“If you know there’s change coming,” says Jochen Hermann, “you had better prepare for the change.” And that’s exactly what AMG’s new chief technical officer is doing.

Appointed to the position a little over a year ago, Hermann spent 2016 to 2020 as head of electric drive development for Mercedes-Benz’s parent company Daimler. In that role he was intimately involved in the creation of the company’s first purpose-designed EV platform, known as MEA (for modular electric architecture) and the stunningly efficient EQS that’s the first car to be based on it.

Now Hermann is tasked with engineering a future for AMG in a time where the bottled lightning of battery packs will gradually replace the thunder of the brand’s revered V8s. The time is coming when the AMG’s appeal will depend more on cell chemistries than cam profiles, and he’s is excited by the challenge.

Hermann studied aerospace engineering, and worked for a time in the sector in the US before remembering his childhood dreams and heading back to Germany to join Daimler in 1997. “When I was a young kid I read all these car magazines, so I made a decision [to leave] aerospace because I wanted to build cars.”

Our kind of executive, then…

I meet Hermann in a conference room above the Mercedes-Benz stand at the recent IAA Mobility expo in Munich. Below us two new electrified AMGs are appearing in public for the first time.

Hermann is tasked with the future for AMG. The time is coming when the AMG’s appeal will depend more on cell chemistries than cam profiles, and he is excited by the challenge

One of them is the battery-powered EQS53. This large luxury liftback has acceleration to beat almost any internal-combustion AMG ever made, so why doesn’t it deserve to be called EQS63?

“That was a discussion,” Hermann admits, “Saying, okay, is it a 53 or 63? For me it’s quite clear it’s a 53.” The reason? Anything called 63 has to be track capable, as he sees it. And the EQS53 isn’t…

“With the electric car, the easiest thing you can do is accelerate, but it’s still not a performance car from my perspective. Considering this, I’m not sure if a 63 will be based on this car…”

But does this also mean none of the coming models based on Mercedes-Benz’s purpose-designed MEA platform, including the EQE, will be 63-worthy? “You don’t hear me arguing with this statement…”

So what has to change for AMG to be able to create something worthy of the 63 badge? “I jump to the GT 4-door car,” Hermann begins, referring to the 63S E-Performance plug-in hybrid, the most powerful AMG ever produced, also on show in Munich. “That describes, I think, the future technical approach that we will see.”

“If you take a Mercedes plug-in hybrid and you look at the battery technology, the KPI [key performance indicator] the team was focusing on was energy density. So; gaining as many kilometres of electric range out of this battery, and still having enough space in the car for [ample] luggage in your boot.”

“With the GT 4-door E Performance car, we decided we don’t care about the electric range of driving for this performance hybrid,” he says emphatically.

The AMG’s official electric driving range is a paltry 12km from a small 6kWh battery. But the pack can contribute 150kW to the car’s total power output for up to 10 seconds, or 70kW continuously, via an electric motor mounted on the rear axle.

“We came up with a battery with the most efficient power density,” says Hermann. “It’s energy versus power.”

The distinction is an important one. As Hermann points out: “If you look at the technical build-up of the battery, it starts with the cell technology.”

Prioritising battery pack power density does have benefits. Because they can charge as quickly as they put it out, they’re able to cope with massive power from regenerative braking

Energy density is a measure of kWh per unit of battery pack volume. More kWh equals longer driving range, but the kind of cell chemistries that deliver superior energy density aren’t able to deliver sustained high power outputs.

Power density, on the other hand, is a measure of kW per unit of battery pack volume. In other words, the ability to supply power-hungry, high-output electric motors with what they need. The trade-off is inferior energy density, again a consequence of basic cell chemistry.

But prioritising battery pack power density does have benefits. Because they can accept charge as quickly as they put it out, they’re able to cope with massive power inputs from regenerative braking. Even more important, they can do the same when charging from the grid.

Hermann thinks power-dense battery packs are the logical choice for future electric AMGs. “In a performance driving situation, like using maximum power – because you want to accelerate all the time and [therefore] need to brake all the time and recuperate all the energy – if you install this into the car, the one thing you get for free is fast charging.”

“I’m not a believer in building the largest batteries into cars,” Hermann says. He believes it’ll take time, but all types of EV owners will come to understand how much driving range they really need on a daily basis. “People will learn from experience.”

So, as range-anxiety fades, the focus will shift to recharging rates, Hermann predicts: “I think fast charging would be something people would love to have in an AMG.”

Does that mean battery packs that can take advantage of the latest generation of 350kW fast chargers? “At the moment that’s the limit; what you have on a European Ionity fast-charging station. But why not more in the future?”

What this means is the potential for electric AMGs with recharge times to rival fossil-fuel burners.

What AMG won’t do is strive to compete on driving range. The Mercedes-EQ 450+, for example, is good for a WLTP-rated 780km. Around 500km will be enough to satisfy AMG EV customers, Hermann believes.

“I think you have to have a certain threshold for range; a comfort level that customers accept. Okay, this is the minimum range you would want to see in a car, no matter how performance-oriented the car is. So yes, I do think there’s a threshold that [we] can’t go beneath.”

What AMG won’t do is strive on driving range. Around 500km will be enough to satisfy AMG EV customers, Hermann believes

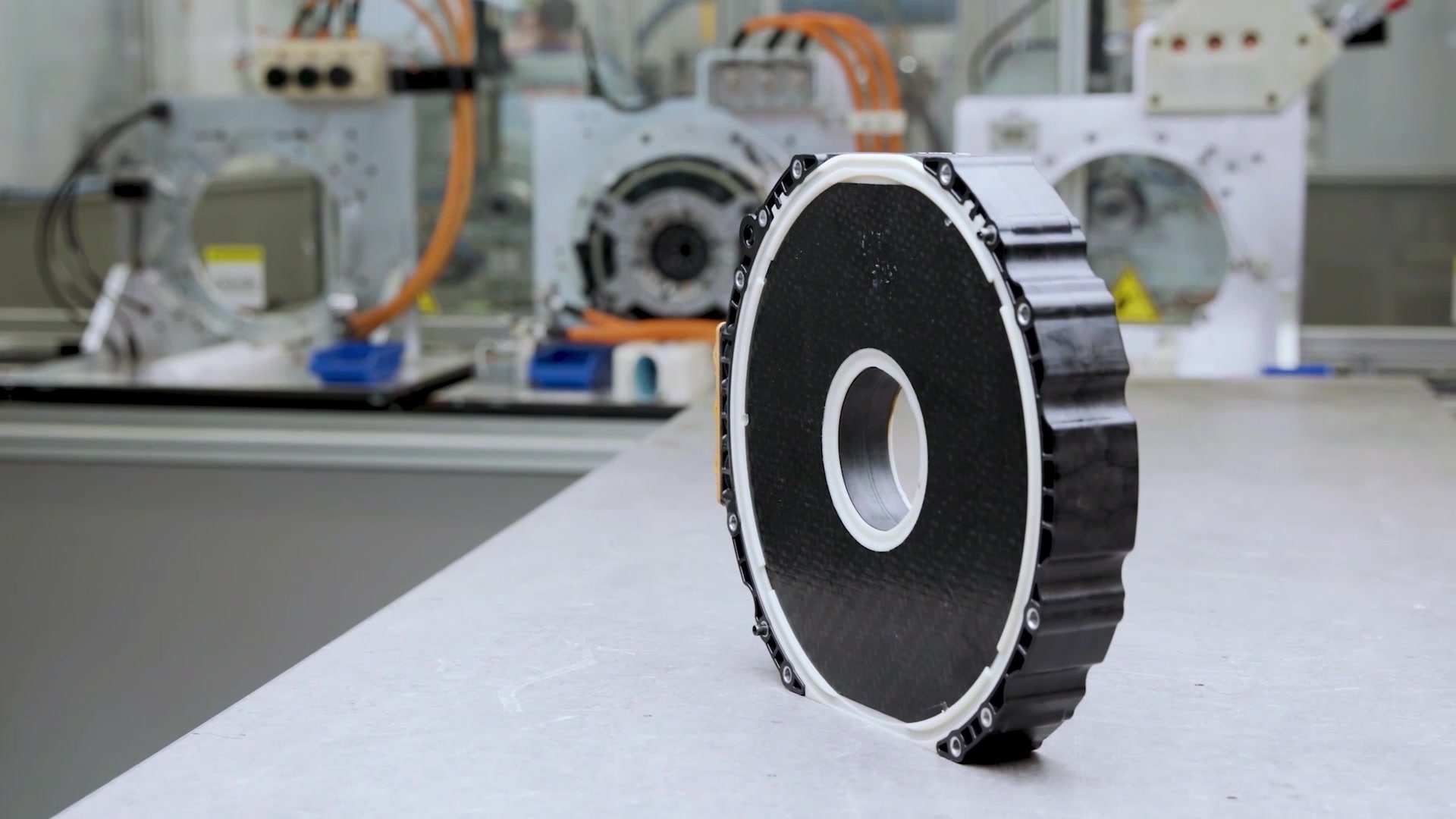

The other area where AMG is looking for an EV-era advantage is electric motor technology. “We bought a company called Yasa a few weeks ago,” Hermann says “Another company [Daimler] bought it for us, but AMG was the driver. This is the technology that would really be something valid for an AMG performance car.”

Before the Daimler deal was inked, UK-based outfit Yasa was practically unknown. It gained a little attention as the manufacturer of one of the three electric motors in the Ferrari SF90 Stradale, but that was it.

Founded in 2009, Yasa grew out of research by a bright student of Oxford University. Now employing round 250 people, it has a small factory on the outskirts of the city. The company’s specialty is axial-flux motors. They’re unlike the radial-flux motors currently used in pretty much all EVs.

To visualise the difference, think fast food. Imagine the fast-spinning rotor at the heart of an electric motor is the meat in your meal, and the stationary stator is some crusty or bready flour-based product. In this case a radial-flux motor is like a sausage roll, where as an axial-flux motor is more of a burger in a bun, tipped on its side.

Hermann sees tasty potential in axial-flux motors. They offer packaging advantages compared to radial-flux motors, he says. Though he evades a direct answer when asked if their shape makes them especially well-suited to in-wheel installations, he does hint that Yasa motors are an integral part of the plan for the new high-performance EV architecture under development at Affalterbach.

Hermann sees tasty potential in axial-flux motors. They offer packaging advantages compared to radial-flux motors

Known as AMG.EA, it’s one of the three new EV architectures announced by Daimler chairman and Mercedes-Benz boss Ola Källenius in July this year and due to appear from 2025. The others are MB.EA for medium and large mainstream Mercedes passenger products and Van.EA for light commercial vehicles.

AMG.EA will serve as the basis for the electric successors to the cars currently built on AMG-specific platforms – the GT and GT 4-door. As it does today, AMG will also produce Mercedes-based models in the electric age. “Both pasts will be put into the future,” is the way Hermann puts it. “And the AMG.EA will definitely be for the path for future full AMG cars only.”

And Hermann understands that the electric AMGs of the future must excite. “Driving a car, emotionally; it’s a holistic experience,” he says.“Even in an electric car you have to give something to your eyes, like something happening in front of you while doing a race start. Rattling. Shaking. Even sound. Not an artificial V8 sound, but something underlying and experienced through all your senses: ears, eyes, hands, your back, your chest; every part of you that’s connected to the car.

“These are the senses we will use for making an electric driving experience close to what people know today. Of course, today when they say sound, actually what they mean is a V8 or a high-performance four-cylinder. Once this is gone, you have to come up with something. I think sound will be something still important for AMG…

“I’m not really nervous about the future. I think the pure DNA of AMG – like vehicle dynamics, the software, the aerodynamics, the tyres, the brakes; all these things that make a perfect car – this [stands to] play an even more important role in this new electric drivetrain era.”

Even so, Hermann doesn’t foresee AMG’s thunder road being turned into a pedestrian precinct any time soon. “Looking into the next 20 years for a V8, how many years do we have? I think quite a few…”

But the end is definitely coming, he acknowledges. “Is everything solid forever? No! Nothing is, you know. Everything can change.”

Project One and Only

Project Two? No way. “I can tell you 100 percent Mercedes will never do another street-legal Formula One car,” says Jochen Hermann.

The AMG chief tech officer admits the company bit off more than it could chew with Project One.

“Seriously speaking, this is the most complex powertrain anybody can think of. I hate myself. I can remember the meeting room when the idea came up. You know, when ideas come up, and you have a bunch of crazy people, you never talk about the downsides, right?”

“I’m really excited that we did the car, because it really pushed us as a company. I also think it pushed us as a brand. We learned so much, and I think it’s a technological historical object.”

“And, yeah, apologies to all our customers…”

The Cooling Guys

The power-dense pack of the new GT 4-door 63S E-Performance plug-in hybrid doesn’t only point to AMG’s favoured future strategy for EV batteries, it also taps into established Affalterbach expertise.

The pack’s 560 F1-derived cylindrical battery cells are bathed in a special non-conductive coolant that’s pumped through a heat exchanger. This pack’s power density would be much reduced without this innovation, so far unseen in other plug-in hybrids and EVs.

The five AMG engineers who developed the pack are also responsible for the company’s combustion engine cooling systems. To Jochen Hermann the jobs are almost identical: “If you look at the battery housing, I mean, what is it? It’s cooling; a tight housing with seals and liquids.”