THERE appears to be no place for reasoned argument in the development of the Alfa Romeo SZ. How could there be? It was a vanity project which, like most such ventures, rapidly imploded into a morass of debt and recrimination.

The back story, however, began with gimlet-eyed opportunism. In the late-1980s, a boom in the prices of supercars saw many delivery-mileage Ferraris, Lamborghinis and Porsches being flipped on dealer forecourts for double the list price. This was clearly an unsustainable bubble, but Alfa saw it as a window in which to revive its fortunes, develop a headline-grabbing halo model and, at the same time, revive links with the Zagato styling house.

While the styling is the aspect of the SZ that most identify with – for better or worse – the car’s role as a mobile laboratory saw it pioneer a number of technological firsts for Alfa.

Two rival styling teams were commissioned to work on the coupe in February 1987, overseen by Zagato, who would build the car. Walter De Silva and Alberto Bertelli’s team from Alfa Centro Stile, went head to head with a design team led by Fiat Centro Stile’s Mario Maioli, overseen by Robert Opron; the two concepts dubbed Project A and B respectively. Project A emerged as a more conventional, cab-back coupe with a low nose and a sharply chopped rear, reminiscent of the 1969 Zagato Junior GT. It was pretty but otherwise conventional, reminiscent of the 1983 Matra Murena in its key proportioning.

The same couldn’t be said of Project B’s work. It looked like nothing ever built, brutalist and heavyset, with a floating turret of glasshouse perched atop a cleaved red wedge. On 31 July, 1987, Project B got the nod and just 19 months later, the ES30 show car’s six Carello lamps were eyeballing a befuddled press corps at the 1989 Geneva Show.

While much was made of the fact that it sat on the same chassis with an identical wheelbase to the Alfa 75, the SZ’s build was nevertheless radical. Planning times were reduced by the use of CAD/CAM – a first for Alfa – with the CAD model indicating that roof height needed to be increased by 35mm. The CAD data flowed into computational aerodynamics, developing basic panel forms that cleaved the air cleanly.

Every panel was supplied with data on spot pressures and boundary layers between laminar and turbulent flows at a variety of speeds before the car ever entered the wind tunnel at Orbassano. The only changes revealed in tunnel testing were tweaking the upper edge of the bonnet and smoothing areas around the headlamps. The steel chassis was clothed in Modar (a thermoset metacrylic resin), with carbonfibre used for parts like the rear wing and aluminium for the roof panel.

The production car was readied by the end of the year and hustled onto dealer floors carrying a price tag – in Europe – around that of a Porsche 911. Unfortunately it arrived just as the exotic-car feeding frenzy turned into a famine. Although Alfa reckoned the technique of bonding the Modar resin onto the steel frame using the adhesives as a structural component could support a build rate of 10,000 cars per year, little over 1000 SZs ever left Zagato’s premises in Terrazzano di Rho. Its drop-top sibling, the 1992 RZ, is an even rarer sight, with only 278 cars of a predicted 350-unit production run being built.

On a purely commercial basis, the RZ/SZ project was an abject failure. What’s more, it failed to kick-start Zagato’s fortunes, while a gun-shy Alfa Romeo would take another 14 years before revisiting the idea of the halo sports model in the voluptuous shape of the 8C Competizione. This failure to hit too many of its pre-development targets, coupled with the fact that the styling – for a while at least – dated very badly, meant the SZ appeared surgically excised from Alfa’s history for a while.

The shape is something that never rests easily on the eye, 30 years having done little to mellow its impact. The arachnoid eyes, crazy planes, vertiginous haunches and stunted glasshouse have never become a design lingua franca and the panel gaps are so wide that you could probably check the oil without popping the bonnet.

Drop inside and our example is all buttery tan leather, with a dashboard angled towards the driver and fantastic visibility, courtesy of that show-car glasshouse and filament-thin arching pillars. Headroom is a little pinched for taller drivers and the driving position takes a bit of lateral thinking to get comfortable with.

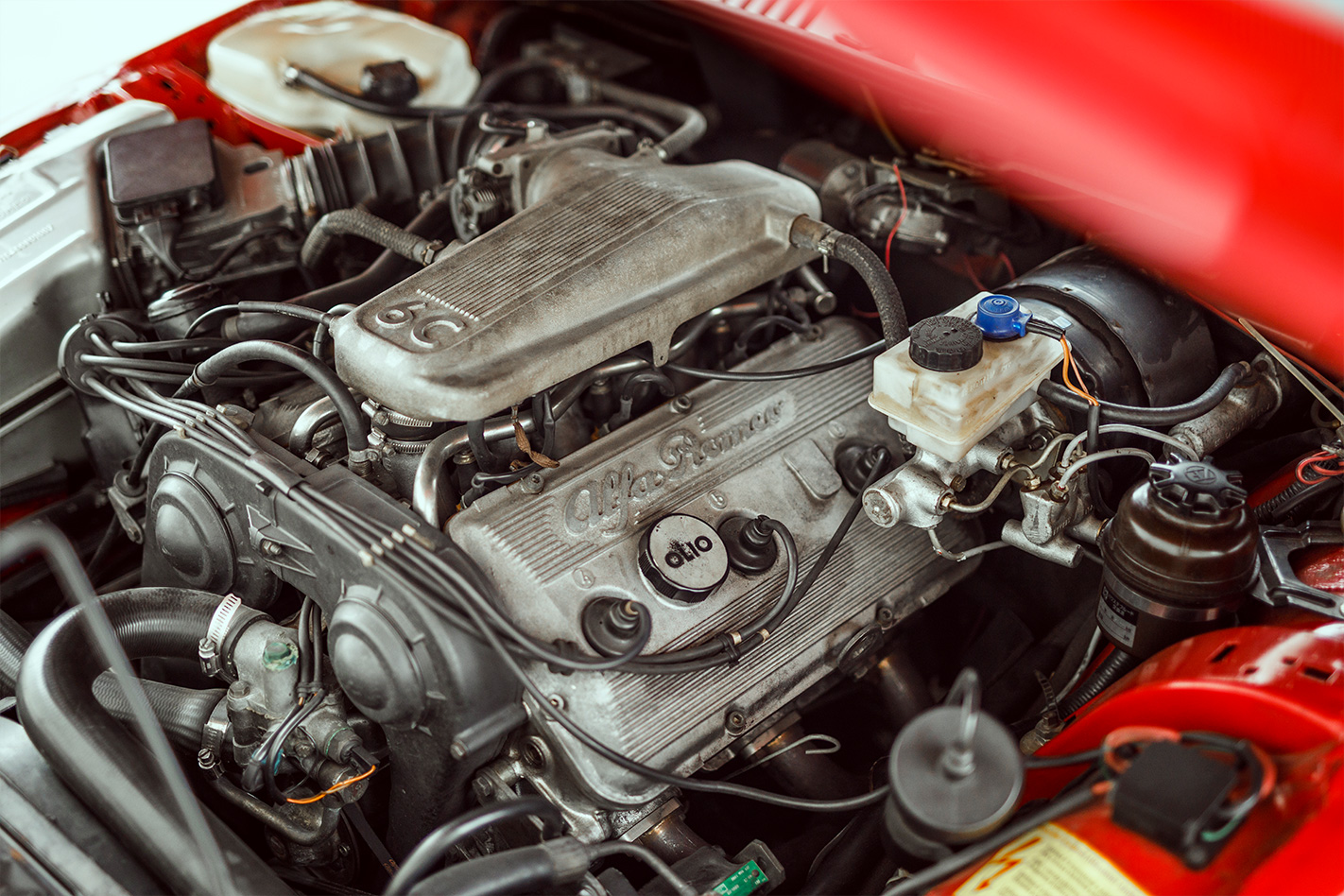

Key the ignition and the car fires on the first attempt, settling back into a tappety thrum. The gear-change action isn’t at all bad for a car with its long-throw ‘box such a long way rear of the stick, although you can’t rush the synchro: one-pause-two between gears. The Busso 3.0-litre V6 makes 152kW, differing from the 75’s installation with uprated intake and exhaust manifolds, tweaks to the cooling system and Bosch Motronic ML4.1 electronics. Despite Alfa having a 24-valve version of this engine in advanced stages of development, time was against the SZ and it got the existing 12-valve architecture instead.

It’s still one of the great charismatic engines, pulling sharply from as little as 2000rpm right up to its power peak at 6200rpm, the exhaust note hardening as it comes on cam from 4000rpm.

By today’s standards, the SZ wouldn’t even rate as brisk, registering a 0-100km/h time of seven seconds and a top end of 245km/h, but the design ethos for the car was to create a vehicle that was modern in execution but classic in feel, and Alfa nailed that particular assignment.

Chassis development was the responsibility of Giorgio Pianta, the former rally driver who had fettled Lancia’s competition cars for the likes of Markku Alen, Henri Toivonen and Walter Rohrl, and his imprimatur is all over the SZ. He junked the torsion beam of the 75 in favour of Koni coaxial springs and dampers, the de Dion rear axle handling camber changes.

The chassis is stiffened, shock absorber mounting points beefed up and the suspension tuned to the sidewall stiffness of the then-revolutionary Pirelli P Zero tyre. The car has a long-legged suppleness to its suspension that matches the low-end torque response of the engine.

Drive it gently and it doesn’t feel like a sports car at all, but scruff the car a little and it responds in kind with great body control into corners and tenacious turn-in, courtesy of a trademark Pianta front end: aggressive negative camber and zero aerodynamic lift.

This isn’t a high-tech car. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. Alfa deliberately rejected all-wheel drive, four-wheel steering, traction control and even anti-lock brakes in the SZ’s development, delivering a contrarily analogue driving experience. The only overtly modernist feature is the electrical ride-height control. In order to quell lift, the SZ sports a ride height more usually associated with snowploughs, which would doubtless prove interesting on a typically lumpen Aussie country road, but press a button in the cabin and the car elevates by 50mm.

It’s hard to fault the hydraulically assisted steering but the brakes are truly abysmal, with a heart-in-mouth dead feel for a huge arc of pedal travel. Attempt a heel-and-toe downchange and it turns into a kind of desperate heel-and-shin contortion before you give up. All SZs suffer the same delinquent brake feel. Punch them to the threshold of locking and they work well enough, slowing from 100km/h in a respectable 38 metres, but it feels like a clumsy, brutish interaction that jars with the measured tactility of the rest of the car’s controls. Pianta claimed the SZ was 10 seconds quicker around Balocco than a 3.0-litre 75, with only 1.5 of those seconds made on straights, the rest a combination of better suspension, some modest ground effect and the benefits of the P-Zero tyre.

Before driving the car, I wondered if the SZ was a bit of a cynical charade; a 75 in a fright wig that only appealed to some due to its divisive styling. Spend a little time with one and it becomes apparent that you’ll love it for the very specific way it drives, and that the aesthetics will become a secondary concern.

While there is some truth in its description by motoring scribe Russell Bulgin as ‘a fairly creative stroll through the Alfa parts warehouse’, the SZ has no issue with its own identity. Although you can detect some Alfa 75 flavour in the way the SZ comports itself, it’s only a faint tang. Stiffer, lower and more potent, the coupe stands alone as a great Alfa driver’s car in a period where such vehicles were notable by their absence.

There’s a sensuality to the SZ that its brutalist architecture does a great deal to mask. If nothing else, time spent with the SZ demonstrates a simple truth. When you catch a glimpse of greatness, be ready to pause and take it in. After all, you never quite know when you might find beauty in unexpected places.