ON REFLECTION, it’s been a lot like Star Trek.

Mazda began building its rotary engine 55 years ago, and for the past 40 of those the relatively small Japanese maker has gone boldly where no one has gone before.

Its reward has been a screechingly powerful and jet-smooth little rotor-motor with a character unlike any other, and a galaxy of loyal enthusiasts.

The recent news that Mazda continued to develop the rotary, even beyond the expiration of the RX-8 in 2012, gives hope that this adventure is far from over.

On a glorious day at Mine, a racing circuit turned test track folded in the mountains near Hiroshima, Mazda gathered many of its rotary heroes. Only a few were off-limits.

IT WAS real Captain Kirk stuff when, in 1960, Mazda president Tsuneji Matsuda flew to Germany to meet with car and motorcycle maker NSU.

There, backyard inventor Felix Wankel was developing a revolutionary engine he had first patented in 1929.

Rotary-piston pumps and compressors had been around since the 16th century, but Wankel was the first to apply the principle to an internal-combustion engine.

Mazda was the first but far from the only carmaker interested in this technology. Ultimately, no fewer than 11, ranging from Alfa Romeo to Rolls-Royce, would sign licence agreements with NSU-Wankel.

On Matsuda’s mind was his company’s survival.

Mazda, a small maker of three-wheeled trucks, had launched its first four-wheeled car (the R360) that same year. It had big ambitions, but Japan’s Ministry of Trade and Industry had plans to consolidate the country’s 10 automotive manufacturers into three groups. Mazda would be merged with Nissan and Toyota.

Matsuda believed the rotary would give his company a unique technology, a case for keeping Mazda independent. The strategy worked, and MITI’s approval in early 1961 to develop the rotary also freed Mazda to develop future passenger models.

In 1957, Mazda had 4500 employees, producing 41,500 three-wheel trucks. By 1967, it had 21,000 employees producing more than 400,000 vehicles, including five passenger cars.

Disturbingly, they saw 250cc single-rotor engines seizing on the test bed. They observed combustion chambers scored with ‘chatter marks’.

The problem lay in the apex seals, the metal scraper-blades at each tip of the triangular piston. Softer metals provided good sealing, but wore out in less than 200 hours. Harder materials created the ruinous chatter marks. That was as far as NSU had progressed.

Mazda held some unexpected aces in having a highly advanced toolmaking and measuring-equipment division, and wide-ranging skills in casting, materials and chemical technology, dating from its days as a wine-cork producer.

Then there was engineer Kenichi Yamamoto, later to become company president and forever known as the foster-father of the rotary.

In April 1963, the already 18-year Mazda veteran was appointed manager of a dedicated rotary research division. It’s said Yamamoto wasn’t entirely convinced of the rotary’s viability, but was quick to acknowledge it had enjoyed only a fraction of the attention devoted to piston engines.

Yamamoto and his ‘47 samurai’ found that the chatter problem emanated from resonance within the seal itself.

They tried internal cross-drilling, a sliding corner-piece, new materials in aluminium and carbon, a tensioning-spring system. They hard-chrome-plated the inner rotor housing.

Equipped in 1964 with a new lab of 30 test cells, new-fangled computers and a new proving ground at Miyoshi, Yamamoto’s team also figured a fix for the rotary’s moving-target ignition puzzle, by fitting twin spark plugs.

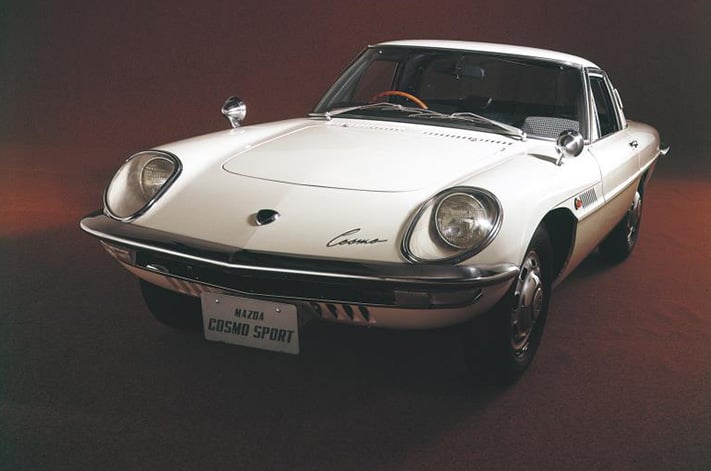

Later that year, Mazda built a pair of dramatically styled prototype coupes. Company boss Matsuda personally drove one from Hiroshima to the Tokyo Motor Show 850km away. The production version of this low-slung, dart-shaped Cosmo Sports coupe would take another three years – after comprehensive testing of 80 prototypes, 60 of them in customer hands.

AMONG the cars on hand at Mine are half a dozen privately owned Cosmo Sports 110Ss.

But the Cosmos’ owners, from a local car club, have a different style about them. It’s a feeling of confidence, simplicity and celebration that’s noticeable in everyone mingling here in the crisp, mountain air.

The Cosmo’s compact but adequately roomy cockpit sings of the 1960s, with a wood-rimmed Nardi steering wheel framing a central tacho redlined at 7000rpm. The little 10A engine is so light, crisp and linear in its delivery that it feels more like a spring-wound or turbine-driven device. I can only imagine how far-out this car must have seemed in the ’60s.

With my butt planted on the low-backed buckets, visually perfect in black vinyl with houndstooth inserts, I have just a finger-width of headroom. The steering wheel almost rests on my thighs and, despite a narrow transmission tunnel, the pedals are inexplicably offset to the right. And yet, magically, one is neither stooped nor cooped in the Cosmo; it fits and feels like a Hawaiian shirt.

To prove the revolutionary coupe’s durability, in 1968 Mazda entered a pair of Cosmo Sports in the brutal Nurburgring 84-Hour endurance race – that’s right, three and a half days. One retired with a broken axle, but the other finished fourth outright, 12 laps down on the winning works Porsche 911E.

The 10A was a twin-rotor unit of 982cc. It initially developed 81kW at 7000rpm and was upgraded to 94kW at the Cosmo’s first facelift. A detuned 10A, with 74kW, was fitted to Mazda’s first mainstream rotary model, the R100 coupe in 1968.

My adolescent exposure to rotaries was exploding right about then, too, as RX-2 Capella sedans and coupes began infesting my parents’ car club events. Launched in 1970, the RX-2’s 12A engine had been created by widening the housings by 10mm each (making 1146cc).

On track, Capellas were a match for Torana GTR XU-1s.

I found it odd that the pretty little RX-3 coupe of 1972 didn’t displace the more restrained-looking RX-2 from car club competitors’ affections. Fact was, Aussie RX-3s initially arrived with the 10A, and even the 12A-equipped facelift in ’74 was still slower than an RX-2.

Pretty much everything had come together with the RX-4 – aggressive styling, performance, handling, comfort and reliability – which explains why so many are still alive and loved.

Sadly, not for me at Mine, where the RX-2, 3 and 4 are infuriatingly offered only on static display.

By 1973, 80 percent of Mazda’s US sales were of RX rotary models. But the oil crisis in October put a spotlight on the rotary’s fuel consumption. Relatively thirsty against similar-sized (but less powerful) four-cylinder models, the Mazdas were labelled as ‘gas guzzlers’. Within months, sales tanked by 40 percent – while dull, four-pot Japanese rivals made hay.

Everyone but Mazda abandoned the rotary. With the death of the perennially troubled NSU Ro80 in 1977, Mazda was left to go it alone. And that’s the thing I can sense here at Mine. It’s as though everyone here has that feeling of lightness and gratitude that comes from having fought through near-death and come out the other side.

Mazda had done so by developing some conventional models, the smash-hit 323 and 626 of 1977-78. More importantly, it initiated the Phoenix Plan, with a target of reducing the rotary’s fuel consumption by 40 percent within two years.

The Roadpacer was meant to provide American-sized luxury within Japan’s strict engine-tax structure. It has more memorably provided decades of derision and automotive-trivia entertainment. Mazda has one in its factory museum, but declined to bust it out for Mine.

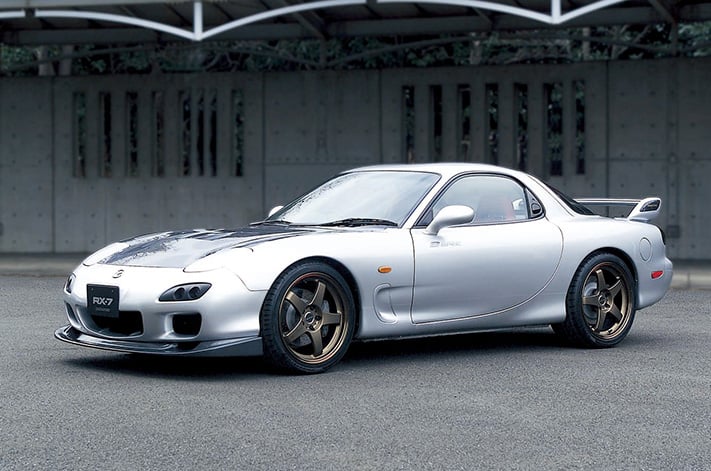

THE full fruit of Mazda’s Phoenix Plan appeared in March 1978, in the unforgettable shape of SA22C – the RX-7. It was a worthy successor to the lightweight performance coupe that had introduced the rotary engine 11 years earlier.

The relationship is surprisingly obvious as I slip behind the thin steering wheel – vinyl-rimmed this time, framing an 8000rpm-redline tacho – of a Series 3 RX-7. The absence of power steering is a brisk wake-up into Turn One, as are the possibly original tyres, but very evident is the same combination of linear power delivery and light chassis.

Everyone raves about rotary revs. In practice, the atmo rotaries are so smooth and audibly unfazed there’s barely any impression of approaching redline until the (very necessary) warning buzzer goes off.

The RX-7 had a similar profile in Australia through Allan Moffat’s campaigns from 1981-84. The car was always controversial, sparking fear and wonder around the emerging technology of its peripheral-ported 12A (and later 13B) engine.

These were all stepping stones towards Le Mans. A Tokyo dealer-entered long-tail RX-7 252i failed to qualify in 1979, but that was merely the first step on a 12-year path to the rotary’s red-letter year at the French classic.

If the second-generation RX-7 of 1985-91 looked like a Porsche 944, it went even harder – especially when optioned with the 146kW twin-scroll turbo 13B. The chassis was more sophisticated than the live-axled Series 1, with an independent rear-end featuring passive toe-control.

The RX-7 Series 6 (1991-2002) eclipsed its predecessor even more easily. These cars are still justifiably sought-after today with their smooth styling and sizzling twin-turbo performance. The early versions were a handful, with on/off boost, flighty steering and a nervous, over-sprung chassis. As I’m happily reminded at Mine, the later facelift smoothed those rough edges.

The funny thing is how the car’s increasing weight and sophistication was countered by the addition of twin turbos – leaving the distinctive rotary stamp of compactness, lightness and agility. The biggest thematic difference between this and the early Cosmo is the RX-7’s very black and quite claustrophobic cockpit.

An example I drove at Mine shouted at the still-untapped potential of the rotary.

The rotary’s supposed swansong was the RX-8 of 2003-12. Quite aside from the refinement of its Renesis 13B MSP (multi side-port) atmo engine, which met US emissions regs and boasted a 9000rpm redline, the COTY-winning four-seat coupe brought real innovation in the form of rear-hinged half-doors and lightweight, mixed-material construction.

Mazda had a pretty good idea of the Hydrogen RE’s performance; an engineer is installed for my test lap. “You see? You can switch from hydrogen to petrol power on the move, like this,” he explains as we drive out of the pitlane. And back again? “Unfortunately, you can only do that when stopped…”

WE ALL feared that the rotary engine went down with the RX-8. But as one Mazda man at Mine reveals: “It has never really been a successful business case. We haven’t had scale economy, even in the past. We have no textbooks, no teachers, nobody to compare with. But it has a value well beyond a business value.”

In the pantheon of automotive genius, only Mazda knows how to give the rotary life.