V8 or straight-six? For your German muscle car fix it’s not as clear cut as it seems.

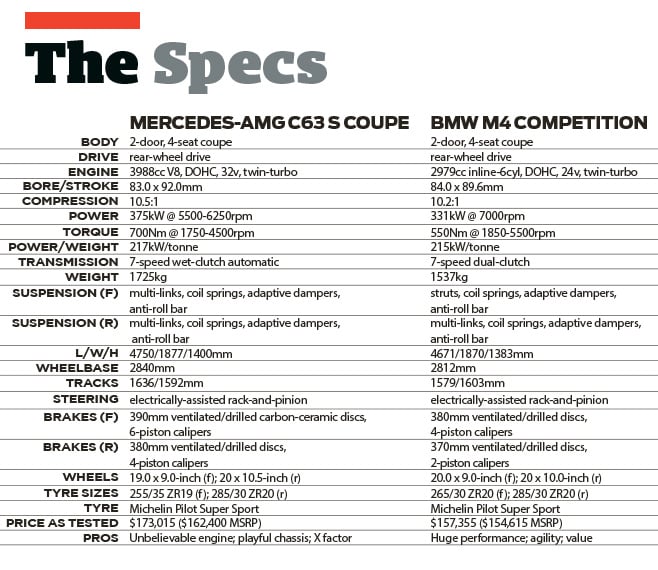

Details. It’s supposedly where the devil resides, and it’s certainly where the differences between the BMW M4 Competition and Mercedes-AMG C63 Coupe S lie. What we have here are two four-seat, rear-drive coupes at the top of their respective games.

Both are extremely exciting, capable and desirable machines, and though they occupy slightly different vocal ranges, both are singing from largely the same hymn sheet.

But this is no primary school sports carnival where everyone wins a prize – there are no participation awards here. You want to know who makes the best high-end Euro sports coupe, so let’s find out.

This allowed the front track to be stretched 20mm and the rear 50mm, as well as the fitment of wider wheels and tyres. Aussie C63 Coupes wear sexy staggered rims from the forthcoming AMG GT R as standard, measuring 19 x 9.0 inches front and 20 x 10.5 inches rear (sedan: 19 x 8.5; 19 x 9.5). These are wrapped in Michelin Pilot Super Sport rubber, 255/35 ZR19 (front) and 285/30 ZR20 (rear), 10 and 20mm wider respectively than the sedan.

Some of this is due to its reinforced bodyshell, but the wider, stronger multi-link rear suspension must also shoulder some of the blame. AMG went all-out on the rear-end of the C63 Coupe, with uniball joints replacing rubber bushings for sharper response, stiffer lateral arms to increase traction and a shorter final drive ratio for better acceleration.

The M4 and M3, on the other hand, are much more closely related. Identical under the skin, the M4 is 23kg lighter and shorter by 7mm in length and 41mm in height, which slightly improves its centre of gravity, but not by enough to make a noticeable difference. What do make a difference are the Competition upgrades, recently introduced as a new model in the M3 and M4 range.

In our experience thus far the changes have done a good job of taming some of the M4’s wayward behaviour without unduly hurting its day-to-day usability.

The M4 Competition’s biggest visual change is the adoption of new 20-inch wheels, the ‘666’ design nicked from the hardcore GTS, albeit without the staggered sizing (GTS wears 19s at the front) and thankfully sans the garish orange colouring.

We’re not so sure about the C63 Coupe. The front end is great, all ridges and bulges, and the overall shape has plenty of presence, but though the widened rear end is much more muscular than the narrow, upright derriere of the regular C-Class Coupe, it looks a bit saggy and lacks definition, like it’s eaten too much KFC.

No such qualms inside. Depending on what you’ve stepped out of, the seat may feel a little high and the backrest only just goes upright enough, but overall the driving position is very good, the materials justify the price tag and there’s even a decent amount of room in the rear, though taller adults will struggle for headroom.

In contrast, BMW’s once-maligned iDrive is a piece of cake to use. The M4’s interior lacks the glitz of the AMG but there’s leather galore and lashings of carbonfibre, the driving position is lower and more widely adjustable and there’s easily room for two adults in the rear. Forget two-plus-two, this is a genuine four-seater.

Possibly the biggest threat to the M4 Competition’s liveability is its ride quality. This is a very firm car; BMW states the Competition’s damper tune is roughly equivalent to Sport in the standard M4. Personally, it’s just on the right side of acceptable, but its constant transferral of bumps could prove tiresome if you regularly traverse poor roads.

First, the M4 is one of the most sensitive cars to tyre temperature we’ve ever driven. On cold rubber at Haunted Hills (our chosen photography venue), early attempts to flick the car sideways for the camera result in severe understeer as the front tyres refuse to bite into the hotmix. Likewise, trail brake into a corner and the rear can step sideways like you’ve yanked on the handbrake.

However, let the rubber generate some heat and the experience transforms. Now the front-end has an almost unshakeable grip on the tarmac; at road speeds understeer simply doesn’t exist and on track you’d have to do something silly to get it to push wide, as usually it’s the rear end that lets go first.

This allows corners to be attacked with confidence while keeping in mind that, with DSC deactivated, the second part of the bend will be all about managing traction.

And DSC will need to be deactivated, because unfortunately M has completely dropped the ball in recalibrating the M4’s stability control. BMW boasted that drivers could practically spin the standard car in ‘M Dynamic mode’, but the Competition’s sports DSC setting is so frustratingly conservative that it cuts power dramatically at the slightest hint of wheelspin.

This means that to experience even a fraction of the M4 Competition’s ultimate potential drivers are forced to deactivate the electronic safety net, which is a difficult thing to recommend, as in slippery conditions it can be a right handful. Such is the amount of torque the 3.0-litre twin-turbo six produces that on a wet road it’ll easily wheelspin at speeds well in excess of the national speed limit.

Even in the dry the M4 has the power to light up its rear tyres with ease and catching it can require swift reactions. So we’re left with a conundrum: leave the overzealous safety net in place and accept that some of the M4’s excellence will remain untapped, or adopt a more cautious approach so as not to be caught out by unexpected conditions.

Unlike the BMW, the AMG’s electronics allow plenty of wheelspin and a reasonable degree of lateral movement, while still keeping a weather eye on proceedings. It’s an excellent setting for fast road driving, still requiring driver input to get the best out of the car but flattering any mistakes.

As you’d expect given the almost-200kg weight penalty, the C63 does feel heavier and less agile than the M4, however it counters with more communicative fixed-rate steering, greater predictability at the limit and smoother transitions to over and understeer should you exceed it.

Initially it makes the car feel edgy, like it’s falling into oversteer, but with ESP off it becomes clear there’s still plenty of traction available and it’s just straightening the car for corner exit, important when there’s 700Nm of torque on tap.

As you’d expect with this much grunt, the C63 will haze its rear tyres all day long, but it’s actually more rewarding a step back from this, using the throttle to help steer the car and exit corners in subtle drifts rather than tyre-smoking slides. It feels lighter than its claimed 1725kg and the optional carbon-ceramic front brakes are awesome.

They’re expensive at $9900, but Mercedes claims significantly decreased wear rates, so they’re worth considering for either car. At $15,000 on the M3/M4, they are a bigger investment, but you do get them at both ends as opposed to just the fronts on the C63.

The biggest question mark with the C63 Coupe is, is it too hardcore for its own good? Anyone in the market for a traditional fast, comfortable Mercedes coupe is likely to find the C63 too much, as Tobias Moers and his team have clearly been given carte blanche to build a monster.

The ride is very firm, though like the BMW just on the right side of acceptable in Comfort mode, but the removal of most of the rubber bushings from the rear end means the car feels extremely rigid.

At one stage, the glovebox flew open of its own accord when accelerating hard over a ridge in the road in third gear. To be honest both cars are similarly focused – NVH levels in the M4 aren’t great either – but it feels like a bigger shift in character for Mercedes than BMW.

The other trait the two cars share is a severe dislike of slippery conditions. Trying to drive the C63 even moderately enthusiastically in the wet is like watching a turtle struggling on its back; on one level it’s amusing, but ultimately an exercise in futility. There’s just way too much power to put through two tyres.

Its best effort was 0-100km/h in 4.56sec and a 12.48sec quarter mile at 194.10km/h; still extremely fast, but there are another three or four tenths in it on a grippier surface.

Nevertheless, the engine utterly dominates the C63. No matter the gear or rpm there’s always a relentless torrent of torque available and it sounds like a grizzly bear with a bad head cold. Unfortunately, the transmission remains an AMG weak point.

With its inability to ‘creep’, the BMW’s seven-speed dual-clutch isn’t great at low-speed manoeuvring either – three-point turns are a right pain – but it is better behaved than the Merc and manual shifts via the paddles are answered more obediently. Its biggest downfall is the unnecessary and irritating jolt on upshifts, which are not only uncomfortable but can lead to a loss of traction in the next gear.

Some pundits have labelled the M4’s 3.0-litre twin-turbo six dull, which seems extremely harsh for an engine that hits this hard in the mid-range yet revs well beyond 7000rpm. While hailed for its response when it first appeared, compared to the very latest turbo engines there is some low-down delay, but that only makes the boost feel even more exciting when it does arrive.

In what must qualify as a minor miracle, the notoriously capricious launch control actually worked and hurled the M4 to 100km/h in 4.39sec and across the quarter in 12.38sec at 193.31km/h. While we matched the time doing it the old fashioned way, the electronics were more consistent.

Where the BMW loses ground to the Mercedes is in character. The M4 Competition does sound fruitier than the standard car, but the S55 engine needs the M Performance exhaust (a $9350 option) to really gain some personality.

And it’s in this highly subjective area that the M4 Competition loses this comparison. In its favoured operating range – going as fast as possible with maximum commitment – the BMW is incredible, an adrenalin-pumping experience that leaves your eyes on stalks and your nerves abuzz.

And on a purely objective basis, you could even make a case for the M4 winning, as it’s every bit as quick as the C63, faster around a track, slightly roomier inside and, as-tested, more than $15,000 cheaper.

All too often that’s an intangible quality, but thankfully here it can be easily quantified: it’s the noise of that twin-turbo V8 on start-up, its low-speed rumble around town and the feeling of limitless power. Only a small detail, but an important one.