SERIOUSLY, after all this time, you’d think there’d be no more barn finds left to find. With the classic car market frothing like champagne in a blender, surely there isn’t an unopened shed left in the world. Everyone’s dream is to lift a rusty garage door and discover your elderly aunt has been hiding a long-lost Facel Vega, once owned by Elvis. In 2018, aren’t we at least a decade too late for all that?

Well, the stories keep coming: in 2016 a Lamborghini Miura was dragged out of a tiny back-street garage in the US, covered in dust, after nearly 20 years in hibernation. In 2017, Steve McQueen’s Bullitt Mustang, no less, turned up in a Mexican scrapyard after being lost for nearly 50 years.

And now this car. Not just any old Land Rover. Not just one of a handful of super-collectable pre-production cars. This is the actual launch car from the 1948 Amsterdam motor show, where the Land Rover was first revealed to the world, 70 years ago. An incredibly important car that until recently was abandoned in a back garden about five kays from where it was built in Solihull, England.

In some ways this story is even more remarkable than those of barn-find Lamborghinis and long-lost Ferraris. Not because of value but because Land Rovers are for nerds, obsessives and trainspotters. The early Series 1s have got to be among the most energetically researched and documented cars of all time: chassis numbers are catalogued, archives are trawled, former engineers are tracked down, dragged out of old people’s homes and pumped for information. No one escapes the Series 1 Inquisition! So how could the Amsterdam show car disappear for so long?

To answer that, we need to go back to the beginning – and if you’ve heard this story a thousand times, feel free to skip a couple of paragraphs…

The Land Rover story begins in 1947 in Anglesey. Maurice Wilks, the technical director of Rover, owns a farm there, where he uses a demobbed army Jeep as a farm hack. Raw materials are scarce in post-war Britain, and the government is only supporting firms that can export the nation out of its knee-high financial manure. Wilks knows that, as a luxury car maker, Rover isn’t going to be building luxury cars any time soon, so he has an idea: how about an agricultural vehicle, a lightweight car-tractor? A British Jeep, in other words, that improves on his old farm hack?

So, using another ex-army Jeep as a guinea pig, Wilks develops a single, crude prototype with a Rover P3 engine and gearbox, three seats and a steering wheel in the middle (which at the time seemed like a good idea for exports, but proved to be a terrible idea for legroom).

Moving with suitable we’re-all-about-to-go-bust post-war haste, Rover quickly progresses from that single proof-of-concept to the pre-production stage: 50 chassis, of which 48 are built up into completed cars, all numbered 01, 02, 03 etc, prefixed with either an R or an L depending on whether it was right-hand or left-hand drive (the centre-steer idea was dropped as soon as someone tried to drive it).

The remains of those 48 pre-prod cars are now holy relics to the Land Rover fraternity. Mike Bishop, Land Rover Classic’s Series 1 expert, tells me around 20 pre-prod cars have survived. “There are a couple where literally a buff logbook is all that’s left,” he says, “but at least we know when their lives finished. Of the complete cars, they rarely come up for sale – R12 sold about eight years ago, but it wasn’t really public. They tend to sell from one collector to another.”

I ask him how much they go for. “I’m probably not the best person to answer that, because I own R16!” Bishop admits. “But it’s easy to speculate it would be in six figures nowadays for a pre-production Land Rover.”

The most famous of the early cars is the first, chassis R01, known as ‘Huey’ after its number plate, HUE 166. Huey’s a celebrity – the final, limited-edition Defender Heritage models in 2015 all had HUE graphics. Huey was built in March 1948, and he was saved for posterity by Maurice Wilks himself. “In 1949, Huey was put to use on a farm near the Wilks’ home near Kenilworth,” explains Bishop. “It was there until 1955, when Wilks rescued it and put it in the Birmingham Science Museum. It was used for Land Rover’s 10th birthday celebrations in 1958, when it was placed on a massive cake. It’s now owned by the British Motor Museum.”

Just six chassis after Huey, Rover built the car you’re looking at now. Susan Tonks takes up the story – Susan’s an engineer who has been with Jaguar Land Rover for 18 years, the last six months of which has been with Land Rover Classic, and she’s now this car’s restoration project leader. “It was originally left-hand drive, so the chassis was stamped L07,” she explains. “It left the factory on 27 April 1948, and was driven to Amsterdam in time for the car’s official unveiling on the 30th.”

Ha! Anyone who’s driven a Series 1 Land Rover for three kays will guffaw at the idea of this car, canvas flapping and gearbox droning, driving nearly 500km to the Netherlands.

“They put chassis L05 on the stand, inside the show itself,’ continues Tonks. “This car was the driving demonstrator, used outside by the press.”

Of course, we know how well the show went – Rover’s post-war, stop-gap model became a gigantic success, and a global brand in its own right. But between the launch in April and the first cars going into production in July, there was still a lot of work to do. “After the launch, L07 went to Rover’s engine department, where parts were changed, tested and upgraded to production spec,” Tonks explains. “We believe this is when it was converted to right-hand drive, and you can see on the chassis where they stamped an R over the L to make it R07.”

It stayed at Solihull until June 1955, when it was sold to its first private owner, but here’s where its importance as the 1948 show car begins to get lost in the fog. On the dispatch note it’s recorded as E07, presumably because it was the Experimental Department that built the pre-prod cars. Also, its first registration number – SNX 910 – never showed up in Rover’s own records, because it was registered by its new owner the day after he’d bought it.

So, like a rare Roman coin slipped into your pocket, R07 disappeared into all that loose change on Britain’s roads, and was lost. The original logbook (which miraculously still exists) shows the car was sold on to new owners in Sutton Coldfield, then Stratford-upon-Avon, before ending up in Wales in 1968. It was parked in a field and used as a static power source for 20 years, its power take-off running a farmer’s wood saw. Twenty years of sitting out in the rain and the frost, overgrown by nettles and inhabited by wildlife, until eventually the engine seized and its working life was over.

In 1988 it was sold to a collector of early Land Rovers who – ironically – lived just five kilometres from the Land Rover factory, back in Solihull. This enthusiast knew the car was special, possibly a prototype, but didn’t realise its full significance. So the car stayed in his garden, awaiting a restoration that never came, until 2016, when he decided to clear it out. By then the car was up to its axles in mud, and it had to be jacked up before it could be hauled out of its shallow grave. Through a network of tip-offs, news of the car reached Land Rover Classic, who bought it for an undisclosed sum.

It’s worth noting Mike Bishop already knew the significance of the car before it was found: “From documentation and photographs, we knew the only cars that were built and available to go to Amsterdam were chassis 01 to 08, and we knew they were left-hand drive, which means they were odd numbers [apart from Huey, right-hand-drive chassis were evens]. By a process of elimination, we knew the missing L07 was one of them.

“Other early cars had been traced though old MOT records, that kind of thing,” explains Bishop. “But 7 was one of the few pre-prod cars we didn’t have the registration for, so we had no knowledge of what had happened to it. For it then to just appear, out of the woodwork, was fantastic. I was at home late one evening and a friend of mine who’s a Land Rover historian rang up and said, “You’re never going to believe this, I’ve got someone who’s got chassis number 7!” He sent me a photo and as soon as I saw it, I knew; I could tell by the pre-production features. I went to have a look at it about a week later, and confirmed it – we’d found the missing number 7.”

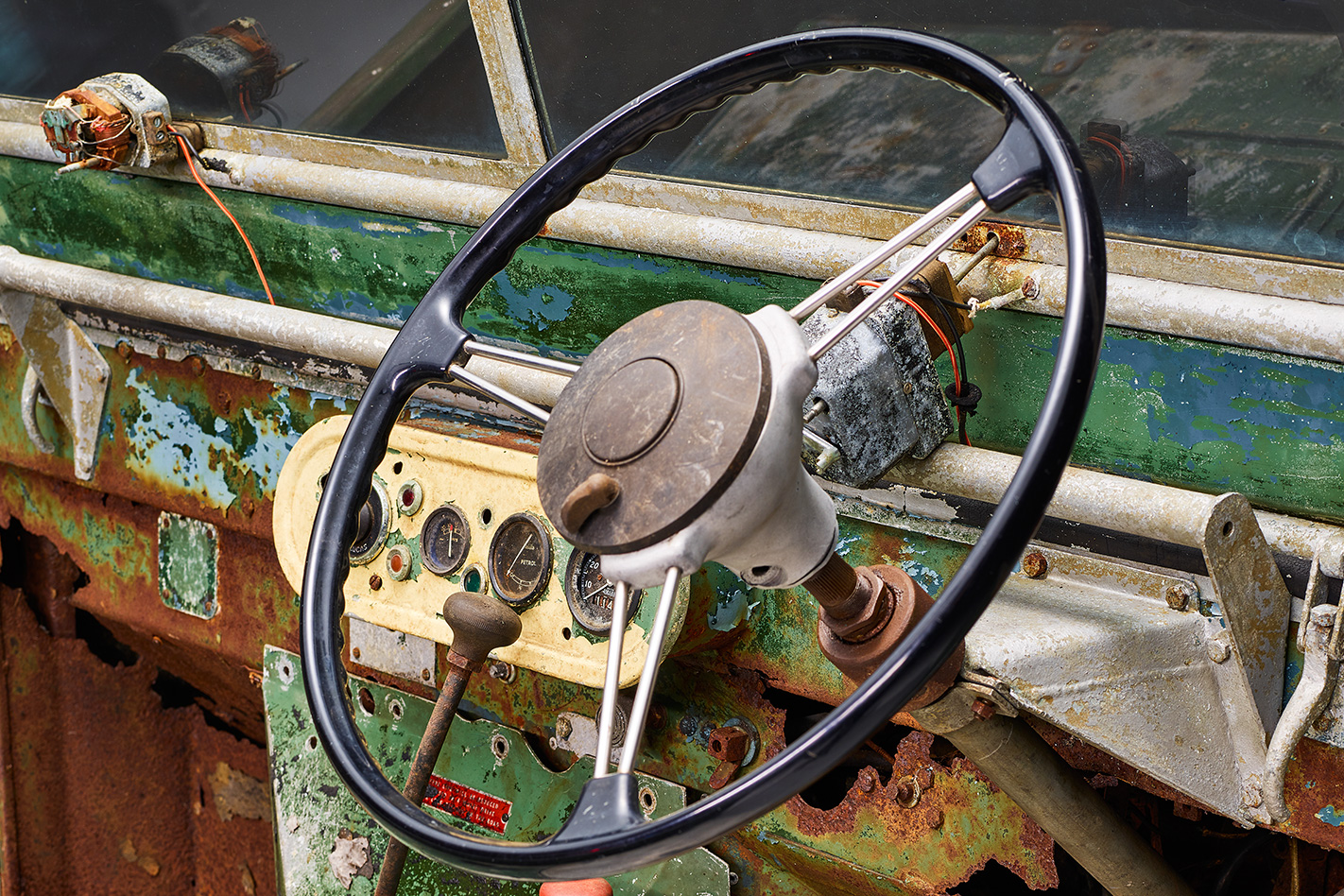

Hand on heart, I cannot claim that an audience with the 1948 Amsterdam show Land Rover is like being in the presence of a Mille Miglia-winning Maserati or an ex-Senna McLaren. If you didn’t know any better, you’d think you were looking at scrap.

But if I could get poetic for a moment (cue rousing music) there’s something beautiful in the scars and scrapes, a nobility in its flaking paint and sagging suspension, the hallmarks of a life lived to the full. It’s called patina and it’s worth a fortune. The paint is like some kind of Jackson Pollock, a random mosaic of three distinct colours, with an alloy base-layer beneath. “The light green is the original paint from the Amsterdam show,” explains Susan Tonks. “It was then painted dark green, and at some point in its life it was painted blue.”

Most of the panels are original, and just by tapping you can hear the thicker alloy in the outer wings and the one, surviving pre-prod door. “The curves on the front guards are slightly different too – they were obviously trying things out on the pre-production cars,” says Tonks.

The rear tub is also prototype, though the rear lights are later additions; the tailgate is pre-production with a lot more reinforcement than the final spec. The bonnet, windscreen and axles are all original. The engine is seized, but it too is original, stamped number 6. The brakes were an experimental Lockheed system, later converted to production-spec Girling. The plan is to re-make the Lockheed system from scratch using archived drawings. Amazingly, the steering wheel is original too, its Bakelite proudly polished up by the Classic team. How on earth did that brittle plastic survive 70 years of neglect and hardship? There are so many details that make you shake your head in wonder. “It’s undoubtedly the most original survivor of all the pre-production cars,” says Tonks.

Most amazing of all, though, is the condition of the steel chassis. Hand-made back in 1948, it was galvanised, unlike the later production cars that were painted (galvanising was dropped for mass production because of the finishing required, drilling the zinc out of all the blocked-up bolt holes). Climbing under the car for a closer look, the chassis is amazingly solid given it spent the best part of four decades planted in the ground like a carrot: here and there you can still see the silvery galvanised finish; elsewhere there’s a white, salty looking crust, but no rust and no ragged holes.

That can’t be said of the bulkhead, the vertical steel wall between the engine bay and the cabin. This is the weak spot of all Series 1s, so much so they’re re-manufactured and galvanised nowadays, for restorers. This car wasn’t so lucky – again, it’s clearly handmade and crudely formed compared to later production cars, and it was painted. The weather has ravaged the steel, and there are big holes in the footwells.

Of course, it can be fixed – cut out the rust and weld in the new – but the bulkhead question goes straight to the heart of the challenge facing the Land Rover Classic team: how far should they go to restore this car? Should it be rebuilt at all? And if so, to which spec? Left-hand-drive Amsterdam? Or Welsh farmer sawmill? The bulkhead is key: there are lots of early Series 1s coming over from Australia these days with a lovely patina. But it looks really odd if the faded panels are left but the rusting bulkhead is restored to a glossy, greeny newness. Patina is as fragile as a snowflake – touch it and it melts away.

“It definitely won’t be a Reborn car,” says Tonks, referring to Land Rover Classic’s factory-fresh Series 1 program. “The idea is to preserve the patina – though to return it to a proper, functioning condition we do need to decide, what do we replace or repair? Do we repair then ‘age’ the bulkhead, so it looks in keeping with the rest of the car?”

Whichever way the team decides to go, the plan is for the car to take centre stage in Land Rover’s 70th anniversary celebrations this spring, and then it’ll be painstakingly dismantled, documented to death and rebuilt within 12 months (somehow).

But if you think that’s the last one, don’t worry. The other car at the Amsterdam show in 1948, chassis L05, has also never been found – it might still be out there, sitting in a field or a garden, up to its axles. Even more intriguingly, the whereabouts of the original centre-steer prototype has never been conclusively pinned down either. Was it torn apart, or turned back into a Jeep and sold, or did Maurice Wilks save it and park it somewhere?

I’ve decided to go to Anglesey this weekend, to start opening barn doors.