Take an exotic engine, bung it in a bread-and-butter car and, for some reason, you’ve usually got yourself a classic set of wheels.

It doesn’t work in reverse, of course; who’d want a Gallardo with a Daewoo engine, for instance? Still, there’s no getting away from the appeal of a Brand X body with a D&G powerplant.

Need proof? Okay, take a 7.0-litre Corvette engine and stick it in a Commodore. Then call it a W427 and wait for the internerd forum kiddies to canonise the thing. Vauxhall has done it (the Lotus Carlton), Citroen did it back in the ’70s (the Maserati V6-powered SM) and, in the mid-’80s, Ford pulled off one of the best by slinging a Cosworth lump into a rep-racer to create the Bathurst-winning – make that everything-winning – Sierra RS500.

Management approached Lotus boss, Colin Chapman, with the idea of Lotus building 1000 homologation specials and Chapman, who knew a good deal when he saw it, agreed, even though he was also in the process of finalising the production of his own Elan. It must have been a busy time in the Lotus workshop.

Why did Ford choose Lotus? Well, obviously, Chapman had a few runs on the board. But the arrangement was for the development of the Lotus twin-cam engine to also be part of the deal.

By 1962, Ford had the five-main-bearing Kent on line. With its capacity of 1.5 litres (1499cc, although the car pictured here is the later 1558cc) with Mundy’s double-overhead-camshaft head in place, it cranked out an astounding (for the time) 78kW – Chapman would have called it 105 horsepower.

And don’t forget that a standard Cortina didn’t have carpets or a radio and even the E-Type Jag didn’t get a glovebox lid as standard in those days, so a twin-cam engine was real news.

The mods to the front were pretty predictable, with shorter struts and forged (rather than pressed-steel) track arms. But out back, the changes were much bigger. The standard Cortina live axle suspended by leaf springs was flung in a skip and an A-frame cradle sprung by coils and upright dampers slotted in.

That dictated some strengthening ribs and braces in the boot and the rear-seat bulkhead, standing the spare tyre upright. While they were at it, the engineers also moved the battery to the boot to improve weight distribution.

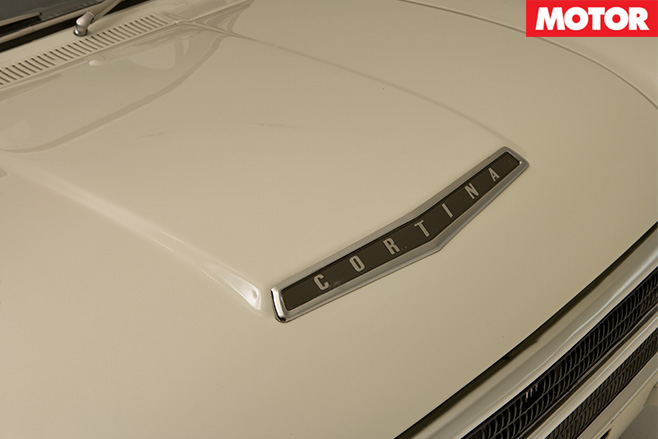

Body-wise, you had front quarter-bumpers, Lotus badges and a white-with-green-stripe colour scheme (though Ford built a few red cars for racing). But, more importantly, the boot, bonnet and doors were pressed from aluminium to keep weight down.

Inside, the Elan gearbox dictated a centre console to allow for the different shifter location and you got racy seats and a full suite of gauges so you could tell precisely when the engine was about to explode.

Timing chains wore out quickly and, if you’re shopping for one, listen carefully for timing-chain rattle, particularly when the engine is hot. Watch out for a timing-chain adjuster that’s screwed in as far as it’ll go, too, as that indicates chain and guide wear.

The rear suspension also proved fragile, with many competition cars requiring constant attention to keep their rears tracking properly and the diffs off the ground. The other big problem surrounded the gearbox ratios.

To be honest, a ‘normal’ Cortina GT was a vastly better day-to-day road car. But that ignores the fact that the Lotus Cortina was a real legend and a giant-killer into the bargain. It might have been flawed as a road car, but as its racing history becomes more fully appreciated and its collectability assured, the smart money says get in now if you want one.

Apart from those durability and reliability issues we mentioned, the big catch is finding a Lotus Cortina that isn’t what it purports to be. Since the bodyshell was common as muck (and plenty have survived) and the Lotus twin-cam was ultimately used in all sorts of different models, there are still punters out there who reckon the idea of taking one and bolting it into the other, painting a green stripe down the side and tripling their money is a great plan. Ringers, we’re talking about.

THE GOOD

1. Bona-fide heritage It’s a 24-carat collectible with bonafide heritage in a world where too many second-tier cars are riding the investment financial rollercoaster.

2. Barrel of laughs A good example will still be rewarding to drive. It won’t be the fastest thing on the block any more, but it should still be fit enough to make you giggle on the right day.

3. Monkey business Provided you can find somebody who knows their way around the engine, keeping a Lotus Cortina in fine fettle shouldn’t be as taxing as it would be for many exotics.

THE BAD

1. Ka-pow! Could often be pinless grenades for no good reason. The engines weren’t the only demon, either – the rear suspension was also a problem child until a fix job in 1965.

2. Fine Cotton Don’t even think about forking out gold on a Lotus Cortina until the car in question has been verified by a proper expert. Be wary of advertised race history, too.

3. Only for Sundays Attempt to use a Lotus Cortina every day and you’ll wind up hating the thing for its hopeless gearbox ratios, fragility and race-car manners. It’s no grocery-getter.

Escort service

Even before the Lotus-bred Mk II Cortina and its touring-car aspirations went the way of the dodo. Ford decided to shove the Lotus 1558cc DOHC 8-valve four (and much of Cortina’s running gear) into the newer, lighter Mk I Escort. The Escort Twin Cam was born. Developed by Ford UK’s motorsport department and unveiled to the public in January 1968 as a limited homologation special, the Twin Cam had twice the power (82kW) of the basic Escort 1100, and formed the basis of a highly successful era of rallying for the marque. In June 1971, it was replaced by a Cosworth-tuned 16-valve RS1600 model.

The Lotus Cortina was a pretty handy race car … when it hung together. The first 1000 homologation cars were completed in September 1963 and that same month a pair of Lotus Cortinas finished third and fourth at a touring-car race at Oulton Park in Britain. They finished behind a pair of V8 Ford Galaxies but, significantly, in front of a pair of 3.8-litre Jaguars, which had been the dominant force up until then.

In 1964, the great Jim Clark was British Saloon Car Champion thanks to a Lotus Cortina and the little buggers are still a force to be reckoned with in historic racing.

The car’s highest ever recorded speed was a stunning 236km/h (147mph) down Conrod Straight at Bathurst with Marc Ducquet at the wheel.

In rallying, the Lotus Cortina should have done better than it eventually did. On tarmac stages it was sometimes all but unbeatable, but on gravel and other harsh conditions it displayed infamous fragility.

The first works rally win didn’t come until December 1965 when Roger Clark and Graham Robson won the Welsh International. By then, the troublesome A-frame rear end had been replaced.