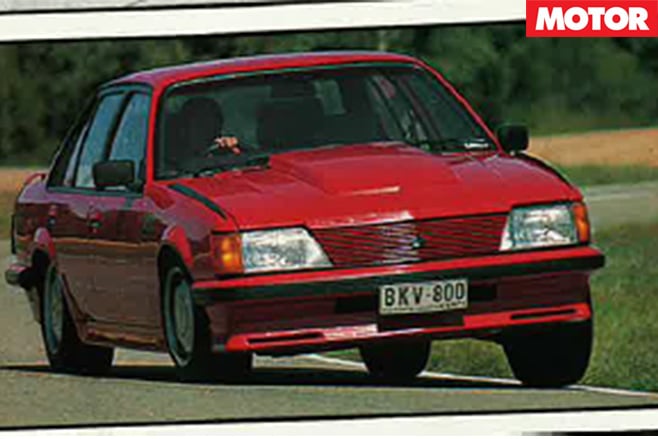

The road car is based on a four-speed manual 5.0-litre Commodore. lt comes from the factory with the “big valve” heads, the M21 gearbox used by Holden for all its performance specials since the XU-1 Torana, limited-slip differential and four-wheel disc brakes. The HDT Special Vehicles operation makes a number of mechanical and cosmetic changes, depending on the level of modification specified.

Group Three is the ultimate level of development. Front and rear springs are changed, shock absorbers are replaced with Bilstein units and new anti-roll bars go in front and rear. A new, harder rubber is used in the top mounting point for the front struts and the struts are turned around one post in their three-bolt pattern to increase steering caster and straight-line stability.

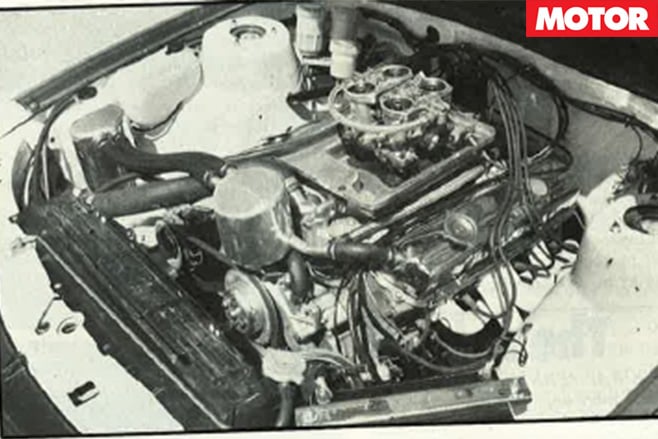

The three-quarter-inch brake master cylinder is replaced with a one-inch component. Engine modifications consist of ignition blueprinting, a cold air intake from just behind the grille to the air cleaner, exhaust extractors, chrome rocker covers and air cleaner and other detail changes.

These few change boost the 5.0-litre’s power output from 126kW at 4400rpm in standard form to a more respectable 184kW at 4750rpm and 418Nm of torque at 3500rpm. Maximum torque in the standard engine is 361Nm at 2800rpm. Maximum recommended engine speed goes up to 5500rpm although the redline stays at 5000rpm. The engine meets all current emission standards.

The wind splitters on the front guards are functional and are designed to route air cleanly over the bonnet and roof. The 5.0-litre four-speed with full Group Three modifications weighs in at around 1370 kg, giving it a weight-to-power ratio of 7.45kg/kW.

Flat on the banking

It’s cold out there in the Dandenongs first thing in the morning, but the temperature soon rises as the sun comes up. HDT mechanic Martyn Watt arrived soon with the 05 car in tow behind a trusty Holden ute that once sported an L34 engine, but that’s another story. Now it’s down to a 4.2-litre V8 and we followed Martyn as the 05 car was taken around to the 5km banked circuit and unloaded.

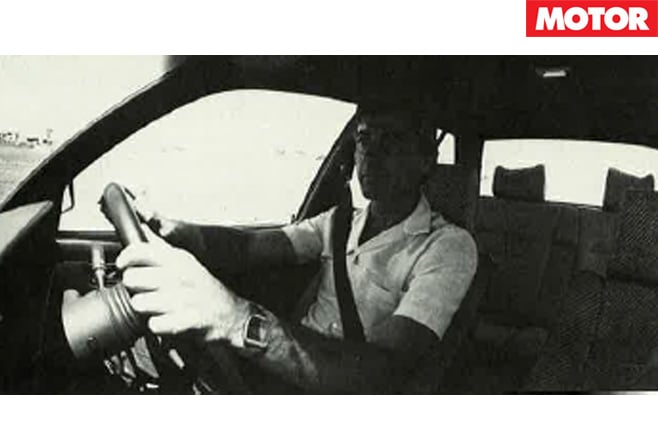

John Harvey, our test driver for the day, had arrived in the road car by now and got togged up in his racing suit as the racer was unloaded. Race cars don’t have chokes and I was invited to place my hands over the throats of the huge Weber carburettors as Martyn churned the car into life on the starter motor. A few coughs, splutters and the 5.0-litre racing engine bursts into life with an eardrum-tickling roar.

After a few laps we stop and Warwick hops into 05 with John to photograph him at work in the cockpit. This provides an ideal opportunity for Barry and myself to follow in the two road-going cars and run them out to their top speeds for our performance figures.

The next six laps are a celebration of speed. The 05 cars disappears into the distance, lost somewhere in our leftmost peripheral vision or out of sight on the other side of the track. Barry, 500 metres in front of me leaves the Alfetta on acceleration but cannot shake the Italian car in top speed as we circulate foot flat to the floor in top gear in the topmost groove of the banked track.

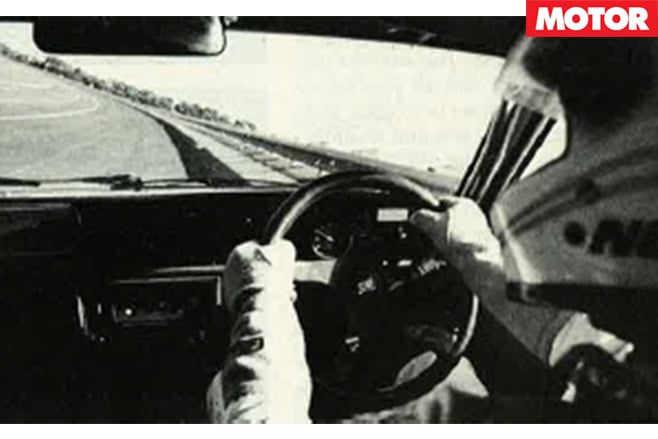

John Harvey stops. Warwick changes to the back seat, we pull in behind and start again. Once more 05 disappears in to the distance, the engine sounding more like a low-revving Formula One engine than a production-based pushrod V8. The sound is clean, hard and smooth. It seems to go on climbing forever in each gear until, suddenly, Harvey makes the upshift – fast, clean and with hardly any disturbance to the smooth blast of acceleration.

We learn minutes later that John Harvey (and Warwick) have seen 6600rpm in fourth gear – 265km/h or 165mph in the old measure. Our best was a mere 210km/h indicated (G3 SS) and 230km/ h indicated (Alfetta). Both corrected back to a more realistic 210km/h.

We move to the handling circuit where usually Camira and Commodore prototypes are driven around and around, day in, day out. Today it’s ours and we pick a corner for John and Barry to sweep through for our photographs.

Both must approach the corner at high speed over tram-tracks set in the road as part of the test circuit. Silence reigns, soon shattered by the beautiful induction/exhaust scream of the 05 car as John Harvey approaches nearly flat out in second.

The car whips through the corner, the only indication of the speed being the roar of tyres above the exhaust noise. Barry follows in the G3 SS. It turns into the corner particularly well, soon after crossing the tram-tracks. Its near-silent progress is only disturbed by the roar of the huge Uniroyal radials on the tarmac. The race car handles the turns with near-perfect neutral balance.

You may have noticed during the Bathurst telecast that Peter Brock does a lot of left-foot braking (short stabs on the brake pedal in corners to balance and neutralise the car). John has such faith in the car’s handling that he brakes very hard and turns at the same time immediately after our photo corner.

Barry likes the way the ultimate SS handles some understeer as speeds rise, but controllable either with power or a trailing throttle. The latter lets the car tighten its line. At low speeds more power will induce easily controllable oversteer.

I go for a quick ride with the fleet-footed Lake. The speedometer needle is soon hovering on 130-plus km/h as we negotiate the handling course. Along one longish straight we accelerate hard. Soon, too late, we see a couple of dips in the road.

The humps in this road are virtually invisible on approach, like many a similar hump on everyday roads. They are followed by ripple strips, designed to test the integrity of suspension bushes and NVH suppression. We hit these at about 130km/h and they pass almost unnoticed, the suspension again offering just the right combination of compliance and control for maximum adhesion.

Around the handling course the G3 SS is blindingly, deceptively quick. No drama, no squealing tyres, or dramatic transitions from understeer to oversteer, just fast, controllable handling that ranges from slight understeer to power-on neutrality. Fast, safe and reassuring for enthusiast drivers.

Faster and faster

We move to the brake road for acceleration tests. First 05, but myriad problems surface to upset the Correvit test equipment. The head (which attaches to the side of the car and bounces a light beam on the road to read speed and distance) is being shaken around by the car’s vibrations and won’t give an accurate reading.

We move it to the rear door on the passenger’s side. No joy. Then Lake the systematic finds the head IS reading the exhaust pulses at idle (the exhaust exits under the front passenger door). We relocate on the right rear door and then find that power surges from 05’s electrical system are upsetting the microprocessor that computes speed, distance and elapsed time.

We stop. The road curves down to the left a little. First gear. The clutch goes in. Wham! We’re off, the rear end drifting sideways under full power. It’s a fantastic start, but the clutch is playing up and John has trouble engaging second gear smoothly. Another blast of neck-jolting acceleration, then third gear and 400 metres have flashed by in 14-odd seconds. We have readouts and transfer the test equipment to the G3 SS. Barry drives.

This car is impressively quick, knocking over the 0-400 metres in 15.65 seconds with only a little wheelspin at the start. During the first run the car revs cleanly to 4700rpm and then suddenly dies. We lift the bonnet and soon discover the problem – a fuel filter too close to the exhaust extractors and the petrol inside it is boiling away merrily, causing vaporisation and a lack of fuel at high revs. This car was one of the first cars built and all production models since have the filter in a cooler spot.

Time was pressing by now and we didn’t have the chance to rerun the figures at Lang Lang. They weren’ t to the satisfaction of Peter Brock and he insisted that they be rerun, which we did at Melbourne International Raceway (Calder Park) the following Monday.

John Harvey in No. 25 beat Alan Grice in the Re-Car Commodore across the line in the following event with a time of 12.10 seconds. Grice, with sticky rubber and a lower differential ratio, recorded 11.74 seconds, but Harvey beat him to the line. This, we felt, was more like what could be expected of a top touring car. Peter Brock confirmed it – in person.

Brock did the driving himself. This time we did the road car first. Peter took the engine to about 4000rpm and dropped the clutch, while flooring the accelerator at the same time. First gear was all wheelspin, a snap change to second, then third and fourth briefly just before 400 metres flashes by.

The result? 14.90sec and 153km/h, and the engine still meets all emission requirements. The magic 160km/h came up in just over 16 seconds, which is better than all but the hottest early-1970s “supercars.” To put it bluntly, performance lives.

That magical scream again beside my left ear. The car rockets forward. With a triple-plate clutch in the race car his changes are only fractionally slower. Pit row is a blur, the 400 metres is gone and I drop my hand.

It’s taken us just 13 seconds to reach 176km/h in 400 metres with the “tall” Bathurst gearing and an engine with 1600km of hard racing behind it. Our test session is over. It’s taken us two days and many hours to get the performance of our hottest Holdens down on paper.

But it’s all been more than worthwhile. The closeness of the road car to the racing car has been underlined – the road car is only 1.9 seconds slower over the 0-400 metres test than the racing car, and all of this performance is usable thanks to the other changes to the car.

If ever the old motor racing adage “racing improves the breed” was true, it applies to these two cars. The Commodore SS racing car is amongst the quickest in Touring Car racing; its endurance is beyond question following the James Hardie 1000 and most of the lessons learnt by the team have been put into the road car.

All that is good news for the enthusiast and the motoring public appreciates such cars. When we visited Melbourne the special vehicles operation owned by Peter Brock had orders for 200 SS Commodores and was looking forward to producing another 500 in 1983 for sale through participating GM-H dealers.

Future fast

But that’s just the beginning. Brock and his crew of specialists have plans for even faster roads cars in the works at the moment. These will probably begin to appear towards the end of 1983. Ford must be regretting the day it decided to phase out the V8 engines from its line-up.

The Brock operation has shown just what can be done with the application of a little commonsense and racing know-how to sell a large number of high performance Commodores and give GM-H’s performance image the biggest boost it’s had in years.