THE CONTADINO who owned the fields adjoining the Lamborghini factory must feel like a lottery winner. His ship’s come in.

First published in the June 2017 edition of Wheels Magazine, Australia’s most experienced and most trusted car magazine since 1953.

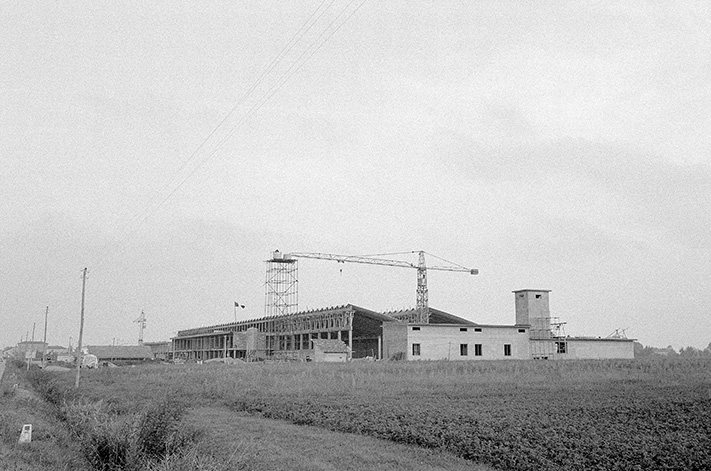

For decades, the factory that Ferruccio Lamborghini built in 1963 was big enough to knock out two or three hundred cars a year. But since Audi bought Automobili Lamborghini SpA in 1998 and poured in money and resources, production has rocketed to last year’s record 3457 cars. The Urus SUV coming in 2018 should double that. And where, in the grim days before Audi, there were 300 employees, now there are 1415, and Urus will need another 500.

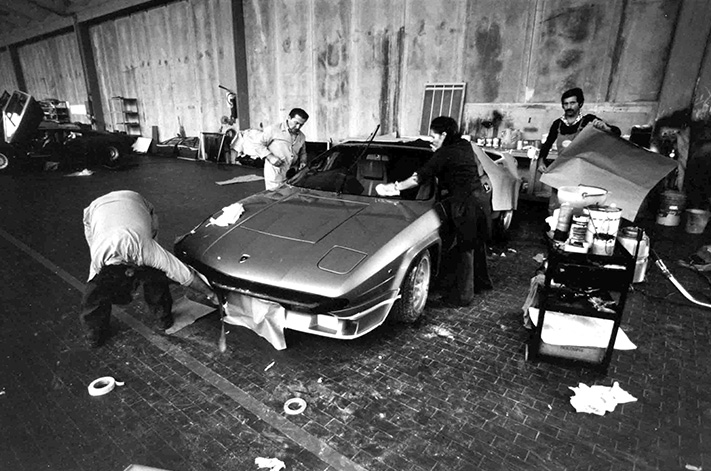

These days, the plant at 12 via Modena, Sant’Agata Bolognese, on the Emilian plain 17km east of Modena and 24km north-west of Bologna, looks familiar albeit bigger and smarter. The long Lamborghini script still stretches along its roof. But the facade of the old offices and main entrance fronting the production hall has been freshened and abuts the new museum’s long, high, glass gallery. In the 1970s, when I came here often to drive the latest and greatest, the only old Lamborghinis were customers’ cars in for service and forlorn-looking prototypes and mules dumped out the back.

Back then, you might have encountered a couple of suppliers coming and going, or the odd owner bringing a car in for attention. Nowadays, scores of visitors – 65,000 a year – mill about outside the museum, waiting to ogle five decades of Lamborghinis and tour the factory.

Sant’Agata’s composites prowess dates back to 1983, not long after McLaren introduced carbonfibre to Formula 1. Then-boss Giulio Alfieri commissioned a composites project to see how much weight might be cut from a Countach. Fortune smiled: aeronautics engineer Rosario Vizzini, who’d been at Boeing in Seattle designing the 767’s carbonfibre vertical stabilizers, had just returned to Italy. Lamborghini snapped him up and got an injection of cutting edge composites knowledge. Vizzini’s project was the carbonfibre frame and body of the Countach Evoluzione. It was 500kg lighter but too expensive to build. Steadily, though, more and more composites became part of Lamborghinis.

Does Lamborghini’s commitment to composites square with the Volkswagen Group’s desire for increased platform sharing? “We work closely with group marques but if a technical solution becomes too much of a compromise it’s not a solution.”

“The Huracan is a good example of one that worked. We are trying to conceive a common platform for another sports car but can’t say yet whether it will be successful because there are so many differences between the brands. My opinion is that, on a super sports car, having a platform that’s good for everybody will always be a compromise.”

“We have one important mother,” Reggiani says. “She has allowed us to make this huge investment, achieve the results we’re now enjoying, and create a dream like the Urus in a short time.”

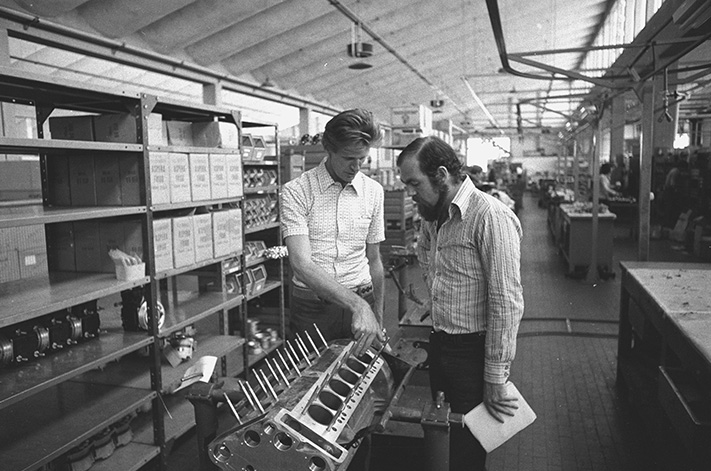

Reggiani, an engine man who came to Sant’Agata in 1994 after six years at Maserati and six at Bugatti, has links to Lamborghini’s engineering roots: he has worked with Paolo Stanzani and Gian Paolo Dallara, Lamborghini’s founding engineering giants. He points to a treasured photograph signed by Dallara, Stanzani and designer Marcello Gandini. “These three, as young men, built the original dreams of Lamborghini,” he says. “Dallara and Stanzani were innovators; visionaries who understood what Lamborghini stood for. They wanted to make the purest incarnation of a super sports car. Bob Wallace understood how to translate the sensation of driving a sports car on the road, and communicate that back to the R&D team.”

Mindful of his legacy, Reggiani is driving Lamborghini full-tilt into a tech-dense, scientifically analysed supercar position that includes aeronautical technology for chassis control, four-wheel steering that works up to 200mph and simulates shrinking or stretching the wheelbase, sensors embedded in tyre rubber, revolutionary aerodynamics, and neurological research into how drivers react.

Yes, but some testers thought the original Huracan understeered too much. Reggiani says: “My immediate response is: what mode are you in? In Strada, which is biased towards understeer, if you’re not a great driver you will have great safety because you can enter bends without the rear moving too much. In Sport, we assume your skill is better so we give you more tail movement by adjusting front-to-rear torque. In Corsa, you have neutrality for optimum speed through a corner.” Nevertheless, he confirms that Lamborghini did mildly revise the front-to-rear torque calibration for the Huracan Spyder to make it more neutral in Strada.

Now there’s the four-wheel steering standard on this year’s Aventador S. At low speed, the rear wheels turn in the opposite direction from the fronts to virtually shorten the wheelbase and boost manoeuvrability. At speed, the rear wheels turn in parallel with the fronts. “It’s like elongating the wheelbase by 500mm,” says Reggiani. “It gives us great stability at high speed.”

The Aventador S’s more sophisticated and dramatic nose – which generates 130 percent more downforce – rear panels, wing and diffuser are aerodynamically focused to increase stability across a wide speed range. Lamborghini has learned a lot from working with Dallara on its Huracan Super Trofeo and GT3 race cars. The Huracan Performante’s ingenious ALA active aerodynamic system is a direct practical application of this work. “Venturi effect is really important,” Reggiani says. “It’s the only thing that increases downforce without penalising driveability. Aerodynamics and weight are the two pillars where we will push to innovate as much as possible.”

Lamborghini is also continuing the research program with the neurology faculty of Rome’s Sapienza University that began during the Huracan’s development. It’s to learn more about drivers’ reactions. The scientists discovered that, in emergencies, the right side of the brain manages the left hand. So the Huracan’s turn indicators and headlight flashers are tabs on the left of the wheel where they can be worked with your left thumb. “This kind of analysis helps us be more scientific about control layout.”

What about engines? In a world moving to smaller turbocharged units, and electrification, Lamborghini’s smallest engine is a 5.2-litre V10. “Our job is to continue to be flag-bearers for the naturally aspirated V12 and V10,” says Reggiani. “New rules governing sound, fuel consumption and emissions, and taxation, will kill today’s big naturally aspirated engines. When that happens, the big task is to ensure that what comes next has the same emotion and performance.”

A year after launch, the petrol V8 (Reggiani makes it clear that diesels aren’t on Lamborghini’s agenda) will be joined by a hybrid, important not only for the SUV but to lower the fleet average for emissions and consumption. Hybrids for the sports cars are another matter. Although the 2014 669kW Asterion plug-in hybrid concept showed how Lamborghini can include electric power, and it has all the Volkswagen Group’s knowledge and systems to draw upon, resistance to adding 250kg or so means Sant’Agata will hold off introducing hybrid sports cars in volume until battery weights decrease and range increases. The V12 will continue until the end of the Aventador’s production life in 2022 “and possibly beyond” according to Reggiani.

His exuberance sums up the atmosphere at Sant’Agata now. While, for most of Lamborghini’s 54-year history, brilliant engineers and dedicated employees somehow, often against the odds, kept Ferruccio Lamborghini’s vision alive, they never enjoyed this kind of confidence, and this kind of capability. Stephan Winkelmann, through his 11-year stint as CEO, guided the company to this place of new dreams, and left it in rude health when he handed over to Stefano Domenicali: ex-Ferrari, locally educated and steeped in the automotive culture of Emilia-Romagna.

You get the feeling that having an Italian in charge again is the icing on the cake.