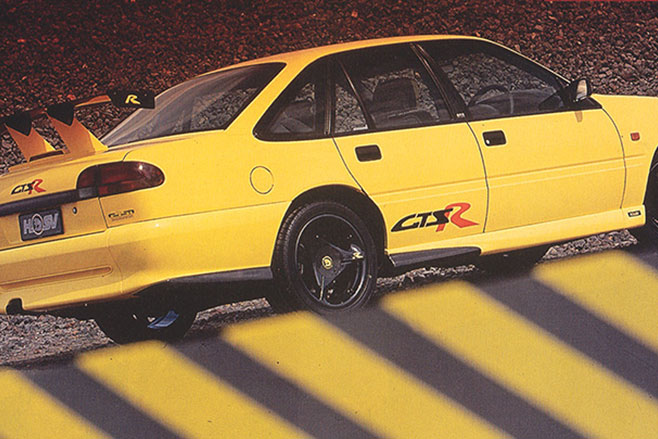

Ian Callum isn’t an easy man to pin down. After a number of attempts, I finally catch him as he waits for a guy to arrive and fix his washing machine. Unusually for Callum, he’s got time to kill, so what happened next is a rare privilege, one of the world’s premier car designers riffing at will on the state of the industry.Famous for designs such as theJaguar I-Pace, Aston Martin DB9, Nissan R390 GT1, Ford RS200 and, yes, parts of the 1996 HSV GTSR, Callum’s four decades in the business have cast a long shadow. That’s why when we were drawing up a shortlist of guest editors for the Wheels’ special Design, there was one name that kept being mentioned.

So here’s the full interview with Callum. It’s a big read, but if you ever wanted to get the fast-track on the design process and how it applies to modern cars, set yourself some time and dig in.

WHEELS: What are the key challenges in car design today?

CALLUM: Nobody really knows where the car industry is going to go at the moment. The whole industry, I wouldn’t say it’s in turmoil, but certainly it’s finding life very difficult because of the unknowns; because of the politics. There are two levels there. The politics are transient. The politicians need to understand the pains the car industry is going through in order to help it survive. It frustrates the hell out of me when you look at the ignorance of politicians around the world. They don’t understand the complexity and importance of the car industry and how it’s fundamental to not just our manufacturing society but our society itself.

I’ve worked 40 years in the business. It feels about four years. Let’s talk about the processes. I started out drawing cars with Ford, we were doing the Mk2 Escort. Cars were styled with magic marker, crayons, chalk, full-sized renderings on boards with ink and airbrush. All the artistry we learned was put to full use in order to communicate what we wanted this car to look like.

Fundamentally the big change for Ford came with the Mk3 Escort. It was forward transverse engine, and it was a marked change in both layout and possibly features and technology. Prior to that, cars were very much styled almost in isolation of what was happening beneath them. That was a throwback from American cars of the ’50s, where the body changed according to fashion each year and what was underneath was basically the same chassis.

Styling was about the shape of the car. We rendered these things up and made them look the way they did. We worked with the package engineers and we tried to make sure the lines we wanted fitted the engine below it. That was unnegotiable. If you want to set out the package of the car, you start out with the position of the cowl (x and y). That’s the pivotal point of any design and sets up the position of the engine. It was always suspected that the style of the car, like fashion, was very important. That choice still prevails. The car industry – through the Italians and Americans in the ’50s – recognised that style and design was very much part of the culture of the car world and were respected for it.

So as we move forward, that respect very much varied on who was running the business at the time; whether it was the CEO, the chief engineer (because design historically worked with engineering – it certainly did at Ford). It became more and more respected as people better understood the importance of branding; how a vehicle could look and tell the story of the car company it stood for.

The process stayed pretty much the same until the computer came along. What were sketches in magic marker became, if we skip forward a few years, renderings in Photoshop. Having said that, most designers still sketch. I still do it every day, even as a director. It’s the most expedient way of getting your ideas across to others. It’s a form of language in many ways. From that point on, the computer process took over.

From that we went on to 3D modelling quite quickly. Once we did full-time tape drawings in sections and that went to clay modellers who would cut the clay. What came out of that in the first few days was completely unknown until you got there and had to manipulate the clay to shape the car from your own mind, with the team of expert clay modellers. Now you digitise the car and render it up and you can see the car almost complete before you cut the clay. Every car company still works with clay. They might say that they don’t but nobody’s prepared to go straight from the digital world into manufacturing tools without seeing what they’re going to get. To cut a clay model is not a difficult thing to do these days, it’s just that the process to arrive there is different. Your choices are much more abundant.

It used to take me half a day to render a car, then the boss would say, “Can I have it in a different colour”, or “Can I have different tail lamps” and the only option was to start again and re-render it all. Now we can add three or four features in minutes. After the respect for design became greater in the business, designers got a lot more say in how the cars came about. It was no longer a case of ‘here’s a package, draw around it’. I suspect that some companies are still a bit like that, but certainly none that I’ve worked for.

In the TWR, Aston Martin and Jaguar days, we were given much more say in how this car should evolve. What does it stand for? What does it mean? We were part of the storytelling of the car, which became a very important part of the decision making as to whether the car is designed or not. Nowadays designers are acutely aware of the engineering that goes into the car, they’re aware of the marketing. The branding is very much part of their domain as much as it is marketing.

It’s a far more complicated job now. Before I left, I had Julian Thomson, who’s in charge of future strategy and design at Jaguar, and he works almost daily with the strategic departments deciding what should and shouldn’t be made. Those decisions are now part of the design department. And because they’re so passionate as designers, they push very hard to get what they think is right. The energy you see coming out of the design department for future product is huge.

A designer now is really someone whose view is quite holistic about what a motor car is. It’s not just stylists with pens and paper and that’s a fundamental difference, not just in the process, but in the need for design.

I will get challenged on this and perhaps you can make a case for the chief engineer or the vehicle line director, but there’s nobody else in the business who knows more about the car. Take any exterior or exterior part and ask them about the story of that part. Nobody knows the backstory of that part more intimately than the designer. They have to go through the whole process of making sure the design gets made the way they want it to be. And it’s not just a simple door card or a round headlight like it was in the Mk2 Escort. These parts are now incredibly complex. Pricing, weight, costing – the designers know these details intimately and they have to in order to protect their work or come up with alternative ideas. If you want to know about any component that you can see, feel or touch in a car, ask the designer.

That said, electrification of cars is making our jobs a little easier. Let’s consider exterior design. When we get back to the overall package of the car, the fulcrum of the car is the cowl height and position. That will set up the shape of the car. If you have an electric car, you suddenly have more freedom. In an ICE with an engine in the front, the cowl’s going to be the same height as the engine and that sets up the shape of the car. That’s why cars have ended up with a very similar profile for a number of years. The physics behind it, the geometry is all the same. With electrification, that freedom startsto open up.

Yet despite that, with electric cars we started out with something fundamentally simple and now there’s a demand for bigger inverters, bigger transformers, bigger electronic accessories, so that space in the front is now being used up almost by default with components the electric car needs. The dilemma the designer has is that he comes in and says, “I don’t want these components. I want to get the cowl height down.” Do that and you get the freedom to go cab forward and get the sightlines down so you get better visibility of the road. That’s all good stuff. But all too often, before you know where you are, somebody has set up this front package with all this stuff in it and you’re back to square one again. It’s a bit of a dilemma and the designers have to get in there early like we did with the Jaguar I-Pace. We needed to influence the height of that cowl. So it only gives you the freedom if you allow that freedom to happen. I look at some electric cars and you’d be hard-pushed to figure out whether they were electric or internal combustion. It’s a missed opportunity. Where you put a transformer is much more flexible than where you put a gearbox.

Design led: Porsche Taycan

I can think of some German electric cars like that. People say, well, that’s because they don’t want to frighten people off, by building it more conventional, but the fact is it’s because the front end is just full of stuff that could just about go anywhere. Whereas if you look at something like the new Porsche Taycan, that’s a car driven early by design. I’m sure the design department were there to protect the design as best they could.

The other frustration with electric cars – especially with sportier cars – is if you by default have got a skateboard platform, you inherently end up with about 125mm of height that you don’t necessarily want. If you’re dealing with SUVs or sedans you can learn to live with that. The offset of that is that you need to put different wheels on the car, to scale it differently. Of course, with SUVs you can do that quite readily. For some reason, the engineering and marketing teams accept that the wheels can be bigger on SUVs without question, whereas on a sports car it has more of a bearing in weight, but cost as well. The one challenge on an electric car is the skateboard platform in terms of height. When we go to a generation of pure sports cars, we need to find another way around that, and it could end up in a ‘mid-engined’ configuration for the batteries for that reason.

WHEELS: Do you feel there is a move back to more conservative rather than radical design?

CALLUM: It gets back to where the design team get involved in the make-up of the car. A lot of people feel that the whole strategy of a car, in terms of aesthetics and design, starts at the boardroom level and they see the design team asking for something more conservative or something more radical. I don’t see that really happening. I think what happens is there’s a domino effect that starts off and it’s a matter of trying to control those dominoes as they rattle off through the company.

“Okay, we’re gonna build a car. It’s going to be electric. Right, Design – get in there quickly and make sure you get what you want out of this. If you don’t get in there quick enough it’ll be too late and you’ll end up with the package that you’re given.” I have to say that the German brands are more prone to do that than we have been at Jaguar or Land Rover, and the net results are the results of circumstances rather than any conscious decisions to be conservative or otherwise.

I may be wrong in some areas of design. In Japan, they tend to go with more radical in some people’s eyes and wacky designs in order to get people’s attention – and I’m thinking Honda at this point. I don’t think it’s a conscious deliberation of whether something should be conservative in most instances, it’s just people trying to get the best out of what they’ve been given to work with.

WHEELS: What is it that excites you about the future of car design?

CALLUM: I reflect on this a lot. I feel a sense of huge challenge for younger designers now. Not only do they have to know what’s happening physically, in terms of geometry and engineering, but they need to be more politically astute in order to get that through the system. It’ll be difficult for them because the car industry is in a state of unknowing and that dissipates right down through the business. That offers up a state of confusion or a state of opportunity. The smarter designers will see the latter and that comes back to my point on how they can actually influence the future.

The first of many: Volkswagen’s ID.3 EV

I think electric cars are inevitable. There’s enough pressure on the ecology of the world to move this forward. The rate of change that it moves forward is causing the disruption in the car industry. If somebody said, “Every car you build in 10 years’ time will be electric”, it’d be a very queer decision but we’d know what to do. The thing is, we don’t know what to do. In 10 years’ time, will we build internal-combustion engines? Will they be diesel, hybrid or hydrogen? The world is struggling to understand what to do.

There’s a state of opportunity, where the design team need to become crystal ball gazers and make some fundamental choices. It’s betting the farm. Volkswagen has been quite clear about this as a result of their Dieselgate fiasco. They’re going to go electric big time. Is that the right choice or is it an overreaction? Truth is, we don’t know.

It’s a gamble but it’s a PR gamble, holistically too. It offsets some of the damage it caused to their PR. I don’t know if it’s the right decision. I like to think that it is because I’m a great believer in these sorts of products. I don’t know if the world’s ready for it but the world needs it. But can the infrastructure cope with it?

WHEELS: Is design an increasingly important aspect in the process?

Absolutely. The aesthetic of the car is very important. There are two parts to this. One is because the inputs – I had a discussion with a BMW designer about this – their inputs are much more rigid than those at Jaguar. They get set dimensions to work with. They work these dimensions. The profile of the car, the shape of the car is dependent on the input that they get based on people package, aerodynamics, cost etc. We get the same inputs because the world is the same, people are the same, physics are the same, but what we do at Jaguar is we challenge these inputs for the sake of shape and style. Fact. We do. We want a better looking car. Of course, you can then say, “Okay, it’s a better looking car, but what does it offer?” Well, it offers a better looking car. That to me, and the buying public, is still important. What the car looks like is still very important to the consumer. In the niche market that is Jaguar, we depend on that difference. The BMWs and Mercedes of this world don’t have to do it as much as Jaguar.

It’s also important from the perspective of designers having an influence on what the car should look like in the first place. The whole notion of I-Pace was dreamt up through some very innovative engineers and the design team. We decided that we were going to have a cab-forward car with a short bonnet. This didn’t come out of some marketing research or some diktat from the top of the business. This was what designers wanted and this was the opportunity we had to do it. If they can understand what’s happening inside the car, how the company works and how the car is built up, designers have a much greater opportunity now to go and influence that.

The other point is that designers also understand the idea of the motor car better than anyone else in the business. And when I say the idea, I mean they understand the product holistically in terms of enthusiasm, its place in the world and its artistry better than anyone else in the business.

You won’t print this, but I’m sure you’d rather go for a drink with a bunch of designers than product planners wouldn’t you? If you take a business nowadays that’s based on historic fact, designers don’t base their lives on historic fact, they base their lives on the future. That’s why design is so important, because they look to the future rather than the past. You have to learn from the past of course.

The other great challenge with electric cars is the mass of the car. Although the I-Pace defies its weight and feels quite an agile car, it is over two tonnes, and that’s something we feel very uneasy about. That’s the nature of the beast. Because of that, the crash requirements then become that much more demanding. It means that the crash structure at the front can become larger and larger and that takes away the opportunities you might have had with a less heavy car. Lighter batteries are something that you might have to push hard for.

WHEELS: What’s in your immediate future now that you’ve left Jaguar?

CALLUM: I’m working on a small project to begin with. Ultimately, of course, I would like to do a car – not saying that I’m going to, because that’s going to be in the realm of who can help do it. I certainly can’t afford it, but I like to think that we can get involved in the greater parts of car design on a bespoke and individual basis. I don’t really want to go in and do mass-produced cars for the foreseeable future. Again, I’ve done that over 40 years and I’d rather just focus on stuff that may be a little indulgent, but I like to think I’ve earned it.

I want to focus on the artistry of the car now; enjoying the aesthetics and the design of it in a much purer form, and the only way to do that is perhaps through a limited-edition vehicle, albeit they’re probably going to be quite expensive. That’s what I’d like to do. Not just cars, either. I want to look at other things too. Once you can design a motor car – and product designers might not agree with me on this- but once you’ve been through designing most aspects of a car, you can probably turn your hand to most things. Including boats, interiors, architecture, watches…

WHEELS: Do you see a role for yourself mentoring younger designers?

CALLUM: Yes, I would like that. The thing is, my experience will become less valid. The car industry is moving so fast, that even in five years I might not be able to recognise it. I would like to take the opportunity to guide people in the right way. The one aspect I had at Jaguar as Chief Designer was as a catalyst. Young guys would try something and I’d say, “Don’t bother doing that. It’s not going to work.” They might persist, and the next time they’d listen to me a bit more readily. That was always the humorous part of how we worked. One of my associates would say, “Well, I don’t think Ian’s going to like that” and I’d come in and say, “I don’t like that.” And I don’t like it because I know it’s not going to work. It was never a case of suppressing ideas, I just figured that instead of going down a blind alley, I might as well tell them now rather than later.

WHEELS: What’s changing in the process of car design right now?

CALLUM: Designers need to be more holistic, there’s no doubt about that. They need to use this opportunity of change to make it happen: to suit what they feel to be correct in terms of the motor car. Autonomous driver is going to take on a completely different stand. There’s a slightly negative view in terms of design. Maybe it’s a more democratic view that the motor car will suddenly become this mobile box. I call it ‘anonymous autonomous’ where the design of the box is very much about function and the aesthetic doesn’t matter. I don’t believe that should be the case. I think anything that has to be designed has to be designed properly. I also believe that no matter how autonomous the world becomes, there will always be people out there, particularly in the luxury market, who want their object of transportation to be a bit more desirable, a bit more exotic and a bit more luxurious than everything else.

There’ll always be a place in this world for drop-dead sexy design, Callum believes

I think people will always want something special, no matter how different the process of using it might be. If you’re renting, hiring or whatever, I still feel people will still want to get into objects of desire. And that gets right back to branding. Otherwise we’d just all have fairly bland watches on our wrists, wouldn’t we?

WHEELS: Are car buyers more design literate these days?

CALLUM: Oh yes, absolutely. And that varies. They’re very design literate, but whether their taste is in keeping with where I think their taste should be or where other people think their taste should be is another matter. What might be bad taste to me is acceptable to somebody else. What’s important is that they’re very much aware of what they’re doing, what they’re seeing and what they’re doing and how they’re portraying themselves. They see motor cars or transportation as an extension of their own character. When people put their clothes on, they’re very aware of what they’re wearing.

I remember one person saying to me, “I’m not interested in the design of what I drive.” I said, “Really, what do you drive?” And he said, “I drive a Volvo.” Well there you go, you’ve made your statement. That statement to drive a Volvo is a very deliberate one. There was a time when Volvo was less exotic than they are now. It was an explicit statement of “I don’t really care what I’m driving.” A statement of non-statement is still a statement.

I think most people around the world – especially in emerging markets – are becoming hugely design literate. They know what they want and that goes right through everything they buy. They have choice like never before.

The Chinese market will have a huge influence on the rest of the world. I see a very positive effect on the young Chinese design fraternity in building their own aesthetic. That’s more based on the traditional Chinese design ethic of simplicity and purity. That’s their history. They’ll influence things over and above the visibility of wealth. A sense of good aesthetic will come through.

Super size me: the 1976 Cadillac Coupe deVille illustrates Ameicans’ love of big cars

These emerging markets develop their own design maturity. We’ve seen that process happen in Japan. Theirs, for instance, is a culture of detail. There’s no space to stand back and look at anything. You laugh but it’s true. You can’t stand back 300 metres to look at a car you’re designing because there just isn’t the space to do so. That’s why American cars and Australian cars became so big. Geography has a huge effect but mass global digitalisation will have a bigger one.

WHEELS: We don’t have too much good news about Australian manufacturing…

CALLUM: The loss of the Australian car industry is a crying shame. I worked in Australia and did a lot of work in Melbourne. It’s such a great place to be. I think my brother Murray’s insisting on keeping the Ford design studio there, so I’m glad to see that. They won’t go away. You guys need a car industry back again. The population’s big enough to justify it. The world’s a poorer place without a Holden or a ford ute with a thumping great V8 in it.

The Design Issue of Wheels is on sale now in all reputable outlets and online at magshop.com.au